Viral Hepatitis

Henry Pollack and William Borkowsky

Many viruses can infect the liver (Table 308-1). Often, infection occurs as part of a disseminated viremia. In this chapter, we focus mainly on the 5 viruses whose primary target is the liver: the hepatitis viruses A through E (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, and HEV).

Hepatitis is both a clinical and a laboratory diagnosis. The best measure of liver injury is the enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT), which is primarily released by hepatocytes during injury or death. Inflammation of the liver can result from a variety of causes. In the evaluation of a patient with hepatitis, it is also necessary to consider nonviral diseases of the liver that can cause similar symptoms (see Chapter 419). Because of the large number of potential viral causes of hepatitis, the evaluation of a patient can be confusing and complicated. The clinical context in which disease presents is the key to directing the work-up (see Table 308-1). If just the transaminases are mildly elevated, then waiting and repeating these test might avoid an extensive and costly evaluation. Identifying the causative agent may not be critical for an asymptomatic transient elevation of transaminases. In symptomatic disease, it is impossible to establish the causative agent from symptoms alone.

Table 308-1. Viral Causes of Hepatitis Based on Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

Epidemic: Generally HAV or HEV |

Classical clinical features: HAV, HBV, HCV |

Sporadic: HBV, HCV |

Clustering within a family: HBV, HCV, inherited |

Birth, travel, or blood exposure in country where infection is endemic: East/Southeast Asia (HBV); Africa (HBV); Caribbean and South America, especially Amazon region (HBV); eastern Europe (HBV, HCV); South Asia (HBV, [Pakistan HCV > HBV]); foreign travel (HAV > HBV > HEV); injection use (HCV > HBV); transfusion (HCV > HBV) |

Fulminant: HAV > HBV |

Age: Newborn and infant (CMV > HSV, HHV-6, enterovirus, LCM, rubella), child or adolescent (EBV, CMV) |

Transient: Enteroviruses, influenza, viremias (HSV, varicella, HHV-6, HHV-7), parvovirus, adenoviruses, rubella, rubeola |

Persistent: EBV, CMV, HIV, congenital (rubella, CMV, HSV), LCM |

Chronic: HBV, HCV, HDV |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; HHV, human herpes virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; LCM, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.

HEPATITIS A

HAV is a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus that is classified as a picorna virus. First identified in the 1970s, it is the major cause of infectious hepatitis. There are several genotypes but only 1 known serotype. HAV causes acute hepatitis and asymptomatic infection but never chronic infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HAV is the most frequent cause of epidemic hepatitis in the United States with rates highest in the western United States. Approximately 5000 to 10,000 cases are reported each year. This number represents only 10% of the estimated new cases. Approximately one fifth of cases occur in children under the age of 15. Infection occurs primarily via the fecal-oral route because the virus is relatively resistant to gastric acidity, making it an extremely efficient gastrointestinal pathogen. Infection can also occur by percutaneous exposure to blood (intravenous drug use) or exceptionally by transfusion. In 50% of cases, no source is identified. HAV is highly contagious within families and close contacts (sexual partners). Men who have sex with men are also at high risk of infection. The rates of HAV infection have declined dramatically, especially in children, with the introduction of the HAV vaccine in 1995.1 Epidemics are generally caused by person-to-person transmission or by contaminated food or water products. Daycare outbreaks and community-wide outbreaks were common before the introduction of the vaccine. Travel to countries where HAV is endemic is also a frequent cause of sporadic infection. In countries where it is endemic, infection is usually acquired in childhood and is often asymptomatic.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

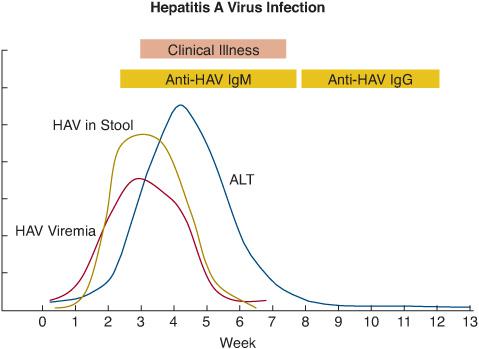

HAV replicates in the liver; it is excreted in the bile and shed in the stool. The incubation period is between 2 and 6 weeks (average 4 weeks). A period of viremia precedes the presence of virus in stool and continues through the period of elevated liver enzymes.2 Clinical disease occurs after shedding in stool has begun (Fig. 308-1). The period of peak infectivity is during the 2 weeks prior to jaundice or elevated ALT and alkaline phosphatase. Shedding of virus can persist for several months in young children.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The frequency of clinical symptomatology is a function of age, ranging from less than 10% in young children to approximately 50% in older children and more than 80% in adults. Symptomatic acute infection usually begins abruptly with fever, nausea, abdominal pain, malaise, fatigue, anorexia, jaundice, and dark urine. Symptoms generally subside by 2 months. The severity of disease increases with age. Fulminant infection occurs in 1% to 2% of cases and is associated with a mortality as high as 50% even with liver transplantation.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The diagnosis is made serologically by the detection of HAV IgM during the acute phase of infection. Lifelong immunity is conferred by HAV IgG, a marker of prior infection. The virus can also be recovered by polymerase chain reaction in the blood or stool. Complications include severe hepatitis and prolonged cholestatic hepatitis and are more common in adolescents, adults, and persons with chronic liver diseases.

In the absence of specific treatment of acute HAV, supportive care remains the only treatment option. Symptoms generally subside after a few weeks. In the case of fulminant hepatitis, early referral for liver transplantation is critical. In most cases, the prognosis is excellent. Occasionally, relapsing hepatitis lasting up to 6 months may occur. Recovery provides lifelong protection from reinfection.

PREVENTION

PREVENTION

Improved sanitation, purified water, and better hygiene are key strategies in reducing environmental exposure to HAV and preventing large-scale epidemics. An individual can be protected from acquiring disease after exposure to HAV by the use of either gamma globulin injections (intramuscularly) or the HAV vaccine,3 which has been licensed since 1995. Immunization against HAV is now recommended starting at age 12 months.4

FIGURE 308-1. Time course of virologic, serologic, and clinical events during acute hepatitis A infection. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

HEPATITIS B INFECTION

HBV is the smallest (3.2 kb) and one of the most successful human viruses, having been present among humans for at least 3000 years. HBV, a DNA virus, goes through an RNA-polymerase cycle that is responsible for a high rate of mutation as well as for the virus’s sensitivity to nucleosides and nucleotides that act also on retroviral reverse transcriptase.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HBV infects more than 1 billion people and chronically infects 300 million to 400 million persons, making it one of the most common viral infections worldwide. It is responsible for 80% of the cases of primary liver cancer worldwide that claim an estimated 500,000 lives each year. Transmission occurs percutaneously, sexually, via mucous membranes, and vertically from mother to infant. Infection acquired in infancy, when chronic infection is most likely to occur, accounts for the largest portion of chronic HBV worldwide. Areas of high prevalence (> 2%) include Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and South America. The seroprevalence in the United States is low, and new cases of acute HBV have declined dramatically since the introduction of the hepatitis B vaccine. By contrast, the number of cases of chronic infection has increased to 1.4 million with the influx of immigrants from countries of high prevalence. This accounts for most of the cases of chronic HBV in children seen in the United States. In addition, there are an estimated 20,000 chronically infected pregnant women who deliver each year, but very few of their children develop chronic HBV since the implementation of universal perinatal HBV prophylaxis in the United States in 1991. Even with adequate prophylaxis, up to 25% of infants born to mothers whose viral load is higher than 109 copies/ml will become infected.5 Asian Pacific Islanders account for approximately 60% of the cases of chronic HBV in the United States, and overall, they are more than a 30 times as likely as Caucasians to be infected with HBV than Caucasians. Other groups with high prevalence are Africans, Eastern Europeans, Haitians, and South Americans from the Amazon Basin. Other groups of children who have higher rates of chronic HBV are adolescent males who have sex with males and intravenous drug users. Genotype distribution varies by geography. The most common genotype among non-Asians in the United States is genotype A, whereas it is genotype B and C among Asian Pacific Islanders.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

HBV is found in extremely high amounts in blood but also can be found in high titers in urine and saliva, directly correlating with blood levels. The risk of infection is related to the dose of virus in the donor and the volume of the infectious exposure. In the case of neonates exposed to E antigen (eAg)-positive (which correlate with 106-12 viral particles/mL of blood) mothers, the risk of infection exceeds 90% but is less than 30% when born to eAg-negative (correlating with < 106 particles/mL) mothers. After exposure, there is local replication, uptake by dendritic cells, then viremia and infection of almost all hepatocytes where active replication occurs. The incubation period is 6 weeks to 6 months.

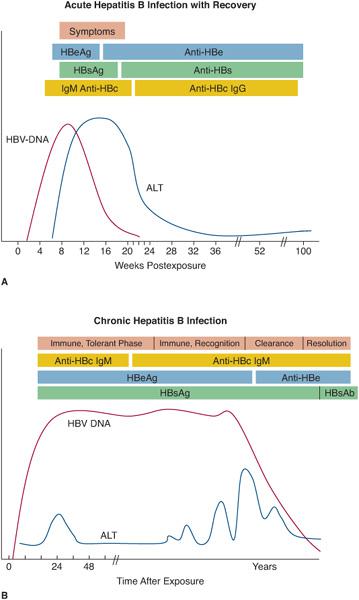

Whether a person develops chronic infection depends mostly on the age at the time of exposure (from > 90% at birth, 40% up to age 5, < 2% in adolescence and young adults), genetic factors (HLA class II genes and tumor necrosis factor-polymorphisms) and the competence of the immune system. Even after resolution of acute infection, HBV can be found in the liver by polymerase chain reaction and, like varicella, can recrudesce after immune suppression or during periods of incompetence. Resolution of infection after exposure involves T cell–mediated immunity, either cytokine-mediated or via cytolytic mechanism. The stronger the cytolytic response, the greater will be the severity of the clinical manifestations. HBV by itself is nonnecrotizing and does not cause obvious hepatotoxicity or ALT release. Therefore, the clinical course can range from asymptomatic infection to fulminant infection wherein most of the host’s hepatocytes are destroyed by the person’s own cytotoxic T cells. Chronic infection often is accompanied by repeated episodes of T cell–mediated immunity against infected hepatocytes that leads to flares of ALT and, over time, fibrosis, scarring, and cirrhosis. ALT rises are surrogate markers of the patient’s immune response to the virus. Resolution of infection is marked by the disappearance of the circulating viral surface antigen (HBsAg) and the appearance of antibody to the antigen (HBsAb) (Fig. 308-2A). If infection persists for longer than 6 months, the patient is considered to have chronic infection.

While the hallmark of chronic infection is the presence of HBsAg, the staging of infection requires a more complete laboratory analysis. A core-related antigen (HBeAg) that correlates with viral load was used as a marker of high viral activity, but mutations can abolish eAg production (eAg-HBV) yet sustain high viral activity, rendering it unreliable for this purpose. The most important determinant of long-term outcome of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cirrhosis is viral load, with marked increased risk with viral loads greater than 104 copies/mL.6Integration of HBV genome in host DNA is responsible in part for the risk of HCC. In chronic HBV infection, HCC can occur without cirrhosis, distinct from HCC resulting from chronic HCV. This has implications for the different monitoring strategies for HCC in these 2 infections.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms of acute HBV and chronic HBV infection can sometimes overlap. Usually, however, the syndromes are quite distinct. Acute infection can be asymptomatic or clinically apparent, with resolution. Severe, acute, and fulminant hepatitis leading to rapid liver failure (bleeding, encephalopathy, low glucose) occurs in about 1% of clinically apparent infections, which is less common than in acute HAV infection and often requires liver transplant for survival. The severity of severe disease is related to viral (mainly precore and core promoter mutations) and host factors. Although rare in incidence, the most common cause of fulminant HBV in neonates and infants eAg mutants.7

There are usually at least 4 phases of chronic HBV infection (Fig. 308-2B). Initially, the patient goes through an immunotolerant phase characterized by high viral load and normal ALT. At this stage, the infection is usually completely asymptomatic. This phase can last several decades, especially if infection occurred vertically or during early childhood. Viral loads are generally in the 108 to 1010 copies/mL range. The beginning of an immune response is heralded by a rise in ALT. This begins the phase of immune recognition. If the immune response is effective, the viral load will begin to decline and eAg clearance may occur during the phase of immune clearance. During this phase, flares in ALT more than 10 times the upper limit of normal may occur, and occasionally they will be accompanied by jaundice and other symptoms of acute HBV infection. These flares are self-limited, but if they occur often enough, they may lead to marked fibrosis and cirrhosis. In children, these 2 phases most frequently occur during adolescence, often after puberty when the rates of eAg clearance can be as high as 15% per year. HBsAg may clear, signaling that the infection has resolved, but this is much less likely (only about 1% per year), and even after clearance, it can be detected in the liver by polymerase chain reaction.

Because of the time it takes to develop cirrhosis, it is much less common in children (< 5%), as is end-stage liver disease and hepatomas. Most commonly, they occur after 4 to 6 decades, especially in men 40 to 55 years of age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree