Background

Women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) commonly undergo induction of labor (IOL) at term, but the risks and benefits of IOL are incompletely understood.

Objective

We examined the relationship among gestational age, IOL, and the rate of cesarean delivery (CD) in women with GDM.

Study Design

We identified 863 women with GDM who underwent either IOL or spontaneous labor ≥37 0/7 weeks. Demographic, cervical favorability, and outcome data were abstracted from the medical record. We compared the CD rate in women undergoing IOL at each week of gestation with expectant management to a later gestational age.

Results

When compared to women who were expectantly managed, IOL at 37 weeks (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.53; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76–3.06; P = .23), 38 weeks (aOR, 2.07; 95% CI, 0.89–4.80; P = .09), and 39 weeks (aOR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.44–1.42; P = .43)) was associated with similar risk for CD as expectant management after adjustment for nulliparity, body mass index, baseline simplified Bishop score, and maternal age. CD rates were higher in nulliparous women, but did not differ significantly in those undergoing IOL or expectant management. In multiparous women, IOL was significantly associated with an increased risk for CD at 38 weeks (aOR, 7.47; 95% CI, 1.6–34.8; P = .01) and rates of CD (17.39% vs 2.2%, P = .001) were significantly higher in multiparous women with an unfavorable Bishop score induced <39 weeks. Neonatal morbidity was similar across gestational ages after adjustment for maternal body mass index and maternal glycemic control.

Conclusion

IOL results in similar risk for CD as expectant management between 37-40 weeks of gestation. Rates of CD differed based on cervical exam and parity. These findings suggest that gestational age alone does not significantly impact maternal and neonatal outcomes, but that decisions regarding delivery in women with GDM should take into account cervical exam and parity.

Introduction

Pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are at increased risk for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes including macrosomia and birth trauma, and for these reasons women with GDM frequently undergo induction of labor (IOL) at term in the hope that maternal and fetal risks with continued gestation can be minimized. Decisions regarding delivery planning are important, because the cesarean delivery (CD) rate has risen to a recent high of 32%, increasing >50% in the last decade. Rates of IOL have also increased in parallel, now affecting 23% of all births.

The association between IOL and CD is complex. Early studies that compared women who undergo IOL to those who experience spontaneous labor at the same gestational age found that IOL was associated with increased risk for CD. However, physicians can never chose between spontaneous or induced labor at any given gestational age, and results from studies comparing IOL to expectant management are mixed, with some studies demonstrating a decreased rate of CD, and others an increased risk for CD. An unfavorable Bishop score at the time of IOL may be associated with an increased risk for CD, but the largest studies have been unable to account for this important covariate. In addition, recent data in women with hypertensives disorders of pregnancy suggest that women with an unfavorable cervix have the greatest benefit from IOL.

Optimal delivery timing in women with GDM remains controversial. Observational studies have suggested that IOL >38 weeks’ gestation in women with GDM might reduce the risk of macrosomia and shoulder dystocia, but the impact of IOL on risk for CD was mixed and neonatal outcomes were not assessed in all studies. A single randomized controlled trial that included patients treated with insulin demonstrated a lower rate of large-for-gestational-age cases with IOL at 38 weeks compared to expectant management with no increased risk of CD, shoulder dystocia, or neonatal complications, but these results may not be generalizable to all women with GDM given the inclusion of women with pre-GDM and only those treated with insulin. In addition, a recent study of women with GDM found no increased risk for CD in women undergoing IOL ≤40 weeks of gestation, but the authors were unable to account for cervical exam at the time of delivery, and some GDM diagnoses were blinded to patients and providers. The goal of this analysis was to examine the relationship among gestational age, IOL, and the rate of CD in women with GDM while accounting for cervical exam and parity. We hypothesized that delivery at 39 weeks would optimize maternal and neonatal outcomes irrespective of maternal cervical exam.

Materials and Methods

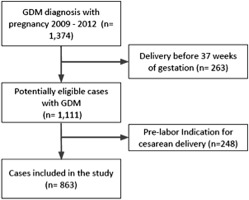

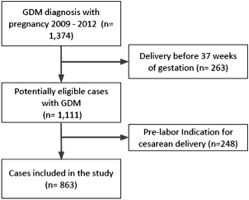

This was a retrospective cohort study of women with singleton gestations and GDM who were delivered at Magee-Womens Hospital (University of Pittsburgh, PA) from January 2009 through October 2012. Briefly, the cohort included 1374 women who were diagnosed with GDM if they had either a 50-g, 1-hour glucose challenge test >200 mg/dL, or if they had ≥2 abnormal values on a 100-g, 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test as defined by the criteria of Carpenter and Coustan. For each subject, we included only the first pregnancy during the study period. Women with a prelabor indication for cesarean were excluded from this analysis. To examine the relationship among gestational age, IOL, and the rate of CD in women with GDM, this analysis focused on the 863 women (62.8% of the overall cohort) with either IOL or spontaneous labor ≥37 0/7 weeks ( Figure 1 ). Women included in the study received prenatal care in the maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics clinics at our hospital. Regulatory approval was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was not required given the retrospective nature of the study.

The primary objective of our study was to compare CD rates in women undergoing IOL at each week of gestation with expectant management to a later gestational age. We divided women into categories based on their gestational age in weeks at delivery (37 0/7-37 6/7, 38 0/7-38 6/6, 39 0/7-39 6/7, and ≥40 weeks). Timing of IOL was determined by the managing physician; there were only 19/863 women (2.2%) delivered >41 0/7 weeks’ gestation so they were combined with the ≥40 weeks group. We excluded cases from the analysis if they had a scheduled CD, ≥1 previous CDs, a noncephalic presentation, or a major fetal anomaly. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were first compared across gestational ages. Next, the impact of IOL was assessed by comparing women who underwent IOL at a specific gestational age with those who were expectantly managed, and this included women who delivered at subsequent gestational age after spontaneous or induced labor.

Because the presence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy may influence the outcomes of IOL we excluded women in the IOL group at each gestational age, but included them in the expectant management group. For example, at 37 weeks, we compared the 64 women who underwent an IOL without a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy to the 712 women who delivered >37 weeks (following IOL or spontaneous labor).

Maternal demographics and clinical characteristics were extracted from medical charts. Overweight and obesity was reported as an index of weight for height (body mass index [BMI]) defined using the World Health Organization guidelines. Birthweight was classified as large (>90th percentile) or small (<10th percentile) for gestational age status based on US national birthweight data. Labor was defined as “none” if the patient had a CD, “spontaneous” if the patient presented with contractions, and “induced” if women were asymptomatic at presentation and required interventions to initiate labor. Mode of delivery was either vaginal or cesarean, and the indication for CD was coded by 1 member of the study team and independently verified by a second member of the study team (C.M.S. and M.N.F.). Cervical dilation, station, and effacement were recorded for each patient at the last outpatient exam >35 weeks’ gestation but prior to the time of either IOL or admission for spontaneous labor. We calculated the simplified Bishop score from the cervical exam at the last outpatient exam (mean 37.5 ± 2.5 weeks of gestation), and we defined a favorable cervix as a simplified Bishop score ≥5 because of comparable sensitivity and specificity for risk of CD when compared to the original Bishop score of ≥8. We also examined several secondary outcomes. The composite neonatal morbidity consisted of hypoglycemia (defined as a capillary glucose value <35 mg/dL within the first 24 hours of life), hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, and respiratory distress syndrome. We also assessed the frequency of neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Statistical analyses were completed using a software package (Stata 13, Special Edition; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were analyzed with the χ 2 or Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed with analysis of variance. Study outcomes by gestational age week were calculated. Univariate logistic regression analyses were undertaken to examine factors related to CD and neonatal morbidity, and variables with P values <.10 on univariate analysis were considered candidates for the multivariable model. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was then undertaken to adjust for potential confounders including nulliparity, prepregnancy BMI, simplified Bishop score, and maternal age for delivery outcomes associated with IOL. Because parity may have a significant impact on the outcomes associated with IOL, we also conducted subgroup analyses for both nulliparous and multiparous women. We controlled for both maternal prepregnancy BMI, and glycemic control (mean fasting and mean postprandial glucose) for neonatal outcomes, and we chose not to include birthweight in the model because it is causally linked to the specified neonatal outcomes. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of women with singleton gestations and GDM who were delivered at Magee-Womens Hospital (University of Pittsburgh, PA) from January 2009 through October 2012. Briefly, the cohort included 1374 women who were diagnosed with GDM if they had either a 50-g, 1-hour glucose challenge test >200 mg/dL, or if they had ≥2 abnormal values on a 100-g, 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test as defined by the criteria of Carpenter and Coustan. For each subject, we included only the first pregnancy during the study period. Women with a prelabor indication for cesarean were excluded from this analysis. To examine the relationship among gestational age, IOL, and the rate of CD in women with GDM, this analysis focused on the 863 women (62.8% of the overall cohort) with either IOL or spontaneous labor ≥37 0/7 weeks ( Figure 1 ). Women included in the study received prenatal care in the maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics clinics at our hospital. Regulatory approval was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was not required given the retrospective nature of the study.

The primary objective of our study was to compare CD rates in women undergoing IOL at each week of gestation with expectant management to a later gestational age. We divided women into categories based on their gestational age in weeks at delivery (37 0/7-37 6/7, 38 0/7-38 6/6, 39 0/7-39 6/7, and ≥40 weeks). Timing of IOL was determined by the managing physician; there were only 19/863 women (2.2%) delivered >41 0/7 weeks’ gestation so they were combined with the ≥40 weeks group. We excluded cases from the analysis if they had a scheduled CD, ≥1 previous CDs, a noncephalic presentation, or a major fetal anomaly. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were first compared across gestational ages. Next, the impact of IOL was assessed by comparing women who underwent IOL at a specific gestational age with those who were expectantly managed, and this included women who delivered at subsequent gestational age after spontaneous or induced labor.

Because the presence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy may influence the outcomes of IOL we excluded women in the IOL group at each gestational age, but included them in the expectant management group. For example, at 37 weeks, we compared the 64 women who underwent an IOL without a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy to the 712 women who delivered >37 weeks (following IOL or spontaneous labor).

Maternal demographics and clinical characteristics were extracted from medical charts. Overweight and obesity was reported as an index of weight for height (body mass index [BMI]) defined using the World Health Organization guidelines. Birthweight was classified as large (>90th percentile) or small (<10th percentile) for gestational age status based on US national birthweight data. Labor was defined as “none” if the patient had a CD, “spontaneous” if the patient presented with contractions, and “induced” if women were asymptomatic at presentation and required interventions to initiate labor. Mode of delivery was either vaginal or cesarean, and the indication for CD was coded by 1 member of the study team and independently verified by a second member of the study team (C.M.S. and M.N.F.). Cervical dilation, station, and effacement were recorded for each patient at the last outpatient exam >35 weeks’ gestation but prior to the time of either IOL or admission for spontaneous labor. We calculated the simplified Bishop score from the cervical exam at the last outpatient exam (mean 37.5 ± 2.5 weeks of gestation), and we defined a favorable cervix as a simplified Bishop score ≥5 because of comparable sensitivity and specificity for risk of CD when compared to the original Bishop score of ≥8. We also examined several secondary outcomes. The composite neonatal morbidity consisted of hypoglycemia (defined as a capillary glucose value <35 mg/dL within the first 24 hours of life), hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, and respiratory distress syndrome. We also assessed the frequency of neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Statistical analyses were completed using a software package (Stata 13, Special Edition; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were analyzed with the χ 2 or Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed with analysis of variance. Study outcomes by gestational age week were calculated. Univariate logistic regression analyses were undertaken to examine factors related to CD and neonatal morbidity, and variables with P values <.10 on univariate analysis were considered candidates for the multivariable model. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was then undertaken to adjust for potential confounders including nulliparity, prepregnancy BMI, simplified Bishop score, and maternal age for delivery outcomes associated with IOL. Because parity may have a significant impact on the outcomes associated with IOL, we also conducted subgroup analyses for both nulliparous and multiparous women. We controlled for both maternal prepregnancy BMI, and glycemic control (mean fasting and mean postprandial glucose) for neonatal outcomes, and we chose not to include birthweight in the model because it is causally linked to the specified neonatal outcomes. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Of the 863 women included in this analysis, 169 (19.6%) had a CD while 694 (80.4%) had a vaginal delivery. There were significant differences in maternal characteristics by gestational age at delivery. Women delivered at earlier gestational ages were more likely to be black and had higher prepregnancy BMI ( Table 1 ). Women delivered at earlier gestational ages had higher values on the 50-g glucose challenge test as well as higher fasting, 1-hour and 2-hour values on the 100-g oral glucose tolerance test ( Table 1 ). Similarly, mean fasting and postprandial home glucose values were higher in women delivered at earlier gestational ages, suggesting that concern for suboptimal maternal glycemic control may have influenced physician behavior when planning for timing of delivery ( Table 1 ). Spontaneous labor was more common in women who delivered <39 weeks, and IOL was more common >39 weeks. We also found that the proportion of women with a favorable simplified Bishop score was stable across gestation.

| 37 wk, n = 151 | 38 wk, n = 184 | 39 wk, n = 399 | ≥40 wk, n = 129 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 31.1 (±5.6) | 31.0 (±5.2) | 30.5 (±5.4) | 30.2 (±5.6) | .41 |

| Primigravida | 99 (51.0) | 90 (48.9) | 233 (58.4) | 106 (81.5) | <.001 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 107 (70.9) | 135 (73.4) | 312 (79.2) | 89 (68.5) | .005 |

| Black | 32 (21.2) | 29 (15.8) | 42 (10.5) | 17 (13.1) | |

| Other | 12 (8.0) | 20 (10.9) | 45 (11.3) | 24 (18.5) | |

| Smoking | 18 (11.9) | 22 (12.0) | 33 (8.3) | 11 (8.5) | .38 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 30.8 (±7.2) | 30.3 (±8.2) | 29.3 (±7.9) | 27.0 (±6.8) | <.001 |

| GCT result, mg/dL | 176.4 (±33.7) | 169.2 (±29.0) | 167.3 (±26.4) | 160.2 (±20.3) | <.001 |

| GTT result, mg/dL | |||||

| Fasting | 95.7 (±16.3) | 91.3 (±13.1) | 90.0 (±14.6) | 87.2 (±10.8) | <.001 |

| 1 h | 197.2 (±24.6) | 196.4 (±23.2) | 194.4 (±26.8) | 190.0 (±22.6) | .10 |

| 2 h | 179.4 (±29.8) | 174.1 (±24.1) | 177.0 (±28.8) | 174.6 (±20.1) | .30 |

| 3 h | 129.7 (±33.5) | 119.2 (±36.5) | 127.8 (±35.4) | 129.1 (±33.5) | .03 |

| Mean fasting glucose, mg/dL | 91.7 (±13.1) | 88.6 (±9.7) | 87.3 (±8.7) | 84.8 (±7.6) | <.001 |

| Mean postprandial glucose, mg/dL | 127.2 (±15.8) | 122.5 (±12.8) | 122.0 (±11.4) | 116.7 (±11.4) | <.001 |

| Labor type | |||||

| Spontaneous | 63 (41.7) | 96 (52.2) | 109 (27.3) | 43 (33.3) | <.001 |

| Induced | 88 (58.3) | 88 (47.8) | 290 (72.7) | 86 (66.7) | |

| Simplified Bishop score ≥5, n = 765 | 25 (19.1) | 34 (23.0) | 72 (19.7) | 18 (15.0) | .44 |

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | 31 (20.5) | 42 (22.8) | 45 (11.3) | 6 (4.6) | |

| Labor | 7 (11.1) | 9 (9.4) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (4.7) | <.001 |

| Induced | 24 (27.3) | 33 (27.5) | 42 (14.5) | 4 (4.7) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree