2Western General Hospital, Pathology Department, Edinburgh, UK

Overview

- Carcinoma in situ is diagnosed when malignant cells remain within the basement membrane of the elements of the terminal duct lobular unit; invasive cancers invade outside the basement membrane of the ducts and lobules

- Invasive cancers can be split into different types and different grades and these have prognostic implications

- Tumours are classified based on a variety of receptors, including oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 receptor

- Local surgery consists of breast-conserving surgery (wide local excision) or mastectomy

- Radiotherapy is given after breast-conserving surgery and to selected patients after mastectomy

Breast cancers are derived from epithelial cells that are found in the terminal duct lobular unit. Cancer cells that remain within the basement membrane of the elements of the terminal duct lobular unit and the draining duct are classified as in situ or non-invasive. An invasive breast cancer is one in which there is dissemination of cancer cells outside the basement membrane of the ducts and lobules into the surrounding adjacent normal tissue. Both in situ and invasive cancers have characteristic patterns by which they can be classified.

Classification: Invasive Breast Cancer

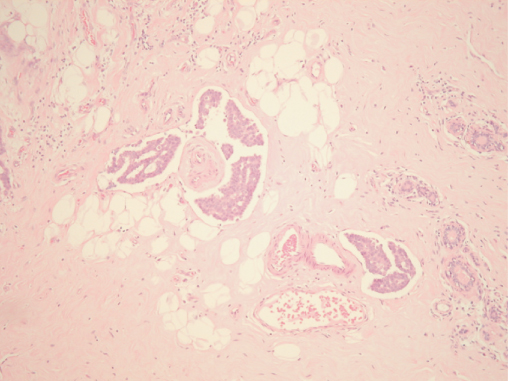

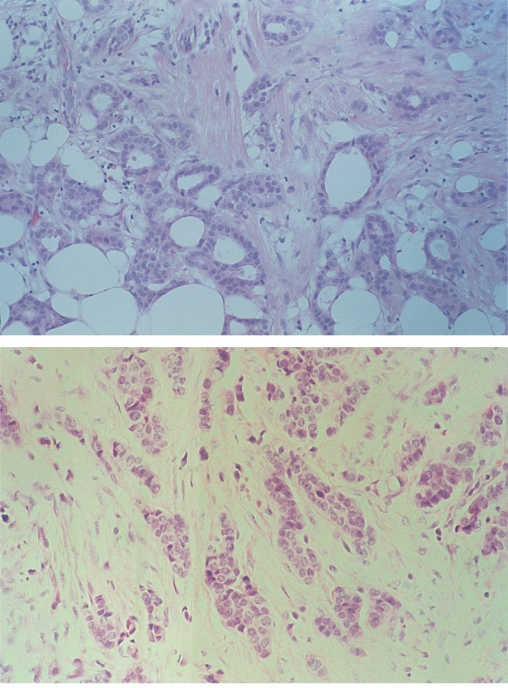

The most commonly used classification of invasive breast cancers divides them into ductal and lobular types. This was based on the belief that ductal carcinomas arose from ducts and lobular carcinomas from lobules. As all invasive ductal and lobular breast cancers arise from the terminal duct lobular unit, this terminology is confusing, although it is still used. Some tumours show distinct patterns of growth and cellular morphology, and so certain types of breast cancer can be identified (Figure 8.1). Those with specific features are called invasive carcinomas of special type, the others are considered to be of no special type (Table 8.1). This classification has clinical relevance in that certain special-type tumours have a better prognosis or different clinical characteristics and clinical behaviour compared with tumours of no special type.

Figure 8.1 Invasive tubular carcinoma of the breast; in the left centre there is also an area of DCIS (on the lower left).

Table 8.1 Classification of invasive breast cancers.

| Special types | No special type |

|

|

Tumour Differentiation

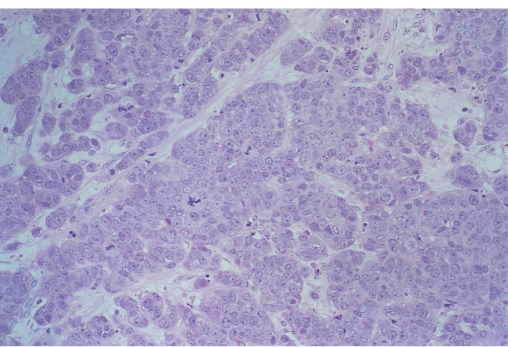

Among the cancers of no special type, grading the degree of differentiation of the tumour can yield prognostic information (Figure 8.2). Degrees of glandular formation, nuclear pleomorphism and frequency of mitoses are scored from 1 to 3. These values are combined and converted into three groups: grade I (score 3–5), grade II (scores 6 and 7) and grade III (scores 8 and 9).

Figure 8.2 Invasive carcinomas showing diffuse infiltration through breast tissue: grade I (top); grade II (middle); grade III (bottom).

Tumour grade is an important predictor of both disease-free and overall survival. The introduction of molecular diagnostics has heralded a change in the way breast cancers are now reported. Markers such as hormone receptors and the growth factor receptor HER2 neu are reported routinely.

Oestrogen Receptor

Approximately three-quarters of breast cancers express significant amounts of oestrogen receptor (ER). This can be assessed immunohistochemically and scored using an Allred score that ranges from 0–8 (there is no 1), a histoscore that multiplies the percentage of cells staining positively by the intensity of the stain (1 weak, 2 moderate, 3 strong) to produce a score of 0–300 or can just be reported as the percentage of positively staining cells in the range of 0–100. An estimate of the RNA messenger for ER is included as one component of the recurrence score (Chapter 17). Cancers that express ER tend to be ER rich and most ER-positive cancers have an Allred score of 7 or 8, with few scores falling between 2 and 6.

Progesterone Receptor

The majority of ER-positive cancers express progesterone receptors (PgR). Cancers which are both ER- and PR-positive have the greatest probability of responding to hormone therapy. There are very few PgR-positive ER-negative cancers. Scoring for PgR is as for ER.

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors

There are four human epidermal growth factor receptors (HER). These are HER1, also known as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); HER2, also known as cerb2 (it is called this because it causes erythromblastosis in chickens); and the other two, which are lesser known, HER3 and HER4. Currently HER2 is the only epidermal growth factor receptor assessed routinely. Initial screening is usually with an antibody with staining being classified as 0, + (both are considered HER negative), + + (considered equivocal) and +++ (considered positive). All ++ cases are assessed by fluorescence in situ hydridisation (FISH) and the ratio of copies of HER2 to copies of the chromosome 17 (the chromosome where HER2 is situated on the long arm). A score of ≥2.0 is considered positive. Methods that use other markers other than fluorescence are also available and are used in some laboratories as their only test.

Approximately 15–20% of all cancers are HER2 positive. Most ER-positive cancers (90% + ) are HER2 negative. Cancers that are ER negative, PgR negative and HER2 negative are called triple-negative cancers. These are more common in BRCA1 carriers. Approximately half of triple-negative cancers respond well to chemotherapy, but some triple-negative cancers are chemotherapy resistant. Originally HER2-positive and triple-negative cancers had a poorer outlook than HER2-negative ER-positive cancers. With the advent of specific anti-HER2 therapies the survival of HER2 positive cancers patients has increased dramatically over recent years.

Other Features

Several other histological features in the primary tumour are valuable in predicting local recurrence and prognosis.

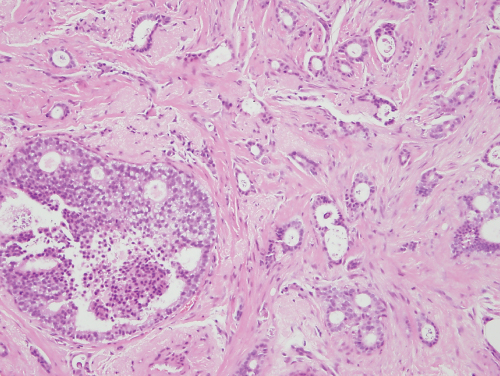

Lymphatic or Vascular Invasion (LVI)

The presence of cancer cells in blood or lymphatic vessels (Figure 8.3) is a marker of more aggressive disease, and patients with this feature are at increased risk of both local and systemic recurrence.

Extensive in situ Component

Patients with 25% of the main tumour mass consisting of non-invasive disease with in situ cancer in the surrounding breast tissue have been classified as having an extensive in situ component (EIC) and were formerly considered to be at increased risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving treatment. It is now appreciated that if an invasive cancer with EIC is excised to clear margins then the risk of recurrence is not greater than for cancers without EIC.

Investigation

All patients with invasive breast cancers should have 2 view mammography with or without magnification mammography and whole breast ultrasound. Any evidence of multifocality or multicentricity or of suspected extensive in situ disease that might influence surgical treatment should be confirmed by image-guided core biopsy. Patients with invasive cancer should also have axillary ultrasound with FNA or core biopsy of any suspicious axillary nodes. Ultrasound with subsequent FNA or core can detect up to 60% of patients with involved axillary nodes.

MRI may be valuable in selected patients, but has not been shown to be of value when performed routinely in women who are suitable for breast-conserving surgery. The COMICE randomised trial of MRI in patients suitable for breast-conserving surgery showed that MRI did not increase the rate of complete excision or in the short term reduce the number of local recurrences after breast-conserving therapy.

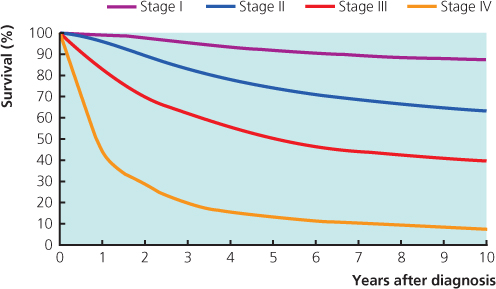

Staging of Invasive Breast Cancers

The extent of invasive disease should be assessed and the tumour staged. The current staging classifications are not well suited to breast cancer: the tumour node metastases (TNM) system (Table 8.2) depends on clinical measurements and clinical assessment of lymph node status, both of which are inaccurate, and the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) system (Table 8.3) incorporates the TNM classification (Figures 8.2 and 8.3). To improve the TNM system, a separate pathological classification has been added to include tumour size and node status, as assessed by a pathologist. Prognosis in breast cancer relates to the stage of the disease at presentation.

Table 8.2 TNM classification of breast tumours.

| Tis Cancer in situ | T4d Inflammatory cancer |

| T1 ≤2 cm (T1a ≤0.5 cm, T1b >0.5–1, T1c >1–2 cm) | N0 No regional node metastases |

| T2 >2–5 cm | N1 Palpable mobile involved ipsilateral axillary nodes |

| T3 >5 cm | N2 Fixed involved ipsilateral axillary nodes |

| T4a Involvement of chest wall | N3 Ipsilateral internal mammary node involvement (rarely clinically detectable) |

| T4b Involvement of skin (includes ulceration, direct infiltration, peau d’orange and satellite nodules) | M0 No evidence of metastasis |

| T4c, T4a and T4b together | M1 Distant metastasis (includes ipsilateral supraclavicular nodes) |

Table 8.3 Correlation of UICC (1987) and TNM classification of tumours.

| UICC stage | TNM classification |

| I | T1, N0, M0 |

| II | T1, N1, M0; T2, N0–1, M0 |

| III | Any T, N2–3, M0; T3, any N, M0; T4, any N, M0 |

| IV | Any T, any N, M1 |

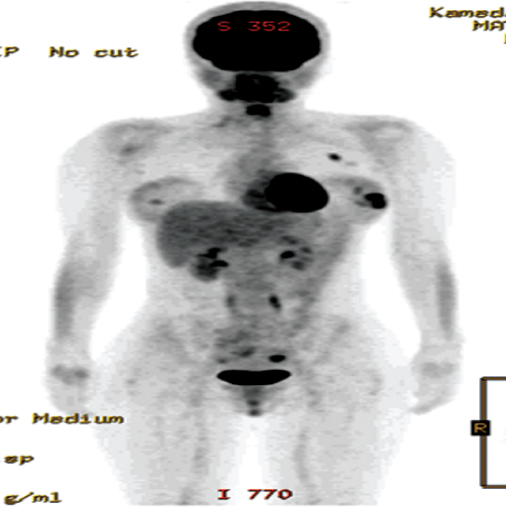

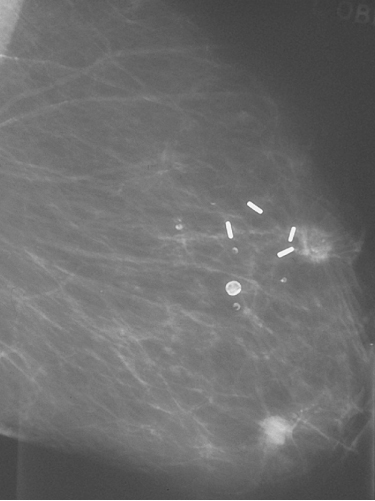

Patients with stage I and stage II disease have a low incidence of detectable spread, and in the absence of specific signs or symptoms they should not undergo further investigations to identify metastatic disease (Figure 8.4). Patients with larger or more advanced tumours should be considered for CT or CTPET scans (Figure 8.5).

Surgical Treatment of Localised Breast Cancer

Most patients will have a combination of local treatments to control local disease and systemic treatment to combat any micrometastatic disease. Local treatments consist of surgery and radiotherapy. Surgery can be excision of the tumour with surrounding normal breast tissue (breast-conservation surgery) or mastectomy. At least 12 randomised clinical trials have compared mastectomy and breast-conservation treatment and shown a non-significant 2% (SD 7%) relative reduction in death in favour of breast-conserving therapy. Local recurrence rates were similar, with a non-significant 4% (SD 8%) relative reduction in favour of mastectomy (Figure 8.6). Two large randomised trials comparing mastectomy and breast-conserving therapy have shown no significant differences in survival after 20 years of follow-up.

Figure 8.6 Patient who was treated with breast conservation and developed a new primary cancer in the lower part of the treated breast. The metal clips mark the site of the original cancer. Up to half of so called recurrences after breast conservation are second primary cancers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree