Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder

INTRODUCTION

Transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD) is a unique clonal proliferation of megakaryocytic precursors that is clinically indistinguishable from congenital leukemia and is seen almost exclusively in neonates with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).1 TMD is typically characterized by the presence of leukocytosis and circulating blast cells in the blood of an otherwise healthy-appearing newborn. These blast cells will generally resolve spontaneously by 3–6 months of age without any specific interventions.2 However, approximately 20% of patients will present with severe hydrops, organomegaly, hepatic fibrosis, and other life-threatening complications, with an associated mortality rate approaching 45% at 3 years.3

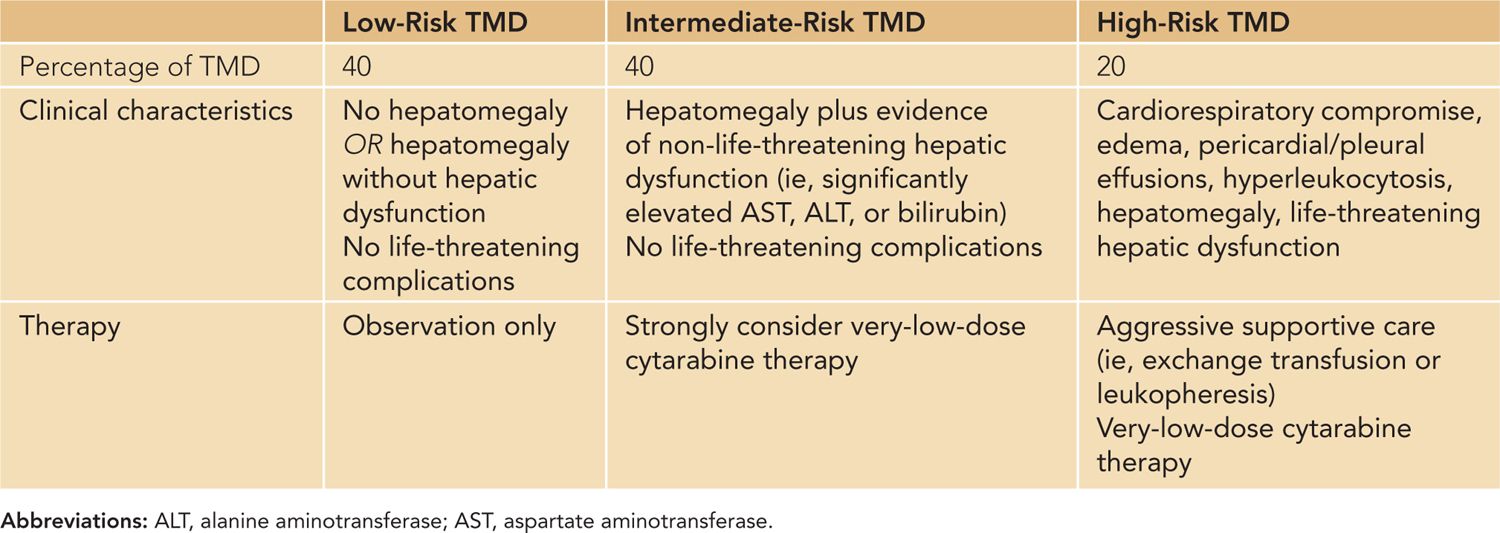

Because of their clinical heterogeneity, patients with TMD have been classified into 3 distinct groups: high risk, intermediate risk, and low risk4 (Table 94-1). High-risk patients with TMD (20%) include those with severe life-threatening complications, such as cardiorespiratory compromise, hyperleukocytosis (white blood cells [WBCs] > 100 × 103/µL) and liver failure (with attendant cholestasis, ascites, or disseminated intravascular coagulation [DIC]). The intermediate-risk patients (40%) include infants with hepatomegaly and hepatic dysfunction but no acute life-threatening complications. Interestingly, although these patients rarely die from acute TMD-related complications, they still have an overall mortality of 23% at 3 years. In contrast, the low-risk patients (40%) experience an 8% overall mortality at 3 years.

Table 94-1 Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD) Risk Groups

Approximately 10%–20% of newborns with Down syndrome with TMD develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) within the first 2 years of life.1 This leukemia most commonly takes the form of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) and can be traced to the patient’s original TMD by unique genetic markers (ie, GATA1 mutations).5–7

CLINICAL FINDINGS

History and Physical

The patient with “classic” TMD is an otherwise healthy-appearing infant with physical characteristics suggestive of trisomy 21 (eg, epicanthal folds, hypotonia, single palmar crease). However, as discussed, patients with higher-risk TMD may present with cardiorespiratory compromise caused by severe hydrops (with concomitant edema, pericardial/pleural effusions, ascites) or marked hepatosplenomegaly. Patients may also present with signs and symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome secondary to hyperleukocytosis, with attendant thrombotic complications. These symptoms may include respiratory distress, apnea, lethargy, irritability, seizures, or other stroke-like symptoms. More recently, an association with a vesiculopustular rash that typically appears on the face has been reported, although the exact relationship with TMD remains unclear.8–10 Finally, it should be noted that patients any of the physical characteristics of Down syndrome but may present only with TMD.11,12 Therefore, the presence of proliferating blasts in a neonate without obvious signs of trisomy 21 should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of mosaic trisomy 21.

Laboratory Testing

All infants with either a prenatal diagnosis of or physical characteristics consistent with trisomy 21 should have a screening complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential within the first 24 hours of life. TMD is usually diagnosed by the presence of circulating blast cells on a blood smear in conjunction with leukocytosis, although the range of WBC values can be broad (4.6–259 × 103/µL, with a median value of 32.8 × 10 3/µL).4 Hepatic dysfunction, as evidenced by elevated liver transaminases, bilirubin, or prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), is an important component of risk stratification and can be a potentially life-threatening complication. Tumor lysis laboratory values (potassium, creatinine, phosphate, calcium, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], uric acid) should also be monitored, especially in patients with markedly elevated WBC counts. Additional laboratory testing is generally not necessary in classic TMD, but flow cytometry and cytogenetics may be required for atypical presentations.

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree