Podocin deficiency or podocin-induced focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) accounts for 10% to 30% of cases of pediatric steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. The age of onset ranges from younger than 1 year of age to adult, depending on the type of NPHS2 mutation, which can be familial or sporadic. The histologic appearance ranges from minimal change disease to FSGS with diffuse podocyte foot process effacement seen by EM.

Diffuse mesangial sclerosis (DMS) is the second most common glomerular pathology found in neonates with congenital nephrotic syndrome and also can present as late as 4 years of age. DMS can be idiopathic or caused by a variety of genetic mutations, including WT1 (Wilms tumor-1, a transcription factor involved in gonad and podocyte differentiation), LAMB2 (laminin β2, associated with Pierson syndrome), and PLCE1 (phospholipase C enzyme). WT1 mutations along with the glomerular finding of DMS can be present in Denys-Drash syndrome, which is characterized by male pseudohermaphroditism and increased risk of Wilms tumor. Therefore, the finding of DMS should prompt investigation for associated genetic mutations and clinical/radiologic exclusion of a renal mass (or Wilms tumor).

In early stages of DMS, histology reveals normal glomeruli with prominent podocytes, which is normal for infants and toddlers. The finding of DMS is different from the matrix expansion that is characteristic of diabetic nephropathy. If DMS were described with current terminology, many of the affected glomeruli would satisfy the current criteria for collapsing glomerulopathy or the collapsing variant of FSGS. These glomeruli can eventually undergo global solidification. By EM, the GBMs can appear thickened and lamellated, which can be reminiscent of Alport hereditary nephritis. There is also variable podocyte foot process effacement.

MINIMAL CHANGE DISEASE

Minimal change disease (MCD) is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children that usually presents with abrupt onset of nephrotic syndrome, which can be accompanied by microscopic hematuria or renal dysfunction. MCD is characterized by a diffuse podocyte injury, but the pathogenesis of MCD remains poorly understood. Secondary forms of MCD associated with medications or neoplasia are more common in adults. Pediatric nephrotic syndrome is often presumed to be MCD and treated empirically with steroids and generally good response to therapy. Kidney biopsies are performed when a patient is steroid resistant to exclude other diseases.

By histology, the glomeruli are normal with delicate GBMs (Fig. 3.2). Tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis also should be absent, and the presence of any tubulointerstitial scarring should raise a suspicion for FSGS, which may not be present in the biopsy sample. In such cases, additional serial tissue sections should be evaluated by light microscopy to exclude the presence of FSGS. In MCD, no immune complexes are detected by IF or EM. The ultrastructural examination shows extensive effacement of the podocyte foot processes (Fig. 3.3), and the absence of a diffuse podocyte injury is incompatible with a diagnosis of MCD.

FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS

FSGS is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults but accounts for 10% to 20% of the nephrotic syndrome in children. FSGS may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to genetic mutations, viral infections, drugs, or structural–functional adaptations. The clinical presentation of FSGS is similar to MCD with abrupt onset of the nephrotic syndrome, which may be associated with renal insufficiency, hypertension, and/or microscopic hematuria. FSGS is often less responsive to corticosteroid therapy than MCD, and approximately 40% to 60% of patients develop ESRD within 10 to 20 years of disease onset. There is also a high rate of recurrence following transplantation, developing in 30% of allografts.

FSGS is characterized by an increase in matrix, hyaline, or inflammatory cells that obliterate the glomerular capillary lumens, which may have either segmental or global involvement. These lesions are characterized by solidification of the glomerular capillary tuft with hyaline accumulation, sometimes with adhesion to Bowman capsule. Intracapillary foam cells within glomeruli may be the predominant lesions in the tip or cellular variant and glomerular sclerosis is not required to establish the diagnosis of the tip or cellular variants of FSGS. Therefore, some FSGS variants are neither segmental (collapsing variant) nor sclerotic (cellular or tip variant), and advanced phases of disease are not limited to being focal (involving <50% of the total glomeruli). Adequate sampling is important because as the name suggests, the glomerular lesions can be very focal; FSGS can be diagnosed based on a single glomerulus. By IF microscopy, nonspecific trapping of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and C3 can be observed in the areas of glomerular sclerosis. This focal or irregular staining distribution argues against an immune complex–mediated injury, which typically has diffuse and global glomerular involvement. EM shows variable but often extensive effacement of the podocyte foot processes.

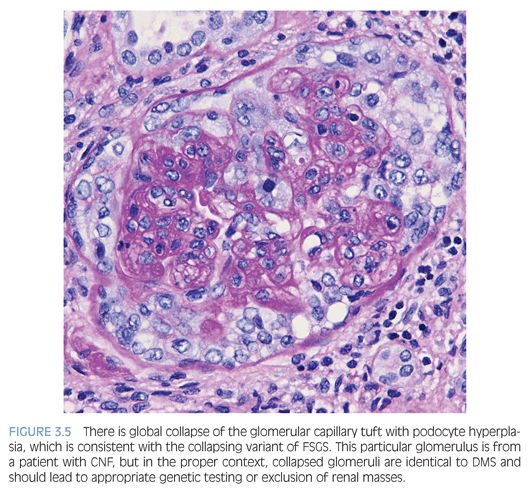

The Columbia FSGS classification2 recognizes the following five variants: 1) tip, 2) perihilar, 3) cellular, 4) collapsing, and 5) not otherwise specified (NOS). The tip variant has the best prognosis because it behaves like MCD and is characterized by a cellular lesion (usually with foamy macrophages) involving less than 50% of the glomerulus or a sclerotic lesion involving less than 25% of the glomerulus adjacent to the urinary pole. These lesions show herniation or confluence of the glomerular capillaries with the epithelial cells at the origin of the proximal tubule (Fig. 3.4). The cellular variant shows endocapillary hypercellularity, which can include foam cells, leukocytes, and occasionally pyknotic or karyorrhectic debris, and has an intermediate prognosis between that of the tip and collapsing variants. The perihilar variant has segmental sclerosis involving the vascular pole and is frequently seen in secondary forms of FSGS. The collapsing variant of FSGS or collapsing glomerulopathy is considered the most aggressive variant with the worst prognosis. This pattern of injury has been variably associated with viral infections, particularly HIV and parvovirus B19; autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus; and drugs/medications, specifically pamidronate. At least one glomerulus must show global or segmental collapse of the capillary tuft with overlying podocyte hyperplasia (Fig. 3.5). As previously mentioned, collapsing FSGS is essentially identical to DMS, and this finding in a young pediatric patient should trigger the appropriate genetic and imaging studies.

IgM nephropathy and C1q nephropathy are two additional entities that may be considered variants within the spectrum of podocyte injury seen in MCD and FSGS. Both are associated with steroid resistance and higher risk of disease progression. Either entity can have normal glomeruli (typical of MCD) or segmental glomerulosclerosis (similar to FSGS). IF microscopy reveals dominant or codominant mesangial staining with an intensity of at least 2+ out of 4+ for IgM or C1q (Fig. 3.6) to diagnose IgM nephropathy or C1q nephropathy, respectively. Ultrastructural evaluation also shows mesangial electron-dense deposits and diffuse effacement of the podocyte foot processes.

MEMBRANOUS NEPHROPATHY

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is an uncommon cause of nephrotic syndrome in children, which contrasts with adults. Primary MN in adults (70% of cases) is associated with autoantibodies targeting the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R), which is expressed on podocytes and proximal tubules.3 However, pediatric MN may involve other antigens because neutral endopeptidase has been identified in a rare form of neonatal MN4 or more recently antibodies to bovine serum albumin, which may be due to an immunologic reaction from ingestion of cow milk.5

By light microscopy, the GBMs range from normal to marked thickening (Fig. 3.7) with subepithelial “spike” formation or a vacuolated appearance when visualized with a Jones methenamine silver stain. There is no significant mesangial or endocapillary hypercellularity in cases of primary MN. There is diffuse granular IF staining of the capillary walls for immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Fig. 3.8) and κ and λ light chains with variable C3 deposition. In primary MN, IgG4 is the dominant subclass present in the immune complexes. The presence of mesangial or extraglomerular immune complexes favors a secondary type of MN, which includes, but is not limited to, infections (e.g., hepatitis B or C virus, syphilis), systemic diseases (lupus, sarcoidosis), and malignancy. The EM findings for MN can be categorized into four stages as described by Ehrenreich and Churg,6 but this has not been shown to be an independent prognostic factor. Ultrastructurally, the deposits have a homogeneous electron-dense appearance with extensive podocyte foot processes effacement (Fig. 3.9), but a microspherular substructure has been described in some cases,7 including the neonatal form of MN involving neutral endopeptidase. The presence of subendothelial or mesangial deposits should raise the suspicion of a secondary form of MN. The subepithelial deposits in postinfectious glomerulonephritis may mimic MN, but the segmental distribution of subepithelial deposits and presence of large subepithelial “humps” can help favor the former diagnosis.

IMMUNOGLOBULIN A NEPHROPATHY/HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common glomerulonephritis (GN) throughout the world and is particularly prevalent in some geographic areas including Southeast Asia. Historically known as Berger disease, IgAN occurs in a wide age range, with a peak incidence between 20 and 30 years of age. The onset of disease is usually insidious with asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria detected on urinalysis, although patients can manifest with nephrotic syndrome and/or acute kidney injury. The pathogenesis of IgAN involves abnormal glycosylation of IgA1 with subsequent mesangial deposition.8 There is variable disease progression with many pediatric patients showing spontaneous remission,9 but there is a substantial risk of progression to ESRD, and IgAN tends to recur in kidney allografts.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a systemic disease that commonly affects pediatric patients, which is also associated with abnormal glycosylation of immunoglobulin A (IgA),10 and the pathologic renal findings are indistinguishable from IgAN. HSP and IgAN are likely related diseases, and infections often precede the onset of either HSP or IgAN. The extrarenal manifestations of HSP are secondary to vasculitis, including purpura, diarrhea, and arthritis. HSP is usually an acute and self-limiting injury, so its prognosis is generally very good in children, depending on the extent of renal involvement.

The histologic features are highly variable in IgAN/HSP. In a minority of cases, the glomeruli are histologically normal. The most common glomerular finding is mesangial expansion with mesangial hypercellularity (defined as >3 mesangial cell nuclei per peripheral mesangial area, in a 3 micron-thick section) (Fig. 3.10). IgAN can manifest itself as a proliferative GN, with varying degrees of endocapillary hypercellularity, and occasional crescent formation. Crescent formation involving more than 50% of the glomeruli is very unusual and should raise suspicion for a superimposed pauci-immune crescentic GN. However, crescent formation is much more common in HSP than IgAN. As these diseases evolve, it is common to encounter segmental and/or global glomerulosclerosis. Interstitial inflammation, if present, is usually mild. In HSP, skin biopsy reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis and IgA deposits are present in a patchy distribution.

The diagnostic IF finding is dominant or codominant IgA glomerular deposition of at least 1+ staining intensity that is predominantly mesangial in distribution with variable capillary wall involvement (Fig. 3.11). This is usually mirrored by less intense staining for IgG, C3, and κ and λ light chains (λ usually staining more intensely than κ). Fibrinogen/fibrin often highlights cross-linked fibrin degradation products that colocalize with the immune complex deposits of IgAN/HSP. C1q staining is unusual and raises the possibility of a lupus or “lupus-like” nephritis.

EM shows many electron-dense deposits in mesangial areas (Fig. 3.12), whereas some subepithelial and/or subendothelial deposits can also be present. The presence of subepithelial “hump”-like deposits should raise suspicion for an IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis, which is discussed in the following section. Podocytes can show variable effacement, which may correlate with the extent of proteinuria.

Several histologic classification systems exist for IgAN and HSP. The most current and widely validated system is the 2009 Oxford IgAN classification,11,12 which factors the presence or absence of mesangial hypercellularity, endocapillary hypercellularity, and segmental glomerulosclerosis, and the extent of tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis. For HSP, the 1977 International Study of Kidney Disease in Children histologic classification is preferred,13 which established categories primarily based on the degree of mesangial proliferation and extent of crescent formation.

POSTINFECTIOUS GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

Postinfectious glomerulonephritis (PIGN) is characterized by an immune complex–mediated glomerular injury following a nonrenal infection. The most well-characterized form of this disease, poststreptococcal GN, presents with abrupt onset of gross hematuria and renal insufficiency between 1 and 4 weeks after an infection by group A Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis or pyoderma.14,15 The identity of the nephritogenic antigen has yet to be determined but is postulated to be cationic with capability to cross the GBM.

The disease is generally self-limited in children, with treatment focused on supportive therapy and antibiotics, and more than 90% of children will regain normal renal function. Poststreptococcal GN continues to be a serious health problem in developing countries, but its incidence is on the decline in industrialized nations.16 Staphylococcal infections are associated with the variant known as IgA-dominant PIGN, which can be mistaken for IgAN.17

The classic appearance of acute PIGN is that of a diffuse and global glomerular injury with abundant circulating neutrophils in the glomerular capillaries (Fig. 3.13) and accentuated lobulation of the glomerular capillary tuft. The GBMs are without duplication, although the subepithelial deposits can rarely be detected on trichrome staining. Cellular crescents, if present, are usually focal. The tubulointerstitium often shows prominent neutrophilic inflammation, which can resemble acute pyelonephritis. Many intratubular red blood cells, or possibly red cell casts, can be seen. In later stages of the disease, with resolution of inflammation, the glomerular alterations are subtle and the diagnosis largely depends on IF and EM findings.

By IF, PIGN typically shows coarse, irregular deposits of IgG (Fig. 3.14) and C3 along the capillary walls in the active stage of the disease, arranged in either a “starry sky” or “garland” pattern, depending on the frequency of the deposits. In the past, the presence of only C3 glomerular staining often raised the consideration of a chronic phase of PIGN. These atypical PIGN cases may overlap with the recently described entity of a C3 glomerulonephritis because many have aberrations in the alternative complement pathway.18,19

In the active phase of PIGN, EM typically reveals scattered large electron-dense deposits (humps) along the subepithelial aspect of the GBM (Fig. 3.15), which do not incite a reaction of basement membrane material (or spike formation). If large humps are not apparent, these cases may be difficult to distinguish from an early stage of MN. In PIGN, mesangial and/or subendothelial deposits are also frequently present.

MEMBRANOPROLIFERATIVE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is an entity that has greatly evolved since its first description, which was initially thought to represent a discrete clinicopathologic entity. However, improved diagnostic tools allowed further refinement as more causes of secondary MPGN, such as hepatitis B or C viral infection, cryoglobulinemia, or paraprotein-related renal diseases, were subsequently identified. Primary MPGN often presents in older children and young adults and is more common in Caucasians. Nephrotic-range proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, and hypocomplementemia are usual features. The disease tends to have a chronic, slowly progressive course. Based on recent identification of abnormalities in the alternative complement pathway, Sethi and Fervenza20 propose to subdivide primary MPGN into either immune complex–mediated or complement-mediated categories as the cases of idiopathic MPGN continue to decrease. These discoveries regarding the importance of the alternative complement pathway initially created the encompassing term of C3 glomerulopathy (discussed in the next section), but the significance is spreading into the realm of primary MPGN as well as some atypical PIGN cases, and it is likely that this will continue to evolve as better understanding and knowledge is gained.

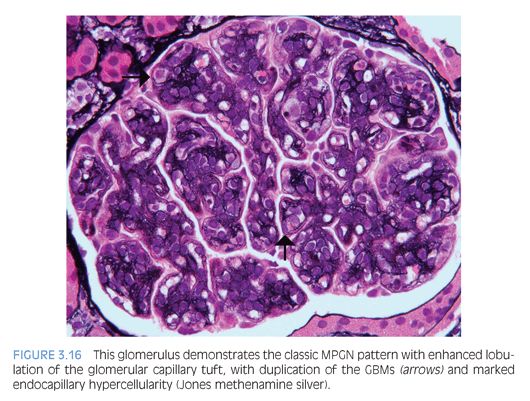

The characteristic histologic findings include accentuation of the lobular architecture of the glomerular tufts with endocapillary hypercellularity and frequent duplication of the GBMs (Fig. 3.16). Inflammatory or mesangial cells may be present or interposed between the duplicated basement membranes. Progressive glomerular injury will eventually lead to interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Both IgG and C3 (Fig. 3.17) IF studies reveal capillary wall and mesangial staining in a coarsely granular pattern. C3 IF alone in the absence of immunoglobulin staining favors a diagnosis of C3 glomerulopathy, which is discussed next. In MPGN, ultrastructural examination reveals many discrete electron-dense deposits throughout the glomerulus, primarily in subendothelial and mesangial locations, as well as duplication of the GBMs with cellular interposition (type I; Fig. 3.18). In MPGN type III, there are also abundant subepithelial to transmembranous deposits.

C3 GLOMERULOPATHY

C3 glomerulopathy is a recently established term that encompasses the entities of dense deposit disease (DDD, formerly MPGN type II) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN). The hallmark of these diseases is C3 glomerular deposition in the virtual absence of immunoglobulin and both are associated with dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway.21,22 These disease entities are uncommon and tend to present in childhood and young adulthood. There is typically some degree of both proteinuria and hematuria at presentation, with variable renal insufficiency. Hypocomplementemia, specifically low C3, is present in a majority of cases of DDD and approximately half of cases of C3GN and should raise suspicion for the presence of C3 nephritic factor (C3NeF), an autoantibody against C3 convertase (C3bBb) that prevents its inactivation. The diagnosis of a C3 glomerulopathy should prompt testing for C3NeF or other described mutations of or antibodies to alternative complement pathway components.

The histologic features of these two diseases widely vary from purely mesangial proliferative changes or variable endocapillary hypercellularity to a membranoproliferative pattern of injury, which typically has a worse clinical course. In DDD, the glomerular and tubular basement membranes can show segmental thickening in areas of complement deposition, with an eosinophilic, refractile, and strongly periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)–positive appearance. Focal crescent formation or an exudative GN can also be seen in either disease.

The IF and EM features of DDD are distinct with segmental ribbonlike staining for C3 along the glomerular and frequently tubular basement membranes, along with granular mesangial staining. In rare cases, this can be accompanied by immunoglobulin or C1q staining. Ultrastructural examination reveals highly osmiophilic dense deposits along the lamina densa of the GBMs, resulting in a very electron-dense appearance, typically in a segmental discontinuous distribution. The deposits lack organized substructure. Similar deposits can be seen in the mesangium, along Bowman capsule, and in the tubular basement membranes. In a subset of cases, subepithelial deposits resembling subepithelial humps have been described, which are less dense than the intramembranous deposits.

The IF and EM features of C3GN are somewhat variable. The disease is defined by bright granular C3 staining, typically in the mesangium and occasionally along the glomerular capillary walls with no significant immunoglobulin or C1q staining. By EM, there are amorphous to discrete electron-dense deposits in the mesangium and scattered subendothelial and/or subepithelial deposits. These deposits are less dense than those of DDD.

LUPUS NEPHRITIS

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a major cause of morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), occurring in 50% to 80% of patients during their disease course. There is a strong predilection for disease involvement in young females. The presentation ranges from asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria to nephrotic syndrome, nephritic syndrome, and varying degrees of renal insufficiency.

LN is categorized into six classes according to the 2003 International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) Classification of Lupus Nephritis.23 In class I (minimal mesangial) LN, the glomeruli are histologically normal, but mesangial immune complex deposition is detectable by IF only or IF and EM. Class II (mesangial proliferative) LN shows varying degrees of mesangial hypercellularity with mesangial immune complexes. Rare subendothelial or subepithelial electron-dense deposits by EM are permissible for class II LN. Class III (focal) or class IV (diffuse) LN are characterized by proliferative (active) and/or sclerosing (chronic) lesions involving less than 50% or 50% or more of the population of glomeruli, respectively. Proliferative or active lesions include prominent subendothelial “wire-loop” deposits, intracapillary deposits (hyaline “thrombi” or pseudothrombi; Fig. 3.19), endocapillary hypercellularity, cellular or fibrocellular crescents, fibrinoid necrosis, GBM rupture, and karyorrhexis. The sclerosing or chronic lesions include segmental or global glomerulosclerosis, fibrous adhesions, and fibrous crescents. For class IV LN, the glomerular injury is further divided into either a segmental (involving <50% of the glomerulus) or global (involving >50% of the glomerulus) designation. Some studies suggest that segmental glomerular injury may be due to a pauci-immune mechanism.24,25 Finally, class III and IV LN are assigned an additional modifier based on whether the lesions are active (A), chronic (C), or mixed (A/C). Class V (membranous) LN is diagnosed when more than 50% of the glomerular capillary loops in greater than 50% of the sampled glomeruli contain subepithelial immune complex deposits as detected by IF and EM. The histologic features are similar to primary MN (discussed earlier) with the additional feature of mesangial hypercellularity and mesangial immune complex deposition. In addition, class V LN can occur concurrently with class III or IV LN. Class VI (advanced sclerosing) LN is diagnosed when more than 90% of the glomeruli are globally sclerosed.