The Vermiform Appendix in Relation to Gynecology

Amanda C. Yunker

DEFINITIONS

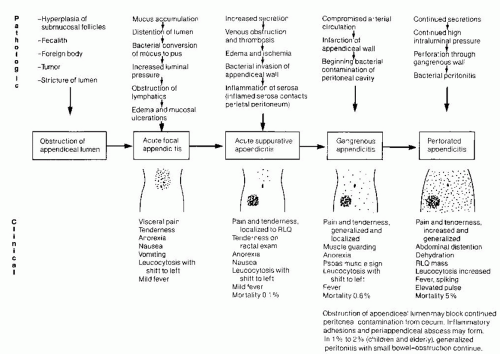

Appendicitis—Inflammation of the appendix, usually caused by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen, with subsequent distention of the appendix with secretions, venous congestion, bacterial proliferation, ischemia, and necrosis.

McBurney point—A point on the anterior abdominal wall, located 1/3 the distance between the right anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus.

Obturator sign—Increased pain in the abdomen, specifically the right lower quadrant, with passive internal rotation and flexion of the right lower extremity at the hip joint.

Psoas sign—Increased pain in the abdomen as the right lower extremity is moved into extension, with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, and asking the patient to actively flex the leg at the hip joint against resistance.

Rovsing sign—Pain reported by the patient in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen while applying pressure to the left lower quadrant.

Fecalith—An intestinal stone formed around a central core of fecal matter.

The vermiform appendix, named for its wormlike appearance, is part of the gastrointestinal tract and usually falls in the purview of general surgeons. However, there are several gynecologic and obstetric associations with the appendix, some of which could be fatal, requiring the obstetrician-gynecologist to be mindful of this organ, its potential diseases, and its effects on other gynecologic structures.

The appendix is most commonly evaluated for acute abdominal pain, which could be the result of acute appendicitis. This occurs in 7% of the population over a lifetime, resulting in the most commonly performed emergent surgical procedure: appendectomy. It is estimated that approximately 300,000 emergent appendectomies are performed annually in the United States. The majority of cases occur in young patients, usually under age 20. However, appendicitis can occur even in elderly patients, and these patients have much higher morbidity and mortality rates associated with appendicitis and appendectomy, compared with their younger counterparts.

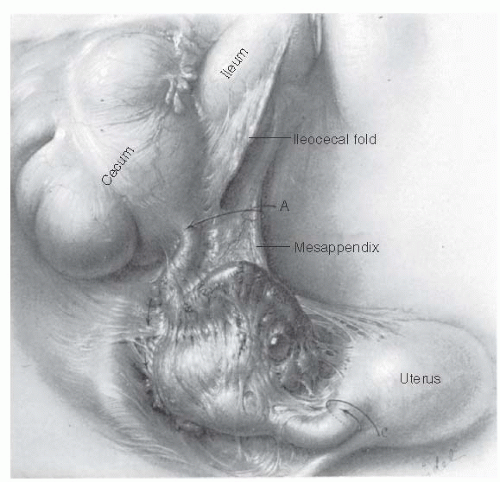

As an obstetrician-gynecologist, the appendix is of interest for many reasons. First, women presenting with acute-onset abdominal pain will likely be referred to a gynecologist for evaluation. Appendicitis should be included in the differential, along with pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cyst, ovarian torsion, and urinary tract infection. Second, acute appendicitis, especially if the appendix is ruptured, can have a negative impact on fertility given the anatomic proximity of the appendix to the fallopian tubes (Fig. 46.1). Third, though infrequent, appendicitis can occur during pregnancy and is associated with a higher morbidity in pregnant females

compared to nonpregnant females. Pregnancy can complicate the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain simply because the pregnancy itself adds multiple etiologies for abdominal pain, and the anatomic location of the appendix can shift cephalad due to the gravid uterus. This can delay diagnosis. Finally, several gynecologic conditions—endometriosis, mucinous tumors, and ectopic pregnancy—can involve the appendix, thus compelling the obstetrician-gynecologist to include the appendix in the evaluation for chronic and acute gynecologic conditions.

compared to nonpregnant females. Pregnancy can complicate the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain simply because the pregnancy itself adds multiple etiologies for abdominal pain, and the anatomic location of the appendix can shift cephalad due to the gravid uterus. This can delay diagnosis. Finally, several gynecologic conditions—endometriosis, mucinous tumors, and ectopic pregnancy—can involve the appendix, thus compelling the obstetrician-gynecologist to include the appendix in the evaluation for chronic and acute gynecologic conditions.

ANATOMY AND FUNCTION OF THE APPENDIX

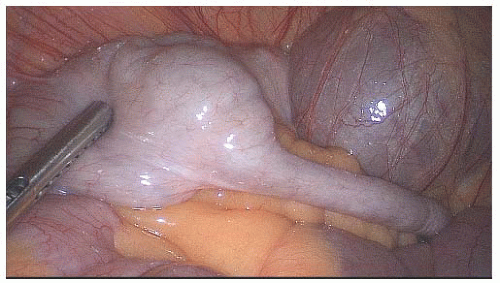

The appendix begins in infancy as a cone-shaped diverticulum at the base of the cecum. As the cecum grows in length and repeatedly distends with bowel function, the appendix eventually elongates and emerges 2 to 3 cm below the ileocecal valve. At full maturation, it is approximately 10 cm in length and 3 to 5 mm in width. The teniae coli travel along the cecum and then converge at the appendix, creating the outer longitudinal muscle of the appendix. This is helpful, in that the teniae may be followed to locate an appendix that may be hidden from view. One instance in which that occurs is a retrocecal appendix, which is found in 16% of adults. In the rest, the appendix is freely mobile and usually easily seen upon mobilization of the cecum (Fig. 46.2). The location of the appendix thus can vary and may influence the location of perceived pain during acute appendicitis.

Early in life, the appendix is composed of large collections of lymphoid follicles that then atrophy and decrease over time. This occurs with simultaneous fibrosis of the wall of the appendix and possible obliteration of the lumen. The lumen itself is lined with colonic mucosa, and the wall of the appendix is composed of smooth muscle, similar to the large and small bowel.

The appendix is supplied by two arterial branches. The main artery for the appendix is the appendicular artery, a branch of the ileocolic artery. It runs parallel to the appendix, in the mesoappendix. The base of the appendix is also supplied by a branch of the posterior cecal artery.

Thought to be primarily a vestigial organ, current general consensus is the appendix serves no function in humans. Due to the large presence of lymphoid tissue in childhood, the hypothesis exists that the appendix once played a role in immune protection of the intestinal tract. Additionally, the appendix does secrete immunoglobulin A, a mucosal surface antibody, thus bolstering the idea that it serves some immune function. However, the amount of secretion is minimal, and the majority is not likely to breach the lumen into the cecum. Thus, removal of the appendix results in no obvious negative physiologic consequence.

ACUTE APPENDICITIS

Pathology arises within the appendix usually as a result of lumen obstruction. The most common cause of obstruction is fecaliths (50%), but other possibilities include lymphoid hyperplasia, malignancy, parasitic infections, endometriosis, and ingested foreign bodies (such as gum, teeth, nails, fruit pits, etc.). Once the lumen is blocked, the appendiceal secretions have no exit, resulting in venous congestion, ischemia, and necrosis. The bacteria, which are already present within the appendix lumen, become trapped and replicate, resulting in local tissue inflammation and pus formation. If untreated, rupture and abscess formation can occur. Leakage of the bacteria through the perforation and into the abdominal cavity leads to peritonitis (Fig. 46.3).

The lifetime risk for developing appendicitis is around 7%, with the majority of patients presenting in the second and third decade of life. The risk of mortality is this group is low, less than 1%, due to appropriate detection and early treatment. However, in individuals over age 50, although the incidence of appendicitis is extremely low, the risk of mortality from acute appendicitis is higher—5% to 15%. This group is also at risk for increased morbidity (50% to 60%) from the disease, such as longer hospitalization, wound infection, higher rates of perforation, sepsis, and other organ failure.

The diagnosis of appendicitis is usually delayed in the elderly, thus resulting in a far-advanced disease process when treatment is eventually started. This delay is likely a result of many factors: The elderly tend to delay seeking care, their symptoms are less specific than are those of their younger counterparts, and they have decreased febrile response and less prominent leukocytosis.

Clinical Presentation

The most common presenting symptom of acute appendicitis is abdominal pain, which is present in more than 95% of patients with appendicitis. The pain usually begins as diffuse and mild and is located in the periumbilical region. Once the disease process has progressed, the pain typically moves to the right lower quadrant, specifically to an area called McBurney point. The pain can be associated with fever, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Many times, there will be aggravation of the pain with movement. This has led to the development of many named physical exam tests, which are aimed at eliciting peritoneal stretch and irritation. These tests will be discussed below.

It should be stressed that the typical physical symptoms— pain, fever, nausea, and anorexia—are only present in 50% of patients, leaving an atypical presentation in the remaining 50%. The location of abdominal pain is variable, depending on the location of the appendix and the stage of the disease process. Although the location of the cecum is fairly constant, the appendiceal tip can be in the right upper quadrant (retrocecal), cul-de-sac, or anywhere between these two locations. As mentioned above, age also can affect the severity of pain felt by the patient. Elderly patients tend to report less severe and more diffuse abdominal pain. In a similar manner, abdominal pain is difficult to diagnose in children and infants because of the lack of ability to effectively communicate their symptoms. The incidence of appendiceal perforation is higher in these two groups for these reasons; thus, the vigilant practitioner must rely on other signs and symptoms and have a higher degree of suspicion when evaluating these patient populations. The presence of associated signs and symptoms is even more variable.

Evaluation

Evaluation for appendicitis begins with the history and physical exam, then usually also includes several laboratory and imaging tests. The physical exam typically focuses on the abdomen and includes several “signs” that indicate peritoneal inflammation. Patients with appendicitis usually have tenderness to direct palpation (especially over McBurney point—located 1/3 the distance from the right anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus), rebound tenderness, and guarding of the abdomen. The Rovsing sign is often present and is described as pain in the right lower quadrant when pressure is applied to the left lower quadrant. Additionally, the patient may be positive for the psoas sign (increased pain in the abdomen as the right lower extremity is moved into extension, with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, and asking the patient to actively flex the leg at the hip joint against resistance) or the obturator sign (increased pain in the abdomen, specifically the right lower quadrant, with passive internal rotation and flexion of the right lower extremity at the hip joint). A complete exam should include rectal and pelvic exams, which, in addition to identifying peritoneal tenderness, also can help rule in the presence of a mass or pelvic abscess.

The most common abnormal laboratory finding in a patient with appendicitis is leukocytosis. The average increase is to 15,000 WBC/mL; however, elevations in WBC are not specific for only appendicitis. Thus, leukocytosis is significant for appendicitis in the setting of the above classical presenting symptoms. Alone, leukocytosis, even with fever, is not a reliable test for appendicitis. Other causes of infection should be ruled out. Other laboratory tests that have been used included C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Because these two tests are nonspecific indicators for inflammation, they also are not helpful as individual tests for appendicitis.

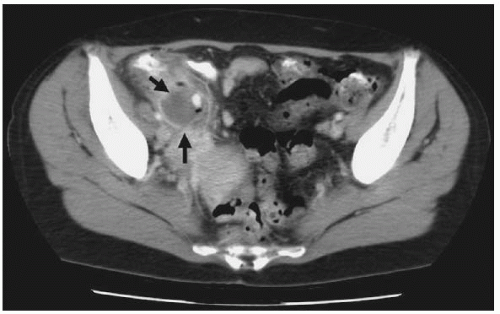

Radiologic evaluation for appendicitis has increased over time and has come to include multiple different modalities. Imaging studies can be helpful in that they can image not only the appendix but also the adjacent abdominal structures, thus ruling in or out other diagnoses that can cause abdominal pain. Currently, computed tomography (CT) is usually the initial imaging technique used in emergency departments across the United States. Its diagnostic ability has been reported to be as high as 87% to 100% sensitivity and 95% to 99% specificity. Findings on CT that indicate acute appendicitis include enlarged appendix (≥6 mm), appendiceal wall thickening, periappendiceal fat stranding, and appendiceal wall enhancement (Fig. 46.4). CT may also diagnose an appendicolith, abscess, or the presence of free air. The Surgical Infection Society and Infectious Disease Society of America recommend helical CT with IV contrast only as the test of choice in patients with suspected appendicitis, if imaging is indicated and necessary. One benefit of preoperative imaging in patients with suspected appendicitis is the reduction in negative appendectomies (those with no pathology).

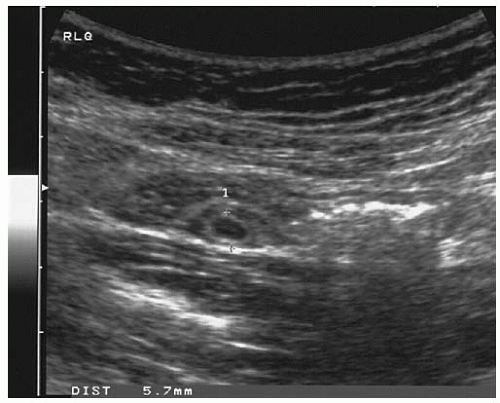

Ultrasound, unlike CT, is operator dependent, and its accuracy for diagnosis of appendicitis varies from institution to institution. However, in a comparison between the two imaging types, both CT and US were highly specific (93% to 95%) in both adults and children, whereas CT was more sensitive.

FIGURE 46.4 Computed tomography of appendiceal abscess. Note complex fluid mass with an enhancing rim in the right lower quadrant (arrows). (Courtesy of Ronald Arildsen, MD, Vanderbilt University.) |

Ultrasound is beneficial in that it does not expose patients to ionizing radiation and thus can be used safely in pregnant patients. Most young women presenting for acute abdominal/pelvic pain, even those who are not pregnant, usually undergo US evaluation of the reproductive organs. Thus, performing US evaluation of the appendix is efficient, convenient, and costeffective. The technique involves directing gradual pressure over the right lower quadrant in an attempt to collapse the overlying bowel and visualize the appendix. A typical “target appearance” identifies the appendix by characteristic changes within its wall (Fig. 46.5). Findings on US that are associated with acute appendicitis include increased appendiceal diameter (≥6 to 7 mm), loculated pericecal fluid, luminal distention, lack of compressibility, prominent pericecal fat, and loss of the submucosal layer.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently being investigated as a potential diagnostic tool for acute appendicitis. Its disadvantages include its much higher cost, when compared to CT or US, and its decreased availability to smaller/more rural institutions. However, there may be some advantages in special patient populations, such as pregnancy, which is discussed later.

Laparoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic for acute appendicitis. If clinical suspicion is high enough, then surgical evaluation is justified. However, appendectomy for a nonpathologic appendix is not without risk. The goal of the presurgical evaluation—history, physical exam, and laboratory and imaging tests—is to determine who will most benefit from surgery and to decrease the negative appendectomy rate, which still hovers between 10% and 20%. Close inpatient observation may be indicated when there is an atypical presentation to allow progression of the clinical picture and completion of the diagnostic workup. If the gynecologist is the admitting attending physician, the consultation of the general surgery service should occur during this time interval.

Patients with persistently confusing findings may benefit from laparoscopy. In almost all circumstances, a laparoscopy with negative findings is preferable to delaying while an appendix ruptures or pelvic inflammatory disease progresses or an ovarian torsion results in a necrotic ovary. An unnecessary delay increases the likelihood of perforation, peritonitis, abscess formation, and sepsis. In a young woman, this also increases her risk of future adhesions, pelvic pain, and infertility. When surgery is performed within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, less than 20% of infected appendices are perforated, compared with 70% when appendectomy occurs greater than 48 hours after symptom onset.

Treatment

As a rule, the best treatment of appendicitis is appendectomy. However, there are circumstances in which appendectomy can be or should be delayed. In those instances, other options include antibiotic therapy and interventional radiologic drainage of abdominal abscess.

Antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly and include broad-spectrum coverage. A common combination of antibiotic treatment is cefazolin and metronidazole. Patients should remain nil per os during antibiotic treatment, in the event that the clinical picture worsens and immediate surgery is required. Antibiotics given prior to surgery have been shown to reduce the incidence of postoperative wound infections. The duration of antibiotic treatment after appendectomy varies. If the appendix was not ruptured at the time of surgery, then antibiotics can be discontinued immediately after. If perforation occurred, most surgeons advocate continued use of wide-spectrum antibiotics for several days after appendectomy, until the patient shows significant clinical improvement and resolution of the infection.

Several studies have been reported over the last few years comparing nonoperative versus operative management of

acute, uncomplicated appendicitis. In many of these studies, patients were offered antibiotics as their sole therapy if they desired and their surgeons agreed. If their symptoms improved on intravenous antibiotics, they were discharged on oral antibiotics with close follow-up. Failure of antibiotic therapy, either by physical exam or laboratory, resulted in immediate appendectomy. The majority of patients who were treated with antibiotics alone was adequately treated and did not require subsequent surgery. While overall the data look somewhat promising, there is still great hesitancy to adopt this antibioticonly strategy as the primary treatment for appendicitis.

acute, uncomplicated appendicitis. In many of these studies, patients were offered antibiotics as their sole therapy if they desired and their surgeons agreed. If their symptoms improved on intravenous antibiotics, they were discharged on oral antibiotics with close follow-up. Failure of antibiotic therapy, either by physical exam or laboratory, resulted in immediate appendectomy. The majority of patients who were treated with antibiotics alone was adequately treated and did not require subsequent surgery. While overall the data look somewhat promising, there is still great hesitancy to adopt this antibioticonly strategy as the primary treatment for appendicitis.

Another nonsurgical option for treatment of acute appendicitis is catheter drainage of periappendiceal abscess under CT or US guidance. This treatment option may be helpful in controlling the spread of infection prior to appendectomy. Limitations of percutaneous drainage include the inability to drain multiloculated abscesses, inaccessible location, and the possible need for anesthesia. If possible, once the abscess is drained and antibiotics have allowed the infectious process to “cool,” an interval appendectomy can be performed. Most surgeons wait 6 to 12 weeks after nonoperative therapy to perform an interval appendectomy.

Open Appendectomy

|