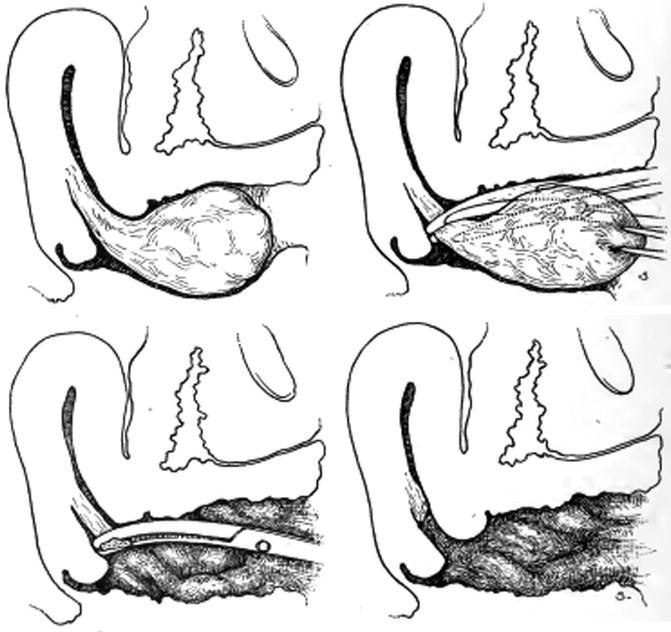

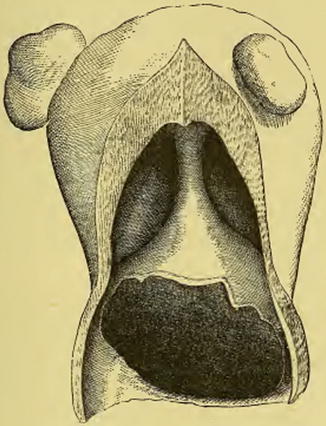

Fig. 14.2

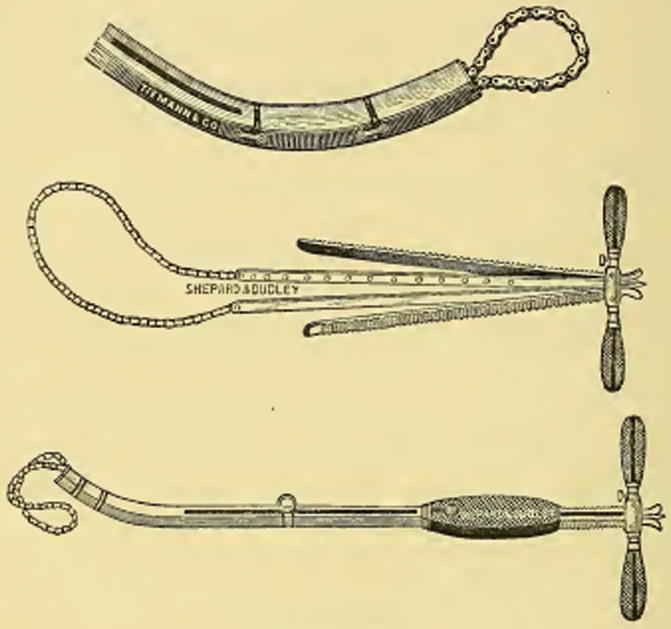

Emmet’s écraseur chain which is placed around a fibroid polyp to lacerate and crush the tissue and facilitate the application of a suture (Taken from Ref. [2])

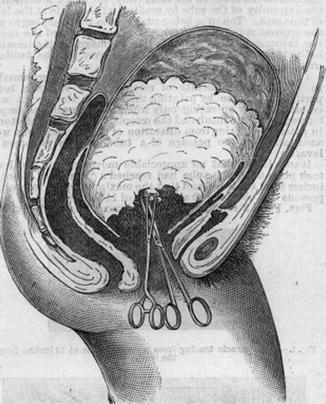

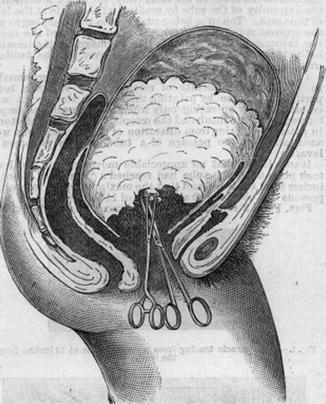

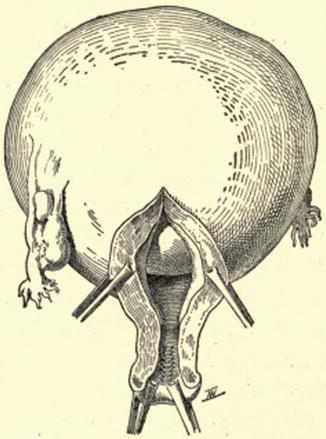

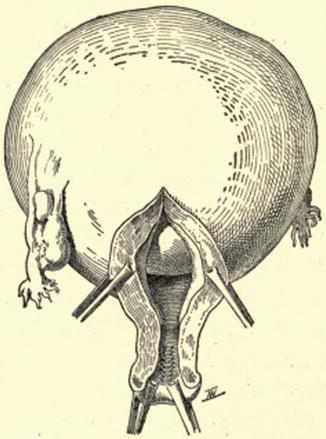

Fig. 14.3

Pedunculated intracavitary fibroid, partially removed by the écraseur (Taken from Ref. [3])

While there were a wide range of indications for vaginal myomectomy, fibroids which were over-large, which Noble who wrote the chapter defined as “several pounds”, and “lack of room in the vagina” were considered to be relative contra-indications, although incising the perineum was an option in cases of the latter. However, one cannot but get the impression that relatively large fibroids were being removed vaginally as well demonstrated by a case report published in the British Medical Journal in 1893. Dr. James Murphy, then President of the North of England Branch of the British Medical Association, described a patient with a myomatous uterus extending up to the umbilicus who underwent a successful vaginal myomectomy using the technique of “morcellement” popularized by Jules-Émile Péan (Fig. 14.4) [4].

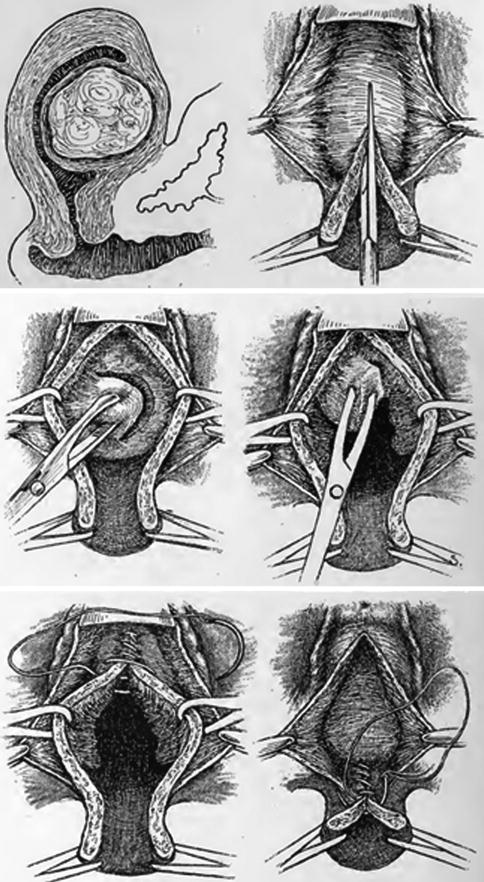

Fig. 14.4

Vaginal myomectomy “par morcellement” (Taken from Ref. [4] With permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd)

Another surgical textbook, “Operative Gynecology” written by Harry Sturgeon Crossen (USA) and published in 1917, is worthy of study as it included beautiful illustrations of the various different types of vaginal myomectomy, some of which I have included for demonstration purposes later in this chapter [5]. Many of these classic books are available for download for free from www.archives.org, a website well worth a visit.

Classification of Vaginal Myomectomy

As the term vaginal myomectomy relates to several different procedures, we have found it useful to classify the various types of vaginal myomectomies, and now use the system summarized in Table 14.1 [6].

Table 14.1

Classification of vaginal myomectomy

Type | Description |

|---|---|

1 | Avulsion of prolapsed pedunculated submucous fibroid |

2 | Non-incisional access to intracervical or intracavitary fibroids |

3a | Dührssen cervical incision to access to intracavitary/submucous/intramural fibroids |

3b | Hysterotomy to access to intracavitary/submucous/intramural fibroids |

4 | Anterior or posterior colpotomy to access to intramural and subserous fibroids |

There are basically four approaches which can be used depending on the position and size of the fibroid or fibroids. Prolapsed submucous fibroids are ideally removed through the cervix (Type 1 procedure). Cervical dilatation or a cervical/uterine incision (Types 2 and 3a/b procedures respectively) can be used to access fibroids higher in the uterus, whether they are intracavitary, submucous or intramural. Intramural fibroids can also be approached via an anterior or posterior colpotomy, and this is the route of choice for those which are subserous (Type 4 procedure).

Type 1 Vaginal Myomectomy

The avulsion of a submucous (or cervical) fibroid which has prolapsed into the vagina is the simplest and at the same time the original vaginal myomectomy as described by the early pioneers such as Ammusat and Atlee. In contrast to the other types of vaginal myomectomy, this is the technique which historically has not been abandoned as is evident from published series as well as textbooks of today [7–10]. Such patients typically present with heavy, unscheduled vaginal bleeding, and examination confirms a mass in the upper vagina. The excision of a prolapsed fibroid in the vagina has also been reported after pregnancy, the typical scenario being of a major postpartum haemorrhage which is resistant to uterotonic drugs [11, 12] (Fig. 14.5).

Depending on the size and vascularity, the fibroid can be excised by twisting its pedicle or following clamping, cutting and suturing the base. Whichever technique is used, we routinely carry out a hysteroscopy afterwards to check that the fibroid has been completely removed; if not, any residual fibroid tissue in the uterine cavity can be resected. If the cervical canal is too dilated to allow sufficient uterine distension, we place a couple vulsellums on the cervix or even perform a temporary cervical cerclage to narrow the cervix and reduce the leakage of uterine irrigant.

Type 2 Vaginal Myomectomy

If a fibroid is in the cervical canal or in the lower uterine cavity, it may be possible to remove it vaginally without cutting the cervix. In the non-pregnant uterus, cervical dilatation with conventional mechanical dilators or preparation with laminaria tents (Laminaria japonica) may be required to allow sufficient access prior to avulsion or morcellation in the case of larger fibroids, as, for instance, described by Milton Goldrath [13, 14]. However, unless the fibroid is small, our preference is to carry out a Type 3 procedure and cut the cervix using a Dührssen’s incision in such cases, as described in the next section, as in our view this affords better access to the uterine cavity.

The situation may well be different after pregnancy. Martindale et al. described a case of secondary postpartum haemorrhage which was managed by the vaginal removal of an 8 cm submucous fibroid without cutting the cervix [15].

Type 3a Vaginal Myomectomy

Alfred Dührssen (1862–1933) was a prominent figure in German gynaecology, and the cervical incisions which bear his name, typically consisting of 3–4 cervical incisions extending up to the vagina, were originally used to allow immediate vaginal delivery of the fetus before full dilatation [16]. Dührssen’s incision was adapted for the performance of vaginal myomectomy in the nineteenth century as it facilitated access to fibroids which would otherwise be inaccessible and made the removal of relatively large intracavitary fibroids possible with the aid of morcellation. As an example of the technique, Fig. 14.6 is taken from “Gynecological operations, including non-operative treatment and minor gynecology” by Henri Hartmann published in 1913 [17].

Fig. 14.6

Vaginal myomectomy done with the help of a posterior Dührssen’s incision (Taken from Ref. [17])

We prefer to make a posterior rather than anterior cervical incision as this avoids any risk of bladder injury, but if we suspect that the incision may have to be extended into the uterine body as a hysterotomy, we start with an anterior Dührssen’s incision as in our experience it is easier to repair an anterior hysterotomy than a posterior one. Either way, once the cervix has been cut, the fibroid is grasped with strong forceps such as a vulsellum or Lane’s tissue forceps and enucleated with or without morcellation. Following the myomectomy, the cervical incision is repaired (Fig. 14.7).

Fig. 14.7

Excision of a large submucous fibroid with the aid of a Dührssen’s incision and morcellation. (a) A osterior Duhrssen’s incision is made. (b) The fibroid is grasped with tissue forceps. (c) The fibroid is avulsed. (d) Appearance of the cervical incision after removal of the fibroid. (e) The cervical incision is sutured. (f) The appearance of the cervix on completion of th surgery

At our institution, a type 3a vaginal myomectomy is considered an alternative to hysteroscopic myomectomy in women with larger type 0 or 1 submucuous fibroids sited in the lower uterine cavity. With fibroids >5 cm in diameter, most gynaecologists are reluctant to offer hysteroscopic surgery, but as demonstrated above, there is no reason why myomectomy cannot be done vaginally using this technique combined with morcellation. In fact, in our view, the procedure should be considered even if the fibroid is smaller. For instance, the hysteroscopic resection of a 4 cm fibroid is time consuming, and with longer operating times comes the risk of fluid overload. Vaginal myomectomy in such cases is not only much quicker, but fluid overload is impossible.

Type 3b Vaginal Myomectomy

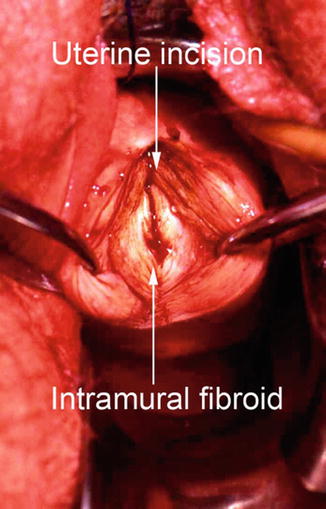

It is, however, extension of the cervical incision into a hysterotomy which, above all, increased the versatility and indications for vaginal myomectomy. Fibroids which are intramural or sited in the upper uterine cavity, and which are seemingly out of range for the vaginal surgeon even if the cervix is cut become a realistic target following a hysterotomy. As demonstration of this, Fig. 14.8 is taken from “Operative Gynecology” published in 1917.

If an anterior hysterotomy is used, which is our preference, the bladder invariably has to be dissected away from the cervix and anterior uterine wall to protect it from injury. To do this, we make an anterior semi-circular transverse incision at the cervico-vaginal junction and dissect the bladder upwards before incising the cervix and uterine body anteriorly in the midline. Occasionally, this results in an anterior colpotomy being made, but that is of no consequence.

A type 3b vaginal myomectomy is suitable for excising large intracavitary, submucous or intramural fibroids (Fig. 14.9). In such a case, morcellation allows the fibroids to be debulked piecemeal, and various morcellation techniques have been described as shown from this series of drawings taken from “Gynecological operations, including non-operative treatment and minor gynecology” published in 1913 (Fig. 14.10).

Fig. 14.9

Anterior hysterotomy to gain access to a large intracavitary fibroid (Taken from Ref. [17])

Fig. 14.10

Two types of morcellation techniques, (a) lozenge, (b) Echelle or ladder, (c) result of Echelle morcellation (Taken from Ref. [17])

Irrespective of the size of fibroid, dissection of the pseudocapsule is done with fingers or Mayo scissors while exerting downward traction on the fibroid. As already mentioned, we use vulsellums or Lane’s tissue forceps for this, but a myoma screw can also be inserted into the fibroid as demonstrated in Fig. 14.6. The larger the fibroid, the greater care has to be taken to avoid accidental perforation of the uterus and damage to surrounding structures from sharp instruments during morcellation. It is best to take relatively small bites initially and always to cut towards the centre of the fibroid.

Apart from the avoidance of any abdominal incisions, the beauty of this approach to myomectomy, compared with laparoscopic myomectomy for instance, is that the uterus can be repaired much more quickly using conventional instruments and sutures. There is generally surprisingly little bleeding during the surgery, perhaps because traction on the uterus results in kinking of the uterine vessels; we never use vasoconstrictors or other uterotonic agents.

Transvaginal Vaginal Myomectomy via Colpotomy (Adam Magos)

Fibroids which are subserous are not suitable for transcervical myomectomy. In such cases, vaginal myomectomy via an anterior or posterior colpotomy, that is a type 4 vaginal myomectomy, can be considered. Just as the other techniques, this approach was included in textbooks of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century but seemingly abandoned until the 1994 when our Unit reported on 32 out of 35 women managed successfully by transvaginal myomectomy [18]. Since then, there has been a world-wide resurgence of interest in this technique for removing subserous as well as intramural fibroids as evidenced by numerous scientific publications, including not only descriptive series but randomized trials and meta-analyses [19–35]. Although the data is limited, vaginal myomectomy comes out favourably compared with laparoscopic myomectomy.

We prefer to operate via posterior colpotomy as this avoids the need for bladder dissection and also means that the surgery takes place in the relatively larger pelvic basin rather than under the pubic arch. For this reason, if the dominant fibroid is posterior or fundal, we start with a posterior colpotomy, and only if the largest fibroid is anterior do we commence with an anterior colpotomy. On rare occasions, both posterior and anterior colpotomies have to be made (Fig. 14.11).

Fig. 14.11

Posterior or anterior colpotomy is made depending on the site of the dominant fibroid

Having made the colpotomy and entered the peritoneal cavity, the fibroid has to be maneuvered into the incision. This can be technically the most difficult part of the procedure. Hooks, tissue forceps or vulsellums risk tearing the uterus, so our preference is to use a single suture to “walk up” the uterine wall towards the fundus until the fibroid is reached (Fig. 14.12).

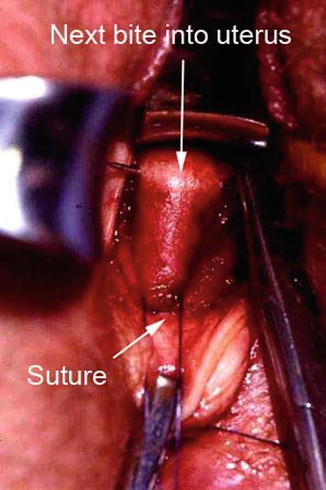

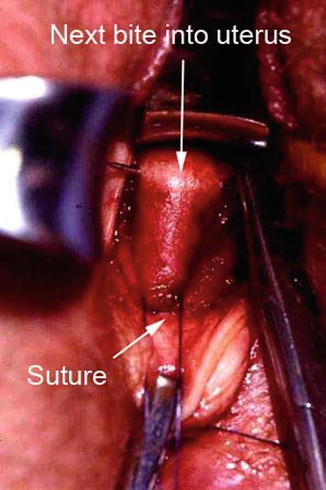

Fig. 14.12

The “walking up” technique to maneuvere the uterus into the colpotomy incision

Depending on the size of the uterus and fibroid(s), it may be possible to pull the uterus through the colpotomy into the vagina, but more often than not, this is not possible, and the myomectomy has to be done through the colpotomy incision. We steady the uterus by placing tissue forceps or sutures into the uterine serosa on either side of a vertical incision over the fibroid (Fig. 14.13). Depending on the size of the fibroid, it is excised with or without morcellation (Figs. 14.14 and 14.15).