Venipuncture and Peripheral Venous Access

Mananda S. Bhende

Mioara D. Manole

Introduction

Venipuncture and peripheral venous access remain two of the most common yet most challenging procedures in pediatric medical care. Many providers who do not treat infants and children on a regular basis are uncomfortable performing these procedures. Consequently, children, parents, and health care professionals alike may be anxious when obtaining blood or inserting an intravenous catheter becomes necessary.

Venipuncture, as the name implies, consists of puncturing a vein, and it continues to be the primary method of obtaining blood samples in children, usually preferred to finger stick, heel stick, and arterial puncture. Peripheral venous access provides a means of maintaining or replacing body stores of fluids or blood volume, restoring acid-base balance, and administering medications. These two procedures can be used for all pediatric age groups. They are commonly performed by many health care professionals in hospital and prehospital settings, offices, outpatient facilities, and, through the efforts of trained visiting nurses, in the patient’s own home. If peripheral venous access is not easily obtained in emergent settings, alternative routes include central venous access (Chapter 19), intraosseous access (Chapter 21), and venous cutdown catheterization (Chapter 20). Peripheral venous access is a short-term, definitive procedure that can be used for 48 to 72 hours. After that time, access should be changed because of increased incidence of thrombophlebitis and infection. If long-term access is needed or hyperosmolar solutions must be administered, the patient will generally require central venous access.

Anatomy and Physiology

Sites available for peripheral venous cannulation and venipuncture include multiple locations in the upper and lower extremities, the scalp, and the external jugular vein. The veins are larger and generally easier to locate in adults than in children. In states of intravenous depletion or shock or in the well-nourished toddler with chubby hands and feet, intravenous access can be difficult for even the most experienced personnel.

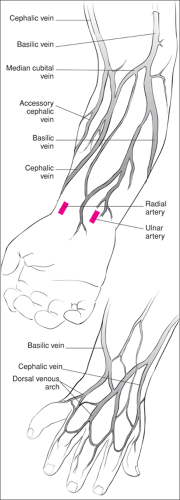

Upper Extremity

On the dorsum of the hand, the most commonly used veins are the tributaries of the cephalic and basilic veins and the dorsal venous arch (Fig. 73.1). The cephalic vein, which is located on the radial border of the forearm just proximal to the thumb, is predictable in its location. It is a large vein that is well secured to the fascia, making it unlikely to move or “roll” during venipuncture or venous cannulation. In the forearm, the cephalic, basilic, and median cubital veins may be difficult to locate in a younger child because of subcutaneous fat. Veins on the volar side of the wrist, if visible, can also be cannulated. It is important to avoid puncturing the radial or ulnar arteries or nerves that lie in close proximity to these vessels. The axillary vein is a continuation of the basilic vein and should be used with caution for peripheral venous cannulation.

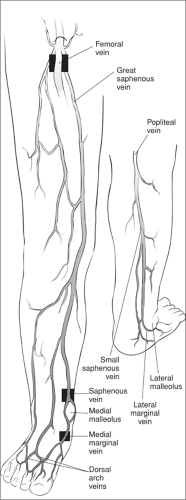

Lower Extremity

The saphenous vein, which is situated about 1 cm above and in front of the medial malleolus, is a good choice for cannulation (Fig. 73.2). It is large and well secured by fascia, which prevents it from rolling when cannulation is attempted. Because of its reliably predictable location, it is one of the few veins appropriate for attempting access by location alone (i.e., a “blind stick”). The median marginal veins and the veins of the dorsal arch of the foot also may be accessed. The anterior and posterior tibial veins form the popliteal vein, which continues

as the femoral vein. The long saphenous vein drains into the femoral vein. When the patient is critically ill and peripheral venipuncture proves impossible, the femoral vein, which is a site for central catheterization, may be used for venipuncture. In the femoral triangle, the anatomic relationship from lateral to medial is nerve, artery, vein, and lymphatic, often expressed by the acronym NAVL. This relationship can be remembered using the mnemonic “NAVL towards the navel.” Therefore, if the clinician can palpate the arterial pulsations, the vein lies immediately medial to the pulsations. The femoral artery lies midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis 1 cm below the inguinal ligament. Using this anatomic landmark, the femoral vein can be punctured in cases when the artery is not palpable (e.g., hypotension). Cannulation of the femoral vein, an approach for central venous access, is described in Chapter 19.

as the femoral vein. The long saphenous vein drains into the femoral vein. When the patient is critically ill and peripheral venipuncture proves impossible, the femoral vein, which is a site for central catheterization, may be used for venipuncture. In the femoral triangle, the anatomic relationship from lateral to medial is nerve, artery, vein, and lymphatic, often expressed by the acronym NAVL. This relationship can be remembered using the mnemonic “NAVL towards the navel.” Therefore, if the clinician can palpate the arterial pulsations, the vein lies immediately medial to the pulsations. The femoral artery lies midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis 1 cm below the inguinal ligament. Using this anatomic landmark, the femoral vein can be punctured in cases when the artery is not palpable (e.g., hypotension). Cannulation of the femoral vein, an approach for central venous access, is described in Chapter 19.

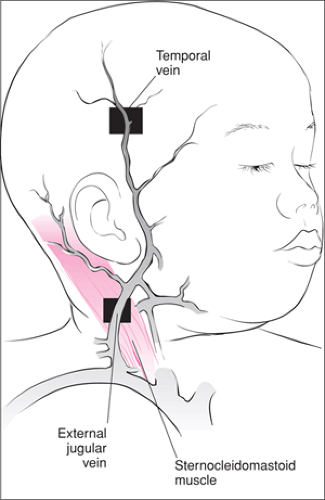

Scalp Veins

Scalp veins are prominent in infants, especially those under 3 months of age. From a practical standpoint, scalp veins may be accessed in patients up to the age of about 9 months if the hair is relatively thin. The scalp veins are closer to the surface and are supported underneath by the bony cranium (Fig. 73.3). They can be used for both venipuncture and venous access. Scalp veins are not generally accessed when airway management is in progress because of space limitations and movement of the head and neck. Scalp arteries and veins should be differentiated by palpation. Arteries are generally more tortuous than veins. Blood flow through the scalp arteries is away from the heart, whereas blood flow through the scalp veins is toward the heart. The clinician can lightly press the vessel with fingers and block the blood flow at two points. Releasing one point and watching the vessel refill will reveal the direction of blood flow. If there is no refill, the procedure is repeated releasing the other pressure point on the vessel. If an artery is cannulated by mistake, fluid instillation will cause immediate blanching in the surrounding area, which will indicate that the catheter should be removed. The temporal veins anterior to the earlobe are the largest and the easiest to locate. The frontal vein down the middle of the forehead is another good choice.

External Jugular Vein

The external jugular vein is usually cannulated by physicians rather than nurses because of its location (Fig. 73.3). Despite its location in the neck and proximity to the central circulation via the subclavian vein, the external jugular vein is a peripheral vein. It is typically used only when cannulation of other peripheral sites is unsuccessful or when considerable time may be saved in managing a critically ill infant or child. As with scalp veins, the external jugular vein can be a problematic site to use during resuscitative efforts because accessing it interferes with airway management. It extends from the lower lobe of the ear to the medial clavicular head across the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Since it cannot be palpated, the external jugular vein must be visualized, which is best accomplished by having the patient in the Trendelenburg position with the head turned away from the site to be punctured.

Indications

Venipuncture is indicated whenever blood sampling requiring more than 1 mL is needed for laboratory analysis. Venipuncture is also the method of choice for obtaining specimens for blood culture.

Obtaining venous access is indicated when medications, fluids, blood products, or contrast material must be administered by the intravenous route to a patient. Examples of such situations are numerous and include volume depletion, respiratory compromise, severe pain, infection, cardiac abnormalities, and multisystem trauma. Any potentially life-threatening condition requires placement of a peripheral intravenous line as a means of ensuring adequate access should a complication develop.

For pediatric resuscitations, peripheral venous access is the accepted mode to treat the patient. With adult resuscitations, central venous drug administration may provide more rapid onset of action and higher peak concentrations than peripheral venous administration (1). However, this has not been demonstrated in pediatric arrest models. In pediatric animal and human resuscitation, peripheral administration, central administration, and intraosseous administration result in comparable onset of drug action and peak drug levels, particularly if the drug is followed by a bolus of normal saline (2).

Absolute contraindications to venous cannulation are cutaneous infection overlying the vein chosen for cannulation, presence of phlebitis or thrombosis of the vein, poor perfusion, and marked edema of the extremity. Relative contraindications include burns overlying the venipuncture site and trauma of the extremity. In a patient with neck or upper chest trauma, the ipsilateral arm should not be used to place an intravenous line because the integrity of the proximal veins cannot be ensured. With a gunshot wound or massive trauma to the abdomen, intravenous lines should preferably be started in the upper extremities rather than the lower extremities for the same reason. Care must be also taken when starting intravenous lines in patients with coagulation defects or abnormal blood vessels.

Equipment

It is important to have all the equipment ready and organized so that the clinician does not have to look for necessary items in the midst of the procedure. Mobile intravenous carts that have all the equipment stored in one place are a good solution (Table 73.1). These carts should be stocked at least daily. The top of the cart can be used as the area where equipment needed for the patient is placed. The cart should also have its own sharps disposal unit.

TABLE 73.1 Intravenous Cart Equipment List | |

|---|---|

|

Tourniquets can be round or flat rubber tubing. They are applied proximal to the desired vein to produce temporary venostasis by occlusion. For scalp veins, a rubber band is used. A piece of tape is placed at some point on the rubber band with the two sticky sides together so that the rubber band can be removed using the tape as a “handle.” This prevents the rubber band from snapping against the infant’s head. Ten percent povidone-iodine (Betadine) prep pads or sticks, which are antiseptic and microbicidal, are first used to prepare the area. Then 70% alcohol pads can be used to clean off the Betadine, allowing visualization of the veins. Povidone-iodine is superior to alcohol as an antiseptic agent (3). In fact, using alcohol pads alone has been shown to be no better than using no antiseptic agent in terms of infectious complications.

Butterfly needles are fine metal cannulas also known as scalp needles. Needles and catheters are sized by their diameter using an inverse measurement known as “gauge”—the smaller the diameter, the larger the gauge. Butterfly needles were once synonymous with pediatric vascular access but now range in size from 25 gauge (smallest) to 19 gauge (largest). Butterflies are used for venipuncture, arterial puncture, and, very rarely, short-term vascular access. In children they are preferred over a needle attached to a syringe for venipuncture because it is easier to manipulate a butterfly into tiny veins and it offers better control while drawing the blood. Butterfly needles are not optimal for providing vascular access, as any movement can lead to vessel perforation by the sharp needle tip even after securing it in place.

Intravenous over-the-needle catheters are used most commonly for venous access. They are composed of thin-walled, semiflexible plastic tubing over a hollow needle. Once inside the vein, the plastic covering is threaded in the vein, and the needle is withdrawn and discarded. Over-the-needle catheters range in size from 26 to 14 gauge. Appropriate catheter sizes for pediatric patients are as follows: 22 and 24 gauge for infants; 20, 22, and 24 gauge for young children; 16 and 18 gauge for adolescents. For adolescents with multisystem trauma and/or severe shock, a 14-gauge catheter may be needed. Over-the-needle infusion catheters cause minimal endothelial irritation and therefore are the most popular choice for peripheral venous access. As mentioned previously, however, they are not indicated for long-term use. Attention to blood and body fluid precautions has led to the development of closed systems where blood stays within the capped tubing (4) as well as intravenous catheters that are retractable inside a plastic shield, plastic shields that slide over the needle, and self-sheathing angiocatheter needles (see also Chapter 8).

Padded armboards of different sizes should be available to immobilize an extremity as needed. Sterile gauze pads (2″× 2 ″) are placed near the intravenous site, but around the taping area 4″× 4 ″ clean (nonsterile) gauzes may be used. Sterile, transparent occlusive dressings (e.g., OpSite, Smith and

Nephew; Tegaderm, 3M Health Care), which allow visualization of the puncture site, can also be used to secure the catheter.

Nephew; Tegaderm, 3M Health Care), which allow visualization of the puncture site, can also be used to secure the catheter.

Procedure

Preparing the Patient

Verbal consent is usually sufficient before venipuncture or placement of a peripheral intravenous catheter. It is essential to prepare the patient and the parent for the procedure, which they may view as an ordeal. In an emergent situation (e.g., cardiac arrest or a seizing child), the clinician should not take time to explain all details of the procedure. A quick explanation that an intravenous line needs to be started to give medications is adequate. This can be explained by a staff member helping with the care of the patient (5).

When obtaining venous access is not emergent, it is important to discuss the reason for the procedure with the parents and patient in terms they understand. The clinician should explain that there will be a “pinch” when the needle and plastic catheter go into the vein but that the needle will be removed, leaving only the catheter in the vein to give fluids and medications. The child may understand better if told that it is like a straw through which “water and medicine” that will make the child better can be given. Because the pinch hurts, the child should be told that it is okay to cry but that it is important to remain as still as possible. If time allows, explaining with dolls or stuffed animals may also help. This is usually possible for elective procedures done outside the ED and occasionally in the urgent setting. While such measures do not lessen the pain of the procedure, taking time to allay fears will decrease the amount of emotional trauma experienced by the child.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree