Fig. 4.1

Uterine sonography showing, on the left, an intramural fibroid and, on the right, a pedunculated fibroid

Risk Factors

Although selection bias may limit current epidemiologic studies, a number of factors associated with an increased risk of fibroids have been determined. Increasing age is associated with an increased incidence of fibroids: 4.3 per 1,000 woman-years for 25–29 year-olds; 22.5 for 40–44 year-olds [6].

African-American women have an almost three times greater risk of having fibroids than Caucasian women, unrelated to other known risk factors [7].

African-American women also have fibroids develop at a younger age, and have more numerous, larger and more symptomatic fibroids [8]. First degree relatives of women with fibroids have a 2.5 times increased risk of developing fibroids [9].

Greater exposure to endogenous hormones, as found with early menarche (<10 years old) increases, and late menarche decreases, the risk of having uterine fibroids [10]. Fibroids are also smaller and less numerous in hysterectomy specimens (Fig. 4.2) from postmenopausal women, when endogenous estrogen levels are low [11].

Fig. 4.2

Photo of uterus removed via colpohysterectomy with opening of the anterior uterine wall and a single fibroid appearing

Factors that increase overall lifetime exposure to estrogen, such as obesity, increase the incidence. Decreased exposure to estrogen found with smoking, exercise, and increased parity is protective [12].

In women with and without clinically detectable fibroids, serum levels of estrogen and progesterone are similar. However, aromatase within fibroids leads to denovo production of estradiol with higher levels than in normal myometrium. Fibroids have increased concentrations of progesterone receptors A and B compared with normal myometrium and the highest mitotic counts in fibroids are found at peak progesterone production, suggesting that progesterone influences fibroid growth [13–15].

Oral contraceptives do not increase the presence or growth of fibroids (Fig. 4.3) [16].

Fig. 4.3

A gynecological consultation of a patient worried to have uterine fibroids, after taking the oral contraceptive for a long time

One study found an increased risk of fibroids with oral contraceptives [17], but a subsequent study found no increased risk with use or duration of use [18].

Although another study found a decreased risk [19], women with known fibroids may be prescribed oral contraceptives less frequently, leading to selection bias [20].

For the majority of postmenopausal women with fibroids, hormone therapy will not stimulate fibroid growth (Fig. 4.4).

Fig. 4.4

A postmenopausal women assuming hormone replacement therapy in pills or in patch: they will not stimulate fibroid growth

If fibroids do grow, the progesterone is likely to be the cause (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5

A woman assuming progestins by oral pills: they can stimulate fibroid growth

Among postmenopausal women with fibroids given 2 mg of oral estradiol and 2.5 or 5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) daily for 1 year, 77 % percent of women on the lower dose of MPA had either no change or a decrease in fibroids diameters while 50 % of women taking 5 mg MPA had an increase in fibroid size [21].

Postmenopausal women with known fibroids, followed with sonography for 12 months, were noted to have an average 0.5 cm increase in the diameter of fibroid after using transdermal estrogen patches plus oral progesterone, but women taking oral estrogen and progesterone had no increase in size [22].

Increasing parity decreases the incidence and number of clinically apparent fibroids [23–25]. The remodeling of the postpartum myometrium, including apoptosis and dedifferentiation, may lead to involution of fibroids [26].

Alternatively, vessels supplying fibroids (Fig. 4.6) may regress during post-partum involution, depriving fibroids of their source of nutrition [27].

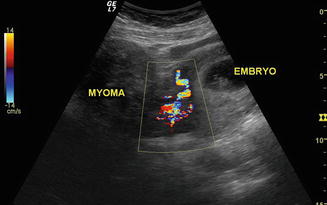

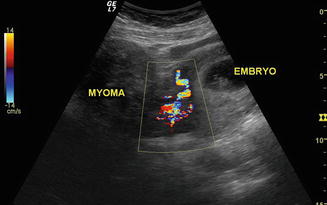

Fig. 4.6

Uterine sonography in early pregnancy showing, on the left, a uterine pedunculated myoma and, on the right, uterus with embryo

Obesity increases conversion of adrenal androgens to estrone and decreases sex hormone binding globulin, with an increase in biologically available estrogen. The risk of fibroids increases 21 % with each 10 kg increase in body weight, with increasing BMI and with greater than 30 % body fat. Few studies have examined the association between diet and the presence or growth of fibroids. One study found that red meat and ham increased the incidence of fibroids, while green vegetables decreased this risk, however, calorie and fat intake were not measured [28].

Women in the highest category of physical activity (approximately 7 h/week) were significantly less likely to have fibroids than women in the lowest category (<2 h/week) [29].

Clinical Presentation

Fibroids can cause morbidity and affect quality-of-life; women having hysterectomies due to fibroid-related symptoms (Fig. 4.7) have significantly worse scores on SF-36 quality-of-life questionnaires than women with hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease or arthritis [32].

Fig. 4.7

A large fibroid uterus

Because the association of fibroids with heavy menstrual bleeding has not been clearly established, it is important to consider other possible etiologies including coagulopathies such as von Willebrandt’s disease [33].

One study found that women with fibroids used 7.5 pads or tampons on the heaviest day of bleeding compared with 6.1 pads or tampons used by women without fibroids. Women with fibroids larger than 5 cm (Fig. 4.8) had slightly more gushing and used about three more pads or tampons on the heaviest day of bleeding than women with smaller fibroids [34].

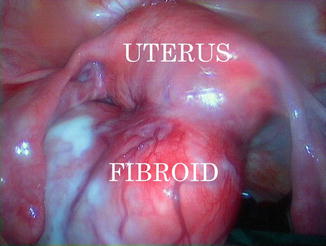

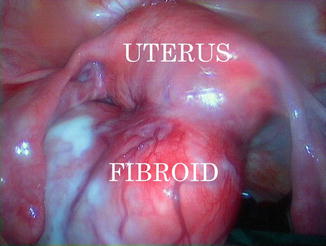

Fig. 4.8

A laparoscopic image of a non pregnant uterus with a posterior pedunculated fibroid of 8 cm of diameter

A recent study reported that 259 women found to have submucous fibroids on hysteroscopic examination had objective measures of heavy menstrual bleeding, i.e., lower hemoglobin levels and a higher risk of anemia than women without submucous fibroids, although self-reported pictorial blood loss assessment did not differ. Women with fibroids are only slightly more likely to experience pelvic pain than women without fibroids. In one study, 96 women found to have fibroids based on trans-vaginal sonography reported moderate or severe dyspareunia or non-cyclic pelvic pain only slightly more than women without fibroids; there was no difference in moderate or severe dysmenorrhea. A study of 827 women with ultrasound detected fibroids found that deep dyspareunia was related to fibroids and the relationship was even stronger for “severe deep dyspareunia” [35].

However, women who present to gynecologists for evaluation with fibroid-associated pain may be different than those in the general population. As fibroids enlarge, they may outgrow their blood supply with resulting cell death and degeneration. The type of degeneration, as hyaline, cystic, or hemorrhagic (Fig. 4.9), appears to be unrelated to the clinical symptoms [36]. Rarely, torsion of a pedunculated subserosal fibroid may occur and produce acute pelvic pain that requires surgical intervention [37].

Fig. 4.9

A surgical image of a large myomatosic uterus on the left; on the right, the image shows a large fibroid in necrotic degeneration (with blood supply minimizing and resulting cell death and degeneration)

Fibroids cause urinary symptoms, although few studies have examined this association. Following uterine artery embolization and a 35 % reduction in mean uterine volume, 68 % of women had great or moderate improvement in frequency and urgency [38].

Likewise, a 55 % decrease in uterine volume following 6 month treatment with GnRH-a lead to a decrease in urinary frequency, nocturia and urgency [39].

There were no changes in urge or stress incontinence as measured by symptoms or urodynamic studies. These findings may be related to decrease in uterine volume or other effects of GnRH treatment.

Natural History of Fibroids

Predicting fibroid growth is not possible. Serial MRIs from 72 premenopausal women with fibroids found a median growth rate over 1 year of 9 % although 7 % of fibroids got smaller over the study period. The range of growth and shrinkage was very large: −89 to +138 % [6].

Small fibroids (<5 cm) had more frequent growth spurts than did larger fibroids. Surprisingly, multiple fibroids found in the same woman showed very variable growth rates, suggesting that a woman’s hormone levels do not determine the rate of growth. After age 35, growth rates did not decline with age for black women, but did decline in white women. In premenopausal women, “rapid uterine growth” almost never indicates presence of uterine sarcoma (Fig. 4.10). One study found only 1 sarcoma among 371 (0.26 %) women operated on for rapid growth of presumed fibroids [40]. No sarcomas were found in the 198 women who had a 6 week increase in uterine size over 1 year, one published definition of rapid growth. Women found to have uterine sarcoma are often clinically suspected of having a pelvic malignancy [41]. Between 1989 and 1999, the SEER database reported 2,098 women with uterine sarcomas with an average age of 63 years [42].

Fig. 4.10

A premenopausal women operated of abdominal hysterectomy for “rapid uterine growth”: on the top left, the uterus with a fundal large fibroid; on the right, the angiographic image shows an hypervascularization of fibroids, with large supplying blood vessels; on the lower left, the single fibroid enucleated by pathologist

Genetic differences between fibroids and leiomyosarcomas indicate that leiomyosarcomas do not result from malignant degeneration of fibroids and comparative genomic hybridization did not find specific anomalies shared by fibroids and leiomyosarcomas [43].

In that fibroid growth is not predictable, women with fibroids who are mildly or moderately symptomatic, may choose to defer treatment. As women approach menopause and there is limited time to develop new symptoms, “watchful waiting” may be considered. There is no evidence that not having treatment for fibroids results in harm, except for women with severe anemia from fibroid-related heavy menstrual bleeding or hydronephrosis due to obstruction of the ureter(s) from an enlarged fibroid uterus (Fig. 4.11).

Fig. 4.11

An image of removed uterus by women with severe anemia: it shows an enlarged fibroid uterus, with related heavy menstrual bleeding and hydronephrosis due to obstruction of the left ureter

After 1 year of “watchful waiting”, 77 % of women with uterine size 8 weeks or greater had no significant changes in the self-reported amount of bleeding, pain or degree of bothersome symptoms [44].

However, of the 106 women who initially chose “watchful waiting”, 23 % opted for hysterectomy during the course of the year.

Diagnosis

Assessing uterine size by bimanual examination correlates well with uterine size and weight at pathological examination, even for most women with BMI >30 [45].

Transvaginal sonography (TVS) (Fig. 4.12), saline-infusion sonography (SIS), hysteroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can all be used to diagnose fibroids. An excellent study used all of these modalities on 106 women and the findings were compared to pathologic assessment following hysterectomy [46].

Fig. 4.12

A transvaginal ultrasonography showing a myomatosic uterus

Submucous fibroids were best identified with MRI (100 % sensitivity, 91 % specificity); next best was saline-infusion sonography (sensitivity, 90 % specificity, 89 %) followed by transvaginal sonography (sensitivity, 83 %, specificity, 90 %) and hysteroscopy (sensitivity, 82 % specificity, 87 %). Sonography is the most readily available and least costly imaging technique to differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology and is reasonably reliable for evaluation of uterine volume <375 cc. and containing four or fewer fibroids [47].

MRI is not operator-dependent and has low inter-observer variability for diagnosis of submucous fibroids, intramural fibroids and adenomyosis when compared with TVS, SIS and hysteroscopy [47, 48].

MRI allows evaluation of the number, sizes and positions of submucous, intramural and subserosal fibroids and can evaluate their proximity to the bladder, rectum and endometrial cavity. MRI helps define what can be expected at surgery, and might help the surgeon avoid missing fibroids during surgery [49].

The preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma using dynamic (timed) MRI with gadolinium may be possible. Diagnosis with total serum LDH, LDH isoenzyme 3 and gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MRI (Gd-DTPA) has been reported to be highly accurate [50].

T1 images should be taken during the arterial phase, between 40 and 60 s after infusion of Gd. Since sarcomas have increased vascularity, they are expected to show increased enhancement with Gadolinium while degenerating fibroids have decreased perfusion and decreased enhancement. Using this protocol in 87 women with fibroids, 10 with leiomyosarcomas and 130 with degenerating fibroids, the authors reported 100 % specificity, 100 % positive predictive value, 100 % negative predictive value and 100 % diagnostic accuracy for leiomyosarcoma. Further investigation of this protocol should be performed to confirm this accuracy.

Treating Pre-operative Anemia

In women with significant pre-operative anemia, intravenous iron can be used to increase hemoglobin levels. A randomized study of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and Hb levels <9.0 g/dl who were scheduled to have surgery received either intravenously iron or oral iron and the mean increase in hemoglobin was higher in the intravenous iron group (3.0 vs. 0.8 g/dl). There were no severe adverse events in either group [51].

Epoetin, a recombinant form of erythropoietin, 250 IU/kg (approximately 15,000 U) per week for 3 weeks prior to elective surgery increased hemoglobin concentrations by 1.6 g/dl and reduce transfusion rates when compared to controls [52].

Also, a study of women with fibroids and mean hemoglobin concentrations of 10.2 g found that after 12 weeks, 74 % of the women treated with GnRH-a and iron had hemoglobins greater than 12 g. compared with 46 % of the women treated with iron alone [53].

New Appearance of Fibroids

Fibroids do not recur; once a fibroid is removed it does not grow back. While new fibroids may arise over time (new appearance), most women will not require additional treatment. If a myomectomy is performed in the presence of a single fibroid (Fig. 4.13), only 11 % of women will need subsequent surgery [54].

Fig. 4.13

A laparoscopic single myomectomy: (a) incision of uterine serosa till the uterine fibroid; (b) enucleation of fibroid from its pseudocapsule; (c) fibroid traction by a surgical drill; (d) fibroid enucleation from uterus

If three or more fibroids are removed, only 26 % will need subsequent surgery (mean follow-up 7.6 years). Incomplete follow-up, insufficient length of follow-up, the use of either trans-abdominal or transvaginal sonography (with different sensitivity), detection of very small, clinically insignificant fibroids, or use of calculations other than life-table analysis confound many studies of new fibroid appearance [38].

Patient symptom questionnaires have a reasonably good correlation with sonographic or pathologic confirmation of significant fibroids and may be the most appropriate method of gauging clinical evidence of new fibroids [7].

One study of 622 patients followed over 14 years, found new appearance of fibroids discovered with clinical examination and confirmed by ultrasound was 27 % [55]. Ultrasound is sensitive, but detects clinically insignificant fibroids (Fig. 4.14).

Fig. 4.14

Ultrasound examination is a sensitive instrumental method of fibroids’ diagnosis, but often occasionally detects clinically insignificant fibroids

Women followed after abdominal myomectomy using clinical evaluation every year and transvaginal sonography at 2 and 5 years found the probability of new appearance by 5 years was 51 % [56]. However, no lower size limit was used for the sonographic diagnosis of fibroids, and this study found many clinically insignificant fibroids. Only 15 % of women with a normal sonogram following an abdominal myomectomy had new fibroids larger than 2 cm, detected over 3 years [57].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree