Surgical Cricothyrotomy

Gary R. Strange

Leo G. Niederman

Introduction

The majority of children who require airway control or assisted ventilation can be managed with standard means such as bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation or tracheal intubation. However, occasionally these techniques fail or cannot be performed. In these cases, alternative means of airway control must be employed. Three common alternatives to standard airway techniques are surgical cricothyrotomy, percutaneous needle cricothyroidotomy with transtracheal ventilation, and retrograde intubation. This chapter discusses the technique of surgical cricothyrotomy; the other two techniques are discussed in Chapters 17 and 18.

Surgical cricothyrotomy involves dissection of the anterior neck and visualized incision of the cricothyroid membrane or, alternatively, wire-guided insertion of a special catheter or tracheal tube. The technique has been well described in the adult population, but experience in young children is anecdotal or limited. Furthermore, surgical cricothyrotomy has received little description in standard pediatric emergency medicine texts, and ideal training for this procedure in children has not been developed or evaluated.

Anatomy and Physiology

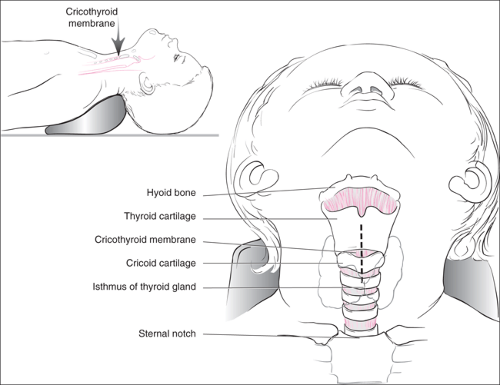

Important to understanding any invasive airway procedure is knowledge of the anatomy of the anterior neck, larynx, and trachea (Fig. 26.1). The larynx, which consists of the thyroid cartilage, the cricothyroid membrane, and the cricoid cartilage, lies in the anterior neck, deep to the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and sternohyoid muscle. The thyroid cartilage is cephalad to the cricothyroid membrane, and the cricoid cartilage is caudad to it. The fibroelastic cricothyroid membrane can be palpated as an indentation between the two more prominent cartilage structures.

The cricoid cartilage attaches inferiorly to the tracheal rings. At approximately the same level of the junction of the cricoid membrane and the trachea is the isthmus of the thyroid gland. Care must be taken during dissection to avoid this structure. Additionally, although the cricothyroid membrane is relatively avascular, the superior thyroid artery crosses the superior portion of the membrane and can be damaged during dissection or incision.

In adolescents and adults, the cricothyroid membrane is approximately 20 to 30 mm in width and 9 to 10 mm in superior-to-inferior length. In infants and children, the larynx is smaller and positioned more rostrally, making the topical landmarks of the thyroid and cricoid cartilage more difficult to identify. Furthermore, in this population, the hyoid bone may be more easily felt than the thyroid cartilage. In infants, the cricothyroid membrane is only about 3 mm in rostrocaudal length. For this reason, some medical personnel recommend that alternative techniques be employed in young children (1) (see “Indications”).

Indications

The primary indication for surgical cricothyrotomy is to achieve airway control when less invasive techniques are unsuccessful or contraindicated. In infants and children, this will occur most often when an upper airway obstruction results from an irremovable foreign body or massive edema (such as epiglottitis or Ludwig angina) or when significant maxillofacial, mandibular, oropharyngeal, or laryngeal trauma has occurred and caused significant edema or severe anatomic distortion. Usually, masseter spasm or laryngeal spasm in children can be managed by other means, such as pharmacologic

paralysis and endotracheal intubation. The use of surgical cricothyrotomy in children with known or suspected cervical spine injury is controversial. It is an option when BVM ventilation or controlled orotracheal intubation with in-line stabilization of the head and neck cannot be safely accomplished in the apneic or hypoxemic child.

paralysis and endotracheal intubation. The use of surgical cricothyrotomy in children with known or suspected cervical spine injury is controversial. It is an option when BVM ventilation or controlled orotracheal intubation with in-line stabilization of the head and neck cannot be safely accomplished in the apneic or hypoxemic child.

The major contraindication to this technique is the ability to provide adequate oxygenation and ventilation by more standard, less invasive means (see Chapters 13 to 18). Massive trauma to the larynx or the trachea, particularly transecting injury, is also a relative contraindication to surgical or needle cricothyrotomy; these techniques should be attempted under these circumstances only when other means of airway control are impossible and death is imminent. Additionally, because of the small size of the cricothyroid membrane in young children, some medical personnel suggest that this technique not be employed in children less than 5 years of age (1). Needle cricothyrotomy is preferred in younger children.

Other relative contraindications include neck trauma or edema that hinders surgical dissection or landmark identification. Known bleeding diathesis also may increase the risk of failure to obtain airway control rapidly and increase the risk of other complications as well.

Surgical cricothyrotomy most often will be performed by physicians; however, in many situations airway control must be accomplished in the field. It is therefore vital that prehospital providers be familiar with this technique or with one of the alternatives discussed in Section 2.

Equipment

The equipment necessary to perform surgical cricothyrotomy is listed in Table 26.1. As is the problem with other procedures, this technique is rarely employed in children, and the equipment available on a surgical airway tray may be inappropriate for use in children. Valuable time may be lost in an attempt to gather the proper equipment when the need for it arises. Therefore, it is important to include pediatric equipment on such trays or to develop a pediatric surgical airway tray. It is particularly important to have the proper size tracheal tubes and/or tracheostomy tubes, and a range of tube

sizes should be immediately available. Equipment necessary to perform wire-guided cricothyroidotomy can be purchased in a kit. Many facilities choose this option because it is convenient and ensures that all necessary tools will be available when the need arises. One piece of equipment should be used with caution: Standard tracheostomy tubes are designed such that the intratracheal portion has a more acute angle with the flange than does the cricothyroidotomy catheter (see Fig. 26.3D). They are, therefore, more difficult to fully insert than cricothyroidotomy catheters.

sizes should be immediately available. Equipment necessary to perform wire-guided cricothyroidotomy can be purchased in a kit. Many facilities choose this option because it is convenient and ensures that all necessary tools will be available when the need arises. One piece of equipment should be used with caution: Standard tracheostomy tubes are designed such that the intratracheal portion has a more acute angle with the flange than does the cricothyroidotomy catheter (see Fig. 26.3D). They are, therefore, more difficult to fully insert than cricothyroidotomy catheters.

TABLE 26.1 Equipment | |

|---|---|

|

Procedure

Surgical Cricothyrotomy: Standard Technique

The cricothyroid membrane should be identified below the tip or notch of the thyroid cartilage and above the cricoid cartilage. As stated previously, these structures can be difficult to palpate in young children, but the thyroid cartilage is large enough to be felt in most children. Once this structure is identified, its anterior surface should be palpated in a rostrocaudal fashion. The palpating finger should drop into the notch below the thyroid cartilage; this is the location of the cricothyroid membrane. When the thyroid cartilage cannot be identified by palpation, an alternative is to identify the hyoid bone and to then palpate caudally. Either the thyroid cartilage or the cricoid cartilage (or both) can be identified by this method.

If time permits, adequate surgical preparation and local anesthetic infiltration using lidocaine with epinephrine should be done. A vertical midline incision is made over the entire cricothyroid membrane (Fig. 26.2A). The midline incision should protect most of the major neck vessels, which are located laterally, but some venous bleeding should be anticipated. Limiting the caudad extension of the incision is necessary to avoid the highly vascular thyroid gland. The skin and subcutaneous tissue should be incised and then held open with retractors (Fig. 26.2B). After this incision, the cricothyroid membrane should be quickly palpated a second time to confirm its position. The sternohyoid muscle then should be carefully incised or separated by blunt dissection, exposing the cricothyroid membrane (Fig. 26.2C). The trachea is stabilized with either a tracheal hook or the fingers of the nonsurgical hand, and a short horizontal incision is made with the point of a No. 11 scalpel blade. The incision is made in the lower half of the membrane, near the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 26.2D). Care must be taken to direct the scalpel blade perpendicular to the frontal plane of the membrane and not to enter too deeply into the trachea, because this could result in injury to the posterior wall of the trachea and the esophagus behind it. Curved Mayo scissors or a curved hemostat is inserted into the incision, turned, and spread to widen the opening. While the blades of the scissors or hemostat are used to maintain the opening, the trachea is stabilized and lifted anteriorly, and an appropriate size tracheostomy tube or endotracheal tube is inserted between the scissor or hemostat blades and into the trachea (Fig. 26.2E). Alternatively, a tracheal hook can be inserted into the caudal portion of the incision and used to elevate the cricoid cartilage and trachea. The tube can be passed below the hook and into the trachea. The tube is secured and attached to a bag-valve device, and ventilation is assessed (Fig. 26.2F).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree