Vaginal Hysterectomy

Carl W. Zimmerman

DEFINITIONS

Endopelvic fascia—The layer of fibroelastic connective endopelvic tissue surrounding the bladder, vagina, and rectum. By investing the central pelvic organs in a continuous fashion from the vaginal introitus to the axial skeleton (sacrum), this tissue furnishes suspension to the entire uterovaginal complex and surrounding organs. Division of the paracolpium portion of this continuum is necessary for the completion of a vaginal hysterectomy.

Enterocele—Formed from a separation of the rectovaginal fascia or the pubocervical fascia from the posterior cervix or anterior cervix, respectively. An enterocele is a pelvic hernia that descends through the posterior vaginal fornix or anterior vaginal fornix. The most common location for an enterocele is the posterior superior vaginal segment.

Intramyometrial coring—A surgical technique useful for removal of a large uterus during vaginal hysterectomy. After the uterine vessels have been divided, the myometrium can be circumferentially incised with a scalpel placed parallel to the long axis of the uterus and beneath the serosal covering of the uterus. In effect, coring converts the normal spherical shape of the uterus into an elongated cylindrical or rod shape, enhancing the surgeon’s ability to facilitate uterine removal.

Morcellation—A surgical technique that is useful in reducing the size of an enlarged uterus after the paracolpium and uterine vasculature are ligated. The cervix is divided in a vertical fashion until the enlarged fundus is encountered. At that point, leiomyomata or myometrial segments can be removed using various types of sharp and blunt dissection until the fundus is sufficiently reduced in size to allow completion of extirpation of the organ.

McCall culdoplasty—The most commonly employed technique to reattach the uterosacral ligaments to the posterior vaginal cuff. This technique is useful in posterior enterocele prophylaxis.

The technique of operating through the vagina is a prerogative of the gynecologic surgeon. Vaginal surgery is an essential prerequisite in the cultural and surgical training of a qualified gynecologist. However, in the United States, the most common operation gynecologists perform, the hysterectomy, is predominantly done abdominally or with one of the various endoscopic techniques.

Vaginal hysterectomy is the signature operation of the gynecologic profession. Ample evidence shows that the vaginal approach results in lower morbidity, less pain, more rapid recovery, more rapid return to normal activities, consumption of fewer health care dollars and resources, and a host of other benefits. A gynecologic surgeon should have the ability to perform abdominal, endoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomies. However, vaginal hysterectomy is, and should remain, the hallmark of gynecologic extirpative hysterectomy surgery, and the ability to perform hysterectomy via the vaginal route is a measure of surgical excellence. Vaginal hysterectomy is the “gold standard” for the surgical removal of the uterus because it is minimally invasive when compared to all other routes and techniques. The vaginal route should be considered primary unless a specific contraindication to that approach is recognized. Surgeons’ preference of route is not an indication for avoiding the vaginal approach.

INDICATIONS

With the advent of evidence-based research and outcome studies, several randomized controlled trials have documented the advantages of the vaginal approach to hysterectomy. A 2010 Cochrane review concluded that vaginal hysterectomy, rather than abdominal, should be performed whenever technically feasible to reduce complications, shorten hospital stays, and accelerate the patient’s return to normal activities. Endoscopic approaches were recommended only in those cases where the vaginal approach was not practical. Unfortunately, these clear evidence-based recommendations have not stimulated a change in physician practice patterns. Several authors have addressed the reasons for the continued dominance of the abdominal route for hysterectomy. Johns and colleagues suggested that the route of hysterectomy is usually determined by the skill, experience, and preference of the operating gynecologist. Unfortunately, few other parameters really matter in day-to-day practice. Dorsey and associates stated that the hysterectomy patient is best served by a surgeon who selects the route with which he or she is most confident and comfortable; however, ideal surgical care remains the responsibility of the surgeon. With that in mind, training programs should do whatever is necessary to provide graduates with skill sets that give patients access to evidence-based care. Julian has addressed this concept in detail.

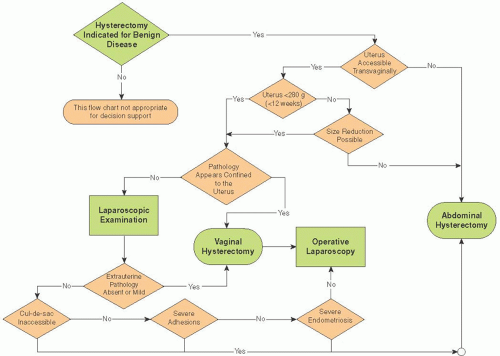

Suggesting that the competency and comfort of the surgeon to perform a vaginal hysterectomy is a requisite to selection of that route may restrict its implementation as a primary technique. Surgeons who prefer to use abdominal or laparoscopic techniques may therefore not choose the route that is most minimally invasive to the patient. Hysterectomy guidelines have been developed in order to identify when abdominal hysterectomy is truly mandated (Fig. 32B.1). Using these guidelines, expert gynecologic surgeons have achieved vaginal hysterectomy rates in excess of 90% without sacrificing quality of care. In contrast, the overall US average for the vaginal approach is approximately 30%, with that figure including laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. More recent data indicate that the advent of robotic techniques will further complicate the selection of hysterectomy route in a way that does not rely on outcome data. In an era of pressure to consume fewer health care dollars, the more expensive abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic approaches continue to flourish despite incontrovertible evidence that vaginal hysterectomy provides as good or better outcomes at less cost.

Vaginal hysterectomy traditionally has been indicated for women with uterine or pelvic organ prolapse, and traditional indications for abdominal hysterectomy have included an

enlarged uterus, prior pelvic surgery, malignancy, and extrauterine disease, such as endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease. We now know that successful vaginal hysterectomy can be done in most of these patients; however, special techniques, such as uterine coring or morcellation, are often helpful, and such ancillary techniques as laparoscopic lymphadenectomy may be required in women with cervical or endometrial cancer. Laparoscopy may also be useful to help evaluate an adnexal mass prior to removal or the extent of endometriosis before completing the surgery with a vaginal hysterectomy and oophorectomy. Laparoscopy may also be used as an aid to reassure and give confidence to the less experienced vaginal surgeon to objectify the pelvic anatomy so that vaginal hysterectomy, in many cases, can be accomplished. With increasing confidence and skill that comes from experience, there are very few patients with indications for hysterectomy in whom the procedure cannot be performed vaginally.

enlarged uterus, prior pelvic surgery, malignancy, and extrauterine disease, such as endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease. We now know that successful vaginal hysterectomy can be done in most of these patients; however, special techniques, such as uterine coring or morcellation, are often helpful, and such ancillary techniques as laparoscopic lymphadenectomy may be required in women with cervical or endometrial cancer. Laparoscopy may also be useful to help evaluate an adnexal mass prior to removal or the extent of endometriosis before completing the surgery with a vaginal hysterectomy and oophorectomy. Laparoscopy may also be used as an aid to reassure and give confidence to the less experienced vaginal surgeon to objectify the pelvic anatomy so that vaginal hysterectomy, in many cases, can be accomplished. With increasing confidence and skill that comes from experience, there are very few patients with indications for hysterectomy in whom the procedure cannot be performed vaginally.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

If the surgeon is concerned about unintentionally injuring the rectum, it may be important for the patient to cleanse the rectum with an electrolyte purgative or a Phospho soda enema given the evening before surgery. Bowel cleansing evacuates solid stool from the rectum, reduces the bacterial load of the intestinal tract, and reduces the incidence of postoperative ileus and constipation.

A single-dose antibiotic as a prophylactic measure, usually a first-generation cephalosporin, should be given within 1 hour before the operation is started. Prophylactic antibiotics have been documented to reduce the risk of postoperative infections. The vaginal pH may be checked at a preoperative visit and prior to prepping the patient. If the pH is elevated above normal (3.8 to 4.2), the normal vaginal ecosystem has been altered. A vaginal pH in the range of 5.0 or greater suggests the potential for bacterial vaginosis and the likelihood that the facultative bacteria normally present in the vagina at concentrations of 103 have reached concentrations of 108. This finding strongly suggests that the vagina is infected before the start of the operation. These patients may not be protected by routine prophylactic antibiotics but may benefit from postoperative therapeutic antibiotics and ideally correction prior to arrival in the operating room. In such patients, consider administration of 500 mg of metronidazole orally twice daily from the second to the seventh postoperative day. This practice reduces the postoperative infection rate following vaginal hysterectomy.

Gynecologists have long believed that a Betadine solution used as a preoperative vaginal scrub will remove most potential pathogens in the vagina, but this has recently been questioned. Some surgeons prep patients with 70% ethanol, even in the vagina, and use a self-adherent surgical drape that covers the rectum and conveniently keeps pubic hair and the labia from interfering with the operative field. Shaving of the pubic hair

is unnecessary, and shaven patients are more uncomfortable postoperatively. Clipping of pubic hair is preferred if hair removal is desired.

is unnecessary, and shaven patients are more uncomfortable postoperatively. Clipping of pubic hair is preferred if hair removal is desired.

Copious lavage of the vaginal vault before, during, and after vaginal hysterectomy may also help to prevent postoperative infections by removing nonadherent bacteria from the vaginal epithelium. Lavage is not used as frequently in the vaginal approach as in other surgical approaches despite the fact that the vagina is a clean contaminated operative field.

The type of stirrups used for the lithotomy position is solely at the discretion of the surgeon. No matter what type is used, careful attention is required to protect vulnerable vascular, bony, and neurologic points in the lower extremities. Some surgeons prefer candy cane-type stirrups. The patient should be positioned with the buttocks at the end of the surgical table or just beyond. The table is placed at a zero horizontal position without Trendelenburg. In this manner, the surgeon can look directly into the vagina without having to look over the weighted speculum. Boot-type stirrups have achieved popularity and may also be used with the patient in the standard lithotomy position. Here, the femur is vertical, and the tibia/ fibula horizontal and oriented toward the contralateral shoulder. Hyperflexion of the femur is discouraged with either type of stirrup. If a procedure lasts more than 4 hours, the risk of neurovascular injury increases. For that reason, every 90 minutes to 2 hours, lowering the legs from the standard lithotomy position into a low lithotomy position for a period of approximately 10 minutes should be considered. Also, final positioning of the patient should protect the patient, allowing the surgeon to operate comfortably, and provide adequate room for surgical assistants to be effective. Assistants need to stand inside the stirrups to see the operative field to both observe and learn the operation. Pneumatic compression stockings are also recommended.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

An examination under anesthesia before initiating the operation to confirm the preoperative findings is recommended in all cases. Undetected pathology may be appreciated during an anesthetized exam along with a more complete assessment of the subtleties of the patient’s anatomy. Placement of a tenaculum for applying traction on the cervix can document the degree of descensus. If more descensus is desired, strong traction on the cervix with vigorous massage of the uterosacral ligaments, especially the left uterosacral ligament, for approximately 30 seconds results in a further descensus of the cervix of approximately 2 to 3 cm.

Although some surgeons prefer to stand during vaginal hysterectomy, others prefer to sit. Assistants to the surgeon should be as comfortable as possible during the operation. The height of the operating table and the surgeon’s chair should be adjusted accordingly. If sitting, an instrument tray may be placed on the surgeon’s lap, making it easier to have access to the desired instruments during the operation. The number of instruments used during vaginal surgery should be kept at a minimum to prevent instruments from obscuring the surgeon’s vision.

Catheterization of the bladder before the initiation of vaginal hysterectomy is performed at the preference of the surgeon. Sometimes, it is easier to identify unintentional cystotomy when the bladder is moderately distended (approximately 200 mL) with urine, dyed fluid, or sterile infant milk. If the bladder becomes too distended, catheter drainage of the bladder may improve the visibility within the restricted operative space. If a cystotomy occurs, it is usually best to complete the vaginal hysterectomy before proceeding with repair of the bladder. In many cases, the cystotomy may make the bladder dissection easier because now, the location of the bladder is clear and the correct plane of dissection is more easily visualized. Sometimes, a finger in the bladder may also facilitate a difficult vesicocervical or vesicouterine dissection. The bladder must be mobilized adequately around the area of operative injury so that the surgeon can completely evaluate the extent of the cystotomy and be certain that the repair is completed without excess tension on the injured site.

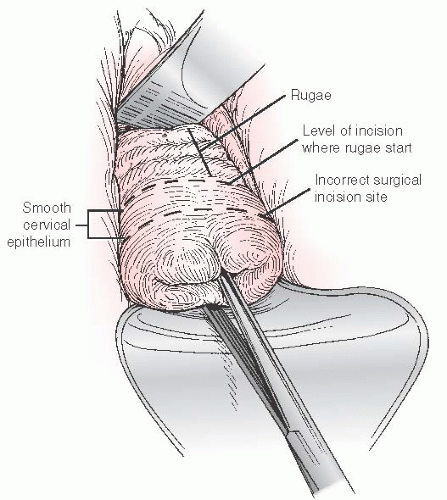

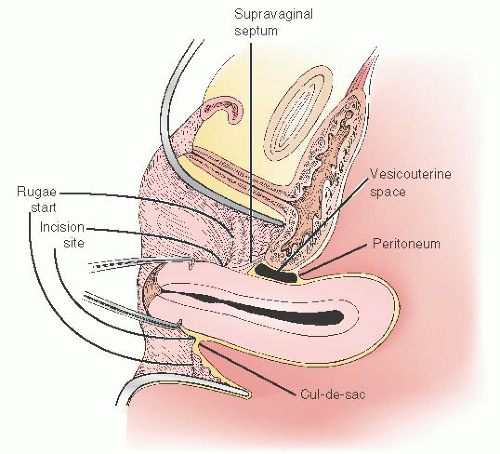

The initial anterior vaginal incision should be made through the full thickness of the vaginal epithelium at the border of the vaginal rugae and the smooth epithelium covering the cervix (Fig. 32B.2). An initial circumscribing cervical incision made on the cervix at the junction of rugae and smooth epithelium preserves vaginal length and helps avoid unintentional entry into the bladder anteriorly and rectum posteriorly. In addition, an incision at the point where the vaginal rugae begin to reflect away from the smooth epithelium of the cervix appropriately places the epithelial incision closer to the point of entry into the posterior and anterior peritoneum (Fig. 32B.3). An incision in this location allows the surgeon to avoid excessive dissection of the connective tissues between the vagina and the peritoneum, reduces blood loss from cervical artery branches, shortens operative time, and facilitates identification of the peritoneal entry points.

Julian has reported on the benefit of infiltrating the vaginal wall with a mixture of 1:200,000 epinephrine diluted in normal saline to control small blood vessel bleeding from the vagina. However, in our experience, oozing from the incised

vaginal epithelium rarely results in significant blood loss when the incision is made where the vaginal rugae start. If oozing from the incised edges of the vagina becomes a problem, it is easy to control with electrocautery.

vaginal epithelium rarely results in significant blood loss when the incision is made where the vaginal rugae start. If oozing from the incised edges of the vagina becomes a problem, it is easy to control with electrocautery.

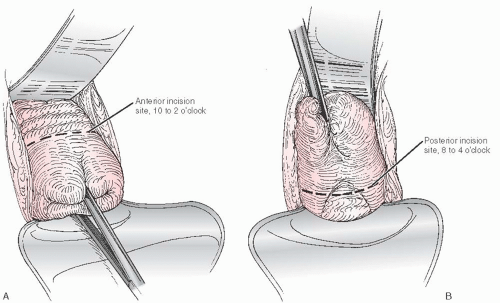

At the beginning of the operation, when the cervix is still within the vagina, a circumscribing incision around the cervix is difficult to perform with a scalpel or electrocautery instrument because it is difficult to maintain either device perpendicular to the circumscribing vaginal incision. This issue is not a concern when the cervix protrudes from the vagina. However, when the cervix cannot be brought out of the vagina with traction, the initial incision should be made on the anterior vaginal wall from approximately the 10- to 2-o’clock position and on the posterior vaginal wall between the 8- and 4-o’clock positions. These incisions provide adequate space for transection of the paracolpium allowing the cervix to descend for subsequent entry into the posterior and anterior peritoneum and ligation of the uterine vasculature at the appropriate time (Fig. 32B.4A, B).

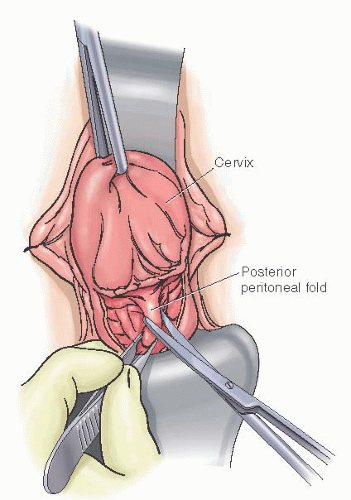

After completing the vaginal incisions, the cervical tenaculum is replaced on the posterior lip of the cervix with taut traction of the cervix achieved by elevating the tenaculum anteriorly. If the posterior incision in the vagina is placed at the appropriate level where rugae are not present and at the point where the uterosacral ligaments join the cervix, the posterior cul-de-sac and peritoneum can readily be identified with an Allis clamp or tissue forceps. This step is facilitated by putting the vaginal epithelium and accompanying peritoneum on stretch as the peritoneum bulges outward

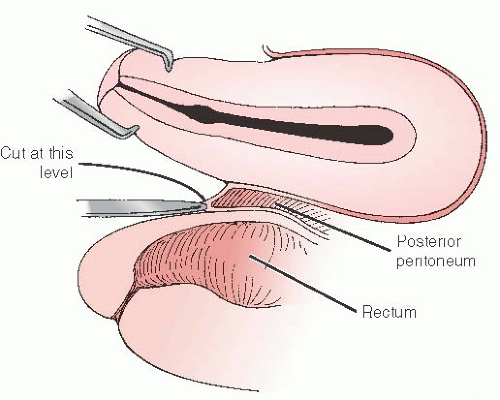

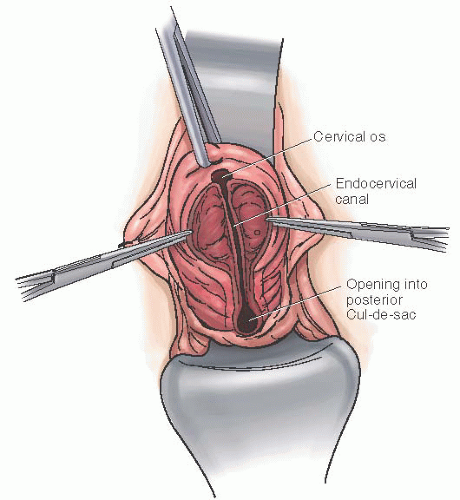

toward the surgeon (Fig. 32B.5). The importance of properly performing this step cannot be overstated. Entry into the posterior peritoneum is best accomplished by an incision directly above the tissue forceps that grasps the outward U-shaped bulge of the peritoneal fold (Fig. 32B.6). If the incision is placed closer to the cervix in an attempt to prevent injury to the rectum, the dissection often proceeds into the posterior cervical stroma. Unfortunately, an incision placed nearer to the cervix frequently results in a retroperitoneal dissection, which continues in this plane and ultimately pushes the peritoneum superiorly and posteriorly, obscuring identification of the peritoneum and frustrating the surgeon. Should this occur, the posterior lip of the cervix and vagina can be cut in a vertical direction that exposes the peritoneum at a higher level so it can be recognized and entered directly. This procedure is a cervicocolpotomy (Fig. 32B.7).

toward the surgeon (Fig. 32B.5). The importance of properly performing this step cannot be overstated. Entry into the posterior peritoneum is best accomplished by an incision directly above the tissue forceps that grasps the outward U-shaped bulge of the peritoneal fold (Fig. 32B.6). If the incision is placed closer to the cervix in an attempt to prevent injury to the rectum, the dissection often proceeds into the posterior cervical stroma. Unfortunately, an incision placed nearer to the cervix frequently results in a retroperitoneal dissection, which continues in this plane and ultimately pushes the peritoneum superiorly and posteriorly, obscuring identification of the peritoneum and frustrating the surgeon. Should this occur, the posterior lip of the cervix and vagina can be cut in a vertical direction that exposes the peritoneum at a higher level so it can be recognized and entered directly. This procedure is a cervicocolpotomy (Fig. 32B.7).

The posterior peritoneum is then opened with curved scissors, and a long-bladed Steiner Auvard weighted speculum is introduced into the posterior peritoneal cavity. Examination of the cul-de-sac can reveal further pathology, for example, endometriosis, leiomyomata, or adnexal pathology—that may need to be addressed later in the operation. Identification of the uterosacral ligaments by palpation can be accomplished during examination of the cul-de-sac by placing a digit medial to the ligament and identifying the rectouterine fold through the posterior colpotomy incision.

Oozing of blood from the posterior incision between the vagina and peritoneum may occur. Placement of a weighted speculum into the posterior peritoneal cavity will compress

most bleeding points in this area until completion of the surgery and cuff closure. If the vaginal epithelium has not been completely circumscribed, once posterior dissection has been developed, the vaginal epithelial incision should be completed by connecting the previous anterior and posterior incisions before the supportive ligaments of the uterus can be clamped.

most bleeding points in this area until completion of the surgery and cuff closure. If the vaginal epithelium has not been completely circumscribed, once posterior dissection has been developed, the vaginal epithelial incision should be completed by connecting the previous anterior and posterior incisions before the supportive ligaments of the uterus can be clamped.

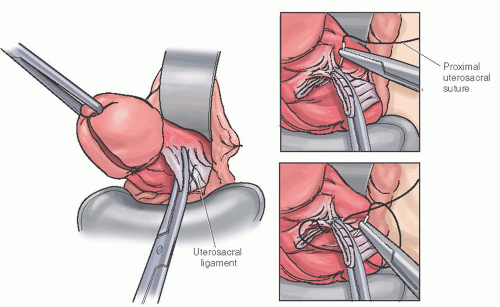

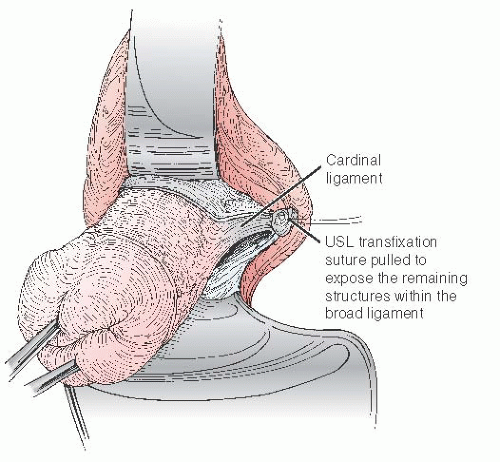

Transection of the uterosacral ligaments is the single most important step in successfully completing a vaginal hysterectomy. The uterosacral ligament pedicle should be completed by placing the medial jaw of the clamp within the rectouterine fold while holding the clamp vertical and not try to swing around the cervix in a more horizontal plane. The medial tip of each clamp should be placed within the peritoneal cavity in the rectouterine fold and the lateral tip around the outside of the ligament. Special hysterectomy clamps have been developed to improve on the traditional Heaney clamp (Fig. 32B.8A-C). After transection of the pedicle, rotating the handles of the clamp laterally and superiorly facilitates suturing at the tip of the clamp. This rotation brings the tip of the clamp into full view and exposes a triangular area beneath the clamp for easier retrieval of the needle. Placement of a double clamp for uterine supportive or vascular structures is not necessary. Each uterosacral ligament should be secured by a transfixation suture to the posterolateral surface of the vagina and tied behind the clamp at about the 4- and 8-o’clock positions. Lateral traction on this suture provides the best exposure to the remaining structures that need to be transected to complete hysterectomy (Fig. 32B.9). This traction and the use of large hysterectomy clamps largely replace the need for lateral retractors in the vagina. Clamping and tagging the uterosacral ligaments separately allows for their identification, later use in cuff repair, and, if desired, a McCall culdoplasty at the end of the procedure. The uterosacral ligament pedicle is the only one that needs to be tagged during a vaginal hysterectomy and the only one that may safely be placed under traction.

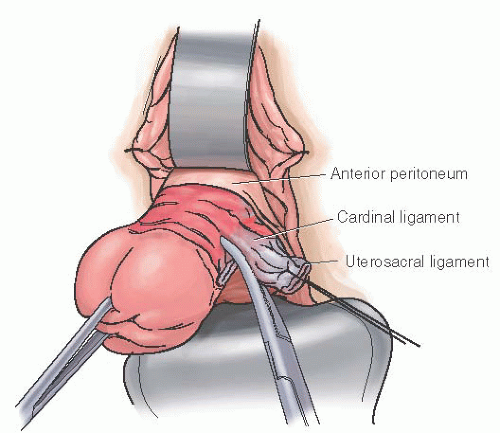

After making sure the tips of the clamps are within the posterior peritoneal cavity, the cardinal and pubocervical (bladder pillar) ligaments are clamped by placing a clamp horizontally

and clamping from the apex of the uterosacral pedicle to a point on the anterior cervix medial to the bladder pillar encompassing all the remaining connective tissue of the paracolpium (Fig. 32B.10). If already entered, the anterior peritoneum should not be pulled into this clamp at this point of the operation. A complete anterior dissection is needed to safely complete this pedicle. Bringing the anterior and posterior peritoneal edges together should only be accomplished with the uterine artery pedicle as this maneuver serves to seal off the broad ligament and effectively prevents bleeding from the vascular plexus located within the leaves of the broad ligament. Because the anterior peritoneum usually begins at the level of the uterine vessels, there is not enough peritoneal mobility to bring both the anterior and posterior peritoneal surfaces together at the level of the cardinal ligaments. Therefore, to be certain that the surgeon can seal both leaves of the broad ligament together with the uterine artery, it is best to avoid any attempt to bring the peritoneal edges together when the uterosacral or cardinal ligament is clamped. A simple suture ligature first at the tip and then around the end of the clamp is usually sufficient for hemostasis of the cardinal ligament without the need for transfixation. This suture ligature is not tagged or held.

and clamping from the apex of the uterosacral pedicle to a point on the anterior cervix medial to the bladder pillar encompassing all the remaining connective tissue of the paracolpium (Fig. 32B.10). If already entered, the anterior peritoneum should not be pulled into this clamp at this point of the operation. A complete anterior dissection is needed to safely complete this pedicle. Bringing the anterior and posterior peritoneal edges together should only be accomplished with the uterine artery pedicle as this maneuver serves to seal off the broad ligament and effectively prevents bleeding from the vascular plexus located within the leaves of the broad ligament. Because the anterior peritoneum usually begins at the level of the uterine vessels, there is not enough peritoneal mobility to bring both the anterior and posterior peritoneal surfaces together at the level of the cardinal ligaments. Therefore, to be certain that the surgeon can seal both leaves of the broad ligament together with the uterine artery, it is best to avoid any attempt to bring the peritoneal edges together when the uterosacral or cardinal ligament is clamped. A simple suture ligature first at the tip and then around the end of the clamp is usually sufficient for hemostasis of the cardinal ligament without the need for transfixation. This suture ligature is not tagged or held.

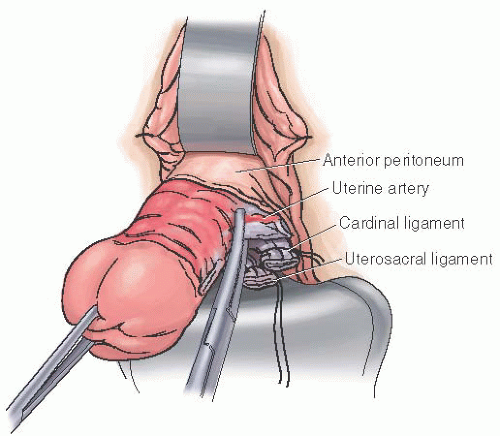

If exposure is good, the uterine arteries may be clamped, divided, and ligated at the point before entering the peritoneum anteriorly under the bladder. They are best clamped in their entirety and under direct visualization. In contrast to the uterosacral and cardinal/pubocervical clamps that are placed perpendicular to the body of the cervix, the uterine artery clamp is placed parallel to the long axis of the uterus as the tip of the clamp secures the uterine artery as it bifurcates into ascending and descending branches (Fig. 32B.11). As traction is placed on the uterus when the artery is cut, there is a definite sensation that the uterus descends signifying that the entire uterine vascular bundle has been transected, including the ascending and descending branches. If descent of the uterus is not noted, often an additional portion of the uterine artery remains and must be secured with another clamp. A single well-tied suture is all that is required for the uterine artery pedicle. Limiting the tissue within the clamp to the vascular bundle helps to make the pedicle manageable and the suture ligature more secure. Many surgeons try to include middle portions of the broad ligament with the uterine artery because they feel a need to place clamps on the remaining portions of the broad ligament as they proceed up on each side of the uterus.

Complete development by dissection of the vesicocervical and vesicouterine spaces is a prerequisite to identifying and opening the anterior peritoneum. This step is perceived to be the most difficult portion of the vaginal hysterectomy procedure. Adequate exposure, by division of the paracolpium and full dissection of the anterior avascular spaces, makes this key step of hysterectomy much easier to complete.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree