FIGURE 2-1 A 6-month-old male infant with syndactylies of the first, second, and third web spaces.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What causes syndactyly?

- How common is it?

- Are there any associated syndromes or conditions?

- How is it classified?

- What are the indications for surgical treatment?

- When should surgery be performed?

- What are the surgical principles and techniques for syndactyly?

- What are the results of surgical treatment?

- What complications may occur with surgical care?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Hand function is dependent upon independent digital motion. Supple web spaces allow for flexion, extension, and abduction during all activities of daily living, particularly in the keyboard-driven society we live in today.

Syndactyly, or “webbed fingers,” is thought to be one of the most common congenital hand differences presenting to pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeons. Given the limitations of independent digital function, as well as aesthetic differences, surgical treatment is typically recommended in patients with congenital syndactyly

Etiology and Epidemiology

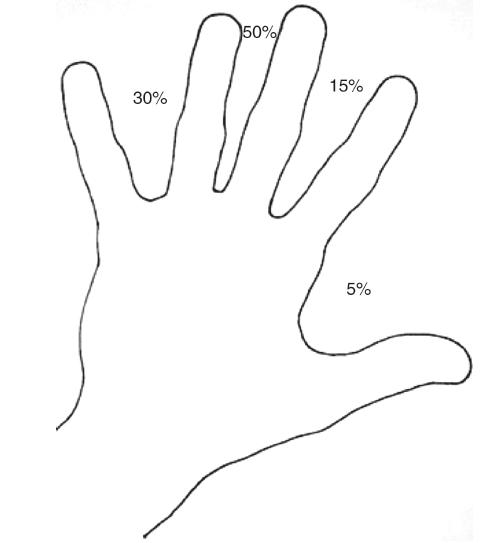

Simple syndactyly occurs in approximately 1:3,000 live births.1,2 Males are affected more commonly than females, and Caucasians more than Blacks or Asians. Inheritance pattern is thought to be autosomal dominant with variable expressivity and variable penetrance, though sporadic cases are quite common. Often bilateral, the feet and toes may also be involved. In general, the third web space is most commonly affected, followed by the fourth, second, and first web spaces. The pneumonic “5-15-50-30” may be used to remember the frequency of web-space involvement from first to fourth (Figure 2-2).

FIGURE 2-2 Schematic diagram depicting the prevalence of web-space involvement in cases of simple and complex syndactylies.

Syndactyly results from a failure of differentiation. During upper limb development, the hand segment forms as a “paddle” at roughly the fifth week of gestation. Interdigital clefts are created via apoptosis, mediated by the apical ectodermal ridge and proceeding in a distal-to-proximal fashion. Failure of proper or complete interdigital separation leads to syndactyly and explains the clinical phenotypes commonly encountered. Efforts continue to characterize the genetic and molecular mechanisms behind syndactyly.3 In cases of autosomal dominant syndactyly, candidate regions have been identified on the second chromosome (2q24–q36).1 Other variations of syndactyly have been linked to mutations in the HOXD13 gene, also located on chromosome 2.4,5

Clinical Evaluation

You can observe a lot just by watching.

—Yogi Berra

Understanding of normal digital web-space anatomy is necessary to evaluate abnormal situations. Typically, the index-long and ring-small finger commissures are U shaped, while the long-ring web is V shaped. The non-glabrous skin of the normal web space is sloped approximately 45 degrees from proximal-dorsal to distal-volar, extending to roughly the midpoint of the proximal phalanx. The natatory ligaments (or superficial transverse metacarpal ligament) help form the web contour and join adjacent lateral digital sheets. This supple skin and soft tissue complex allows for interdigital abduction of up to 35 and 70 degrees of abduction between the thumb and the index.6

Normally, each digit receives its vascularity in part via a radial and ulnar digital artery, which arises from the bifurcation of the common digital arteries. However, of critical surgical importance is the fact that the bifurcation of the digital arteries and nerves may be abnormally distal in cases of syndactyly.

The diagnosis of syndactyly is not subtle, and the extent of digital involvement (i.e., incomplete vs. complete) is readily apparent on clinical inspection. More careful observation will typically distinguish between cases of simple, complex, and complicated syndactylies. The presence of passive and active interphalangeal (IP) joint motion with well-formed flexion and extension creases implies normal joint anatomy and is consistent with simple syndactyly. In patients where creases are absent and IP joint motion is absent, complex or complicated syndacty-lies should be suspected.

Standard plain radiographs of the affected hand will confirm the presence of fused bony elements and any other associated anomalies. In cases of syndactyly associated with other clinical syndromes, such as Poland, Apert, or amniotic band syndrome, evaluation of the entire upper extremity, chest, feet, and head/face will reveal other abnormalities.

Syndactyly is classified according to the extent of digital involvement and the character of the tissue involved. “Complete” syndactyly extends to the digital tips, whereas “incomplete” syndactyly ends proximal to the fingertips. “Simple” syndactyly refers to digits connected only by skin and soft tissue. The nail plates may or may not be fused. “Complex” syndactyly denotes bony fusions between adjacent phalanges. “Complicated” syndactyly refers to the interposition of accessory phalanges or abnormal bones between digits. In simple syndactyly, the joints, ligaments, and tendons of the affected digits are usually normal.

Surgical Indications

There are really only two plays: Romeo and Juliet, and put the darn ball in the basket.

—Abe Lemons on basketball

Surgical release is recommended in all but the most mild of incomplete syndactylies. While indications for surgery are clear, controversy continues to surround issues related to the timing and technique of separation. Indeed, the question is not “whether to do surgery” but often “when” and “how” to do it.

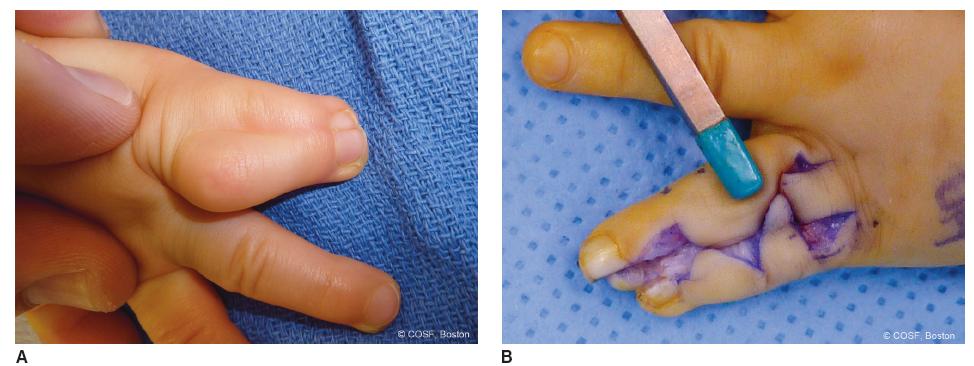

Timing of surgery remains controversial and must be determined on an individual patient basis. Flatt has previously written: “I believe one should ask not how soon the operation can be done but rather how late the functional demands of the hand will allow postponement of surgery.”7 In general, surgical release of simple complete syndactylies of the second or third web spaces may be safely and appropriately delayed until 18 months of age with no adverse effect on hand function or fine motor development.8–10 Advantages of later surgery include operating on a hand after much of the subcutaneous fat has involuted, allowing for easier mobilization of skin flaps and greater coverage. In addition, the hand will roughly double in size during the first 3 years of life; operating on a hand after more of this growth has occurred will minimize the complications of web creep and clinically significant scar contractures. Earlier surgery is recommended for the border digits, as syndactylies of digits of disparate length will result in flexion and angular deformities if left unattended (Figure 2-3). In these cases, surgery may be initiated at 9 months of age. Currently our preference is to perform syndactyly releases of the second and third web spaces at 12 to 18 months of age, with earlier releases of the thumb and small finger for the reasons described above.

FIGURE 2-3 Deformity secondary to syndactyly of border digits. A: Clinical photograph of a fourth web simple complete syndactyly. Note is made of flexion and angular deformity of the ring finger, due to the tethering effect of the small finger. B: After surgical release, the ring finger is easily extended, and longitudinal alignment is restored.

Contraindications to surgical release are few. First and perhaps most importantly, great caution should be taken when attempting to release a “super digit.”11 This term is used to describe a large digit supported by two metacarpals (type I) or syndactylized digits supported by a single meta-carpal (type II). Although surgical separation may be technically feasible, this often results with angular deformity and loss of motion in the separated digits, leading to compromised hand function. Indeed, the presence of a single, functioning, though aesthetically different super digit is preferred over two separate, stiff, crooked, nonfunctioning digits. The second contraindication to surgical release applies to cases of complex synpolydactyly, in which multiple conjoined digits (or bony elements) are fused yet move and function as one. Again, while technically feasible, surgical release may result in compromised hand function due to the unpredictability of motion and alignment postoperatively.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Perhaps the single most important element in mastering the techniques and tactics of racing is experience. But once you have the fundamentals, acquiring the experience is a matter of time.

—Greg Lemond

While techniques of separation vary, a number of general surgical principles apply to almost all syndactylies. First, digits of differing lengths should be released early to prevent deformity and growth disturbance of the affected digits. Second, both sides of a single digit should not be operated upon at the same time to avoid vascular embarrassment. Third, local vascularized skin flaps should be used to re-create the commissure to avoid scar contracture and “web creep.” Fourth, interdigitating zigzag lateral flaps should be created to avoid longitudinal scar contracture. Fifth, judicious defatting of the skin flaps should be performed to facilitate skin closure, reduce tension across the flaps, and improve the aesthetics of the reconstructed fingers.12 And finally, full-thickness skin grafts are typically utilized to cover “bare areas” after syndactyly release.

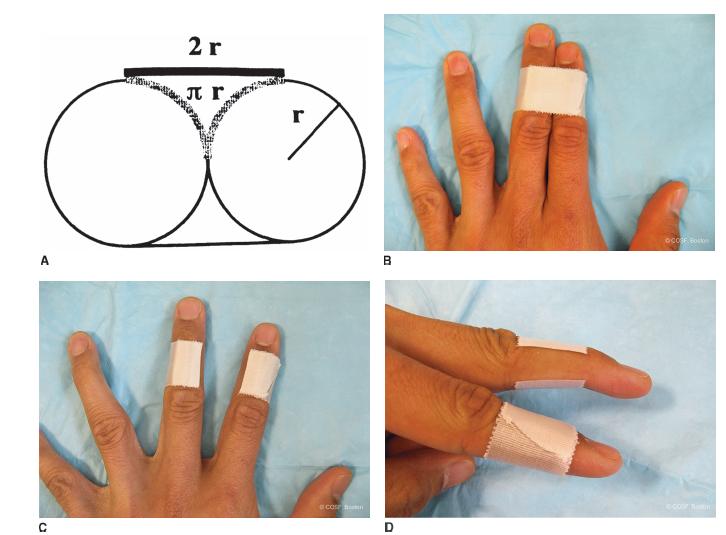

In cases of simple complete syndactyly, the combined circumference of the separated digits is 22% greater than the circumference of the syndactylized digits.7 While the need for full-thickness skin grafting is accepted by most hand surgeons, often this concept may be difficult for patients/families to understand. A simple demonstration may be performed in the office to illustrate the need for skin grafting (Figure 2-4).

FIGURE 2-4 Illustration of the need for skin grafting in syndactyly release. A: Schematic diagram depicting the difference in circumference of syndactylized (10.28r) versus separated (12.57r) digits. B: Clinically, this may be demonstrated to patients/families by taping two fingers together. C, D: After the fingers are separated by cutting the tape, the resulting defects will be easily seen.

Simple Syndactyly Release

Simple Syndactyly Release

Simple Incomplete

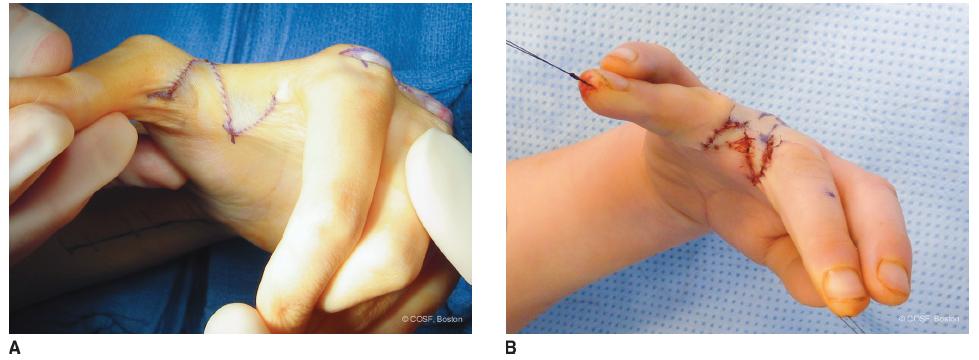

In patients with simple incomplete syndactylies where the distal web commissure is proximal to the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, simple skin rearrangement will provide adequate release with minimal morbidity Options in these cases include simple Z-plasties, four-part Z-plasties, double-opposing Z-plasties, or variations thereof 13–15 (see Sidebar). Our preference is to utilize two-or four-part Z-plasties for the first web space, and double-opposing Z-plasties for the second, third, and fourth web spaces (Figure 2-5). After the skin incisions are created, with care being made to ensure that all limbs are of equal length, the tourniquet is inflated and skin incised. Care is made to preserve full-thickness flaps to preserve vascularity. After release, flaps naturally rotate into place and are sewn in with 5-0 polyglactin (Chromic, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) interrupted sutures. A sterile bandage is applied, followed by a soft dressing or cast, depending upon the age of the patient.

FIGURE 2-5 A: Clinical photograph of the first web space after two-part Z-plasty. B: Clinical photograph after third web-space five-part Z-plasty.

Simple Complete

Patients are placed supine with the affected upper limb supported on a hand table. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed in the upper brachium, taking care to maintain access to the antecubital fossa, if full-thickness skin graft is to be taken from that site. If skin graft from the inguinal crease is to be harvested, the ipsilateral groin is also prepped and draped sterilely into the surgical field. Skin graft from the inguinal region should be taken well lateral to the palpated femoral pulse to minimize harvest of hair-bearing skin, and a surgical marking pen may be placed into the inguinal crease with the hip flexed to identify the most aesthetic axis from which to harvest skin; this will allow for easy primary closure of the harvest site with a scar that lies inconspicuously in the skin folds.

SIDEBAR

A Simple Approach to Z-Plasty

Z-plasty is a powerful tool in syndactyly surgery and other surgical procedures of the hand and upper limb. Given its wide applications, a fundamental understanding of the principles and techniques of Z-plasty is imperative.

While references to the use of Z-plasties date back to the 1800s, much of the mathematical modeling is attributed to Limberg.43,44 Although many modifications have been made, the fundamental principles are well established. Simple Z-plasties are named according to the length of the limbs and angle subtended by the limbs (Figure 2-6). Each limb is the same length, allowing for easy interchange of skin flaps. The central line lies in the axis in which lengthening is desired. The theoretical lengthening achieved by simple Z-plasties can be easily calculated with simple geometry (Figure 2-6).

In the example provided, a 60-degree Z-plasty is depicted with limbs of equal length, x. By dropping a vertical perpendicular line from one end of the Z-plasty to the other, two 30-60-90 triangles are created. Using the Pythagorean theorem, the length opposite the 60-degree angle is calculated. After the flaps are rotated, the previous horizontal distance x has now been increased to x times the square root of 3, approximately 1.732x. This simply explains the theoretical 75% increase in length obtained by a simple two-part 60-degree Z-plasty.

Simple two-part Z-plasties may be combined to increase their clinical applications. Z-plasties may be placed in series, to relieve acquired longitudinal scar contractures of the digits or tight circumferential skin associated with amniotic band syndrome (Figure 2-7). They may be expanded to form four-part or even six-part Z-plasties, such as are used for releases of simple first web-space syndactylies. Or they may be combined as double-opposing (or “kissing”) Z-plasties, as used in releases of simple incomplete syndactylies of the lesser digits (Figure 2-8). Note that in these circumstances, a “stem” is often placed on the Z-plasty to avoid flap tip necrosis and allow for easier flap rotation and insetting. All of these applications, however, are based upon the simple geometry of the simple Z-plasty.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree