Vulvar and Vaginal Cancer

Natalie S. Gould

Joan L. Walker

Vulvar and vaginal cancer represent uncommon gynecologic cancers that occur most often in older women. Squamous lesions are the most frequent histology, and risk factors are similar for both disease sites. This chapter describes the epidemiology, clinical presentation, patterns of spread, and treatment of squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva and vagina. Less common histologic subtypes, including Paget’s disease, melanoma, adenocarcinomas, and sarcomas, are also reviewed.

Vulvar Carcinoma In Situ

Vulvar carcinoma theoretically results from malignant transformation of a vulvar carcinoma in situ as is seen with cervical squamous lesions. Unlike squamous lesions of the cervix, the natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is less well understood. The incidence of vulvar dysplasia has increased over the last 20 years, particularly among younger women. A report from Austria demonstrated a 307% increase in the overall incidence of high-grade VIN and a 394% increase among women younger than 50 years of age between 1985 and 1998. In a review of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, Judson found that the incidence of VIN III increased 411% from 1973 to 2000 from 0.56 cases per 100, 000 to 2.86 per 100, 000. This increase in incidence occurred predominantly in women younger than 65 years with a peak incidence from 40 to 49 years. Jones recently reviewed 405 cases of VIN2–3 treated between 1962 and 2003 in New Zealand. The mean age at diagnosis decreased from 50 to 39. Factors implicated in the increase in dysplasia include increased human papillomavirus (HPV) infection; tobacco use; immunosuppression either with HIV, organ transplant, or diabetes; and increased surveillance.

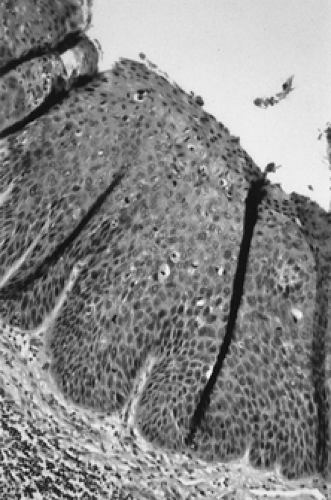

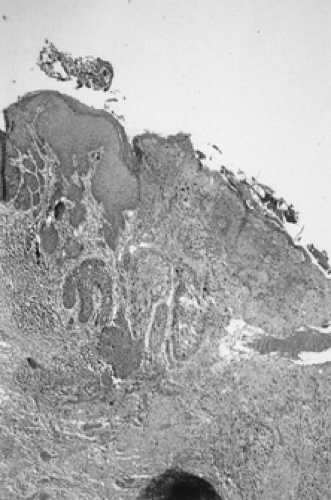

Patients with VIN most commonly present with pruritus and vulvar lesions. These lesions may appear scaly, white, red, or hyperpigmented (Figs. 57.1, 57.2). Careful inspection with 5% acetic acid and liberal use of punch biopsy are the cornerstones of diagnosis (Fig. 57.3). An underlying malignancy may be present in 3.2% to 22.0% of patients who undergo surgical excision for vulvar carcinoma in situ. Wide local excision with at least a 5-mm margin is the preferred management option, as it allows pathologic confirmation and is associated with less morbidity than skinning vulvectomy. Skinning vulvectomy with split-thickness skin graft may be an option in patients with widespread disease. Small series, which are hindered by short clinical follow-up, demonstrate regression of VIN with use of 5% imiquimod cream. Carbon dioxide laser ablation or ablation with the Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA) is also an effective option for patients with multifocal or clitoral disease with a better cosmetic outcome. Recurrences are frequent (10% to 50%) despite surgical technique used or the presence of negative surgical margins. Untreated VIN3 has a risk of progression to invasive cancer of 2% to 9%. Therapy should be tailored to symptom control and ruling out underlying malignancy. Patients should be followed every few months with careful visual inspection of the vulva and be taught self-exam skills as well.

Epidemiology

Vulvar carcinoma is the fourth most common genital tract malignancy in women, representing 3% to 5% of gynecologic malignancies with an estimated 3,740 cases and 880 deaths per year in the United States in 2006. The majority of cancers are squamous in origin, with occasional cases

of basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, and Paget’s disease.

of basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, and Paget’s disease.

Figure 57.1 Vulvar carcinoma in situ presenting as a white or hyperpigmented lesion. (See Color Plate) |

Vulvar cancer tends to be a disease of older women, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 65 years. As the population ages, more older women will be at risk for vulvar carcinoma. Despite a dramatic increase in the incidence of VIN3 seen from 1973 to 2000, Judson found only a 20% increase in invasive vulvar cancer over that time. Evidence exists that there are two distinct types of vulvar carcinoma with different etiologies. Tumors in older women are often unifocal and may be associated with chronic vulvar inflammation of long-standing duration such as lichen sclerosus or hyperplastic dystrophy. These keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas have associated HPV changes in only 6% of cases. While retrospective studies indicate that up to 50% of vulvar carcinomas are related to hyperplastic dystrophies and lichen sclerosus, prospective studies have demonstrated that only 5% of women with vulvar dystrophies develop invasive carcinoma. Cancers found in younger women tend to be multifocal with adjacent VIN and have a basaloid or warty histology. Nearly 90% are associated with HPV infection, particularly HPV 16. Of women with HPV-associated lesions in a series by Trimble and colleagues, 38% were under age 55 compared with only 17% of those with classic keratinizing squamous cancers. Other associated risk factors include immunosuppression from chronic steroid use, organ transplant, diabetes or HIV, smoking, and a history of other lower genital tract dysplasia or neoplasia.

Presentation

Most women present with pruritus, burning, or bleeding in the presence of an identifiable lesion (Figs. 57.4, 57.5).

Unfortunately, there is often a delay of many months or even years between onset of symptoms and diagnosis. This is in part because patients self-medicate with a variety of over-the-counter preparations rather than seek care and also because physicians may not biopsy liberally. The cornerstone for diagnosis of vulvar malignancy is a low threshold for an office biopsy, as it may be extremely difficult to distinguish clinically between dysplasia, chronic vulvar dystrophy, and carcinoma (Fig. 57.6). Any patient with symptoms lasting for longer than 2 weeks deserves a thorough exam and a biopsy. In order to adequately evaluate a patient with a vulvar lesion, 5% acetic acid is applied to the vulva for 5 minutes and then the area is examined either with the naked eye or a handheld magnifying glass. The entire vulva, including the hair-bearing, perianal, and periclitoral regions, should be examined for suspicious ulcerations and hyperpigmented, acetowhite, or gross warty lesions. Up to 5% of patients will have multifocal disease and may require multiple 5-mm punch biopsies.

Unfortunately, there is often a delay of many months or even years between onset of symptoms and diagnosis. This is in part because patients self-medicate with a variety of over-the-counter preparations rather than seek care and also because physicians may not biopsy liberally. The cornerstone for diagnosis of vulvar malignancy is a low threshold for an office biopsy, as it may be extremely difficult to distinguish clinically between dysplasia, chronic vulvar dystrophy, and carcinoma (Fig. 57.6). Any patient with symptoms lasting for longer than 2 weeks deserves a thorough exam and a biopsy. In order to adequately evaluate a patient with a vulvar lesion, 5% acetic acid is applied to the vulva for 5 minutes and then the area is examined either with the naked eye or a handheld magnifying glass. The entire vulva, including the hair-bearing, perianal, and periclitoral regions, should be examined for suspicious ulcerations and hyperpigmented, acetowhite, or gross warty lesions. Up to 5% of patients will have multifocal disease and may require multiple 5-mm punch biopsies.

Staging/Spread Patterns

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) surgical classification system replaced clinical staging for vulvar cancer in 1989 (Table 57.1). By relying on histopathologic classification of the lymph nodes, the new system more accurately reflects prognosis since the previous system provided an inaccurate assessment of inguinal femoral lymph node involvement in one fourth of cases.

TABLE 57.1 Vulvar Carcinoma: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Staging 1994 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Local spread occurs to contiguous structures such as the vagina, urethra, and rectum. Metastatic spread via lymphatics is common and has been well characterized by anatomic studies. Lateralized lesions tend to be characterized by spread to the ipsilateral inguinal nodes first, followed by contralateral inguinal nodes, and then pelvic nodes. Midline lesions, or those approaching 1 cm from the midline, may have lymphatic drainage to both inguinal regions. Metastasis to the contralateral groin or pelvic nodes is rare in the absence of ipsilateral groin node involvement. The superficial inguinal nodes above the cribriform fascia are believed to be involved prior to the deep femoral nodes below the cribriform fascia. Risk of lymphatic spread is related to tumor size, tumor thickness, older patient age, tumor grade, presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and clinically suspicious groin nodes. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) found groin node metastasis in 19% of patients with lesions ≤2 cm and in 42% of patients with lesions >2 cm. The GOG surgicopathologic staging analysis also demonstrated that lymph node dissection could be safely omitted in patients with <1 mm of stromal invasion. Hematogenous metastasis to distant organs such as bone, liver, and lungs is rare as a primary event but may be seen in patients with recurrent disease.

Treatment

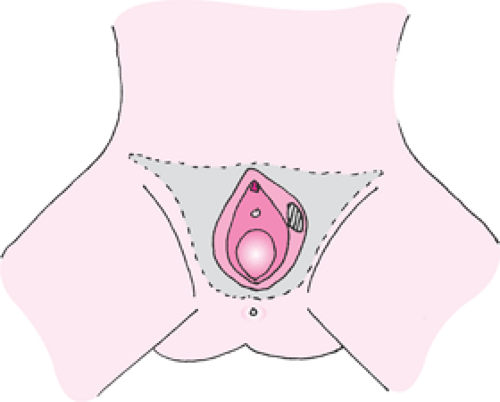

Historically, vulvar cancer has been treated with en-bloc radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy or “longhorn incision” (Figs. 57.7, 57.8). This technique resulted in significantly improved survival, but the morbidity was extensive with a median hospitalization of 30 days, 70% to 90% wound breakdown, and chronic debilitating lymphedema in nearly 9% of women. Significant disruption in self-image and sexual function also occurred. Attempts to decrease morbidity first led to the use of separate incisions for groin node dissection while continuing to use radical vulvectomy. In 1981, Hacker and colleagues reported a series of 100 patients who underwent radical vulvectomy and lymphadenectomy through three separate incisions. The incidence of major wound breakdown was only 14%, with a mean hospitalization shortened to 19 days. This procedure lead to the shortest length of hospitalization reported at that time and produced a dramatic decrease in complications. The majority of local recurrences were salvaged with repeat excision. Overall survival was not compromised by deviating from en-bloc dissection, and the authors concluded that this technique is appropriate for patients with stages I and II vulvar carcinoma.

Figure 57.7 A longhorn incision. Radical excision of the vulva from genitocrural fold to genitocrural fold, deep to the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm along with en-bloc lymphadenectomy. |

Figure 57.8 Surgical specimen after en-bloc radical vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy via longhorn incision. |

DiSaia and associates first proposed conservative vulvar surgery in 1979 as a way of preserving sexual function in young patients. Requirements for conservative surgery were an invasive cancer ≤1 cm in diameter confined to the vulva with <5-mm depth of invasion. Patients were treated with radical wide excision ensuring a 3-cm margin, and lymphadenectomy was performed through separate groin incisions. There were no recurrences at a mean follow-up of 32 months, and sexual function was deemed preserved. The authors concluded that there existed a subset of patients with vulvar cancer who could be treated with less radical vulvar procedures.

Berman and coworkers expanded the experience with conservative surgery in 1989 with a report of 50 patients with T1 lesions treated with radical local excision, again providing a 3-cm margin and superficial lymphadenectomy. No patient had a resection margin positive for carcinoma. Median hospital stay was shortened to 7 days, and only 12% required wound debridement compared with 50% or more with historical controls. There were five recurrences (10%), four of them local. All local recurrences were salvaged with a second local resection.

In 1990, Burke and colleagues provided the first report of a conservative vulvar surgery in patients with both T1 and T2 lesions. Thirty-two patients (15 with T2 lesions) underwent radical wide excision, removing a 1- to 2-cm margin of normal tissue in addition to selective inguinal

dissection. The mean lesion diameter was 23.0 mm with a mean depth of invasion of 4.1 mm. No patients had invasive cancer at the surgical margins, but 19% were positive for VIN. The authors reported only 15.5% wound separation, with a mean hospital stay of 10 days. Three patients (10%) developed local recurrence, and two were salvaged with repeat excision. The authors concluded that radical wide excision appears to be an acceptable surgical option for patients with resectable vulvar carcinomas.

dissection. The mean lesion diameter was 23.0 mm with a mean depth of invasion of 4.1 mm. No patients had invasive cancer at the surgical margins, but 19% were positive for VIN. The authors reported only 15.5% wound separation, with a mean hospital stay of 10 days. Three patients (10%) developed local recurrence, and two were salvaged with repeat excision. The authors concluded that radical wide excision appears to be an acceptable surgical option for patients with resectable vulvar carcinomas.

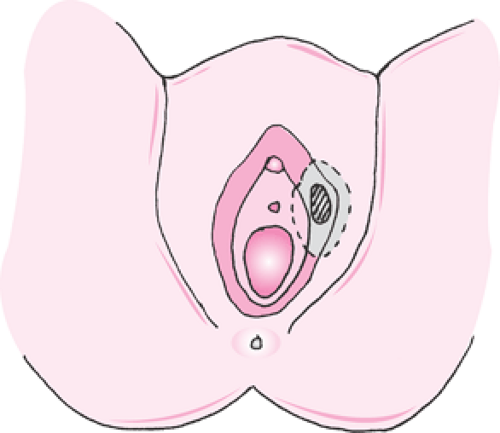

As these retrospective trials used differing criteria to identify patients suitable for less radical approaches, the GOG conducted a prospective trial beginning in 1983 that evaluated modified radical hemivulvectomy and ipsilateral superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy in 155 patients with clinical stage I vulva carcinoma limited to a depth of invasion of <5 mm. A 2-cm margin of normal skin around the lesion was excised. There were 19 recurrences and 7 deaths among 122 patients available for evaluation. Recurrences were evenly distributed between local and distant failures. Acute and long-term morbidity was decreased significantly compared with that found in historical controls but at the cost of increased risk of local recurrence. The authors concluded that although there was no consensus regarding the characteristics that would make a patient with early vulvar carcinoma a candidate for a limited surgical approach, this approach appeared to be an alternative to traditional radical surgery for a highly selected group of patients with stage I vulvar carcinoma (Figs. 57.9, 57.10).

A need for establishing a clear margin for treatment of patients with vulvar cancer may be more important than the particular treatments. Heaps and colleagues reviewed surgicopathologic factors predictive of local recurrence in 135 patients treated with radical vulvectomy or radical local excision. Twenty-one developed local recurrence after radical resection. No patient with a surgical tumor-free margin ≥8 mm suffered from local recurrence but 48% with <8-mm margin recurred locally. As an 8-mm margin on fixed tissue corresponds to 10-mm margin with fresh tissue, the authors concluded that use of a 1-cm margin should successfully prevent local recurrence and reduce the currently used standard margin by over 50%. This would allow further modification of the procedure in order to decrease morbidity and avoid disfigurement and loss of organ function without sacrificing survival.

Figure 57.9 Modified radical vulvectomy. Radical excision of the vulva deep to the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm with a 2-cm margin around the lesion. |

Figure 57.10 Surgical specimen after modified radical vulvectomy. Lymphadenectomy is performed through separate incisions. |

Other modifications in the surgical management of vulvar carcinoma over the last 30 years include the elimination of routine pelvic lymphadenectomy and elimination of contralateral groin node dissection in patients with lateral T1 lesions and negative ipsilateral nodes.

Overall survival in vulvar carcinoma is related to groin node status and lesion diameter with nodal status being the most important factor. Five-year survival is 98% for patients with negative nodes and a T1 lesion. Patients with one to two positive ipsilateral nodes have over 70% to 80% 5-year survival, while those with three or more positive nodes or bilaterally positive nodes have survival in the range of 12% to 36% (Table 57.2). Postoperative adjuvant groin radiotherapy is indicated in patients with more than one positive node or clinically evident groin nodes.

TABLE 57.2 Survival by Groin Node Status and Lesion Size in Vulvar Carcinoma |

|---|