2Pathology Department, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Overview

- Breast conditions account for approximately 25% of all surgical referrals

- Guidelines for referral exist to ensure that patients with breast cancer do not suffer delays in referral

- Cancer can present as localised nodularity, particularly in young women

- All discrete masses and the majority of localised asymmetric nodularities require triple assessment

- Delay in diagnosis of breast cancer is the single largest cause for medicolegal complaints

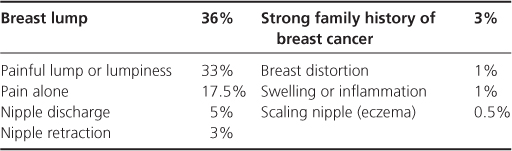

One woman in four is referred to a breast clinic at some time in her life. A breast lump, which may be painful, and breast pain constitute over 80% of the breast problems referred to hospital and breast problems constitute up to a quarter of all female surgical referrals (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Prevalence of presenting symptoms in patients attending a breast clinic.

When a patient presents with a breast problem the question for the general practitioner is: ‘Is there a chance that cancer is present and, if not, can I manage these symptoms myself?’ (Figure 1.1; Tables 1.2 and 1.3).

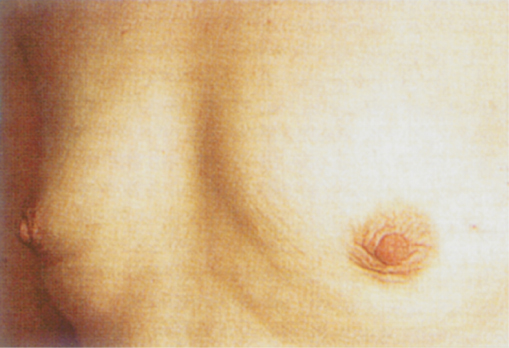

Figure 1.1 Bathsheba by Rembrandt. Much discussion surrounds the shadowing and possible distortion of the left breast and whether this represents an underlying malignancy. Such findings would be an indication for hospital referral.

Table 1.2 Conditions that require hospital referral.

| Lump |

|

| Pain |

|

| Nipple discharge |

|

| Nipple retraction or distortion |

| Nipple eczema |

| Change in skin contour |

| Family history |

| Request for assessment of a woman with a strong family history of breast cancer should be to a family cancer genetics clinic. |

Table 1.3 Patients who can be managed, at least initially, by their GP.

|

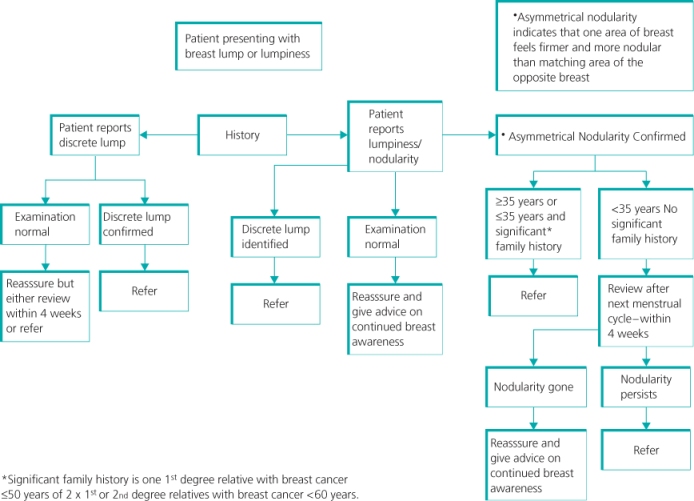

For patients presenting with a breast lump, the general practitioner should determine whether the lump is discrete or there is nodularity, as well as whether any nodularity is asymmetrical or is part of generalised nodularity (Figure 1.2). A discrete lump stands out from the adjoining breast tissue, has definable borders and is measurable. Localised nodularity is more ill defined, is often bilateral and tends to fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. About 10% of all breast cancers present as asymmetrical nodularity rather than a discrete mass. When the patient is sure that there is a localised lump or lumpiness, a single normal clinical examination by a general practitioner is not enough to exclude underlying disease (Tables 1.2 and 1.3). Reassessment after menstruation or hospital referral is indicated in such women.

Figure 1.2 Management of patient presenting in primary care with a breast lump or localised lumpy area or nodularity.

Assessment of Symptoms

Patient’s History

Details of risk factors, including family history and current medication, should be obtained and recorded. Knowing the duration of a symptom can be helpful, as cancers usually grow slowly but cysts may appear overnight.

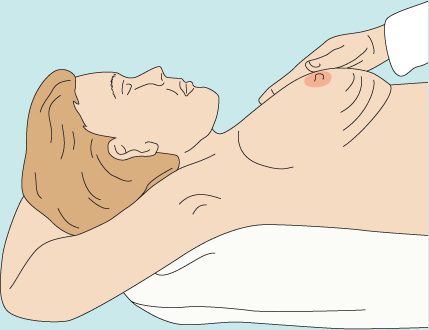

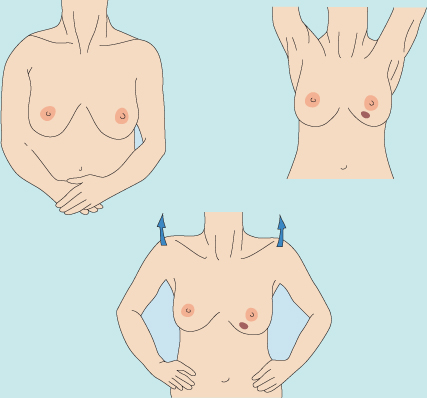

Inspection should take place in a good light with the patient’s arms by her side, above her head, then pressing on her hips (Figure 1.3). Skin dimpling or a change in contour is present in up to a quarter of symptomatic patients with breast cancer (Figure 1.4). Although usually associated with an underlying malignancy, skin dimpling can follow surgery or trauma, and can be associated with benign conditions or occur as part of breast involution (Figures 1.5–1.7).

Figure 1.3 Position for breast inspection. Skin dimpling in lower part of breast evident only when arms are elevated or pectoral muscles contracted.

Figure 1.4 Skin dimpling (left) and change in breast contour (right) associated with underlying breast carcinoma.

Breast Palpation

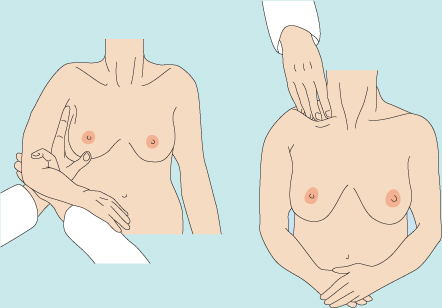

Breast palpation is performed with the patient lying flat with her arms above her head (Figure 1.8), and all the breast tissue is examined using the most sensitive part of the hand, the fingertips. It is important for the woman to have her hands under her head to spread the breast out over the chest wall, because it reduces the depth of breast tissue between your hands and the chest wall and makes abnormal areas much easier to detect and define. If an abnormality is identified, it should then be assessed for contour and texture. The presence of deep fixation is checked by tensing the pectoralis major, which is accomplished by asking the patient to press her hands on her hips. All palpable lesions should be measured with calipers. A clear diagram of any breast abnormalities, including dimensions and the exact position, should be recorded in the medical notes.

Patients with breast pain should also be examined, the underlying chest wall being palpated for areas of tenderness while the woman lies on each side (see Chapter 3). Much so-called breast pain in fact emanates from the underlying chest wall.

Assessment of Axillary Nodes

Once both breasts have been palpated, the nodal areas in the axillary and supraclavicular regions are checked (Figure 1.9). Clinical assessment of axillary nodes can be inaccurate: palpable nodes can be identified in up to 30% of patients with no clinically significant breast or other disease, and up to a third of patients with breast cancer who have clinically normal axillary nodes have axillary nodal metastases.

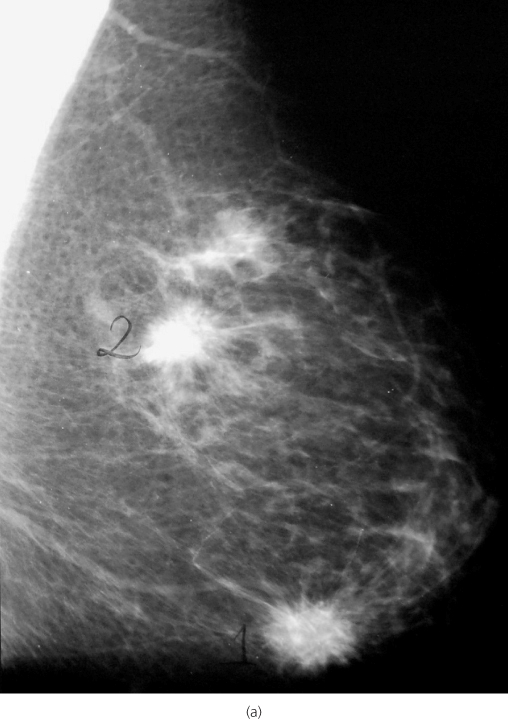

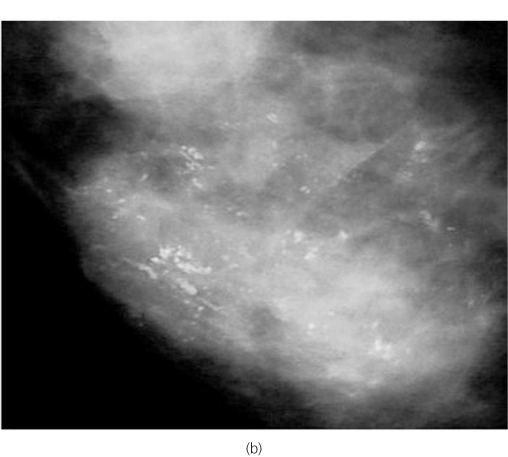

Mammography

Mammography requires compression of the breast between two plates and is uncomfortable. Two views—oblique and craniocaudal—are usually obtained. With modern equipment a dose of less than 1.5 mGy is standard. Mammography allows detection of mass lesions (Figure 1.10), areas of parenchymal distortion and microcalcifications. Breasts are relatively radiodense, so in younger women aged under 35 mammography is of more limited value and should not be performed unless on clinical examination, cytology or core biopsy there is a suspicion that the patient has a cancer (Figure 1.10). Digital mammography, which is now being used in most units, has a greater sensitivity for cancer detection in young women than standard film mammography. All patients with breast cancer, regardless of age, should have mammography before surgery to help with assessment of the extent of disease.

Figure 1.10 (a) Oblique mammogram showing two spiculated mass lesions characteristic of breast cancers in left breast. (b) Malignant calcification characteristic of high-grade DCIS.

Ultrasonography

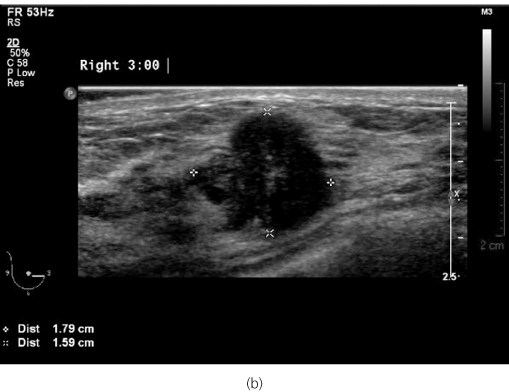

In ultrasonography high-frequency sound waves are beamed through the breast and reflections are detected and turned into images. Cysts show up as transparent objects; other benign lesions tend to have well-demarcated edges (Figure 1.11(a)), whereas cancers usually have indistinct outlines (Figure 1.11(b)). Blood flow to lesions can be imaged with colour flow Doppler ultrasound. Malignant lesions tend to have a greater blood flow than benign lesions, but the sensitivity and specificity of colour Doppler are insufficient to differentiate benign from malignant lesions accurately. All patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer should have both a whole breast and an axillary ultrasound. If other evidence of disease is identified or abnormal nodes are seen, they should be biopsied under ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound contrast agents are available and continue to be investigated, but they are of no proven value in the routine assessment of breast masses or axillary nodes.

Figure 1.11 (a) Ultrasound showing a solid irregular mass lesion characteristic of a cancer. (b) Ultrasound of a fibroadenoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree