The Febrile Child

Shahinaz E. Soliman

Gregory Plaugher

One of the most common pediatric clinical presentations is that of the febrile child. In an office-based study by Hoekelman et al. (1), 10.5% of 1,068 children, ages 3 to 24 months, had temperatures <100.76°F (38.2°C). Fever comprises approximately 30% of the principal complaints brought to a pediatrician (2). Twenty percent of pediatric emergency room visits (3) and approximately two-thirds of all children in the United States will be evaluated by a health care provider for an acute febrile illness during the first 2 years of life (4). To practitioners and parents alike, it is an alarming and anxiety-provoking issue. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the issues involved in the evaluation and management of the febrile child and the causes of fever in children.

CONTROL OF BODY TEMPERATURE

Body temperature regulation is based on an equilibrium between heat production and heat loss. Heat production depends on the basal metabolic rate, which varies with physical activity, thyroxine levels, and catecholamine levels. On the other hand, heat loss is mediated through evaporation, conduction, and convection. The control of heat production and heat loss is maintained by the thermoregulatory center in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus regulates the normal body temperature by receiving inputs from two main sources: the first source is the peripheral thermoreceptors, and the second source is the temperature of blood perfusing the hypothalamus itself. When the body temperature rises and the hypothalamus receives input from the above two sources it responds by vasodilatation, sweating, and shivering (also a mechanism of pyrogenesis).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF FEVER

Toxins, infectious agents, or antigen-antibody complexes from many different sources, known as exogenous pyrogens, produce fever in humans by initiating the production of a protein, endogenous pyrogen, from phagocytic leukocytes (5). This protein interacts with specialized receptors in the anterior hypothalamus, leading to the production of prostaglandins, monoamines, and probably cyclic adenosine monophosphate (5). Thus, the body’s thermostat is set to a higher level and the patient becomes feverish. The primary pyrogen responsible for fever is interleukin1 (6). This endogenous pyrogen is not stored in the phagocytic leukocytes and takes from one to several hours to be synthesized. When fever takes place, the body responds by vasodilatation, temporarily raising the skin temperature allowing heat loss through the skin to the cooler environment. On the other hand, sweating promotes heat loss via evaporation and at the same time the subject feels warm and seeks a colder atmosphere (7).

THE ROLE OF FEVER

There is an increasingly large body of evidence that seems to support the positive role fever places on the host defenses (8). The fever improves the body’s ability to fight infection by increasing leukocyte mobility, increasing leukocyte bacteriocidal activity, enhancing the interferon effect and T-cell proliferation, and decreasing available trace metals for the pathogenic infection. In animals, the inability to mount a febrile response in the presence of infection is highly associated with increased mortality.

Fever is associated with the release of endogenous pyrogens, leading to the activation of T cells, which presumably enhances the host defenses (9). Elderly or debilitated patients often have little or no fever, and this factor is considered to be a poor diagnostic sign. However, Petersdorf (9) states that there is no reason to believe that fever accelerates phagocytosis, antibody formation, or other defense mechanisms.

FEVER DEFINED

Normal body temperature varies diurnally, with the high temperature occurring in the early evening and low temperature in the early morning. Depending on which authority is consulted (5,8,9), there is a discrepancy as to what is considered normal and abnormal temperature. Normal rectal temperature can range between 96.8°F and 98.6°F (36° and 37°C); however, on rare occasions it may be as low as 95.5°F (35.3°C) or as high as 100.4°F (38°C) (8). For this discussion, in the appropriately clothed child, a rectal temperature more than 100.4°F (38.0°C) will be defined as fever. Oral and axillary temperatures are usually 1°F and 2°F (0.6°C and 1.1°C) lower than rectal, respectively (5). Infrared tympanic membrane thermometry seems to be a reliable method for measuring body temperature, although in children less than 3 months of age the reliability of this method has been questioned. Because even a low-grade fever in this age group can be serious, it is prudent to rely on rectal temperatures in this population of patients (5). Pediatric and emergency medicine residency directors were surveyed and defined fever as >100.4°F (38°C) and 100.58°F (38.1°C), respectively (10).

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

A complex dilemma for any primary health care provider is to determine the mechanism, clinical relevance, and case management of fever in a child. Within the field of medicine there remains a lack of consensus with regard to the treatment of the febrile child (5,8,9).

Infections of the gastrointestinal tracts or the respiratory system account for the majority of fevers in all age groups. Most of these infections are viral in origin (e.g., influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, rotavirus, enterovirus), they are generally self-limiting, and children recover without specific therapy (8,11).

The challenge for the chiropractic clinician is to determine which children have uncomplicated fevers of viral origin versus fever that may be caused by a serious bacterial infection (e.g., meningitis), which requires prompt referral to an emergency room. As an increasing number of parents choose a chiropractor as the primary health care provider for their children, the challenge of managing the patient with fever will increase in complexity. Co-management (MD and DC) of patients, especially when some uncertainty exits with regard to the diagnosis, is in the best interest of all. In this chapter the authors will discuss the different clinical presentations of a febrile child, causes of fever in children, and the possible avenues for case management.

The challenge for the medical physician is to treat children with serious bacterial infections adequately while not overtreating the vast majority of children who have a viral infection (11).

History

Careful attention to the patient’s case history and physical examination will provide the most important clues as to the diagnosis as well as the overall toxicity of the child and thus the urgency of the situation (e.g., will an emergency room referral be required?). The doctor should query the onset and duration of the fever, the degree of temperature (if taken by the parent), any medications given (including antipyretics), associated signs and symptoms or behavioral changes, and the presence of any similar patterns in siblings or playmates (8).

The physician should also inquire about the child’s past medical history such as recurrent febrile illnesses (8), chronic illness, or drug regimens that may compromise the defenses of the host, such as malignancy, sickle cell disease, dysplasia, or immunosuppression (8,11). The Rochester criteria (12) are used to identify those infants who are unlikely to have a serious bacterial infection. In addition to the observation that the infant appears generally well, seven historical criteria are used to identify those infants at low risk:

Born at term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation)

Did not receive prenatal antimicrobial therapy

Was not treated for unexplained hyperbilirubinemia

Had not received and is not receiving antimicrobial agents

Had not been previously hospitalized

Had no chronic or underlying illness

Was not hospitalized longer than mother

The Rochester criteria also includes information derived from the physical and laboratory examinations. Infants at low risk are those that have:

No evidence of skin, soft tissue, bone, joint, or ear infection

Laboratory values:

Peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count 5.0 to 15.0 × 109 cells/L (5,000 to 15,000/mm3)

Absolute band form count ≤1.5 × 109 cells/L (≤15,000/mm3)

Less than or equal to 10 WBCs per high power field (hpf) (×40) on microscopic examination of a spun urine sediment

Less than or equal to 5 WBCs per hpf (×40) on microscopic examination of a stool smear (only for infants with diarrhea)

Topics about which the doctor should query during the history include the following:

Foreign travel

Animal exposure (e.g., leptospirosis)

Drug intake

Vaccination history (see Chapters 15 and 19)

Skin rashes (onset, pattern, distribution)

Any skin changes

Magnitude and pattern of temperature

Any difficulty in breathing

Cough expectoration

Seizures (number, duration)

Level of consciousness

Presence of earache

Any difficulty swallowing

Any bleeding tendency

Any pallor changes

Any loss of weight or failure to thrive

Trauma (e.g., falls, motor vehicle accident, etc.)

Any nasal discharge

Swollen gums

Diarrhea

Constipation

Any abdominal cramps

Red eye(s) or eye swelling

Any blurring of vision

Difficulty in micturition

Any change in color of urine

Cough

Headache

Neck rigidity and/or pain

Food ingestion within the last 48 hours

Abnormal gait/crawling

Any difficulty in movement

Swelling/edema (anywhere on the body, including joints)

Pain (e.g., muscle aches, bone pain, pain of any kind)

Family history (e.g., diabetes insipidus, familial Mediterranean fever)

Chiropractic Management

Once a chiropractor has been presented with a febrile child, he or she must address two main considerations. First, what is the source of the fever? Second, what is the best management approach for the patient?

Clinically, the chiropractic and osteopathic communities have observed the effect of spinal adjustments and their apparent influence on immune system function in a variety of disorders (13,14,15). The chiropractor is now challenged to determine when correcting the vertebral subluxation and its impact on the immune system is sufficient or when a referral to the pediatrician or emergency physician for further evaluation and treatment is necessary. Referral for evaluation and treatment does not exclude the continuation of chiropractic care where indicated. Provided that no contraindications exist (i.e., joint laxity as in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), an adjustment should be administered when signs of subluxation exist regardless of the patient’s concurrent disease state. Chiropractic care falls under the rubric of overall supportive care in the case management of most patients with fever.

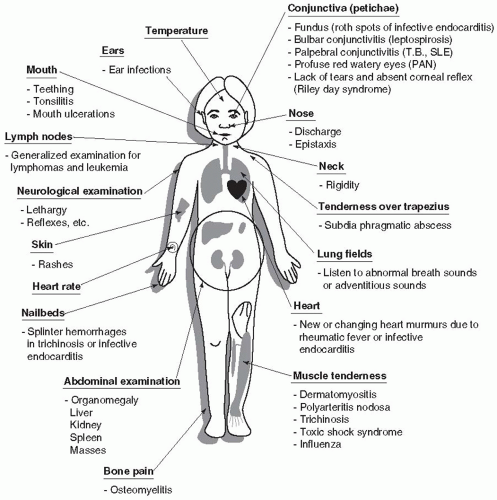

When deciding on the appropriate course of management of the acutely febrile child, the following examination procedure is recommended (16,17). After a complete history (see above discussion), the vital signs of the child should be examined, followed by a thorough physical and spinal examination (see Chapters 5 and 15) (Fig. 17-1).

Vitals

Temperature For the young infant, the rectal temperature is measured. Place the infant in the prone position and, with the infant’s buttocks spread, a welllubricated thermometer is inserted slowly through the anal sphincter to approximately 1 in.

Pulse Determine the pulse by auscultation of the heart. The average heart rate of a newborn ranges from 120 to 140 beats per minute (bpm). Wide fluctuations may occur to as fast as 190 bpm during crying to 90 bpm during sleep.

Respiratory Rate Both the respiratory rate and respiratory effort should be carefully assessed. The respiratory rate varies between 30 and 50 breaths per minute and should be observed for 1 to 2 minutes because of periods of apnea and periodic breathing, especially among pre-term infants. Look for grunting respirations and chest retractions, which are signs of respiratory distress.

Blood Pressure Blood pressure may be difficult to assess in a child, especially for infants younger than 6 months of age. In such cases, the flush method may be used. The arm is elevated while an uninflated cuff is applied. The arm is then “milked” from the fingers to the elbow so that blanching of the skin occurs. The cuff is inflated to just beyond the estimated blood pressure. The arm is then placed by the patient’s side and the cuff pressure is allowed to fall slowly. A sudden flush of skin color occurs at a pressure level slightly lower than the true systolic pressure. With this method, the systolic blood pressure of a 1-day-old child is about 50 mm Hg and, by the second week of life, it is 80 mm Hg. By the end of the first year, it is 95 mm Hg.

Physical Examination

During the course of the physical examination, the following body systems should be scrutinized for abnormal findings (16). We refer the reader to the chapter on physical diagnosis (see Chapter 15) for a more complete discussion on the subject. Keep in mind that the physical exam findings should be correlated with the signs and symptoms of the various non-infectious and infectious causes of fever, as discussed.

Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat Conditions with this area that are accompanied by fever may be, for example, teething with an accompanying runny nose and dribbling. Herpes simplex ulcerations on the tongue and mucous membranes, aphthous ulcers, gingivitis, tonsillitis, and pharyngitis can also cause a fever. There may be otitis media, cervical adenitis, retropharyngeal abscess, or rheumatic fever.

Respiratory System With respect to this system, one must be aware of respiratory tract infections. In addition to fever, one must observe for the presence of cough and chills, signs of respiratory distress such as flared nostrils, tachypnea, and retraction of the supraclavicular, intercostal, and subcostal areas. Upon auscultation, observe for the presence of crackles and wheezes over the affected lobe. Chest radiography should be considered when there is evidence of lung consolidation. The spine is also scrutinized on the PA chest/AP thoracic radiograph (see Chapter 4).

Gastrointestinal System In the case of gastrointestinal involvement there may be, in addition to fever, abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. One must consider food poisoning, acute appendicitis, and peritonitis. In those cases, laboratory tests are helpful.

Integumentary System One must be aware of dermatological manifestations that are accompanied by lever. These involve, for example, viral infections resulting in measles, mumps, and chicken pox.

Nervous System With respect to this system, one must be aware of certain conditions that require emergency care. These include subdural hematoma caused by trauma (see Chapter 16), encephalitis, and meningitis (see Chapter 12). With respect to screening for infants who are at low risk for serious bacterial infection, we remind the reader to review the characteristics of the toxic child, particularly lethargy. Figure 17-1 depicts an overview of some of the physical examination findings in an acutely febrile child.

The findings from the history and physical examination of the child should assist in determining when or if the patient may need to be referred for additional care. The authors propose the following criteria for referral:

The infant is younger than 2 months of age and the child’s temperature exceeds 100.4°F (38°C).

The fever persists for several days at at 104°F (40°C) to 104.9°F (40.5°C).

There is a positive Kernig’s or Brudzinski’s sign.

The child has febrile seizures that last longer than 15 minutes.

There is an acute airway obstruction (e.g., acute epiglottitis or retropharyngeal abscess). There may be stridor, drooling, retractions, and maintenance of the head and neck in the “sniffing position” (the neck is slightly flexed and the head is slightly extended on the neck and held quite still).

Cardiorespiratory compromise (e.g., severe pneumonia and pericarditis) including dyspnea, cyanosis or pallor, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypotension.

Laboratory and Radiographic Examinations

Most fevers are self-limiting and resolve in a few days, requiring very little in terms of sophisticated diagnostic tests or specific therapy. Supportive measures are indicated. In cases of persistent fever it is important to realize that more detailed examinations will be required to allow for an accurate diagnosis. Laboratory examination can begin with urinalysis and/or culture. Hematology will also need to be considered, including a full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and any cultures. Radiologic examination of the chest and/or any area that may have sustained a trauma may be needed. In addition to the general types of examinations described above, specific tests such as a bone marrow biopsy (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma) and the Mantoux test for the detection of tuberculosis may be required for the differential diagnosis.

Medical Management

Medical management of febrile infants and children is commonly based on the 1993 guidelines by Baraff et al. (18). In this study, an expert panel of individuals in pediatrics, infectious diseases or emergency medicine examined the scientific literature to develop guidelines for the care of infants and children from birth to 36 months of age with fever without a known source. For brevity of discussion of the guidelines, the definition of low-risk febrile infants and toxic appearing infants and children must first be presented.

Definition of Low-Risk Febrile Infants The criteria for low-risk febrile infants includes previously healthy, absence of a focal bacterial infection upon physical examination, and negative results of laboratory screening. Negative laboratory screening is defined as WBC count of 5,000 to 15,000/mm3, <1,500 bands per cubic millimeters, normal urinalysis, and, if diarrhea is present, <5 WBCs per hpf in the stool.

Toxic Appearing Infants and Children

Toxic appearing is defined as a clinical picture consistent with the sepsis syndrome. This is characterized by lethargy, signs of poor perfusion, or marked hypoventilation, hyperventilation, or cyanosis. Lethargy is further defined as a level of consciousness characterized by poor or absent eye contact, failure of the child to recognize parents, or failure of the child to interact with persons or objects in the environment.

Medical Management Options by Age Group

The medical management options for a febrile child are dependent on and categorized according to age: infants younger than 28 days old, 28 to 90 days old, and 3 to 36 months of age.

Infants Younger than 28 Days Old There are two management options for infants in this category. All febrile infants should have a sepsis evaluation and be hospitalized for parenteral antibiotics while waiting for the laboratory results. The sepsis evaluation includes cerebrospinal fluid (for cells, glucose, and protein), blood (complete blood cell and differential

count), and urinalysis. The second option for low risk infants is hospitalization, sepsis evaluation, and careful observation without parenteral antibiotics.

count), and urinalysis. The second option for low risk infants is hospitalization, sepsis evaluation, and careful observation without parenteral antibiotics.

Infants 28 to 90 Days Old The management of infants in this category is further delineated based on those children that are low-risk or not at low-risk.

Low-Risk Infants There are two management options for infants in this category: outpatient management with blood and urine cultures and an intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone or outpatient observation without antibiotic therapy.

Non-Low-Risk Infants The management option for infants in this category is sepsis evaluation and hospitalization for parenteral antibiotics while waiting for the laboratory results.

Children 3 to 36 Months Old For previously healthy children in this category, the management options involve the following:

Child appears toxic: admit for hospitalization, perform sepsis workup, and administer parenteral antibiotics.

The child does not appear toxic and does not have a fever ≥102.2°F (39°C). This child should receive outpatient observation without antibiotic therapy or diagnostic tests. Acetaminophen is recommended at 15 mg/kg per dose every 4 hours for fever. The child is returned to the hospital if the fever persists for longer than 48 hours or the child’s clinical condition deteriorates.

The child does not appear toxic but has a fever ≥102.2°F (39°C). For the child in this category, the following management considerations are recommended. Urinalysis for boys younger than 6 months of age and girls younger than 2 years of age. Stool culture for those with blood and mucus in their stool or ≥5 WBCs per hpf in the stool. A chest radiograph is recommended if the patient presents with dyspnea, tachypnea, rales, or decreased breath sounds. A blood culture is recommended for all receiving antibiotic therapy as well as acetaminophen at 15 mg/kg per dose every 4 hours for fever. A follow-up is recommended in 24 to 48 hours. If the blood culture is positive, admit for sepsis evaluation and parenteral antibiotics. If the urinalysis is positive, the patient is admitted if they are febrile or appear ill. If the child is afebrile and well, outpatient management with antibiotics is the recommended treatment.

Parental Considerations

The association of fever with serious illness may lead parents to “fever phobia” (19) and overreaction, resulting in mismanagement or unnecessary visits to the doctor. This mismanagement is not without its consequences, as indicated by concerns regarding aspirin poisoning (20) and acetaminophen overdosage (21). In addition to the management considerations discussed above, the following should be brought to the parents’ attention (22):

Though fever may signal the need for a doctor’s attention, the fever itself is rarely harmful and is a sign that the child is fighting the disease.

Place more emphasis on changes in the child’s behavior than the thermometer readings.

Before taking the temperature, the mercury thermometer should be shaken to below 95°F (35°C).

Children younger than 5 years of age should have their temperature taken rectally. The thermometer should be well lubricated, inserted into the rectum carefully approximately 1 in., and held in place for 2 to 3 minutes.

Children older than 5 years of age should have their temperature taken orally. The thermometer should be placed under the child’s tongue with prior instructions to purse his or her lips around the thermometer, not to bite down, and to breathe through the nose.

If the child’s temperature is 100.4°F (38°C) to 102.2°F (39°C), the medical recommendation is to give him or her acetaminophen in the recommended dosage and ensure plenty of fluid intake; do not overheat with clothing or blankets and reassess the child’s temperature every 4 hours.

If the child’s temperature is ≥102.2°F (39°C), the medical treatment recommendation is acetaminophen, as discussed above. After 1 hour, if the fever persists, sit the child in a tub of lukewarm water and sponge-bath him or her for 30 minutes, even if he or she shivers or cries; if the fever persists 4 hours after giving acetaminophen, continue giving it at 4-hour intervals and continue observing the child.

The child should be referred to a medical physician if the child has a fever and if any of the following apply:

The child is younger than 3 months of age.

The child’s fever exceeds 100.4°F (38°C) for more for more than 24 hours (and is unresponsive to conservative measures).

The child’s face, arms, and legs are twitching.

The child is irritable or drowsy even without medication.

The child complains of belly ache, ear ache, or pain on micturition.

The child is vomiting, suffering from diarrhea, wheezing, or has difficult breathing.

Febrile Seizures

The febrile seizure occurs usually between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. The seizure (tonic-clonic response)

is preceded by a quick onset of increased body temperature. The fever range is typically between 100.4°F (38°C) and 105.8°F (41°C). The seizures may last up to 15 minutes and normally only one seizure occurs. It should be noted that 1% to 2% of these seizures may go beyond 15 minutes. This duration is extremely dangerous for the child and warrants immediate emergency care. Seizures that go beyond 60 minutes may cause severe brain damage as a result of hypoxia.

is preceded by a quick onset of increased body temperature. The fever range is typically between 100.4°F (38°C) and 105.8°F (41°C). The seizures may last up to 15 minutes and normally only one seizure occurs. It should be noted that 1% to 2% of these seizures may go beyond 15 minutes. This duration is extremely dangerous for the child and warrants immediate emergency care. Seizures that go beyond 60 minutes may cause severe brain damage as a result of hypoxia.

Fever of Unknown Origin

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is defined as a persistent fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or more for more than 3 weeks without underlying obvious disorder or etiology after an inpatient evaluation (23). DiNubile (24) notes another type of FUO—an acute form—which arises more frequently in children. He proposes that this entity be called an “acute fever of unknown origin” and cautions against using antibiotic therapy in most stable immunocompetent patients.

CASE MANAGEMENT

The optimal treatment strategy for a child presenting with FUO remains a controversy. The child who presents with fever may be at risk for a serious bacterial infection and may develop serious complications, such as meningitis or pneumonia. Therefore, the treatment of a child who presents with FUO typically consists of hospitalization, empiric antibiotic treatment, and further diagnostic testing (25). However, other clinicians disagree with the above treatment option and elect a more selective “conservative” approach, such as outpatient management with or without antibiotics but with close observation (26). The treatment option is dependent on the risk of complications from serious infection traded off against the risks and costs of hospitalization, unnecessary antibiotics, and laboratory testing. Certain studies clearly indicate that a strictly defined low-risk group of febrile infants can be cared for at home safely and effectively without the administration of antibiotics, but this form of management should be used only after a complete laboratory evaluation for sepsis and after clinical assessment of the infant by an experienced clinician (27). On the other hand, numerous studies evaluating the role of laboratory tests and clinical judgment in identifying children at risk for serious complications have shown that as many as 23% to 50% of serious cases are not identified by such methods (18,28,29,30,31). If risk factors are not present and the fever seems to be viral in origin, extensive diagnostic testing (e.g., hematology) is not needed unless the fever becomes persistent or escalates to an unsafe level.

Although the identification of a specific diagnosis is sometimes difficult, even for the most seasoned clinician, it is important always to attempt to identify those children at risk for a serious bacterial infection (e.g., meningitis). For the treating clinician, the Rochester Criteria as outlined above should be considered. Jaskiewicz et al. (12) performed a prospective study of 1,057 eligible infants to test the hypothesis that infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infections can be accurately identified by the low-risk criteria of the Rochester Criteria. They found that among wellappearing febrile infants, the Rochester Criteria may be applied to determine those infants who are unlikely to have serious bacterial infection. The child should be brought in for emergency care if he or she is (a) lethargic, has a seizure, or a stiff neck, (b) 3 months old and has a fever ≥100.4°F (38°C), or (c) the parent is anxious (32). Infectious causes of fever include those from viral, bacterial, protozoan, or rickettsial sources. These infectious agents are most likely to cause a disease process in the immunocompromised patient. Noninfectious causes of fever include various drugs; trauma (spinal or otherwise); teething; dehydration; heat stroke; poisoning; neoplastic disorders (e.g., lymphomas, leukemia, neuroblastoma, reticulum cell sarcoma, Wilm’s tumor); inflammatory disorders (e.g., regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis), endocrine disorders (e.g., hyperthyroidism, virilizing adrenal hyperplasia); infantile cortical hyperostosis (Caffey’s disease); allergies; central nervous system (CNS) fever (i.e., altered thermostat); and collagen vascular disorders (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa, polymyositis, Kawasaki disease, Stevens Johnson syndrome, systemic lupus erthythematosis) (7,33,34,35,36).

Noninfectious Causes of Fever

Trauma Physical trauma can cause a child to develop a fever. There should be a history of trauma. The overlying skin may show bruises or swelling. This may be accompanied by underlying pain or bone fracture. It is important to notify Child Protection Services if child abuse is suspected (see Chapter 16). The physical trauma (e.g., subluxation, fracture) is treated according to the specifics of the case (See Chapters 5 and 23).

Teething Normal childhood teething can cause fever. The patient may have swollen and tender gums. There may also be manifestations of gastroenteritis such as vomiting and/or diarrhea. The resistance of the child may be lowered, leading to recurrent or persistent viral or bacterial infections. The mother can have difficulty feeding the child and anorexia may develop.

Dehydration Dehydration caused by common factors such as poor fluid intake or exercise can also

result from gastroenteritis. Signs and symptoms of dehydration include fever, loss of skin turgor, thirst, reduced urinary output, soft sunken eyes, fontanelle (if present) depression, prominent skull sutures, increased pulse rate, diminished pulse volume, dry mouth, diminished tearing, lethargy, orthostatic hypotension (among older children), and cool pale skin. Laboratory findings include elevated hematocrit value, diminished renal functions and electrolyte imbalances (Na+ and K+). Treatment is rehydration therapy with correction of the electrolyte imbalance.

result from gastroenteritis. Signs and symptoms of dehydration include fever, loss of skin turgor, thirst, reduced urinary output, soft sunken eyes, fontanelle (if present) depression, prominent skull sutures, increased pulse rate, diminished pulse volume, dry mouth, diminished tearing, lethargy, orthostatic hypotension (among older children), and cool pale skin. Laboratory findings include elevated hematocrit value, diminished renal functions and electrolyte imbalances (Na+ and K+). Treatment is rehydration therapy with correction of the electrolyte imbalance.

Drug Fever The fever is usually persistent in this syndrome. Essentials for diagnosis include a history of drug intake, which may be accompanied by skin eruptions. Common drugs that can lead to this reaction are aspirin, penicillin, and sulfonamides. Reactions to a single injection, for example, depot penicillin, can last for months. Treatment is through discontinuance of the offending drug. Symptomatic treatments are usually very effective.

Regional Enteritis Regional enteritis is an acute inflammation of the lining of the intestine accompanied by fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. Treatment is supportive and includes fluid replacement.

Neoplastic Disorders

Hodgkin Lymphoma This disease is more common in older children (i.e., adolescent age). Lymphadenopathy (firm, rubbery, non-tender) often involving the cervical nodes may be present. Hepatomegaly can occur with or without splenomegaly. The fever is intermittent (Pel-Epstein). There may also be night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, and generalized pruritus. Pain is present at the site of the nodes upon ingestion of alcohol.

The blood laboratory tests may reveal anemia, leucocytosis or leucopenia, thrombocytosis, or thrombocytopenia. Eosinophilia may be present. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, and serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (hepatic involvement) should be checked.

A Gallium scan can show the site of involvement. Lymph node biopsy will establish the diagnosis. Bone marrow biopsy and computed tomography (CT) scans may also be used to establish the diagnosis/prognosis. Laparotomy and splenectomy are often performed. Chest x-ray may show parenchymal or mediastinal nodal disease. Lymphangiography shows “foamy” filling defects in enlarged nodes.

Complications include susceptibility to herpes zoster and fungal infections. Treatment can lead to acute toxicity (e.g., nausea, vomiting, anorexia, alopecia, bone marrow suppression, radiation disease, pneumonitis, and an increased incidence of second malignant tumors such as acute myelogenous leukemia, which is a fatal complication).

Because of the splenectomy, there is increased susceptibility to infection, especially pneumococcal pneumonia. Medical treatment is combined chemoradiotherapy according to the stage of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Clinical Staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma Stage I disease is confined to one group of nodes. In stage II, disease findings are present in more than one group of nodes but is limited to one side of the diaphragm. Stage III disease involves nodes on both sides of the diaphragm with splenomegaly. In stage IV there is hematogenous spread to the liver, bone marrow, lungs, etc.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Non-Hodgkin lymphoma afflicts more boys than girls. It is also more common in the lymphoid structures of the intestinal tract, usually in the ileocecal area. Involvement of the CNS produces symptoms caused by cord compression or increased intracranial tension.

Laboratory findings are similar to Hodgkin lymphoma except that the “routine” laparotomy and splenectomy are not done. Lumbar puncture with cytologic examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) needs to be done on all patients. Medical treatment is with combined chemo-radiotherapy.

Leukemia

Symptoms and Signs Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common form of leukemia. Other types include acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia and chronic myelocytic leukemia.

There is an increased incidence in children with Down’s syndrome or in rare familial diseases as ataxia telangiectasia, Bloom’s syndrome, Fanconi’s anemia, Kleinfelter’s syndrome, and neurofibromatosis. The Epstein Barr virus is implicated in Burkitt’s leukemia and lymphoma. In the early stages of leukemia, fever may be present. Other symptoms include headache, pallor, fatigue, irritability, and palpitation. Anemia is present. The patient easily bruises and epistaxis or gum bleeding may be present. Increased susceptibility to infections may develop, leading to toxemia and septicemia. Bone and sternal tenderness and nuchal rigidity are musculoskeletal signs during later stages. Blurring of vision from increased intracranial tension can develop.

Laboratory findings include anemia (normochromic, normocytic), thrombocytopenia, and leucocytosis with neutropenia or even leucopenia. Lymphocytosis may be present with or without blast cells in the peripheral blood. Bone marrow biopsy will show the replacement of the normal marrow with malignant cells. Metabolic

abnormalities include hyperuricemia, renal failure, and increased lactic acid dehydrogenase.

abnormalities include hyperuricemia, renal failure, and increased lactic acid dehydrogenase.

The chest x-ray is used to evaluate for a mediastinal mass or hilar adenopathy and for pulmonary infiltrations suggestive of infection. Ultrasound may be used to assess splenomegaly or renal enlargement suggestive of leukemic infiltration.

Patient Management The optimal medical drug therapy is not yet known and still investigational. Most often, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are combined. Bone marrow transplantation is the treatment of choice.

Neuroblastoma Neuroblastomas are of neural crest origin and may arise anywhere along the sympathetic ganglion chain or in the adrenal medulla. It is the most common tumor in children younger than 1 year of age in the United States.

Symptoms and Signs Fifty percent of patients present with manifestations of metastasis. Any of the following may be present: abdominal mass; weight loss; anemia; failure to thrive; abdominal pain and distention; fever; bone ache; diarrhea; hypertension (in 25% of cases); Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, meiosis, enophthalmos, heterochromia of iris); orbital ecchymosis; dysphagia; paraplegia; cauda equina syndrome; flushing; sweating irritability; and cerebellar ataxia.

CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest, neck, abdomen, or pelvis (depending on location of the tumor) is required for diagnosis. Laboratory findings may show anemia and thrombocytopenia. Chest x-ray, bone marrow aspiration, and renal function tests are additional diagnostic tools.

The staging of neuroblastoma presented is that of Evans:

Confined to single organ, completely resected

Extends beyond organ of origin but does not cross midline

Extends across midline

Distant metastasis

Infants younger than 1 year with metastasis to liver, skin, or bone marrow, sparing cortical bone.

Patient Management Treatment is according to the stage of the disease and can be in the form of surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or bone marrow transplantation.

Wilm’s Tumor Wilm’s tumor is an embryonal renal neoplasm containing blastoma, stromal, or epithelial cell types; it usually affects children younger than 5 years of age.

Symptoms and Signs Most patients are asymptomatic. If symptoms develop, they take the form of fever and abdominal pain. There may be a palpable upper abdominal mass. Other signs include cardiac murmurs, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, prominent abdominal wall veins, varicocele, gonadal metastasis, and, rarely, signs of an acute abdomen with free intraperitoneal rupture.

In addition to anemia (low complete blood count), urine analysis may reveal hematuria. The chest x-ray and abdominal scout views may reveal calcifications. Additional imaging includes the CT scan and contrast studies of the chest and abdomen. Biopsy is also used.

Patient Management Treatment usually is with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Other supportive measures are recommended.

Caffey’s Syndrome (Infantile Cortical Hyperostosis)

This is a benign disease of unknown cause occurring before 6 months of age. Fever is a symptom. Non-suppurative, tender, painful swellings that can involve any bone in the body and are frequently widespread develop. The mandible and clavicle are affected in 50% of cases. The ulna, humerus, and ribs may be affected as well. The disease is limited to the shafts of bones and does not involve subcutaneous tissues or joints. It is self-limiting but may persist for weeks or months. Laboratory findings include anemia, leukocytosis, and high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum alkaline phosphatase. Radiographs show the lesions.

Polyarteritis Nodosa Polyarteritis nodosa is a collagen-vascular disorder. A vasculitis of mediumsized arteries with fibrinoid degeneration in the media extending to the intima and adventitia leads to aneurysmal dilation of the vessels and thrombus formation with organ infarctions in addition to fibrosis of the vessels. There is no known cause, but immunological involvement is suspected.

Symptoms and Signs The clinical picture includes fever, weakness, weight loss, malaise, myalgia, livido reticularis, headache, and abdominal pain. The following may be present in multisystem involvement:

Musculoskeletal: myalgia, migratory arthralgia, and arthritis

Skin: purpura, urticaria, subcutaneous hemorrhages, polymorphic rashes, subcutaneous nodules, Raynaud phenomena

Gastrointestinal: recurrent and severe pain, hepatomegaly nausea, vomiting, and bleeding

Lung: hilar adenopathy, patchy infiltrates, reticular or nodular lesions (often fleeting)

Renal: hypertension, hematuria, proteinuria, progressive renal failure

CNS: seizures, confusion, headaches

Peripheral nervous system: monomuritis multiplex

Cardiac: pericarditis, congestive heart failure associated with hypertension, and/or myocardial infarction

Genitourinary: usually asymptomatic but may have testicular, epididymal, ovarian pain

A complete blood count may reveal neutrophilia, eosinophilia (rare), and anemia. Elevated ESR and hypergammaglobulinemia may be present. Biopsy of involved vessels can be done (very specific test).

Patient Management Treatment is supportive. The patient should decrease salt in the diet if the condition is associated with hypertension. Medical interventions include prednisone and cyclophosphamide. Plasmapheresis may also be added.

Dermatomyositis (Polymyositis) This is a systemic connective tissue disease characterized by inflammatory and degenerative changes in muscles sometimes accompanied by a characteristic skin rash. It is of unknown etiology. Cell-mediated autoimmunity viruses may be a possible participating factor.

Symptoms and Signs The clinical picture includes difficulty when arising from sitting or lying positions; difficulty kneeling; difficulty climbing stairs; difficulty raising arms; joint pain/swelling; dysphagia; buttock pain; respiratory impairment; symmetrical proximal muscle weakness; decreased deep tendon reflexes; muscle swelling; stiffness and induration; rash over the face (eyelids, nasolabial folds), upper chest, and dorsal hands; and periorbital edema.

Laboratory findings may show increased creatinine phosphokinase, increased aldolase, increased serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, increased lactic acid dehydrogenase, myoglobinuria, increased ESR, positive rheumatoid factor (in fewer than 50% of patients), leukocytosis, anemia, hyperglobulinemia, and increased creatinine.

Patient Management Supportive measures (e.g., nutrition, psychological counseling, and chiropractic care) should be instituted. Medical treatment is with prednisone or azathioprine or methotrexate.

Kawasaki’s Disease (Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome) The clinical features of this disease are erythema of the conjunctivae and mucous membranes, a maculopapular rash with subsequent desquamation, and dominant lymphadenopathy of the anterior cervical chain. Fever may be present as well. Bilateral conjunctival injection, truncal rashes, palmar erythema, and non-pitting edema of the hands and feet may be present. There is firm skin overlying the lesion, and desquamation takes place 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of the disease, beginning in the extremities and progressing centrally. There may an injected pharynx, dry fissured lips, and a strawberry tongue.

Symptoms and Signs The following are relatively common findings: cervical lymphadenopathy, pneumonia, diarrhea, arthralgia, arthritis, photophobia, tympanitis, meatitis, meningitis, and carditis. Less common features may include severe abdominal pain, hydropic gall bladder, cardiac tamponade, congestive heart failure, pericarditis, myocarditis, coronary artery thrombosis, aneurysm of the cardiovascular system, febrile convulsions, pleural effusions, tonsillar exudate, encephalopathy, jaundice, and renal abnormalities.

Leucocytosis, anemia (mild), thrombocytosis, and an increased ESR may be present. Urinalysis may reveal phoria or proteinuria. The CSF may reveal an increase in the number of cells. There may either be normal or elevated serum immunoglobulin (Ig) and complement levels. Liver involvement is indicated by elevated transaminase activity. The electrocardiogram may show changes.

Patient Management No scientifically proven treatment has been established. In addition to supportive measures, symptomatic treatment to improve the clinical features, for example, aspirin for fever, or treatment of underlying congestive heart failure may be needed.

Stevens Johnson Syndrome Stevens Johnson syndrome is characterized by conjunctivitis, stomatitis, and balanitis. The skin lesions vary from small papules to extensive bullae. The oral cavity is involved in 50% of cases. The lips are often covered with hemorrhagic exudate. Erythematous plaques on the mucosa may develop into vesicles or bullae that subsequently rupture, forming shallow erosions covered by a pseudomembrane. These lesions may become infected secondarily. The etiology is unknown but may be secondary to a drug reaction or occur after a upper respiratory tract infection.

Treatment of mild illness is with local mouth wash and antihistamines. In severe illness systemic corticosteroids are often used.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus The following symptoms and signs can occur in SLE: fever, arthritis, myalgias, skin lesions, malar (butterfly) rash, oral ulcers, anorexia, malaise, eye pain and/or redness, chest pain and/or shortness of breath, pallor, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle tenderness, aching and stiffness, headaches and visual problems, and psychosis/delirium.

Laboratory tests show a positive antinuclear antibody and/or an anti-double standard DNA, and/or Anti-Sm, and/or false positive VDRL, and/or positive lupus erythematosus preparation. These tests have either a high sensitivity (antinuclear antibody, false positive VDRL) or specificity (anti-double standard DNA, anti Sm, and lupus erythematosus preparation) and are included as American Rheumatology Association criteria for the diagnosis of SLE along with the clinical features. Other laboratory findings and positive tests may include an increased ESR; anemia; leukopenia; lymphopenia; abnormal urinary sediment; proteinuria; increased prothrombin time; hypoalbuminemia; positive anticardiolipin; thrombocytopenia; increased serum creatinine; positive Coombs test; complement levels (cryoglobulins, Raji cell test, CLq precipitins); coagulation studies (lupus anticoagulant); biopsy of skin, kidney, and peripheral nerves; cerebral angiography; chest x-ray; magnetic resonance imaging; and an echocardiogram.

Adjustments or manipulation is contraindicated at joints exhibiting signs of laxity/hypermobility. Medical treatment consists of steroidal treatment for skin lesions; minor arthritis is treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and severe disease is treated with immunosuppressants.

Infectious Causes of Fever

Infectious causes of fever include influenza, mumps, measles and other viral agents and bacterial organisms (33,34,35,36).

Influenza Influenza is caused by a virus droplet infection in a susceptible host.

Symptoms and Signs An abrupt onset of high fever may be accompanied by toxic-appearing manifestations. This upper respiratory tract illness is in the form of a runny nose, cough, and difficulty breathing. In infants it may be associated with croup.

Pharyngeal or nasal secretion can be examined with fluorescent-labeled antibody for rapid identification of the influenza virus. Serum antibody obtained early and late in the course of infection can be of value in retrospective diagnosis. Radiographic findings reveal extensive bronchial pneumonia or simply hyperaeration.

Reye’s Syndrome and Other Complications Reye’s syndrome is an encephalopathy with fatty degeneration of the viscera that occurs in children receiving aspirin (salicylates) during acute influenza infections. Clinically it can be suspected when an upper respiratory tract infection is followed by excessive vomiting and convulsions; later it may be further complicated by liver dysfunction and hypoglycemia. It is absolutely contraindicated in all children (including adolescents) to ingest aspirin during an influenza infection.

Influenza may progress in rare cases (susceptible individuals) to pneumonia, croup, cardiac arrest, emphysema, pneumothorax, and Reye’s syndrome.

Patient Management Supportive measures include proper hydration, nutrition, and rest. Supplements that support immune function include vitamins A, C, and E and zinc. Chiropractic care is indicated at sites of subluxation. Certain herbs (e.g., echinacea) may be helpful.

Medical referral is required in severe cases where the airway needs to be supported. Tracheotomy may be needed. If respiratory or cardiovascular complications develop, these are treated medically.

Parainfluenza Viral Infection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree