Ovarian and Tubal Cancers

Ilana Cass

Beth Y. Karlan

Abnormalities of the ovary or fallopian tube may result from physiologic changes, infectious processes, or benign or malignant neoplasms. Patients may exhibit a pelvic mass with or without other signs or symptoms. These disorders may occur at any age from childhood to senescence. Depending on patient age, physiologic and pathologic manifestations and implications may vary. For example, teenage patients with a pelvic mass most likely will have a benign germ cell or epithelial ovarian tumor, whereas postmenopausal women have a significantly greater risk of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. The differential diagnosis and the radiologic and tumor marker workup will vary, depending on patient age and initial complaints. The clinician must be vigilant and willing to evaluate the vague symptoms that are frequently the hallmark of many ovarian and tubal pathologies, especially in women over the age of 40.

In recent years, we have gained an increased understanding of ovarian and tubal tumor biology and the underlying molecular genetics, but these advances can be translated only slowly to the clinic. This chapter will outline ovarian and fallopian tube neoplasms, including the common epithelial histologies as well as rarer germ cell and stromal tumors. Epidemiology and risk factors for these cancers, including inherited cancer susceptibility due to mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) will be discussed as well as preventative and screening strategies.

Germ Cell Tumors

Germ cell tumors occur most frequently in young women and girls and account for 90% of prepubertal tumors and 60% of tumors in women younger than 20 years. These tumors arise from the germ cells originating in the embryonic yolk sac. Patients usually present with complaints of abdominal pain and have an associated pelvic or abdominal mass. Others might present with acute abdominal pain as a result of ovarian rupture, hemorrhage, or torsion. A misdiagnosis of acute appendicitis has been made in these circumstances.

Mature Cystic Teratoma

Mature cystic teratomas, also known as dermoid cysts, are the most common benign ovarian neoplasm, with a peak incidence from ages 20 to 40 years. However, they can also be seen in infancy as well as in menopausal woman. Mature cystic teratomas originate from primordial germ cells and are composed of well-differentiated derivatives of any combination of the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Ectodermal elements usually predominate. Although they are in general benign, on rare occasion they may undergo malignant transformation in one of the elements, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most frequent malignant histology.

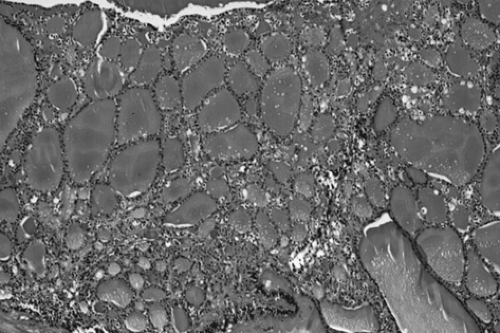

Grossly, the tumors are round or oval with a smooth, glistening, gray-white surface. The majority of tumors measure 5 to 10 cm in diameter, with 8% to 15% of cases being bilateral. The tumors are usually unilocular but occasionally multilocular and are filled with hair and a fatty material similar to sebum. A solid portion located at one pole of the cyst and projecting into the cavity is known as a Rokitansky protuberance, where all three germ cell layers are found. (Fig. 61.1). Tissues also can be found at the protuberance, such as hair, teeth, bone, glia, neural tissue, cartilage, retina, smooth muscle, fibrous and fatty tissue, gastrointestinal and bronchial mucosa, and thyroid and salivary gland

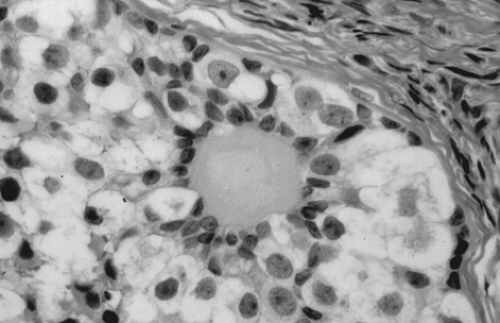

tissue. Microscopically, ovarian stroma is noted on the outside wall, with the cyst being lined by mostly squamous cell epithelium with underlying sebaceous and sweat glands (Fig. 61.2).

tissue. Microscopically, ovarian stroma is noted on the outside wall, with the cyst being lined by mostly squamous cell epithelium with underlying sebaceous and sweat glands (Fig. 61.2).

In the past, a diagnosis of benign cystic teratoma was usually made on an abdominal radiograph in a young woman with acute abdominal pain, because osseous differentiation or teeth could be seen in the pelvis. Transvaginal sonography, however, has become the diagnostic test of choice in most centers, although pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain and may be especially useful when the mass is detected during pregnancy. Torsion is a frequent complication, because these tumors are relatively buoyant and mobile. Treatment usually involves ovarian cystectomy, with preservation of normal ovarian tissue and close inspection of the contralateral ovary. This often can be accomplished laparoscopically, when the dermoid cyst can be shelled out from the remaining normal ovary. Although concern for chemical peritonitis resulting from cyst rupture exists, with copious irrigation of the peritoneal cavity, this complication can be avoided.

Figure 61.2 Mature cystic teratoma. Microscopically, there is a keratinizing squamous epithelium on the right and mature glial tissue on the left. |

Struma Ovarii and Strumal Carcinoid

Rarely, ovarian teratomas will contain a single specialized tissue type. Struma ovarii is a subset of mature cystic teratomas in which the tumor is composed entirely or predominantly of thyroid tissue. Grossly, the cut surface shows gelatinous red to green-brown colloid, and microscopically mature thyroid tissue is seen (Fig. 61.3). Struma ovarii accounts for <3% of mature teratomas, with similar age distribution and similar clinical findings. However, thyroid gland enlargement is occasionally seen, and about 5% of patients with struma ovarii will experience signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Malignant changes in a struma ovarii are rare but can occur and are most frequently of a follicular histology (unlike primary thyroid carcinomas). Approximately 30% of reported cases of malignant struma ovarii are associated with metastasic disease. Evaluation with iodine-131 scanning may be helpful, and treatment is often similar to that given for thyroid carcinoma counterparts.

Strumal carcinoids are rare teratomas characterized by a mixture of thyroid and trabecular carcinoid tissues. Primary carcinoid tumors of the ovary account for <5% of ovarian teratomas and most likely arise from argentaffin cells found in the gastrointestinal or bronchial tissues that make up the teratoma. These tumors often are hormonally active due to the secretion of serotonin, bradykinin, and other peptide hormones that are secreted directly into the systemic circulation and are not inactivated by “first pass” through the liver. Approximately 50% of ovarian carcinonoids >4 cm in diameter will be associated with carcinoid syndrome, including episodic cutaneous flushing, diarrhea, and bronchospasm.

Malignant Germ Cell Neoplasms

Malignant ovarian germ cell tumors account for <5% of all ovarian cancers. Table 61.1 provides a listing of the World Health Organization classification of germ cell tumors of the ovary. Their male counterpart, testicular cancer, is approximately ten times more common than ovarian germ cell tumors, and many of the chemotherapy regimens that are used have been adapted from clinical trials in patients with the corresponding type of testicular cancer.

These interesting tumors tend to be diagnosed at an earlier stage than the common epithelial ovarian carcinomas, and they are very sensitive to chemotherapy and, in the case of dysgerminoma, to radiotherapy as well. Germ cell tumors have distinct histopathologic features and tumor markers that are useful in diagnosis and follow-up. Table 61.2 outlines the serum markers typically associated with germ cell tumors.

TABLE 61.1 World Health Organization Classification of Germ Cell Tumors | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Dysgerminoma

Dysgerminoma accounts for 33% of all malignant germ cell tumors, with a trend toward a decreasing incidence according to large population-based registries. Approximately 50% of the patients with this tumor are younger than 20 years and 80% are younger than 30 years, with a peak incidence among 15 to 19 year olds. Children with dysgerminoma may present with precocious puberty or primary amenorrhea. The serum lactate dehydrogenase level is almost always elevated and serves as a tumor marker during treatment and follow-up.

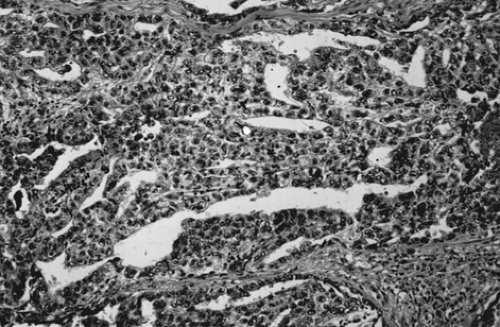

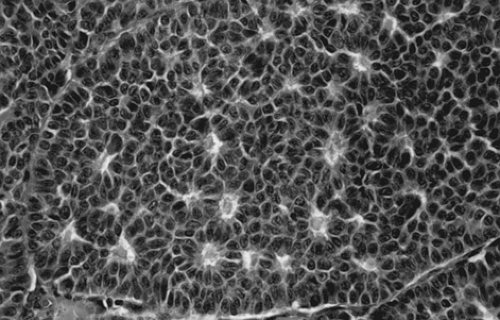

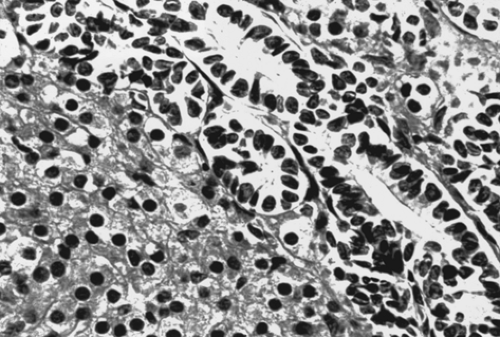

Although dysgerminoma tends to be unilateral, approximately 10% to 15% of tumors are bilateral. They usually are gray-white, smooth, and fleshy in appearance and on cut surface usually are solid. Hemorrhage and necrosis may be seen. Cystic areas suggest the presence of mixed germ cell elements that would require further careful sampling of the specimen. The microscopic appearance of an ovarian dysgerminoma is similar in histology to its male counterpart, testicular seminoma, with aggregates of tumor cells surrounded by connective tissue stroma containing many lymphocytes and foreign body giant cells. (Fig. 61.4). Mitotic activity is almost always present. In fewer than 10% of patients, syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells may be detected, producing human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) that may be demonstrated in tissue section by immunohistochemical techniques and in the serum by an elevated hCG level. Syncytiotrophoblastic cells in a dysgerminoma do not have prognostic significance; however, serum β-hCG levels can be used to monitor patient response to treatment and in follow-up.

TABLE 61.2 Tumor Markers Associated with Germ Cell Neoplasms: Likelihood of Elevation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Treatment is determined by patient age. Because most patients are of reproductive age, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and a full staging procedure with preservation of the contralateral ovary and the uterus are recommended as long as there is no evidence of disease in the contralateral ovary. Table 61.3 is a listing of procedures required when a full staging procedure is performed. Table 61.4 illustrates the widely used International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system for all ovarian cancers. Observational studies have revealed identical remission rates for conservative treatment (e.g., unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging) and complete extirpative therapy (e.g., bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with a hysterectomy) in early-stage disease. Routine biopsy of the contralateral ovary should be avoided if it appears normal. If gross tumor is noted in both ovaries, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy of the larger ovary, a unilateral cystectomy, and a full staging procedure followed by chemotherapy may be appropriate in those patients who desire to retain fertility. Patients with advanced disease may require complete removal of the reproductive organs, which should be performed in consultation with a gynecologic oncologist.

Figure 61.4 Dysgerminoma. Loose aggregates of tumor cells are separated by connective tissue that contains abundant lymphocytes. |

Dysgerminoma is very sensitive to both radiation and chemotherapy. Since it is a disease of young women, chemotherapy is the most appropriate postoperative treatment in these patients and should be offered to those with disease more advanced than stage Ia. Combination therapy with (a) vincristine sulfate (Oncovin), dactinomycin (Cosmegen), and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (VAC) or (b) vinblastine sulfate (Velban), bleomycin sulfate (Blenoxane), and cisplatin (Platinol) (VBP) has been used with excellent results, especially in stage I patients. The combination of bleomycin, etoposide (VP-16), and cisplatin (BEP) has been found to be even more effective in treating all stages of disease, with a sustained remission in essentially 100% of patients. The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) have used BEP in their treatment of dysgerminoma in all stages of disease and have reported prolonged diseasefree interval with three to six cycles of therapy, depending on disease status, residual disease, and tumor markers. In an effort to explore

regimens with lower toxicity, the GOG reported a regimen of carboplatin and etoposide for completely staged and resected stage Ib-III patients with dysgerminomas. Despite favorable results, BEP remains the recommended first-line therapy based on descriptive studies (type III evidence). In patients with pure dysgerminoma seemingly confined to the ovary who were inadequately staged, administration of three cycles of adjuvant BEP is recommended due to a recurrence rate of 20%. However, the scientific merit of this treatment plan requires further investigation. Another option is to offer a repeat surgery to fully stage the disease. There have been several reports of secondary neoplasm, especially hematologic malignancies, after the use of BEP and other etoposide-based regimens. Although these are rare occurrences, careful long-term follow-up and evaluation of the risk–benefit ratio may be warranted to assess the efficacy of this regimen with and without etoposide.

regimens with lower toxicity, the GOG reported a regimen of carboplatin and etoposide for completely staged and resected stage Ib-III patients with dysgerminomas. Despite favorable results, BEP remains the recommended first-line therapy based on descriptive studies (type III evidence). In patients with pure dysgerminoma seemingly confined to the ovary who were inadequately staged, administration of three cycles of adjuvant BEP is recommended due to a recurrence rate of 20%. However, the scientific merit of this treatment plan requires further investigation. Another option is to offer a repeat surgery to fully stage the disease. There have been several reports of secondary neoplasm, especially hematologic malignancies, after the use of BEP and other etoposide-based regimens. Although these are rare occurrences, careful long-term follow-up and evaluation of the risk–benefit ratio may be warranted to assess the efficacy of this regimen with and without etoposide.

TABLE 61.3 Complete Staging Procedure for Ovarian Malignancy | ||

|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 61.4 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Staging for Ovarian Cancer. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Immature Cystic Teratoma

Like mature cystic teratoma, immature cystic teratoma is composed of tissues derived from all three germinal layers, except that they also contain embryonic tissue. This group of tumors is the most common malignant germ cell tumor, representing about 36% of all such tumors. Unlike mature cystic teratoma, which occurs in all ages but more frequently in the reproductive years, immature cystic teratoma is essentially found in the first 3 decades of life. It usually grows rapidly through its capsule, forming adhesions to the surrounding structures, and implants in the peritoneal cavity.

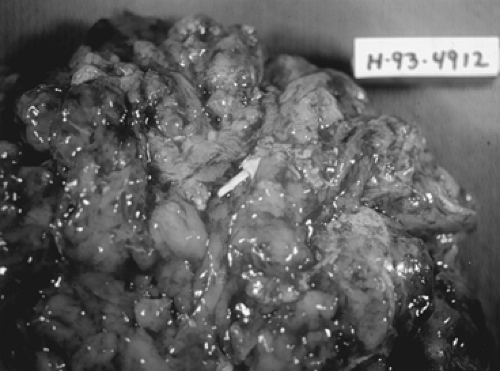

Tumors are usually smooth and unilateral, ranging from 9 to 28 cm. A mature cystic teratoma may be present in the other ovary. Tumors are predominantly solid, with some

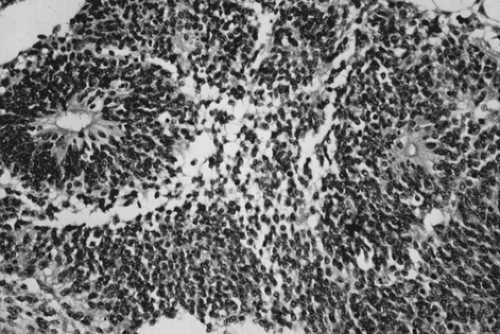

cystic areas filled with serous or mucinous fluid or fatty material (Fig. 61.5). The cut surface is soft and usually gray to pink to brown. Microscopically, the most common immature tissue present is neural, derived from the ectoderm (Fig. 61.6). A histologic grading system was therefore proposed, based on the relative amount of mature and immature neuroepithelial tissues, mitotic activity, and degree of differentiation.

cystic areas filled with serous or mucinous fluid or fatty material (Fig. 61.5). The cut surface is soft and usually gray to pink to brown. Microscopically, the most common immature tissue present is neural, derived from the ectoderm (Fig. 61.6). A histologic grading system was therefore proposed, based on the relative amount of mature and immature neuroepithelial tissues, mitotic activity, and degree of differentiation.

Grade 0: Mature tissue only

Grade 1: Limited immature neuroepithelial tissue and mitotic activity

Grade 2: Moderate amount of immature tissue and mitotic activity

Grade 3: Large quantities of immature tissue and mitotic activity.

Figure 61.5 Immature teratoma. This bulky neoplasm, removed from a 20-year-old woman, weighed 1,800 g. The neuroectodermal elements appeared opaque and friable (arrow). |

Figure 61.6 Immature teratoma. These tumors are graded based on the presence and extent of neuroepithelial elements. Note the rosettes. |

Prognosis correlates with histologic grade of tumors, as the presence of immature elements worsens the prognosis. In patients with stage Ia/grade 1 disease, surgery alone, consisting of an exploratory laparotomy, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and a complete staging procedure (Table 61.3), is sufficient. For more advanced disease, adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery is necessary. Depending on disease extent, preservation of the contralateral ovary and the uterus usually is feasible. Serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels may be elevated (Table 61.2). Chemotherapy is discussed in detail above.

Endodermal Sinus Tumor

Endodermal sinus tumor, or yolk sac tumor, is the second most common germ cell tumor, representing 1% of all ovarian malignancies. It may be pure or part of a malignant mixed germ cell tumor. The reported age distribution ranges from 16 months to 46 years, but most patients are younger than 30 years. The serum AFP level is frequently elevated in these tumors (Table 61.2), making it a useful diagnostic test in the initial workup, in the assessment of response to therapy, and in follow-up for recurrence. Symptoms are typical of those observed with other germ cell tumors. Several cases have presented in pregnancy. No endocrine manifestations have been seen with the pure form of endodermal sinus tumor. More than 70% of endodermal sinus tumors present in stage I, although they are biologically virulent.

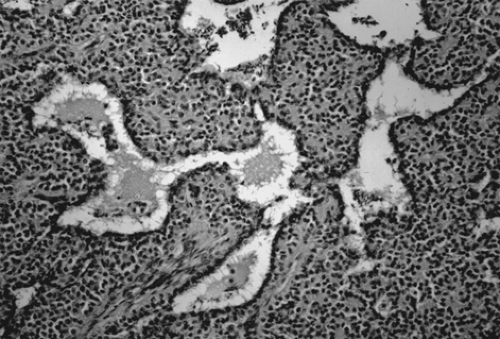

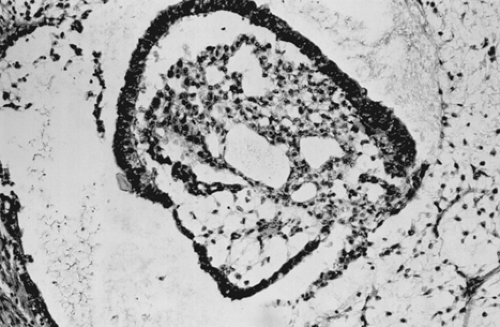

Grossly, tumors are usually gray-yellow, large, and solid, ranging from 3 to 30 cm in diameter. Bilateral involvement has been noted only in patients with metastatic spread to other organs. Foci of hemorrhage, necrosis, and gelatinous changes are present. Microscopically, endodermal sinus tumors display a wide range of histologic patterns. The microcystic pattern is characterized by a loose network of channels and spaces forming a honeycomb lined by flat

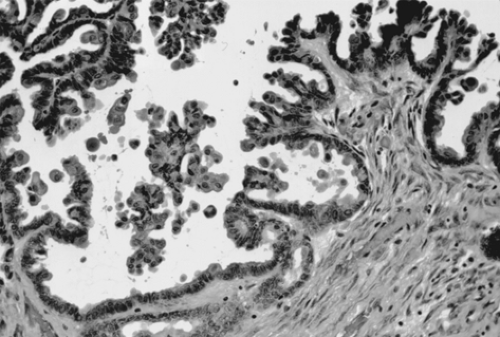

pleomorphic mesothelial-like cells with large hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei. Hyaline globules or droplets, which are positive with periodic acid–Schiff stain, are found commonly. The endodermal sinus pattern is characterized by perivascular formations called Schiller-Duval bodies (Fig. 61.7). Other patterns include the alveolar-glandular pattern, composed of alveolar, glandlike, or cystic spaces lined by flat or cuboidal epithelium; the polyvesicular vitelline pattern, in which numerous small vesicles are surrounded by connective tissue; and the solid pattern, consisting of aggregates of small pleomorphic undifferentiated cells. These histologic patterns do not have prognostic significance.

pleomorphic mesothelial-like cells with large hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei. Hyaline globules or droplets, which are positive with periodic acid–Schiff stain, are found commonly. The endodermal sinus pattern is characterized by perivascular formations called Schiller-Duval bodies (Fig. 61.7). Other patterns include the alveolar-glandular pattern, composed of alveolar, glandlike, or cystic spaces lined by flat or cuboidal epithelium; the polyvesicular vitelline pattern, in which numerous small vesicles are surrounded by connective tissue; and the solid pattern, consisting of aggregates of small pleomorphic undifferentiated cells. These histologic patterns do not have prognostic significance.

Figure 61.7 Yolk sac tumor. A characteristic finding in the endodermal sinus pattern is the Schiller-Duval body. |

In the past, patients with endodermal sinus tumors, even those with early-stage tumors, did poorly despite aggressive surgical and radiation treatments. With adjuvant chemotherapy after conservative pelvic surgery and staging laparotomy (Table 61.3), there has been a marked improvement in the prognosis of patients with this malignancy. Adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens for all nondysgerminomatous germ cell tumors (including endodermal sinus tumors, immature cystic teratoma, embryonal cell tumors, and others) are similar, as they are grouped together in treatment protocols in several major studies. The VAC regimen, first introduced in the 1970s, resulted in a successful cure rate of >80% in stage I disease but <50% in patients with more advanced stage, as reported by a GOG study and the M. D. Anderson experience. The VBP regimen has shown superior results compared with VAC, but toxicity is increased. However, no randomized clinical trials have been performed to compare the two regimens due to the rarity of these malignancies. More recently, the BEP regimen has shown an excellent response rate of >95% in patients with local or advanced disease and has become the primary therapeutic regimen. Further studies, however, are needed to explore alternative regimens to reduce the rate of toxicity while maintaining the same efficacy. Second-look laparotomy should not be a part of posttherapy surveillance for this tumor or any other germ cell tumors. Salvage therapies, such as surgery followed by chemotherapy, in patients who have failed primary chemotherapy have shown some success; however, they are anecdotal at best due to the limited number of cases.

Embryonal Carcinoma

Embryonal carcinoma is rare, accounting for <5% of all germ cell tumors. It usually occurs in children, with a median age of 15 years. Like its testicular counterpart, embryonal carcinoma is a highly malignant neoplasm. Because it is often seen as part of mixed germ cell tumors, serum AFP and hCG levels are often elevated. Clinically, it may be associated with precocious puberty as well as abnormal vaginal bleeding in adults.

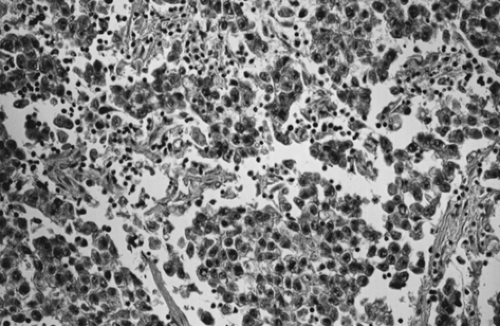

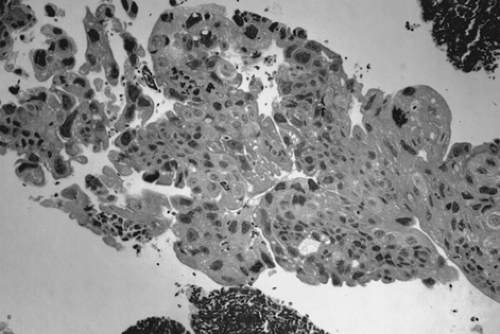

The gross pathologic picture is variable, but the tumor is usually large and soft, with a cut surface that is solid and gray-white with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, embryonal carcinoma consists of primitive, undifferentiated sheets of variably sized epithelial cells (Fig. 61.8). Nuclei are vesicular, and mitoses are frequent. Syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells are frequently seen in the stroma or directly adjacent to clusters of embryonal carcinoma cells.

Polyembryoma

Polyembryoma is a rare germ cell tumor, characterized by numerous embryoid bodies that morphologically resemble normal presomite embryos. It is usually part of a mixed germ cell neoplasm and has similar symptoms. The median age of patients with polyembryoma is 15 years. The tumor is usually unilateral, ranging from 10 cm to a mass that fills the entire abdominal cavity; cut section reveals mostly solid areas with hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, embryonic bodies including an embryonic disk, amniotic cavity, yolk sac, and extraembryonic mesenchyme of

varying degrees of differentiation are noted (Fig. 61.9). Syncytiotrophoblastic cells have also been detected. AFP, hCG, and sometimes human placental lactogen can be demonstrated in the serum and in cells by immunohistochemical staining.

varying degrees of differentiation are noted (Fig. 61.9). Syncytiotrophoblastic cells have also been detected. AFP, hCG, and sometimes human placental lactogen can be demonstrated in the serum and in cells by immunohistochemical staining.

Choriocarcinoma

Choriocarcinoma is a rare germ cell tumor that may be present in either pure or mixed form. Pure choriocarcinoma is usually found in prepubertal children. Isosexual precocious puberty is a common clinical finding in premenarcheal patients. In postmenarcheal patients, the presence of other germ cell components is helpful in distinguishing ovarian germ cell tumors from a gestation choriocarcinoma. A diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is often entertained in postmenarcheal patients due to the shared signs and symptoms. The gross appearance of choriocarcinoma depends on the composition of the germ cell elements. The tumor is usually large, unilateral, and solid with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Microscopically, both cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts are present (Fig. 61.10). Treatment is as described previously for the other germ cell tumors.

Gonadoblastoma

Gonadoblastoma almost always arises in a congenitally abnormal gonad with associated sexual maldevelopment. Patients with gonadoblastoma most often have pure or mixed gonadal dysgenesis or are male pseudohermaphrodites. Predominantly, karyotypes 46,XY, 45X/46,XY mosaicism, and rarely 46,XX or 45,X have been associated with this tumor. Gonadoblastoma is much more common in phenotypic females than in phenotypic males, with a ratio of 4:1. It is frequently associated with dysgerminoma and occasionally with other germ cell neoplasms, including yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, and choriocarcinoma.

Figure 61.10 Choriocarcinoma. There is a dimorphic population of malignant cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts. Associated hemorrhage is a common finding. |

Patients with gonadoblastoma usually complain of primary amenorrhea, virilization, or developmental abnormalities of the genitalia. A karyotype should be included in the evaluation of the young woman with a pelvic mass and any symptoms of abnormal sexual development. It is during the workup of these conditions that gonadoblastoma usually is diagnosed. It is most frequently detected in the second decade. Hot flushes and other menopausal symptoms have been noted after tumor excision, suggesting the presence of estrogen-secreting cells in these tumors. However, the exact source of the androgen or estrogen production is unknown, as the steroid production has been noted in the absence of Leydig or lutein cells.

Gonadoblastoma is more common in the right gonad than in the left and is bilateral in 38% of patients. The tumor can range from a microscopic lesion to a mass measuring up to 8 cm in diameter that is soft and fleshy to firm and hard, depending on the degree of calcification. When mixed with other malignant germ cell elements, it can grow to even larger sizes. Microscopically, gonadoblastoma is composed of cellular nests containing a mixture of germ cells and immature sex cord–stromal cells, such as Sertoli and granulosa cells (Fig. 61.11). Hyaline bodies and calcification are often present in the nests. In 50% of patients, a supervening dysgerminoma displaces most of the gonadoblastoma, pushing the cell nests to the periphery.

Figure 61.11 Gonadoblastoma. Large germ cells are admixed with smaller sex cord derivatives that surround rounded hyaline material resembling a Call-Exner body. |

Treatment for patients with gonadal dysgenesis is a bilateral gonadectomy, because they have an increased risk for a germ cell tumor, especially gonadoblastoma. If the gonads are not removed and tumors develop, the prognosis of patients with pure gonadoblastoma is excellent as long as the tumor and the other ovary are both removed. The prognosis in patients with gonadoblastoma associated with dysgerminomatous elements remains very good, even with metastasis. If the gonadoblastoma is associated with other germ cell tumors, such as endodermal sinus tumor,

embryonal carcinoma, or choriocarcinoma, the prognosis is poor if untreated. However, combination chemotherapy (BEP) results in significant improvement, as described previously.

embryonal carcinoma, or choriocarcinoma, the prognosis is poor if untreated. However, combination chemotherapy (BEP) results in significant improvement, as described previously.

Sex Cord–stromal Tumors of the Ovary

Sex cord–stromal tumor accounts for approximately 5% of all ovarian tumors. The origin of tumor cells may be the coelomic and mesonephric epithelium or the mesenchymal stroma of the genital ridge. This category includes an array of tumors derived from the sex cords (granulosa and Sertoli cells) and from the gonadal stroma (theca and Leydig cells). The most common types of sex cord–stromal tumor are granulosa cell tumors and fibrothecomas, with peak age incidence at approximately 50 years. These tumors have the potential for steroid hormone secretion, with estrogen being the predominant hormone. They are usually not seen in women younger than 20 years, except for juvenile granulosa cell tumors. (The classification of sex cord–stromal cell tumors is outlined in Table 61.5.)

Thecoma

Thecoma is a benign tumor affecting all ages, with a predominance in the postmenopausal group; it is rare in patients younger than 35 years. It accounts for 2% of all ovarian tumors. Many women with a thecoma present with abnormal or postmenopausal uterine bleeding; some present with an endometrial adenocarcinoma as a result of unopposed estrogen production by the tumor. Thecoma is composed of lipid-laden stromal cells resembling theca cells. Rather than arising as a de novo neoplasm, it may represent changes occurring in background cortical stromal hyperplasia.

TABLE 61.5 World Health Organization Classification of Sex Cord–stromal Tumors | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Tumor size ranges from a nonpalpable incidental finding to a large solid mass with a diameter of 15 to 20 cm. It is usually unilateral and almost never malignant. Its outer surface is smooth, and its cut surface is typically solid, lobulated, and yellow. Cystic change may be seen. Microscopic evaluation reveals masses of oval or round cells with abundant, pale, lipid-containing cytoplasm. Hyaline plaques are often noted. A luteinized thecoma sometimes occurs, usually in younger women.

Treatment for thecoma is tailored to patient age and ranges from a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for menopausal or postmenopausal women to a salpingo-oophorectomy or ovarian cystectomy, if possible, in patients who desire future fertility.

Fibroma

Like thecoma, fibroma is also a benign tumor affecting all ages, although most occur in women 40 to 60 years of age; fewer than 10% of patients are 30 years of age or younger. Fibroma is not associated with hormone production. In some cases, hydrothorax and ascites are found in association with a pelvic mass—a constellation of findings known as Meigs syndrome. In other cases, fibroma is seen in patients with a hereditary basal cell nevus syndrome, characterized by early-appearing basal cell carcinomas, keratocysts of the jaw, calcification of the dura, and mesenteric cysts.

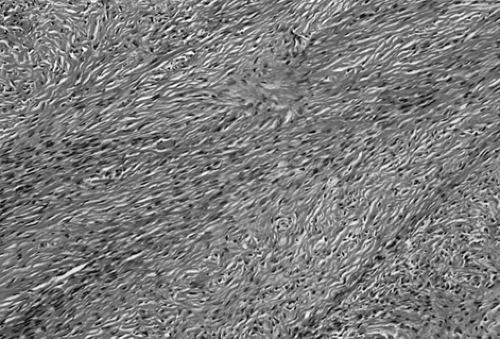

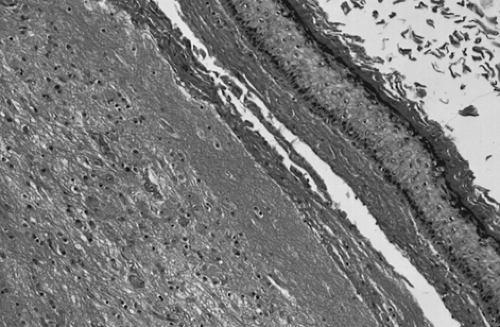

Fibroma, like thecoma, ranges in size from a nonpalpable incidental finding to larger than 20 cm; it is usually unilateral but multinodular. Cut surface is firm and hard and has a whorled appearance. Microscopically, fibroma is composed of bundles of collagen-producing spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern (Fig. 61.12). Hyalinization and intercellular edema are characteristic. The cytoplasm of tumor cells may contain small quantities of lipid, making distinction from thecoma difficult.

Treatment is similar to that for thecoma. In patients with Meigs syndrome, the hydrothorax and ascites usually resolve after resection of the pelvic tumor.

Juvenile Granulosa Cell Tumor

Approximately 44% of all juvenile granulosa cell tumors occur in the first decade of life and 97% in the first 3 decades. Isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty is commonly associated with this tumor, along with Ollier disease (enchondromatosis), Maffucci syndrome (enchondromatosis and hemangiomatosis), and abnormal karyotypes with ambiguous genitalia. Symptoms usually include abdominal pain, increasing abdominal girth, and

hemoperitoneum due to rupture. Occasionally, it may be associated with pregnancy.

hemoperitoneum due to rupture. Occasionally, it may be associated with pregnancy.

The gross appearance of juvenile granulosa cell tumor is commonly a large yellow-to-gray, solid and cystic mass, similar to the adult form. A mixture of granulosa and theca cells may be present. Microscopic features that distinguish juvenile granulosa cell tumor from the adult form are hyperchromatism of the tumor cells, which generally lack grooves, and the frequent luteinization of both the granulosa and theca cells (Fig. 61.13). The follicles are usually immature (Fig. 61.14). Call-Exner bodies, which are pathognomonic of adult granulosa cell tumor, are rarely present in the juvenile form.

Treatment in young women usually consists of a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with a complete staging (Table 61.3), especially if preservation of reproductive function is desired and the tumor appears to be grossly confined to one ovary. Although the survival rate for stage I disease is >90%, juvenile granulosa cell tumor appears to behave more aggressively in advanced disease, with a survival rate of <50%. Isolated reports of successful treatment with various combination chemotherapies have been recorded. Due to the rarity of these tumors, a standard chemotherapeutic regimen has not emerged.

Adult Granulosa Cell Tumor

The adult form of granulosa cell tumor accounts for 1% to 2% of all ovarian tumors and 95% of all granulosa cell tumors. Although these tumors average 10 to 12 cm in diameter, a pelvic mass is not always detectable. Peak age of occurrence is 50 to 55 years, and most granulosa cell tumors produce estrogen, which in premenopausal women is manifested by menstrual irregularities such as menorrhagia,

amenorrhea due to anovulation, or metrorrhagia. In postmenopausal women, vaginal bleeding results from endometrial stimulation. Endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma is a common occurrence, approximately twice that seen in premenopausal women. The best estimate for the frequency of associated endometrial carcinoma is 5%.

amenorrhea due to anovulation, or metrorrhagia. In postmenopausal women, vaginal bleeding results from endometrial stimulation. Endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma is a common occurrence, approximately twice that seen in premenopausal women. The best estimate for the frequency of associated endometrial carcinoma is 5%.

Grossly, the tumors are solid and gray-white or yellow, with cystic areas and hemorrhage. Microscopically, they are composed of granulosa cells and theca cells or fibroblasts, or both. Theca cells and fibroblasts are most likely a response of the ovarian stroma to granulosa cell proliferation, because only granulosa cells are found in metastatic sites. Granulosa cells may be round, polygonal, or spindle shaped, with scant cytoplasm and round or ovoid nuclei. Many different histologic patterns may be seen separately or together; these include the microfollicular pattern with its distinctive Call-Exner bodies (Fig. 61.15), macrofollicular, insular, trabecular, solid-tubular, and rarely hollow-tubular patterns. Less differentiated forms include the watered-silk or diffuse pattern. Rarely, a granulosa cell tumor undergoes sarcomatous transformation, producing the most aggressive form of the disease. Inhibin may be a useful immunohistochemical marker, and serum inhibin levels can be used to monitor the clinical course.

Although most granulosa cell tumors have a very low potential for malignant behavior, with 90% of tumors being stage Ia, they do have a propensity for late recurrence up to 10 to 20 years or more after initial diagnosis. In addition to full surgical staging (Table 61.3), surgery should include a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in postmenopausal patients. Conservative surgery is indicated in younger patients who wish to maintain fertility if the tumor is confined to one ovary. One of the largest series compared the impact of uterine-sparing surgery on survival in young women with stage I disease and found no difference in the 5-year disease-specific

survival between those women who had conservative versus standard surgical staging, 98% versus 97% respectively. Patient age and stage appear to be the most important prognostic factors. Although other prognostic factors include capsular rupture, tumor size, nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and histologic pattern, studies of these factors have not been conclusive. It is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of chemotherapy in this group of tumors. Most retrospective series have been limited by their small sample size and short follow-up. Platinum-based therapy, including the VBP and BEP regimens, has been reported to be the most successful, with a 5-year survival of 50% for patients with advanced-stage disease. Taxane-based regimens have been proposed given the lack of durable remissions and significant toxicity of the BEP regimen. Investigators at M. D. Anderson reported a retrospective study of patients with predominantly granulosa cell tumors who received either BEP or a taxane-based regimen. While there were no statistical differences in clinical outcome, the BEP regimen was associated with higher toxicity. The authors suggest that taxane-platinum–based therapy merits consideration in future prospective trials for sexcord–stromal tumors. Radiotherapy has also been used with varying success in studies limited by small numbers. In recurrent disease, surgery followed by chemotherapy may offer the best mode of therapy.

survival between those women who had conservative versus standard surgical staging, 98% versus 97% respectively. Patient age and stage appear to be the most important prognostic factors. Although other prognostic factors include capsular rupture, tumor size, nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and histologic pattern, studies of these factors have not been conclusive. It is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of chemotherapy in this group of tumors. Most retrospective series have been limited by their small sample size and short follow-up. Platinum-based therapy, including the VBP and BEP regimens, has been reported to be the most successful, with a 5-year survival of 50% for patients with advanced-stage disease. Taxane-based regimens have been proposed given the lack of durable remissions and significant toxicity of the BEP regimen. Investigators at M. D. Anderson reported a retrospective study of patients with predominantly granulosa cell tumors who received either BEP or a taxane-based regimen. While there were no statistical differences in clinical outcome, the BEP regimen was associated with higher toxicity. The authors suggest that taxane-platinum–based therapy merits consideration in future prospective trials for sexcord–stromal tumors. Radiotherapy has also been used with varying success in studies limited by small numbers. In recurrent disease, surgery followed by chemotherapy may offer the best mode of therapy.

Androblastoma and Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor

Hilus Cell Tumor

Hilus cell tumor is a subtype of Leydig cell tumor, originating from the ovarian hilus. The other subtype, which is very rare, is a nonhilar-type Leydig cell tumor derived from ovarian stromal cells and having similar clinical and pathologic features. The average age of patients with a hilus cell tumor is 58 years, and many present with symptoms of abnormal menstruation, hirsutism, and virilization. Some may present with estrogenic manifestations. Hilus cell tumors are almost always benign.

Grossly, this tumor is circumscribed, lobulated, solid, soft, and red to yellow. Tumor enlargement is usually minimal, and the tumor is often physically undetectable. Sometimes, it is incidentally discovered when the ovaries are pathologically sectioned for another purpose. Microscopic evaluation reveals circumscribed masses of steroid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Lipochrome pigment may also be present. The diagnostic elongate eosinophilic crystalloids of Reinke must be found for the tumor to be definitively classified as a Leydig cell neoplasm. Treatment of this benign tumor is unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or ovarian cystectomy if future fertility is desired.

Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are also termed Sertoli–stromal cell tumors and can be further divided into several subtypes (Table 61.5). Stage and tumor differentiation seem to be important prognostic factors. Despite the name of these tumors, hormone production is not always associated with them. Tumors that produce hormones may result in masculine or feminine phenotypes, as few of the tumors actually produce estrogen or progesterone.

Sertoli Cell Tumor

Sertoli cell tumor is very rare. Patients, ranging in age from 7 to 79 years (median, 33 years), usually present with a pelvic and/or abdominal mass. If the mass is functional, patients may present with some form of estrogenic effect, such as endometrial hyperplasia or isosexual precocious pseudopuberty. Androgenic and progestogenic effects may also occur. Most tumors are stage I unilateral masses that are well circumscribed, averaging about 9 cm in diameter. Cut surface reveals solid, yellow-to-brown, lobulated masses. Microscopic evaluation discloses closely packed hollow or solid tubules lined by Sertoli cells that can also contain abundant cytoplasmic lipid. An association between Sertoli cell tumors and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome has been reported in the literature.

Most Sertoli cell tumors are benign or early-stage malignant neoplasms that are cured with surgery. Conservative surgery with a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is indicated in many of these patients who are young and desire preservation of ovarian function. Only rarely are these tumors poorly differentiated and aggressive. Experience with chemotherapy in these tumors is limited due to their rarity.

Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor accounts for <0.5% of all ovarian tumors. It is most often seen in young women, with a mean age of occurrence of 25 years. Fewer than 10% of these tumors occur in women older than age 50 years, and fewer than 5% occur in prepubertal girls. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is often associated with androgen production; however, virilization develops in only 50% patients. This may be due to a lack of hormone production or insufficient androgen production. Typically, patients complain of oligomenorrhea followed by amenorrhea, breast atrophy, acne, hirsutism, temporal balding, deepening of the voice, and enlargement of the clitoris. The latter two symptoms may not resolve after tumor removal. Patients without endocrine manifestations may present with complaints of abdominal swelling or pain. Occasionally, symptoms of estrogen production, due to the Sertoli cell component of the tumor or peripheral androgenic conversion, may be seen such as menorrhagia or menometrorrhagia. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor must be distinguished from other virilizing tumors, such as adrenal tumors, which are often associated with an elevated urinary level of 17-ketosteroids; the urinary level of 17-ketosteroids in Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is usually normal or only slightly elevated. The serum AFP level may be increased and may be useful as a tumor marker.

The gross appearance of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is highly variable. Overall, it has an average diameter of 12 to 15 cm, and its cut surface is usually tan or yellow and may be cystic. Hemorrhage and necrosis are frequently seen in the poorly differentiated tumors. On microscopic examination, the tumor is composed of a mixture of Sertoli, Leydig, and undifferentiated gonadal stromal cells, with or without heterologous components, in varying proportions and degrees of differentiation. In well-differentiated lesions, Sertoli cells from tubules and Leydig cells are found in the intervening stroma (Fig. 61.16). Sertoli cells are cytologically bland, and mitotic figures are rare. Leydig cells may contain abundant lipochrome pigment or crystalloids of Reinke. Intermediate and poorly differentiated tumors are characterized by more immature components of the Sertoli and Leydig cells. Cartilage, mucinous epithelium, skeletal muscle, and other heterologous elements are found in 20% to 25% of these tumors, most of which are of intermediate differentiation. When heterologous elements have been found in poorly differentiated neoplasms, the tumors are clinically malignant. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor with a retiform pattern may be seen with prominent hyalinized cores and papillae lined by stratified epithelial cells.

The treatment for Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor usually depends on patient age and tumor stage, degree of differentiation, and presence of heterologous elements in the tumor. The most important prognostic factor is stage. In young women with a stage Ia well-differentiated tumor who desire future pregnancy, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and a staging procedure are adequate treatment (Table 61.3). However, more aggressive cytoreductive surgery (including a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), tumor resection, and staging procedure may be indicated in postmenopausal patients or in those with more advanced disease.

Figure 61.16 Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. This well-differentiated tumor is composed of hollow tubules lined by Sertoli cells and adjacent sheets of Leydig cells. |

Adjuvant therapy is recommended for patients who have stage Ia lesions with poorly differentiated elements or heterologous components or for those who have heterologous elements or metastatic disease. However, due to the limited number of cases, no standard adjuvant therapy has been accepted for these patients. Most of the information available comes from small series and case reports. Treatment of advanced sex cord–stromal cell tumors, unlike germ cell tumors, has not met with much success. Platinum-based therapies have yielded the best results, with an overall survival of approximately 50%. These include the VAC, VBP, and BEP regimens. As with chemotherapy, radiotherapy has been used successfully in limited cases.

Steroid Cell Tumors Not Otherwise Specified

Termed lipid cell or lipoid tumors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree