The tibial tubercle is the site of an apophysis, a chondro-osseous prominence or protuberance that experiences repetitive traction forces from a tendinous attachment. Prior to skeletal maturity, these tensile forces make the cartilaginous plate of the apophysis structurally different than the adjacent proximal tibial physis, which is subjected to compressive forces. The tibial tubercle apophysis has a large fibrocartilaginous component, helping it to withstand the strong tensile forces produced by the patellar tendon.3

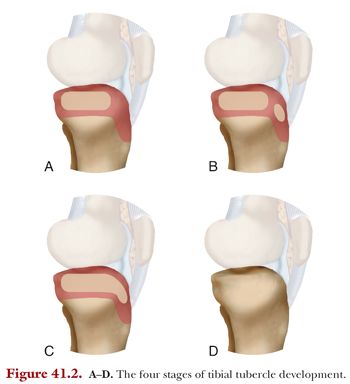

The tibial tubercle has been described as developing through four stages during childhood and adolescence (Fig. 41.2).4 The four stages have been named the cartilaginous stage, the apophyseal stage, the epiphyseal stage, and the bony stage. In the cartilaginous stage, the tubercle is entirely made of cartilage and not evident on x-ray. In the apophyseal stage, the secondary ossification center of the tubercle appears as a discrete entity. In the epiphyseal stage, the tubercle ossification center unites with the proximal tibia ossification center, but cartilage remains, deep to this bony portion of the apophysis. In the bony stage, the physis and apophysis ossify completely, or “close.”3

Multiple theories on the etiology of OSD have been proposed. These include mechanical avulsion, patellar tendon degeneration, avascular necrosis, and infection. However, the majority of research supports the mechanical theory that OSD is caused by repetitive traction-based microtrauma to the cartilaginous portion of the apophysis. There may also be one or more discreet episodes of new or increased tibial tubercle pain during the late cartilaginous or apophyseal stage, which can serve as inciting events for the more chronic, inflammatory condition.3,5–8 However, OSD should be differentiated from a true tibial tubercle fracture, which generally requires a higher energy traumatic event and is distinct from the overuse phenomenon. In OSD, the aforementioned adaptive changes of the apophysis lead to the tubercle being vulnerable to traction forces. A tiny fragment or fragments of chondral tissue can be pulled proximally, away from the rest of the tubercle, and may generate small ossicles or fragments of bone. Discrete ossicles can form that are not confluent with the rest of the tibial tubercle9 and may lead to pain, tenderness, local edema, and inflammation of the distal patellar tendon (patellar tendonitis).5,9

OSD is a remarkably common cause of knee pain in adolescents of both sexes, with a higher incidence in boys than girls.10 One study suggested that OSD affects 13% of adolescents.11 However, it is almost twice as common (21%) in adolescents who are involved in sports and less than half as common (5%) in adolescents not involved in sports.11 The apophyseal stage of tibial tubercle development, which occurs roughly between the ages of 10 and 15 years, is the stage during which OSD most commonly arises. Studies have demonstrated the average age of symptom onset to be 12 to 15 years old.11–13 A third to a half of afflicted adolescents have bilateral knee involvement.10,11,14 When unilateral, OSD usually affects the knee of the jumping or “take-off” leg.11

History and Physical Examination

The diagnosis of OSD is typically made based on history and physical examination findings rather than imaging findings. Patients will often complain of knee pain localized to the “front” of the knee or a “bump just below the knee.” The duration of symptoms can vary from weeks to years. The pain experienced and degree of limitation can range from a mild, dull, achy discomfort to a severe limp, sometimes even requiring crutches.

Physical examination is critical for distinguishing OSD from other similar knee disorders that can affect adolescents or preadolescents. Tenderness in OSD is at the distal patellar tendon and tibial tubercle. A prominent tibial tubercle may be visible and tender free ossicles may be palpable.

The differential diagnosis of knee disorders similar to OSD includes two other overuse injuries of the knee extensor mechanism, namely patellar tendonitis and Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome. However, these entities are generally distinguishable from OSD on physical exam because the pain and tenderness are at the proximal patellar tendon and distal pole of the patella rather than at the distal patellar tendon and tibial tubercle. Although rare, it is possible to have a combination of these overuse injuries at the same time.

Imaging

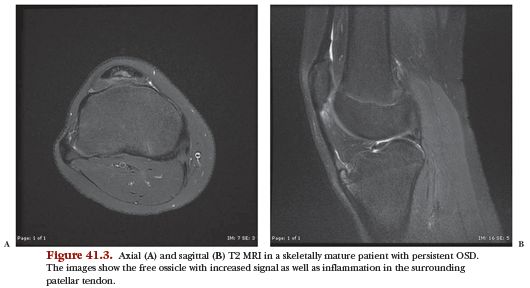

Radiographic findings in patients with active OSD will most commonly be absent, with no difference from normal knee x-rays in asymptomatic children. However, radiographs can, in some cases, support the diagnosis if one or more ossicles are seen on the lateral view. Moreover, x-rays are important for ruling out other pathology if knee symptoms are grossly asymmetrical or are not limited to the region of the tubercle. Radiographs are recommended if surgery is being considered for a skeletally mature patient complaining of tibial tubercle pain. Standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views are generally sufficient when radiographs are obtained, although one study has suggested that a lateral view with 10 to 20 degrees of internal rotation allows for better visualization of the profile of the tibial tubercle.10 Further imaging modalities, such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have been shown to be effective at diagnosing OSD but are rarely needed (Fig. 41.3).9,15,16