Thrombocytopenia

INTRODUCTION

Thrombocytopenia in neonates is defined as a platelet count of less than 150 × 109/L. The prevalence of thrombocytopenia in healthy term infants is 1%–2%, whereas up to 35% of neonates admitted to intensive care units may have low platelet counts.1 There are developmental differences in megakaryopoiesis between neonates and older children. Neonatal megakaryocytes are less capable of upregulating platelet production or mounting as high a level of thrombopoietin (Tpo) when compared to adults with the same degree of thrombocytopenia.2 These developmental differences account for the vulnerability of sick neonates to thrombocytopenia.

The major causes of neonatal thrombocytopenia are increased platelet consumption or decreased platelet production. However, both mechanisms can contribute to thrombocytopenia in any given patient, particularly in sick or premature neonates.

DIAGNOSIS/INDICATION

Clinical Findings: History and Physical

A detailed medical history and physical examination will guide the diagnostic approach to thrombocytopenia. Medical history and complications during pregnancy are important because many maternal factors can cause neonatal thrombocytopenia. Maternal drugs and antibodies that cross the placenta can affect an infant’s platelet count. Complications during pregnancy that result in chronic fetal hypoxia or intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) are frequent causes of early-onset neonatal thrombocytopenia.3 Causes of chronic fetal hypoxia and IUGR include pregnancy-induced hypertension or diabetes, placental insufficiency, and placental infarction or malformation. Perinatal asphyxia is another common cause of early-onset thrombocytopenia. Family history of chronic thrombocytopenia suggests a hereditary thrombocytopenia or a genetic syndrome associated with low platelet counts; a family history of previous neonatal thrombocytopenia suggests maternal immune-mediated thrombocytopenia.

Physical findings of thrombocytopenia vary with the platelet count and the primary cause of thrombocytopenia. Many neonates are asymptomatic. However, in those who have bleeding manifestations, bruising and petechiae are the most common presenting symptoms, often noted on the face and head secondary to birth trauma. Thrombocytopenia commonly is associated with mucocutaneous bleeding. Bleeding also can occur with trauma following phlebotomy, after intramuscular injections (prophylactic vitamin K or hepatitis vaccine), umbilical stump bleeding, or associated with circumcision. Intra-abdominal bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) generally occur only in severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50 × 109/L). A bulging fontanel, seizures, or other neurologic signs in a thrombocytopenic neonate warrant urgent radiographic evaluation for an intracranial bleed. Sick infants in the intensive care unit also may have bleeding from intravenous sites, surgical sites, or endotracheal tubes.

Confirmatory/Baseline Tests

When a low platelet count is suspected, a complete blood cell count (CBC) with a review of the peripheral blood smear should be done. The diagnostic approach to multilineage cytopenias is different from that for isolated thrombocytopenia. The morphology of platelets as well as red and white blood cells (WBCs) may provide clues to diagnosis. For example, the presence of WBC inclusions and large platelets suggests a hereditary macrothrombocytopenia, and the presence of microangiopathic red blood cell changes will lead to further investigation for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or other microangiopathic hemolytic processes. Thrombocytopenia is often an incidental finding when a CBC is obtained for assessing other hematologic parameters. In these cases, the primary reason for a CBC may explain the thrombocytopenia (eg, an elevated WBC count in an infant born to mother who has a fever most likely has thrombocytopenia secondary to sepsis). If the clinical picture is not consistent with the degree of thrombocytopenia, the platelet count should be repeated. Spurious thrombocytopenia can be seen with platelet agglutination or platelet satellitism.4 Both are often associated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), the anticoagulant in sample collection tubes. If spurious thrombocytopenia is suspected, review of the peripheral blood smear should provide the accurate count.

Differential Diagnosis/Diagnostic Algorithm

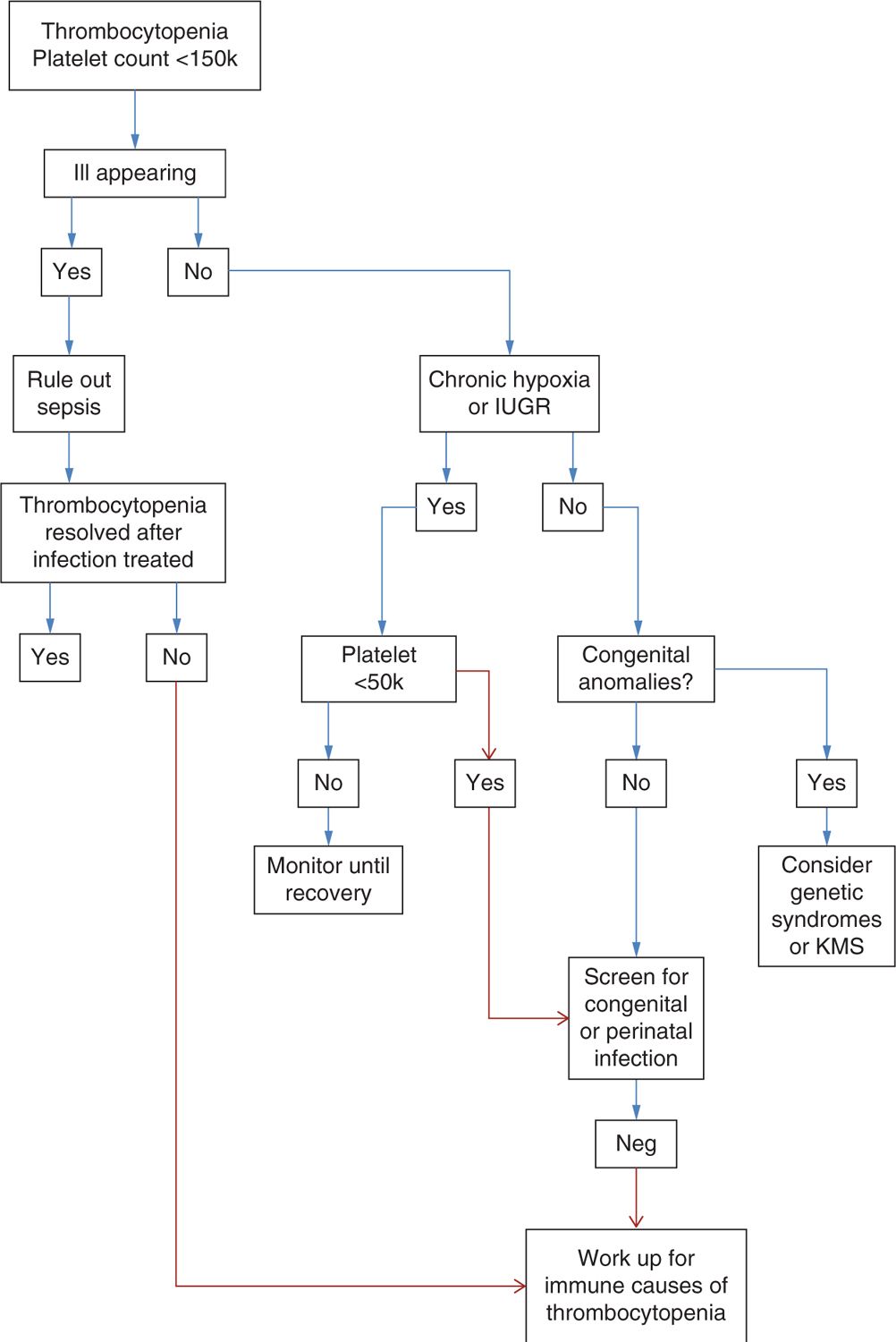

The differential diagnosis for neonatal thrombocytopenia is broad (see Figure 92-1 for a diagnostic algorithm). A most useful approach in sorting out the cause is based on the neonate’s clinical status. Thrombocytopenic neonates roughly fall into three different groups based on their clinical features (Table 92-1).

FIGURE 92-1 Diagnostic algorithm. IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; KMS, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome.

Table 92-1 Differential Diagnosis of the Thrombocytopenic Newborn

Differential diagnosis of neonates with thrombocytopenia who are ill appearing, born prematurely, born to a mother with pregnancy complications and with other signs of medical illness considers the following:

Pregnancy complications:

Chronic hypoxia from placental insufficiency

Intrauterine growth retardation

Preeclampsia

Labor and delivery complications:

Hypoxia or acidosis after birth trauma

Infections:

Bacterial infections (sepsis)

Congenital viral infections (cytomegalovirus, rubella)

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

Neonatal complications:

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

Thrombosis (DIC, indwelling vascular catheters, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO])

Exchange transfusions

Neonatal diseases:

Bone marrow disorders (leukemia, neuroblastoma or other solid tumors, storage diseases)

Neonates with thrombocytopenia and physical abnormalities or dysmorphic features:

Thrombocytopenia with absent radius (TAR) syndrome

Amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and radioulnar synostosis (ATRUS)

Jacobsen syndrome

Chromosomal disorders caused by trisomy 13, 18, or 21 and Turner syndrome

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome

Neonates with thrombocytopenia but who are otherwise healthy appearing with no physical abnormalities or other medical conditions:

Occult infection

Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia:

Secondary to maternal autoimmune thrombocytopenia (ITP)

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT)

Amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia

Hereditary macrothrombocytopenias

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS)

Bernard-Soulier syndrome

ILL-APPEARING PREMATURE INFANTS BORN TO MOTHERS WITH SIGNS OF MEDICAL ILLNESS

Within the group of premature neonates with thrombocytopenia who are ill appearing and born to mothers with pregnancy complications or with other signs of medical illness, the time of onset of thrombocytopenia is useful to further guide the inquiry.

Mild-to-moderate thrombocytopenia (50,000–100,000) developing within the first 72 hours is most likely secondary to maternal/pregnancy-related factors.3,5 Fetuses exposed to chronic intrauterine hypoxia from a variety of complications as well as fetuses with IUGR are often thrombocytopenic at birth. The pathophysiology for the low platelet count is thought to be related to decreased platelet production, a consequence of reduced megakaryocyte progenitors and inadequate upregulation of Tpo.2 Often, these neonates also will have neutropenia, nucleated red blood cells (nRBCs), and sometimes polycythemia. These hematologic abnormalities generally are not severe and resolve within the first 2 weeks of life. This group of patients can safely be monitored without additional workup until thrombocytopenia has resolved. However, if thrombocytopenia persists beyond 10 days or becomes severe (less than 50,000), further workup is warranted.

Infections, a frequent cause of thrombocytopenia in both term and preterm infants, should be ruled out in any ill-appearing newborn with low platelet count. Congenital, perinatal, or acquired postnatal infections all are associated with thrombocytopenia.

Bacterial sepsis is the most common cause of late onset of thrombocytopenia, occurring at greater than 72 hours of life.1,3 Thrombocytopenia secondary to bacterial infection usually develops rapidly and is often severe, particularly in preterm infants. Gram-negative sepsis leads to a most severe thrombocytopenia. DIC frequently complicates neonatal sepsis and is a major mechanism for the low platelet count observed in infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree