FIGURE 40-1 Schematic diagrams depicting the (A) apprehension and (B) apprehension-relocation physical examination provocative maneuvers.

Classification of shoulder instability remains descriptive, based upon history, clinical examination, and radiographic findings. Traumatic instability remains the most common in children and adolescents, resulting from a single, identifiable inciting event. Not all traumatic instability, however, results in overt joint dislocation or need for manipulative reduction by an orthopaedic surgeon or emergency room physician. Indeed, a recent study suggests that traumatic subluxation, though subtle, may result in similar pathoanatomic lesions in the glenohumeral joint.16 Direction of instability similarly provides great insight into the failure of bony or soft tissue restraints, and provocative testing aids in characterizing the problem and predicting surgical findings.4 Indeed, 90% to 100% of traumatic anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations will result in anterior labral tears and Hill-Sachs deformities of the humerus.4,17,18 Conversely, multidirectional instability is typically atraumatic and is often seen in patients with repetitive overuse disorders, generalized ligamentous laxity, or systemic connective tissue disorders (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome).19,20

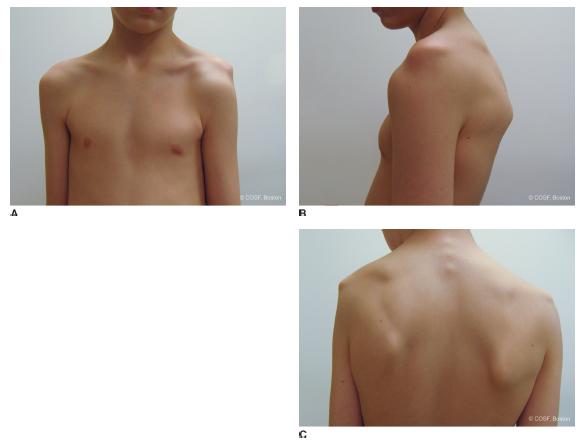

FIGURE 40-2 Clinical photographs of a patient with voluntary multidirectional instability of the left shoulder. A: Anterior glenohumeral subluxation. B: A prominent “sulcus sign.” C: View of the subluxed shoulder from the posterior aspect.

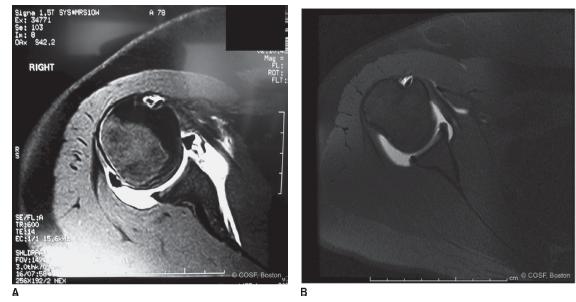

Radiographic evaluation begins with plain films of the shoulder. Anteroposterior and axillary views will confirm dislocation or reduction and detect obvious large bony lesions. MRI will provide additional insights into soft tissue injury involving the labrum, capsule, and surrounding structures (Figure 40-3). We favor the use of MR-arthrography, which may identify subtle injuries not seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed without intraarticular contrast; arthrography also assists in the assessment of capsular laxity, particularly during the evaluation of the patient with multidirectional instability.21

Surgical Indications

The indications for surgical treatment continue to evolve (see Coach’s Corner). In general, surgical stabilization procedures are indicated in patients with post-traumatic, recurrent, functionally limiting, or painful glenohumeral joint instability refractory to physical therapy and activity modification. There continues to be enthusiasm and ongoing research into the merits of surgery after a single instability event.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative Treatment

A pint of sweat will save a gallon of blood.

—General George S. Patton

Following the first traumatic instability event, nonoperative treatment is typically pursued. Following closed reduction of the glenohumeral joint, the shoulder is typically immobilized in a sling for comfort. There is no compelling evidence that prolonged sling immobilization of the shoulder in adductioninternal rotation for longer than what is needed for symptomatic relief lowers the risk of recurrent instability.

Recently, there has been increasing interest in immobilizing the shoulder in external rotation. The rationale is based upon the premise that external rotation immobilization may tension the anterior soft tissues, thus better reapproximating the torn or avulsed labrum to the glenoid rim. Itoi et al.22 have demonstrated via dynamic MRI studies that this may be accomplished. Indeed, in a preliminary case-control study and subsequent randomized controlled trial, the relative risk reduction of recurrent instability was 38% in patients treated with external rotation immobilization versus conventional internal rotation sling immobilization.23–25 The benefit of external rotation immobilization was higher in younger patients. Interestingly, others have not been able to reproduce this experience, suggesting that external rotation immobilization, while theoretically appealing, may not be applicable to all patients.26,27 Furthermore, external rotation immobilization requires a great deal of patient compliance, given the difficulties in performing everyday activities with the shoulder externally rotated 30 to 45 degrees for 4 weeks.

FIGURE 40-3 A: Axial MRI arthrography image of an anterior labral tear in the setting of traumatic anterior instability. B: Axial MRI arthrography image of a patient with multidirectional instability; note is made of an intact labrum but a capacious and redundant joint capsule anteriorly and posteriorly.

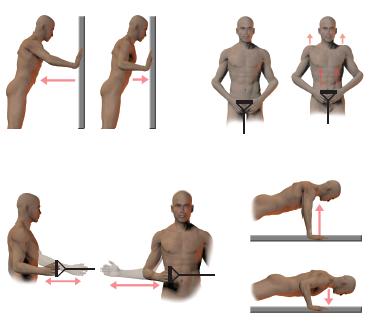

In general, rehabilitation for the unstable shoulder is based upon progressive resistive strengthening of the dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint, with emphasis on the rotator cuff and periscapular muscles (trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids, levator scapulae)28,29 (Figure 40-4).

In addition to immobilization and physical therapy, functional bracing may be a helpful adjunct in allowing young athletes to return to higher-risk activities. Buss et al.30 evaluated the results of 30 adolescent and young adult collegiate athletes who attempted to complete their sports season after a traumatic anterior instability event. Once range of motion and near-symmetric strength were achieved in the affected shoulder, these patients were allowed to participate wearing an orthosis, which prevented hyperabduction and external rotation. Twenty-six of the thirty athletes were able to complete their season, though approximately one-third of the athletes did experience recurrent instability. Interestingly, almost half of the patients in this cohort study elected to pursue surgical stabilization once their season had ended.

Arthroscopic Bankart Repair

Arthroscopic Bankart Repair

In patients with recurrent, functionally limiting or painful instability, surgical stabilization is indicated. Although historically open procedures were safely and effectively performed, arthroscopic stabilization has now become the standard of care. Indeed, comparative studies of open versus arthroscopic stabilization have demonstrated equivalent results and less morbidity with arthroscopic approaches.31–33

Arthroscopic anterior stabilization procedures are performed under general anesthesia in the lateral decubitus position. The trunk is allowed to fall back posteriorly approximately 10 degrees to align the glenoid parallel to the floor. An axillary roll is placed on the down side, and care is made to protect all bony prominences, particularly the fibular head and peroneal nerve on the contralateral down leg. Longitudinal and lateral distraction is applied using a traction boom to facilitate positioning and improve visualization; typically 7 to 10 lbs of longitudinal and 7 lbs of lateral distraction are sufficient while avoiding the complications associated with excessive traction. The limb is placed in approximately 40 degrees of abduction and 30 degrees of forward flexion.

FIGURE 40-4 Illustrations of exercises used during nonoperative treatment for shoulder instability. Emphasis is placed on strengthening deltoid, rotator cuff, serratus anterior, rhomboid, levator scapulae, and trapezius muscles, with appropriate proprioceptive retraining and biofeedback to educate the patient regarding provocative positions.

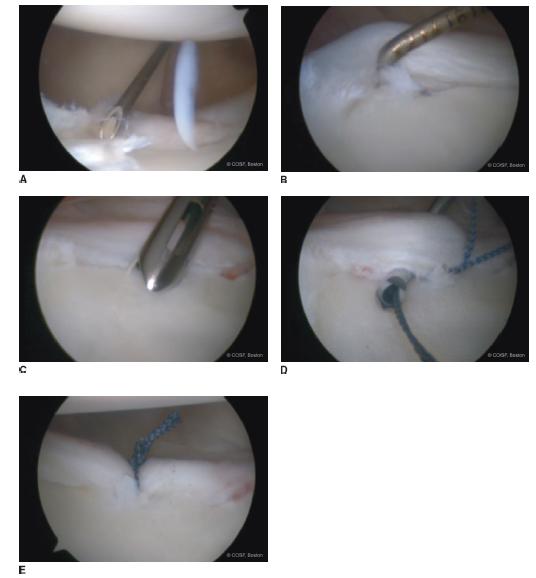

After the glenohumeral joint is insufflated with 20 mL of saline solution, the skin is incised and a 4.0-mm, 30-degree arthroscope is inserted through a standard posterosuperior portal (Figure 40-5). Arthroscopic survey is performed, and the extent of the labral tear and anterior capsular injury evaluated. Anterosuperior and anteroinferior portals are then placed through the rotator interval using an outside-in technique. In general, the anteroinferior portal is placed more laterally to provide the appropriate “angle of attack” on the glenoid during suture anchor placement. Conversely, the anterosuperior portal is placed more medially to facilitate suture passage and manipulation tangential to the glenoid face. An arthroscopic probe is utilized to confirm the initial survey findings.

Soft tissue preparation is critical to ensure biological healing, regardless of the type of implants or sutures used. In a sequential fashion using arthroscopic elevators, rasps, and shavers, fibrous tissue binding the anterior labrum and capsular tissue is removed, and a bleeding bony surface is created on the anterior glenoid neck. Adequate soft tissue mobilization can be confirmed by the “float” or “suction reduction” sign.34 With gentle suction from the posterior viewing portal, the anterior capsulolabral tissue should appear to “float” to its anatomic position on the anterior rim of the glenoid; failure to do so indicates inadequate soft tissue release and persistent medialization of the capsulolabral sleeve.

FIGURE 40-5 Arthroscopic repair of an anterior labral tear in a left shoulder. A: During establishment of the anteroinferior working portal, outside-in technique is used to start slightly lateral to the glenoid and just above the intra-articular subscapularis tendon to gain adequate access to the inferior glenoid in the appropriate trajectory to facilitate suture anchor placement. B: An arthroscopic probe is used to confirm the extent of the labral tear. C: Suture anchors are placed just onto the cartilaginous face of the glenoid. D: Arthroscopic suture passers are passed through the capsulolabral tissue lateral and inferior to the anchor site to effectuate appropriate tissue shift. E: Arthroscopic appearance after knot is tied. Note the reapproximation of the labrum to the glenoid and restoration of the “bumper” effect. A total of three anchors were used in this case.

Once the soft tissues have been adequately prepared, the repair is performed. Biocomposite suture anchors (Bio-SutureTaks, Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) are placed just on the chondral face of the glenoid, beginning in the most inferior position (typically 5:00 or 7:00). Sutures are passed through the adjacent capsulolabral tissue just medial and inferior to the anchor, thereby effectuating both an “east-to-west” and a “south-to-north” shift. Knots are tied in the standard fashion, and the process is repeated superiorly until the labral repair is complete.35 In many situations, placing the camera in the anterosuperior portal and using the posterior portal for suture shuttling will improve visualization and facilitate accurate anchor placement and suture passage, particularly in anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA) lesions.36,37 In cases where the anterior labral tear extends to the level of the biceps root, a superior labral repair is performed as well.38 At the conclusion of the procedure, a soft tissue “bumper” should be restored, and the previously noted “drive through” sign obliterated. Skin portals are closed using interrupted nylon sutures, and the limb is placed in a sling and swathe.

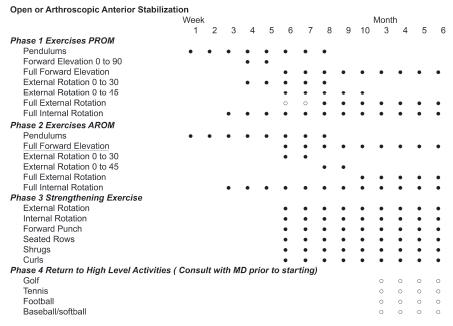

Patients remain sling immobilized for the first 4 weeks postoperatively, doing pendulum exercises only. After postoperative week 4, gentle range-of-motion exercises are initiated. An example of our current postoperative rehabilitation protocol is seen in Figure 40-6.

Posterior Instability

Posterior Instability

Pure posterior instability is much less common than anterior instability, representing 5% of shoulder instability in children and adolescents. Traditionally traumatic posterior instability was thought to be seen only in patients with a history of epilepsy or electrocution. Given the dramatic increase in high-energy sports participation in younger children, however, posterior glenohumeral joint instability is becoming more common (e.g., football, weightlifting, gymnastics, cheerleading, skateboarding). In cases where posterior instability causes pain or functional limitations refractory to physical therapy and activity modification, arthroscopic stabilization may be performed.39

While posterior stabilizations may be performed via open, anteroinferior capsular shift or posterior capsulorrhaphy procedures, arthroscopic stabilization may provide the best visualization and access for appropriate soft tissue reconstruction. Patients are placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected limb suspended in overhead longitudinal and lateral distraction. While similar to positioning for anterior arthroscopic labral repairs, judicious adjustment of shoulder position (e.g., more lateral distraction, less forward flexion) may improve visualization of the posterior joint space. After arthroscopic survey and establishment of anterosuperior and anteroinferior portals within the rotator interval, the camera is moved to the anterosuperior portal. Soft tissue preparation is performed in the standard fashion. Capsulolabral tissue is mobilized and the bony glenoid prepared as in anterior Bankart repairs. In cases where the labrum is intact and a capsulorrhaphy is to be performed, the capsule is “roughened” using arthroscopic rasps or shavers run in reverse without suction to stimulate punctate bleeding and a healing response. Suture anchors are placed sequentially from inferior to superior, and sutures are shuttled in the standard fashion through the capsulolabral tissues to effectuate an inferior-to-superior and medial-to-lateral shift of tissue. (In cases of posterior capsulorrhaphy without labral repair, plication “pinch-tuck” sutures are placed from inferior to superior and “parked” in the anteroinferior working portal.) After all sutures are placed, they are tied sequentially from inferior to superior, completing the soft tissue repair.

FIGURE 40-6 Example of a rehabilitative protocol following arthroscopic anterior shoulder stabilization.

Two technical points are worth noting. First, we do not typically utilize a posteroinferior 7:00 portal; adequate access to the posteroinferior glenoid and capsule can be achieved via the posterosuperior and anteroinferior portals without conferring additional risk to the axillary nerve. Second, sutures are passed but not tied until all planned anchors/sutures have been placed. This prevents the frequent difficulties in both visualization and intra-articular maneuvering that occur if the posterior capsule is closed prior to the placement of all sutures.

Postoperatively patients are placed in sling immobilization, and the rehabilitation protocol is similar to anterior instability reconstruction.

Latarjet Procedure

Latarjet Procedure

If you are going to be a successful duck hunter, you must go where the ducks are.

—Paul “Bear” Bryant

While arthroscopy is a powerful tool, open surgical reconstruction remains the standard for shoulder instability associated with significant glenoid deficiency. The answer to the question, “How much bone loss is too much?” however, continues to be investigated. Lo et al.40 initially proposed that loss of 25% to 27% of the glenoid width constituted a glenoid defect worthy of bony augmentation. Itoi et al.41 proposed that an osseous defect in which the width was 21% of the glenoid length was of sufficient magnitude to result in persistent instability after Bankart repair alone. Gerber and Nyffeler42 had similar conclusions, demonstrating that loss of more than half of the glenoid width resulted in marked decrease in resistance to dislocation. Finally, Yamamoto et al.43 demonstrated in a cadaveric model that an anterior defect of 20% of the glenoid length (6 mm) resulted in dramatically decreased joint stability.

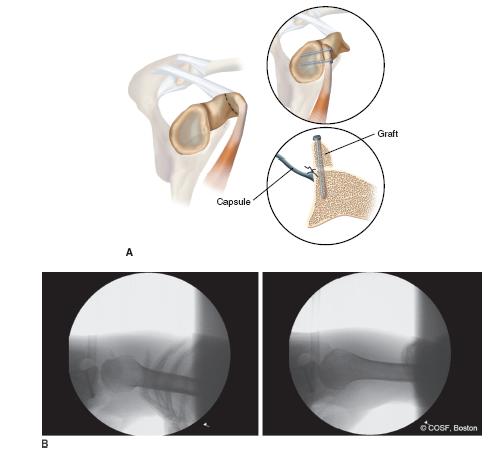

In cases of critical glenoid deficiency, bony augmentation procedures are indicated. While there have been a plethora of techniques proposed, the Latarjet procedure remains our current operation of choice.44,45 This procedure utilizes the coracoid process with attached conjoined tendon as a bone graft affixed to the anterior-inferior glenoid. Stability is imparted by the increased articular arc of the glenoid as well as the “sling effect” of the conjoined tendon across the anterior-inferior glenohumeral joint (Figure 40-7).

Patients are placed in the modified beach chair position; an arm holder or positioner is used if available. Initial arthroscopic evaluation is performed to assess for associated pathology and to confirm the severity of bone loss. While various measures have been utilized, perhaps the easiest and most reliable is measuring the distance from the “bare spot” of the glenoid to the anterior glenoid rim. If this distance is <4 to 6 mm, consideration should be made for Latarjet reconstruction. (Alternatively, the percentage of bone loss may be estimated as 1 – (distance from bare spot to posterior rim + distance from bare spot to anterior rim/2 × distance from bare spot to posterior rim) (Figure 40-8).

After arthroscopic confirmation, an open Latarjet procedure is performed. The shoulder is approached via an anterior incision, based medially over the coracoid process. After the deltopectoral interval is developed and cephalic vein taken laterally, the coracoid process is identified. A spiked Hohmann or Cobra retractor is placed superiorly over the coracoid in the region of the coracoclavicular ligaments. With abduction and external rotation of the shoulder, the coracoacromial ligament is divided, leaving a 1-cm cuff of tissue attached to the bone for later use. The shoulder is then adducted and internally rotated, and the pectoralis minor insertion is released off the coracoid. Repeat abduction and external rotation will then allow for easy division of the coracohumeral ligament. Blunt dissection with the assistance of a peanut is then performed to free up adjacent adhesions. The entire coracoid must be easily visualized, often more proximally than initially believed.

A 90-degree-angled saw is then used to osteotomize the coracoid from lateral to medial, just distal to the coracoclavicular ligament insertions. The length of coracoid bone should be approximately 3 cm. Once the bony cut is completed, the osteotomy fragment is mobilized, preserving the conjoined tendon attachment and protecting the musculocutaneous nerve, which enters the coracobrachialis approximately 4 to 5 cm distal to the coracoid tip. With a hemostat or Kocher clamp placed and the coracoid reflected inferiorly, the deep surface is exposed and may be decorticated and flattened with the microsagittal saw. Two drill holes are created from the deep to superficial surface for subsequent screw fixation; electrocautery or marking pen is used to mark the exit holes on the superficial surface.

FIGURE 40-7 The modified Latarjet procedure. A: Schematic diagram depicting use of the coracoid process and attached conjoined tendon to augment the anterior glenoid. B: Intraoperative fluoroscopic images following Latarjet procedure. Note is made of appropriate screw fixation and precise placement of the coracoid bone block.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree