Overview

- Breast infection during breastfeeding is less common than it used to be

- Early prescription of appropriate antibiotics in infection limits abscess formation

- Delay in referral to breast clinics of patients with lactating infection that does not settle rapidly with antibiotics continues to be a problem

- Breast abscesses can be aspirated or drained through a very small skin incision

- Breast cancer should be excluded in patients with inflammatory changes that do not settle rapidly on appropriate therapy

Breast infection is now much less common than it used to be. It is seen occasionally in neonates, but it most commonly affects women aged between 18 and 50; in this age group it can be divided into lactational and non-lactational infection. Infection can affect the skin overlying the breast, when it can be a primary event, or it may develop secondary either to a lesion in the skin, such as a sebaceous cyst, or to an underlying skin condition, such as hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment

There are four guiding principles in treating breast infection:

- Appropriate antibiotics should be given early to reduce the likelihood of abscess development (Tables 4.1 and 4.2).

- Hospital referral is indicated if the infection does not settle rapidly following one course of antibiotic treatment.

- If an abscess is suspected it should be confirmed by ultrasonography, aspiration or both before surgical drainage is considered.

- Breast cancer should be excluded in patients with an inflammatory lesion that is solid on ultrasonography or on aspiration that does not settle despite apparently adequate antibiotic treatment.

Table 4.1 Organisms responsible for breast infection.

| Type of breast infection | Organism |

| Neonatal | Staphylococcus aureus (rarely Escherichia coli) |

| Lactating and hidradenitis suppurativa | S aureus (rarely S epidermidis and streptococci) |

| Non-lactating | S aureus, enterococci, anaerobic streptococci, Bacteroides spp |

| Skin associated | S aureus |

Table 4.2 Antibiotics most appropriate for treating breast infections.

| Type of breast infection | No allergy to penicillin | Allergy to penicillin |

| Neonatal, lactating and skin associated** | *Flucloxacillin (500 mg four times daily) | *Erythromycin (500 mg twice daily) |

| Non-lactating | *Co-amoxiclav (375 mg three times daily) | Combination of *erythromycin (500 mg twice daily) with metronidazole (200 mg three times daily) |

*Adult doses.

**Beware of MRSA in lactating infection. Follow advice of local microbiologist for appropriate antibiotic therapy.

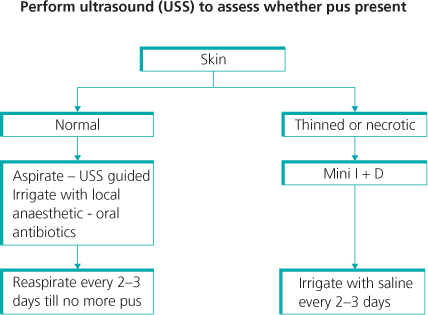

All abscesses in the breast can be managed by repeated aspiration or incision and drainage (Figure 4.1).

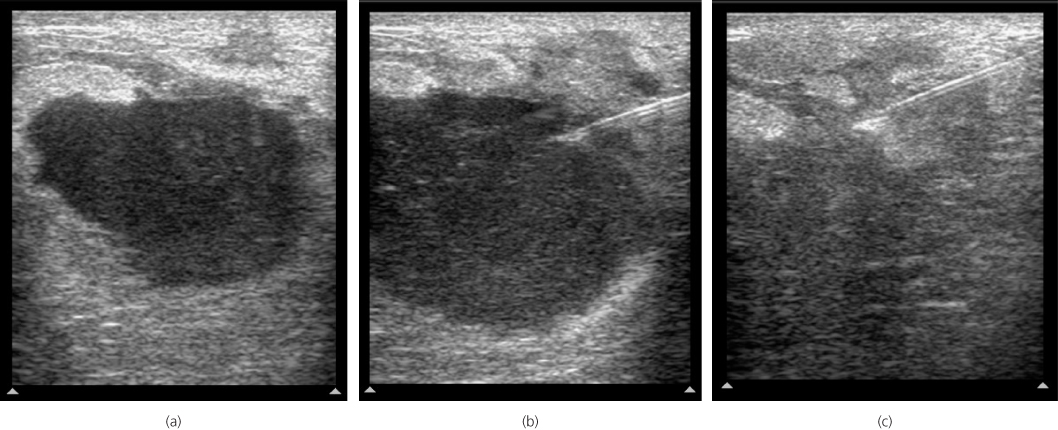

Aspiration is best performed with ultrasound guidance (Figure 4.2), with the abscess cavity being lavaged with local anaesthetic to dilute out and to help aspirate pus and reduce pain. Repeated aspiration every 2–3 days is required to achieve resolution of larger breast abscesses. For the largest abscesses aspiration may need to be repeated five or more times.

Figure 4.2 (a) Ultrasound of lactating breast abscess. (b) Lactating breast abscess—needle in abscess. (c) Following aspiration.

Incision and drainage, if indicated, can almost always be performed under local anaesthesia except in children; placement of a drain or packing the abscess cavity after incision and drainage is unnecessary. Prior to incision and drainage, 1% lignocaine containing 1 in 200 000 adrenaline is injected into the skin overlying the abscess. Only a small incision is required to drain a breast abscess adequately. After incision the abscess is irrigated with the same local anaesthetic solution to wash out residual pus and to limit the pain of the procedure.

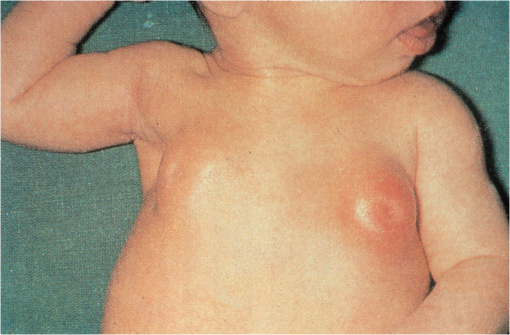

Neonatal Infection

Neonatal breast infection is not common, but can occur in the first few weeks of life when the breast bud is enlarged (Figure 4.3). Although Staphylococcus aureus is the usual organism, occasionally infection is due to Escherichia coli. If an abscess develops, a small incision placed as peripherally as possible to avoid damaging the breast bud leads to rapid resolution.

Lactating Infection

Better maternal and infant hygiene and early treatment with antibiotics have considerably reduced the incidence of abscess formation during lactation. Infection is more frequent following a first child and most commonly seen within the first six weeks of breastfeeding, although some women develop it during weaning. Lactating infection presents with pain, swelling and tenderness. There is usually a history of a cracked nipple or skin abrasion, but this is not the site of entry of organisms. S aureus is the most common organism responsible, but S epidermidis and streptococci are occasionally isolated. Drainage of milk from the affected area is reduced. Promotion of milk drainage and early antibiotic therapy are the cornerstones of treatment. Tetracycline, ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol should not be used to treat lactating breast infection as they may enter breast milk and can harm the baby. The pain of lactation mastitis is helped by the application of gel packs or cold cabbage leaves to the breast; both are equally efficacious. In one very small randomised study, although more women preferred cabbage leaves, gel packs produced somewhat greater pain relief.

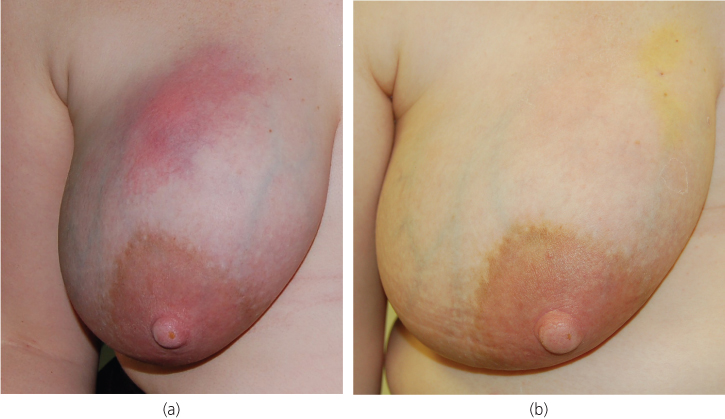

If infection does not settle after one course of antibiotics, no pus is detected on ultrasonography, and if clinical and imaging assessments indicate that the lesion is infective or inflammatory, the antibiotic should be changed to cover other possible pathogens, including MRSA. If inflammation or an associated mass lesion persists, further investigation is required to exclude an underlying inflammatory carcinoma (Figure 4.4).

The management of breast abscesses (Figure 4.1) includes an initial ultrasound to determine whether an abscess with visible pus is present (Figure 4.2). An established abscess should be treated by either repeated aspiration—every 2–3 days until no more pus is aspirated (Figure 4.5)—or incision and drainage (Figures 4.6 and 4.7). Women who want to continue breastfeeding should be encouraged to do so. Breastfeeding is often less painful than using a breast pump and is more effective at encouraging milk flow. There are some women who present with multiple areas of breast infection who are exhausted by breastfeeding (Figure 4.8) in whom consideration should be given to stopping breastfeeding and halting milk flow. Stopping milk production is achieved by prescribing cabergoline 2.5 mcg given twice a day for two days.

Figure 4.5 (a) Lactating abscess, skin red but normal at presentation. (b) Lactating abscess following aspiration.

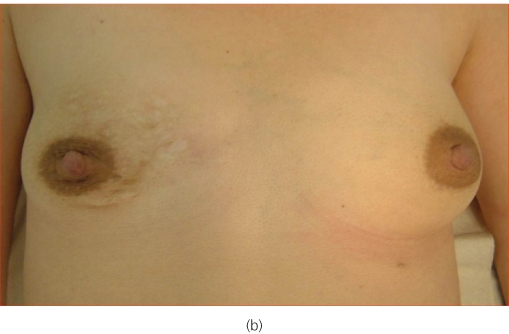

Figure 4.6 A breast abcess that developed during breastfeeding. Before treatment (a) and after mini-incision and drainge (b).

Delay in hospital referral of breast feeding infection continues to be an issue (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9 (a) Infection and abscess in right breast where hospital referral was delayed. (b) After resolution of infection showing asymmetry as a consequence of tissue loss from delayed referral.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree