Surgical Conditions of the Vagina and Urethra

Y. Hernandez Suarez

John A. Rock

Ira R. Horowitz

DEFINITIONS

Genitoplasty—Surgical reconstruction of the external genitals.

Hematocolpos—A condition in which menstrual blood accumulates inside the vagina and distends it, most commonly associated with obstructing vaginal anomalies.

Hermaphroditism—A condition in which there is a combination of disparate or contradictory elements most commonly used to describe an individual who has both male and female sexual characteristics and organs (synonyms: intersex, androgyne).

Imperforate hymen—The hymen usually is perforated during embryonic life to establish a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule, and it usually is torn early in the prepubertal years. If canalization fails and there are no perforations, the hymen is called imperforate.

Pseudohermaphroditism—A condition in which the gonads are of one sex (genetically XX or XY), but in which the physical/phenotypical appearance is of the opposite sex. Genetically female individuals (chromosomes XX, thus with female gonads/ovaries) presenting with significant male secondary sex characteristics and genetically male individuals (chromosome XY, thus with male gonads/testes) presenting with significant female secondary sex characteristics.

OBSTRUCTIVE LESIONS OF THE VAGINA

Imperforate Hymen

Imperforate hymen is the most common obstructive congenital lesion of the female genital tract. The hymen, the junction of the sinovaginal bulbs with the urogenital sinus (UGS), is a thin mucous membrane, sometimes cribriform in appearance, composed of endoderm from the UGS epithelium. The müllerian ducts meet the sinovaginal bulbs at the most cephalad tip of the invaginating UGS. The vaginal plate elongates and canalizes to form the vagina. If the vaginal plate does not canalize, a transverse vaginal septum is the result. Canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS establishes a patent hymen. The hymen usually is perforated during embryonic life to establish a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule, and it usually is torn early in the prepubertal years. If canalization fails and there are no perforations, the hymen is called imperforate. It is usually an isolated finding with no associated anatomic anomalies.

Although variations in hymen development occur, complete blockage by the hymen of the vaginal orifice is rare, occurring in approximately 0.05% to 0.1% of newborn girls. In 1986, Mor and colleagues described the types of hymeneal shape in the newborn infant from examination performed within

the first 24 hours of life. In 53.5%, a smooth hymen with a central orifice was observed; a folded hymen with a central orifice was seen in 27%; a folded hymen with an eccentric orifice occurred in 4.5%; an anterior opening of the hymen was found in 10.8%; a posterior opening was found in 0.6%. The researchers found that 3% had hymeneal bands and 0.3% of the newborns had imperforate hymens.

the first 24 hours of life. In 53.5%, a smooth hymen with a central orifice was observed; a folded hymen with a central orifice was seen in 27%; a folded hymen with an eccentric orifice occurred in 4.5%; an anterior opening of the hymen was found in 10.8%; a posterior opening was found in 0.6%. The researchers found that 3% had hymeneal bands and 0.3% of the newborns had imperforate hymens.

Stelling and colleagues have evaluated the genetic transmission of imperforate hymen and reported that the occurrence of imperforate hymen in two consecutive generations of a family is consistent with a dominant mode of transmission, either sex linked or autosomal. Examination of newborns with a family history of imperforate hymen is of particular importance.

Symptoms

Cases that are recognized at birth present with a thin bulging membrane between the labia, which represents a mucocolpos. When the hymen is incised, the vagina is found to contain mucoid fluid that is the result of accumulated cervical secretion. This is caused by the stimulation of the infant’s cervical mucous glands by maternal estrogen in the presence of an intact hymen. Prenatal diagnosis of imperforate hymen and mucocolpos has been described with second-trimester antenatal sonography demonstrating a thin membrane that distended the vagina and spread the labia majora.

Although by performing a careful inspection of the external genitalia, an imperforate hymen may be diagnosed at any age, most commonly imperforate hymen is not detected until puberty, with girls presenting at age 13 to 15 years when symptoms begin to appear with no external evidence of menstruation. In 2005, Posner and Spandorfer reported a bimodal distribution of age at diagnosis with 43% (n = 10) of girls diagnosed younger than age 8 and 57% (n = 13) at or older than age 8. Among older girls, 100% were symptomatic with abdominal pain and/or urinary symptoms. They found that in the young girls, in 90% of cases the diagnosis was incidental. On review of the older girls’ medical records, they found that the majority lacked description of breast and pubic hair development, and almost half did not have menstrual history documented. The older group was more likely to present symptomatically and to undergo ancillary testing. They conclude that incorporating an examination of the external genitalia into routine practice of clinicians caring for children can prevent the significant delays in diagnosis of imperforate hymen, misdiagnosis, and potential morbidity associated with the latter group.

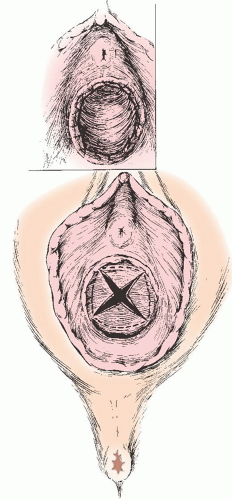

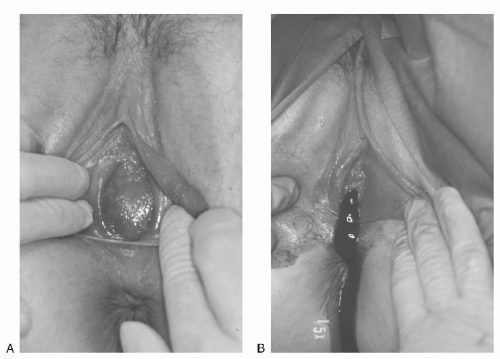

FIGURE 24.1 A: An imperforate hymen, membrane protrusion with a dark-tinged posterior representing a hematocolpos. B: Extrusion of accumulated blood at the time of incision into the membrane. |

The symptoms of imperforate hymen after the onset of puberty are due to the accumulation of menstrual blood within the vaginal outlet tract. The blood of the first few cycles is collected in the vagina, which can hold a large volume of blood without undue stretching. This accumulated menstrual blood in the vagina is called hematocolpos. The patient may feel slight fatigue and have cramping discomfort suggesting menstruation, but she has no history of any passage of menstrual blood through the vaginal outlet. Figure 24.1A shows bulging of the imperforate hymen, which may be dark in color because of occult blood showing through the stretched mucous membrane; Figure 24.1B shows extrusion of accumulated blood after the hymen is incised.

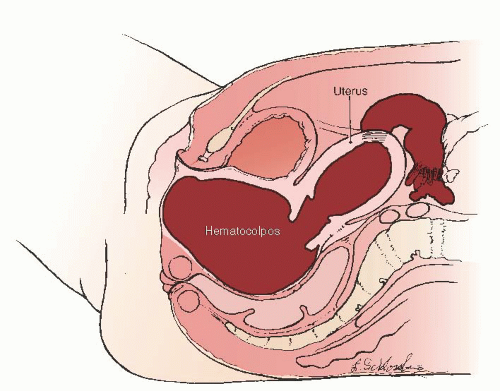

With continuing menstruation, the vagina distends, the cervical canal dilates, and hematometra (the filling of the endometrial cavity with blood) occurs. When the intrauterine pressure reaches a certain point, retrograde passage of blood into the tubes causes hematosalpinx. Rarely, blood passes freely into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 24.2) causing all the symptoms and signs of peritonitis.

The most common symptoms of vaginal overdistention are lower abdominal pain, discomfort in the pelvis, and pain in the lower back. A tender mass may be palpable suprapubically, the result of uterine enlargement and upward displacement, bladder distention, or both. Hematocolpos should be included in the differential diagnosis of amenorrheic girls presenting with persistent lower back pain. Irritation of the sacral plexus is believed to be the etiology of this referred pain pattern. The lower abdominal discomfort often is aggravated on defecation, and if extensive blood accumulation occurs in the vagina,

constipation may result from pressure and obstruction of the underlying rectum. Urination can be difficult as a result of pressure of the distended vagina, which can compress the urethra and prevent emptying of the bladder; urinary obstruction can ensue. Bladder symptoms can present as cramplike pains in the suprapubic region, along with symptoms of dysuria, frequency, and urgency; overflow incontinence may eventually develop, and hydronephrosis is a rare complication. Girls presenting with severe dysmenorrhea and duplicate vagina and didelphic uterus should be evaluated for unilateral imperforate hymen.

constipation may result from pressure and obstruction of the underlying rectum. Urination can be difficult as a result of pressure of the distended vagina, which can compress the urethra and prevent emptying of the bladder; urinary obstruction can ensue. Bladder symptoms can present as cramplike pains in the suprapubic region, along with symptoms of dysuria, frequency, and urgency; overflow incontinence may eventually develop, and hydronephrosis is a rare complication. Girls presenting with severe dysmenorrhea and duplicate vagina and didelphic uterus should be evaluated for unilateral imperforate hymen.

FIGURE 24.2 Hematocolpos, hematometra, hematosalpinx, and hemoperitoneum consequent to an imperforate hymen. |

Pelvic ultrasound should be performed in the evaluation of imperforate hymen particularly prior to surgical intervention. Concomitant diagnostic laparoscopy in patients with imperforate hymen has not demonstrated an association with pelvic endometriosis, and laparoscopy should not be included in the standard evaluation of imperforate hymen.

Treatment

Approach to the surgical management of imperforate hymen requires cultural sensitivity. The importance of hymeneal integrity varies among cultures and religions. Options should be carefully explained to patients and their families, and the choice of surgical approach should be reached through shared decision making. In the patient diagnosed in infancy, surgery may be delayed until adolescence to ensure optimum long-term vaginal functionality and reduce the small risk of repeat surgery. The goals of surgical management of imperforate hymen are both long and short term. In the short term, the obstruction of the vagina is alleviated. In the long term, satisfactory cosmesis, sexual function, and fertility are preserved.

In the standard approach, the hymenal membrane is incised in a stellate fashion, preferably at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions. The quadrants of the hymen are then excised, and the mucosal margins are approximated with fine delayed absorbable suture (Fig. 24.3). To prevent scarring and stenosis, the hymenal tissue should not be excised too close to the vaginal mucosa. The vagina should be carefully drained with a suction probe. In patients in whom hematometra is present, all intrauterine instrumentation should be avoided (Fig. 24.2), as there is significant risk of perforating the thin, overstretched uterine wall. Patients should be followed for 2 to 3 weeks to ensure adequate resolution of the hematometra. Rarely, secondary dilatation of the cervix may be needed.

For patients in whom the perception of hymeneal “integrity” is important, the procedure may be modified to exclude the excision of the hymen. A simple vertical incision of the hymeneal membrane is performed with oblique suturing of the hymen to form an annular opening. Sutures may be avoided with the placement of a Foley catheter and topical estrogen cream for 2 weeks postoperatively. These approaches have anecdotally resulted in satisfactory cosmesis and defloration.

Rock and colleagues followed pregnancy success subsequent to the surgical correction of imperforate hymen between 1945 and 1981 at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Twenty-two patients of mean age 14.7 years were admitted for surgical correction of imperforate hymens. Associated anomalies, including urinary tract anomalies, were rare. Thirteen patients subsequently conceived, and 10 patients were observed to have living children. Liang and colleagues in 2003 reported on the long-term postoperative evaluation of 15 patients with imperforate hymen. They conducted questionnaires and telephone interviews regarding sexuality, fertility, menstrual problems, micturition, and defecation. The mean postoperative follow-up was 8.5 years, with the mean age at diagnosis being 13.2 years. The women reported being markedly relieved of their presenting symptoms after hymenectomy. There were some who reported having irregular menstruation, and 6/15 reported dysmenorrhea. The authors reported that most patients fared well in terms of fertility and sexual function. It is important to counsel patients and their families about the favorable prognosis of fertility and pregnancy in women with correction of imperforate hymen.

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Transverse vaginal septum is a rare cause of congenital vaginal obstruction. Presenting symptoms are identical to imperforate hymen, but diagnosis is frequently delayed in the setting of a normal vulvovaginal exam. Transverse vaginal septum is diagnosed on pelvic ultrasound with hematocolpos identified cephalad to the septum. Concomitant uterine and renal malformations have been described. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in identifying the anatomy. Joki-Erkkila and Heinonen in 2003 identified 26 women with obstructive vaginal malformations. Thirteen underwent incision of an imperforate hymen and 3 excision of a complete transverse vaginal septum, with a mean follow-up period of 13 years. The remaining 10 had obstructive hemivagina and incision of a “longitudinal” vaginal septum with a mean follow-up period of 16 years. The women with transverse obstruction (imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum) were diagnosed within a month from their primary symptoms compared with 27 months for those with longitudinal obstruction. None with imperforate hymen required reoperation, but 2/3 with transverse vaginal septum did for vaginal constriction, and 3/10 with longitudinal vaginal septum had reexcision of their septum. All of the 10 women with longitudinal obstruction had uterine and renal malformations, whereas in those with a transverse vaginal obstruction, only 6 underwent renal evaluation, and of these, 2 had double ureters. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding was reported by 19% of those in the transverse group and 40% of those in the longitudinal obstruction group, dyspareunia was reported in 30% of the transverse and none in the longitudinal, and dysmenorrhea was reported in 19% of transverse and 20% of longitudinal. No endometriosis was found in women who subsequently had a laparotomy or laparoscopy (18/26). In the 14 who were attempting to conceive, difficulty with fertility was not diagnosed. Twenty-five (89%) out of twenty eight pregnancies ended in delivery, the live birth rate of the longitudinal group being 82%, and 94% in those with transverse obstruction. The authors concluded that accurate diagnosis, along with adequate treatment, can reduce the need for reoperations and that no specific longterm clinical gynecologic symptoms were identified in these women with obstructing vaginal anomalies.

Sequelae of Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” The WHO estimates that more than 100 million worldwide have undergone some type of FGM. It is estimated that approximately 250,000 girls and women with FGM are currently living in the United States. Female genital mutilation is practiced in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, and is most commonly performed in puberty. Late complications of FGM include strictures, obstruction, and fistula formation. Complete obstruction of the vagina resulting in hematocolpos and hematometra has been reported. Women with FGM may seek gynecologic consultation to alleviate dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea or in preparation for childbirth. Defibulation is a vertical incision made to open scarring and reconstruct external genitalia. In a study by Nour et al. at the African Women’s Health Center at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 40 women were identified as having undergone defibulation between 1995 and 2003. Indications for defibulation were pregnancy (30%), dysmenorrhea (30%), apareunia (20%), and dyspareunia (20%). Almost 50% were found to have an intact clitoris underneath the scar. More than 90% of women stated they would highly recommend the procedure to others. 100% were satisfied with appearance and sexual function. The American Congress of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists has prepared a toolkit for clinicians caring for patients with FGM that includes photographs and detailed instructions.

Obstetricians and Gynecologists has prepared a toolkit for clinicians caring for patients with FGM that includes photographs and detailed instructions.

Anomalies of the External Genitalia and Vagina

Sexually Ambiguous External Genitalia

Sexually ambiguous external genitalia defects of the UGS are remarkably constant in appearance, regardless of the etiology of the anomaly. Such genitalia differ only in their degree of malformation and occupy a range of positions somewhere intermediate to the genitalia of a normal female and that of a normal male. These anomalies can be anatomically identical to each other, whether their etiologic factor is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), male hermaphroditism, true hermaphroditism, or some other intersex syndrome. External genitalia proceeds along the female lines except in the presence of some virilizing influence acting on the developing embryo (i.e., androgens). The conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone by 5α-reductase activity occurs in the skin of the external genitalia and UGS in early gestation. Masculinization of the external genitalia ensues in the presence of functional androgens regardless of genetic sex. In the case of female pseudohermaphroditism— XX chromosomes in the presence of a virilizing influence—the fusion of the scrotolabial folds may be sufficient to obscure or conceal the vagina from the outside or even to entirely suppress its formation. The urethra can be formed for varying distances or along the entire length of the phallus. Therefore, the operative procedure for reconstruction of ambiguous genitalia into feminine genitalia does not vary in its essential elements, regardless of the cause of the intersexuality. The common goals for the female reconstruction of ambiguous genitalia include reduction of clitoral size, creation of labia minora, and exteriorization of the vagina.

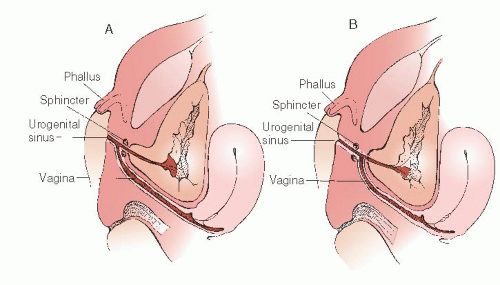

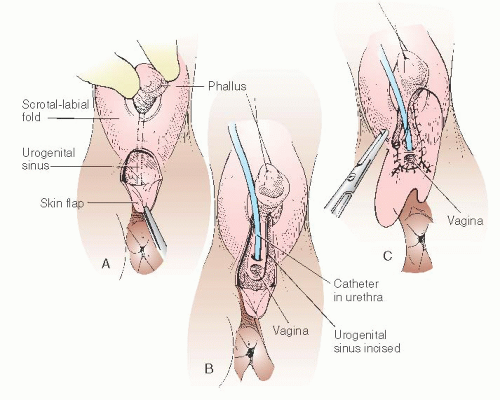

Any reconstruction of the external genitalia with the objective of producing normal female appearance and function requires a full understanding of the surgical anatomy. It is essential to accurately identify the site of communication of the vagina with the UGS. In their classic paper in 1969, Hendren and Crawford recognized the variability of the communication of the vaginal insertion into the UGS. Figure 24.4 illustrates the spectrum of vaginal communication with the urethra, with Figure 24.4A representative of a low distal communication (infrasphincteric) and Figure 24.4B representative of a high proximal communication (suprasphincteric). In 95% of cases, the vaginal communication is in relation to the caudal UGS derivatives (infrasphincteric) with the vagina communicating with that portion of the UGS that in a man gives rise to the membranous portion of the male urethra and that in the woman becomes the vaginal vestibule. If this usual relation is confirmed at surgery, the persistent, anomalous UGS may be incised to the vaginal communication without fear of disturbing the urinary sphincter. In less than 5% of cases, the vagina communicates high, with the portion of the UGS that becomes the prostatic urethra in the man or the entire urethra in the woman (suprasphincteric). Knowledge of the possible variants in communication of the vagina with the UGS is critical before entertaining surgical correction. Preoperatively, genitography showing the relationship of the UGS, urethra, vagina, and bladder may be helpful. Contrast is injected retrogradely through the perineal meatus of the UGS. Delineation of this anatomy can be elucidated at the time of surgery with the use of endoscopy to evaluate where the vagina communicates with the UGS. In 1989, Bargy and colleagues described the anatomic lesions in the intersexual states based on clinical and anatomic observations.

One objective of the reconstruction procedure for external genitalia is to delay the procedure until the anomalous structures are of a size to permit easy identification of all structures. As observed by Azziz and coworkers, vaginal repair may be delayed until menarche, when maturity and the desire for sexual activity are usually well established. There is present debate in the need for early reconstruction for the sole purpose of cosmesis to prevent embarrassment or anxiety to the patient’s family. Crouch and Creighton revisited the longstanding dictum of early surgical correction of ambiguous genitalia for intersex conditions. They report that some advocate the “one-stage” procedure in infancy, but that others advocate deferral of vaginal surgery until after puberty, especially given that many patients require further surgery at adolescence. It has been believed that the intersex child may be psychologically damaged by the “appearance” of uncorrected external genitalia if not performed at infancy, but unfortunately to date little research on this exists.

Most hermaphrodites reared as girls have a vagina or vaginal pouch, although in some instances, it is rudimentary. Only rarely is there no vagina, despite ambiguity of the external genitalia. The choice of operative procedure must conform to the observed anatomy. Thus, these choices are considered in the context of several categories based on anatomic structure of the anomaly.

When the Vagina Is Present and the Vaginosinus Communication Is Low

The basic operation is, in essence, a modification of one described at length by Young that was previously performed successfully by various surgeons, notably in Europe. Patients with adrenal hyperplasia usually require only reconstruction of the external genitalia. However, when exploratory laparotomy is necessary to remove contradictory sex structures in other types of intersexuality or to establish the diagnosis, reconstruction of the genitalia may be considered at the same operation.

If an operation is deemed necessary at a very young age, the structures can be so small that it is impossible to introduce a finger into the UGS, and all tissues must be grasped throughout the operation with fine delicate tissue forceps. Operating loupes (2.5 to 3) are of great benefit to the surgeon. Small bipolar forceps and microscissors are also useful. Fine 5-0 or 6-0 synthetic absorbable sutures on an atraumatic needle are used throughout the procedure.

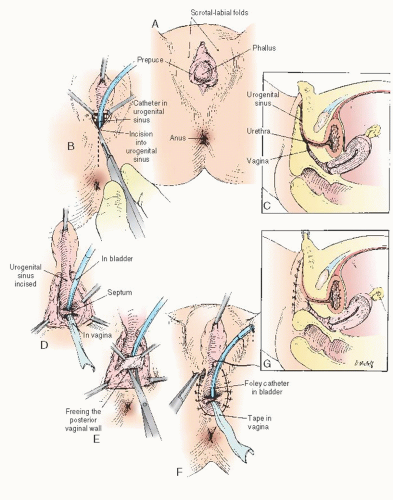

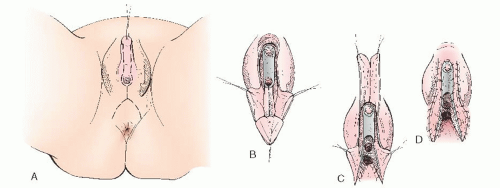

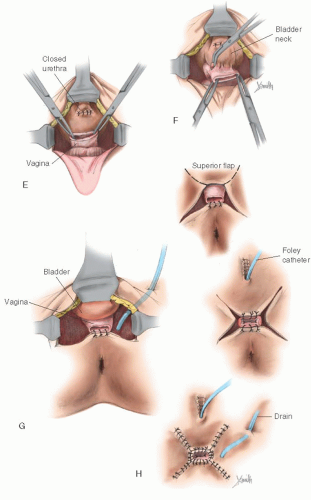

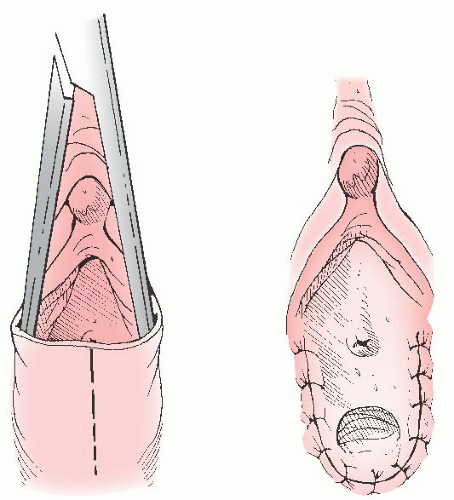

In cases of simple labial fusion, a cutback vaginoplasty (Fig. 24.5) would be sufficient to restore “normal” female genital anatomy. In cases of low vaginal confluence with the UGS (Fig. 24.4A), reconstruction may be done either by freeing the posterior vaginal wall and suturing up to the perineal external opening (Fig. 24.6) or—if a patient has copious subcutaneous fat and difficulty exists in approximating the vagina to the perineal skin—by use of a posterior flap technique, as used by Fortunoff and coworkers (Fig. 24.7).

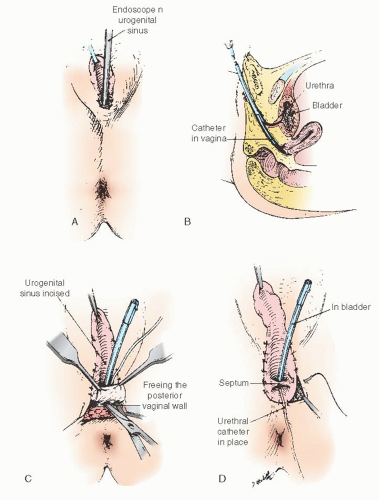

Initially, the UGS may be thoroughly investigated with a small McCarthy panendoscope to determine accurately the position and size of the vaginal communication. If a sound or catheter can be easily introduced into the meatus of the UGS and into the vagina, use of the endoscope may be omitted. Special care is needed not to introduce the sound into the urethra. A sound accidentally introduced into the urethra poses the danger of incising the distal urethral meatus. After the UGS is incised (to within 2 or 3 cm of the anus), the urethral orifice may be identified (Fig. 24.6A, B). A small Foley catheter may then be introduced through the urinary meatus for purposes of identification throughout the remainder of the operation. To attach the edges of the vagina to the skin, it is usually necessary to free the vagina posteriorly and laterally to secure sufficient mobilization so that these structures meet with no tension. It is unnecessary to free the vagina anteriorly, because this requires its separation from the urethra. Sufficient mobilization can ordinarily be obtained by lateral and posterior dissection. When sufficient freedom has been attained, the edges of the vagina may be secured to the skin with interrupted 5-0 sutures on an atraumatic reverse cutting needle. In the infant, four or five sutures around the edge of the vagina are usually sufficient. The edges of the incised sinus membrane may then be sutured to the skin anteriorly (Fig. 24.6D-G). A small sponge impregnated with petroleum jelly may be introduced into the vagina to maintain its patency during the healing process. The indwelling catheter may be left in place for a few days until edema of the surrounding structures has subsided. An indwelling catheter is particularly useful in children with metabolic disorders that require accurate urine collection. A pressure dressing for 24 hours reduces the incidence of incisional hematoma.

FIGURE 24.5 In cases of simple labial fusion, a cutback vaginoplasty is sufficient to restore “normal” female genital anatomy. |

Figure 24.7 illustrates vaginoplasty with a posterior flap as advocated by Fortunoff and is useful in cases with anticipated difficulty in bringing the vaginal orifice to the outside. Briefly, a posterior-based U-flap is drawn, with corners on either side of the perineal body near the rectum (Fig. 24.7A-C). This flap must be wide enough for tension-free anastomosis. This posterior flap is dissected in the midline and is carried out between the rectum and UGS.

Sutures are individually placed through the posterior-based flap and into the split posterior vagina. Sutures are tied after all have been placed. Because the anterior wall is not disturbed, no anterior flap is required. Finally, the phallic skin is divided in the midline and moved inferiorly to create the labia minora.

Surgical reconstruction of an enlarged clitoris has undergone significant evolution. Traditionally, the clitoris was simply amputated, and a nonfunctioning cosmetic clitoris was fashioned. Although several children so treated now have normal adult sexual function, the literature is lacking in followup data on large patient groups. Surgical efforts now focus on concealment, plication, resection, and reduction, with an attempt to provide a normal cosmesis without sacrificing sensation or vascularity of the glans.

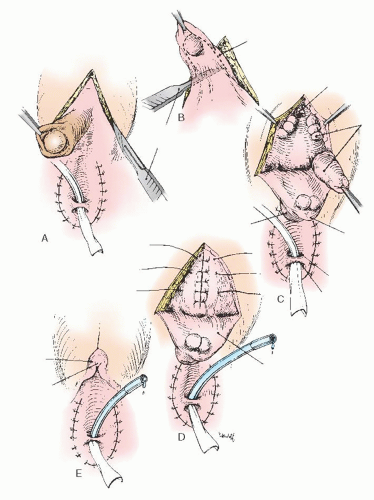

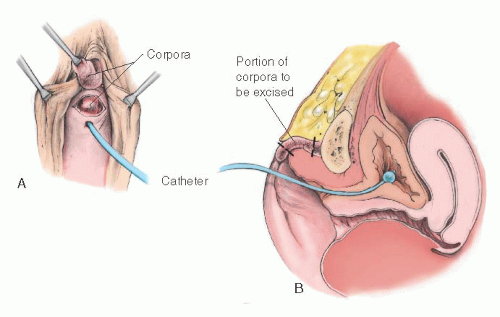

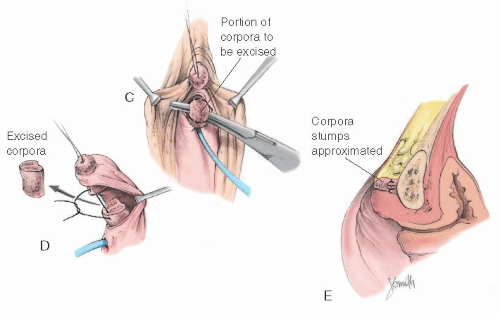

The clitoral flap technique has provided a somewhat better cosmetic result than simple amputation. This procedure attempts to preserve a shell of the glans on a pedicle flap. The shaft of the clitoris is subtotally resected, and the stumps are reanastomosed (Fig. 24.8). The nerve supply to the glans is severed during this procedure, with the result that sensation in the glans is diminished. Sexual function, however, seems to be satisfactory.

Rajfer and colleagues have suggested a dorsal approach to the subtotal resection of the corpora (Fig. 24.9), which has the advantage of preserving the ventral nerve supply and which should preserve sensation in the glans. This approach is theoretically desirable and can be recommended for suitable cases. As mentioned earlier, however, lack of clitoral sensation does not seem to significantly affect the later sexual behavior of patients treated by procedures that sever the dorsal nerves to the glans.

In 1999, Baskin and colleagues described the anatomic studies of the human clitoris. As in the human penis, the nerves in the clitoris form an extensive network surrounding the tunica

of the corporeal body with a nerve-free zone at the 12-o’clock position. The normal clitoris has corporeal bodies that are smaller but analogous to those of the penis. The surgeon should be mindful of their function if extensive resection is considered with care to preserve the dorsal aspect of the glans.

of the corporeal body with a nerve-free zone at the 12-o’clock position. The normal clitoris has corporeal bodies that are smaller but analogous to those of the penis. The surgeon should be mindful of their function if extensive resection is considered with care to preserve the dorsal aspect of the glans.

FIGURE 24.7 A posterior flap technique for when there is difficulty bringing the vaginal orifice to the outside. |

FIGURE 24.9 Clitoral reduction with the corpora exposed through a dorsal incision (operation of Rajfer et al.). A-C: Corpora are approached and removed through a posterior incision in the phallus. |

FIGURE 24.9 (Continued) D: Diagram of the excised portion of the corpora. E: The corpora are removed and stumps approximated. |

Rink and Adams in 1998 reviewed feminizing genitoplasty. They advocated clitoral reduction without sacrificing sensation or vascularity of the glans, recommending a subtunical reduction of erectile tissue as described by Kogan and colleagues in the 1980s. The glans is preserved with its neurovascular supply intact along Buck fascia and the dorsal tunic of the corpora, yet the cavernous erectile tissue is excised. Figure 24.10 illustrates this surgical management; additionally, the phallus is degloved, and this skin is used to create the labia minora. An incision is made around the corona of the phallus and continued inferiorly around the urethral meatus. Preservation of this meatal plate improves cosmesis and increases blood supply to the glans. The neurovascular bundle is identified, with lateral incisions into the tunica of the corpora along the phallus from the glans backward proximal to the corporal bifurcation. The cavernous erectile tissue is dissected from the inferior aspect of the dorsal tunic and excised, and the proximal and dorsal corpora are suture ligated. The glans is secured to the inferior aspect of the pubis or to the corporal stumps.

In a pilot study of six women in 2003, Crouch and colleagues reported on genital sensation after feminizing genitoplasty for women with CAH. These women were assessed for thermal, vibratory, and light touch sensory thresholds in the clitoris and vagina using a genitosensory analyzer and Von Frey filaments. Highly abnormal results for sensation in the clitoris were found in the six women studied. In three who had an introitus capable of admitting a vaginal probe, the vaginal sensory data was considered normal. Given an abnormal clitoral sensation and normal vaginal sensation, the authors hypothesize that the abnormal clitoral findings may result from the surgical reconstruction rather than an effect of CAH. A self-administered sexual function assessment revealed that these women had sexual difficulties, particularly in the areas of infrequency of intercourse and anorgasmia. The authors voiced their concerns with the stated superiority of modern surgery. They stated that the vascularity of the glans remains vulnerable and that the risk of damage to the neurovascular bundles is inherent in any technique that

entails their separation from the corporal tissue. They concluded that even after seemingly successful clitoral reduction, the sensory function is significantly impaired, and this should be taken into consideration during counseling. Larger studies are presently under way to further evaluate these findings.

entails their separation from the corporal tissue. They concluded that even after seemingly successful clitoral reduction, the sensory function is significantly impaired, and this should be taken into consideration during counseling. Larger studies are presently under way to further evaluate these findings.

When the Vaginal Orifice Is Obscured

As mentioned previously, preoperative identification and catheterization or sounding of the vaginal orifice is key to the performance of a successful, one-stage procedure. When the vagina cannot be located by sounding, it sometimes can be seen by endoscopy. When sounding and vision both fail, an attempt before surgery to introduce a small (no. 4 or 5) ureteral catheter into the vagina by blindly probing through the endoscope along the posterior wall of the UGS may assist in the identification of the vagina. Sometimes, this catheter finds the orifice. If so, it may be left within the vagina as a guide during surgical exposure of the area (Fig. 24.11). If the vaginal orifice cannot be located, a planned two-stage operation is indicated. The objective of the first stage is to obtain cosmetically satisfactory female genitalia by reducing the clitoris and partially excising the UGS without exteriorizing the vagina. During the planned second stage, exteriorization of the vagina can be performed. The second stage should be postponed until identification of the vaginal orifice by sounding becomes possible. This may require waiting for puberty for estrogenization of the area. If dilators are needed for patency postoperatively, this surgery should be delayed until the girl is sufficiently mature for their appropriate use. This will maximize the success of the reoperation.

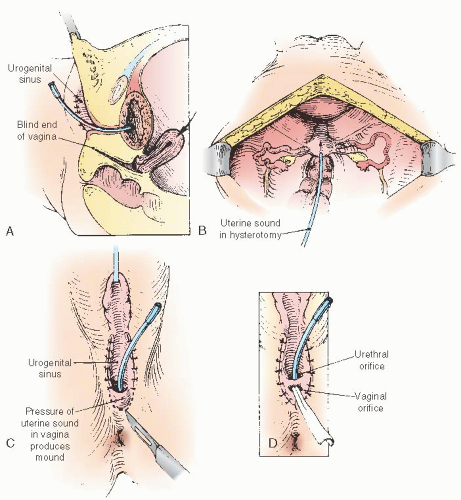

When the Vaginosinus Communication Is Blocked

Rarely does the vagina not communicate with the UGS. The vagina with the UGS is homologous with the hymenal area, and the hymen rarely is imperforate in an otherwise normal woman. For such a circumstance, we have found it helpful to pass a uterine sound downward through the fundus via hysterotomy into the vagina, thus forming a protrusion on the perineum. With such a guide, the edges of the vaginal epithelium can be located and sutured to the skin (Fig. 24.12). Until the uterus enlarges somewhat from its infantile state, the cavity is not large enough to accommodate even a uterine sound. Therefore,

if such an operation is contemplated, it should not be done until there is a palpable enlargement of the uterus at the onset of puberty. Evaluation of uterine volume sonographically as a predictor of uterine size adequacy may be helpful.

if such an operation is contemplated, it should not be done until there is a palpable enlargement of the uterus at the onset of puberty. Evaluation of uterine volume sonographically as a predictor of uterine size adequacy may be helpful.

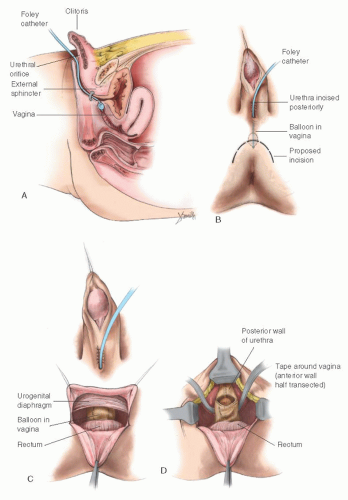

When the Vaginosinus Communication Is High

Hendren has been especially interested in patients whose vaginosinus communication involves the proximal urethra (suprasphincteric). He has advocated an operation that disconnects the vagina from the urethra and repositions the vaginal orifice in the perineum, the “pull-through” vaginoplasty. In his hands, this procedure seems to have been satisfactory for some patients. The procedure requires positioning the new vaginal orifice in the perineum (Fig. 24.13). The vast majority of patients with ambiguous external genitalia and a vagina have a vaginosinus communication well distal to the proximal urethra (infrasphincteric), and consideration of the procedure advocated by Hendren is not necessary. In patients in whom the vagina enters the UGS proximal to the external sphincter, the pull-through vaginoplasty of Hendren and Crawford or the method described by Passerini-Glazel can be used to prevent incontinence. Hendren and Crawford’s vaginal pullthrough remains the basis for reconstruction today. Modification to this procedure has evolved in an attempt to decrease the complexity and decrease the tendency of an isolated vagina toward stenosis. Rink and coworkers have favored a one-stage procedure using a perineal prone approach with no division of the rectum.

Results of Revision of External Genitalia

Among 28 patients with adrenogenital syndrome and good follow-up treated at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 22 (87.6%) needed further vaginal reconstructive surgery to achieve an adequate vaginal size to allow comfortable intercourse. Of the 22 patients, 5 had undergone more than 1 surgical attempt at reconstruction. The mean age of patients undergoing repeat procedures was 7.1 years. The mean age at first surgery for the whole group was 23.6 months. Vaginal reconstructive surgery was performed on 18 of these patients and was successful in 13 (72%) of the procedures. It generally is recommended that exteriorization of the vagina be postponed until near puberty, when feminization occurs and the young woman is sufficiently mature to comply with a postoperative dilatation program. The results of exteriorization performed during infancy must be followed up carefully for evidence of narrowing. In 1997, Costa and colleagues evaluated the vaginal size and sexual activity after different techniques of feminization of external genitalia in patients with pseudohermaphroditism. In their series of patients, all who underwent clitoroplasty reported orgasms, and 29% of the patients who had clitoridectomy reported no orgasms. Fifty percent of the patients who submitted to neovaginoplasty reported pain or bleeding during sexual intercourse. Satisfactory sexual intercourse was reported by 87% after vaginal dilation with acrylic molds.

In 2000, Krege and colleagues reported on the long-term follow-up of female patients with CAH from 21-hydroxylase deficiency, with special emphasis on the results of vaginoplasty.

They reported that the main problem during the long-term follow-up was intravaginal stenosis, with all those affected—9 of 25 (36%)—having undergone a single-stage procedure early in life to correct ambiguous genitalia (mean age, 4.7 years; range, 2 to 9 years). The authors suggested that vaginoplasty should be undertaken at the beginning of puberty, because higher estrogen levels may prevent stenosis and dilatation may be performed. In addition, 16 patients answered questionnaires that included psychological profile, and the researchers found that 14 had problems with their overall body image. Patients with correction of vaginal stenosis were particularly anxious about sexual intercourse and had problems with orgasm. Creighton and colleagues in 2001 retrospectively evaluated the cosmetic and anatomical outcomes of 44 adolescent patients who had undergone feminizing surgery for ambiguous genitalia during their childhood. The authors reported that cosmetic results were judged as poor in 18 (41%) and that 43/44 (98%) required further treatment to the genitalia for cosmesis, tampon use, or intercourse. Of the genitoplasties planned as onestage procedures, 23/26 (89%) required further major surgery.

They reported that the main problem during the long-term follow-up was intravaginal stenosis, with all those affected—9 of 25 (36%)—having undergone a single-stage procedure early in life to correct ambiguous genitalia (mean age, 4.7 years; range, 2 to 9 years). The authors suggested that vaginoplasty should be undertaken at the beginning of puberty, because higher estrogen levels may prevent stenosis and dilatation may be performed. In addition, 16 patients answered questionnaires that included psychological profile, and the researchers found that 14 had problems with their overall body image. Patients with correction of vaginal stenosis were particularly anxious about sexual intercourse and had problems with orgasm. Creighton and colleagues in 2001 retrospectively evaluated the cosmetic and anatomical outcomes of 44 adolescent patients who had undergone feminizing surgery for ambiguous genitalia during their childhood. The authors reported that cosmetic results were judged as poor in 18 (41%) and that 43/44 (98%) required further treatment to the genitalia for cosmesis, tampon use, or intercourse. Of the genitoplasties planned as onestage procedures, 23/26 (89%) required further major surgery.

Davies and colleagues in 2005 reported on urinary symptoms in adult women with CAH. The authors reported on

19 women with CAH, of whom 16 had childhood feminizing genital surgery, and compared them with age-matched women without CAH. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (BFLUTS) questionnaire was given to all of the women. Sixty-eight percent of the women with CAH reported urge incontinence compared with 16% of controls (P = 0.003). Stress incontinence was present in 47% of CAH and 26% of the controls. Nine of the CAH women reported that their urinary symptoms had an adverse effect on their lives, whereas only one of the controls did (P = 0.008). The authors concluded that women with CAH are more likely to have urinary symptoms than controls. It is important to emphasize that it is not known whether these results are associated with the surgical procedures that the women underwent or an effect of CAH itself. For counseling purposes, this information is important because in two thirds of these CAH women, urinary symptoms persisted.

19 women with CAH, of whom 16 had childhood feminizing genital surgery, and compared them with age-matched women without CAH. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (BFLUTS) questionnaire was given to all of the women. Sixty-eight percent of the women with CAH reported urge incontinence compared with 16% of controls (P = 0.003). Stress incontinence was present in 47% of CAH and 26% of the controls. Nine of the CAH women reported that their urinary symptoms had an adverse effect on their lives, whereas only one of the controls did (P = 0.008). The authors concluded that women with CAH are more likely to have urinary symptoms than controls. It is important to emphasize that it is not known whether these results are associated with the surgical procedures that the women underwent or an effect of CAH itself. For counseling purposes, this information is important because in two thirds of these CAH women, urinary symptoms persisted.

Historically, it has been assumed that psychosexual development of infants with intersex disorders is mostly due to rearing rather than being intrinsic. Over the past decade, the role of testosterone imprinting of the fetal brain has been studied to evaluate the role of this hormone in determining male sexual orientation. Studies in the 1990s of girls with CAH have confirmed that such children engage in more rough-and-tumble

play than their affected peers and that difficulties with adjustment to their assigned sex may exist. Nonetheless, few studies have been conducted to address the social, psychological, and sexual outcomes for affected adolescents and adults, although it appears that most function in the normal range and are well adjusted. The majority of girls appear not to overtly demonstrate sexual identity problems.

play than their affected peers and that difficulties with adjustment to their assigned sex may exist. Nonetheless, few studies have been conducted to address the social, psychological, and sexual outcomes for affected adolescents and adults, although it appears that most function in the normal range and are well adjusted. The majority of girls appear not to overtly demonstrate sexual identity problems.

Ozbey and coauthors reported on the experience of sex (re)assignment in genotypic female (46XX) patients with CAH when complicated by delayed presentation and inadvertent assignment. They reported on 70 patients with CAH who between 1983 and 2002 were counseled for sex assignment. They evaluated age at diagnosis and operation, the degree of virilization, parental consanguinity, and the sex preference of the families as factors determining sex (re)assignment decision-making. Forty-one of 70 (59%) presented after the neonatal period, and in these cases, all of the parents had assumed or were advised of a sex based on external genitalia appearance. Forty-nine of 70 were reared as girls, and 21 were reared as “boys.” Of these 21 “boys,” only 9 could be reassigned as girls (mean age, 7.9 months), and the other 12, with mean age at presentation of 55.8 months, were reared as “boys” in compliance with the parents’ and the study group’s decision. These “boys” underwent appropriate masculinizing reconstructive surgery. They concluded that age of presentation was critical for the ability to correctly assign the sex of patients with CAH.

Secondary Operations

A secondary operation on the vaginal outlet may be required. This is generally the case if the basic operation is deliberately accomplished in two stages, whatever the reason. A secondary operation may be indicated, for example, when an infant’s vaginal orifice is not readily identifiable, yet it seems desirable to construct cosmetically acceptable female genitalia at a very early age. Care should be taken when considering the appropriate age for performing a clitoroplasty. Some have recommended that this can be done in the newborn and that the vagina may be exteriorized at puberty as a second operation. Alizai and colleagues reported on the outcome of feminizing genitoplasty in 14 postpubertal girls (mean age, 13.1 years) with CAH. These girls were assessed under anesthesia by a pediatric urologist, plastic/reconstructive surgeon, and gynecologist. Thirteen of fourteen had previously undergone feminizing genitoplasty in early childhood. The authors reported that the outcome of clitoral surgery was unsatisfactory (clitoral atrophy or prominent glans) in six of the girls. Additional vaginal surgery was necessary for normal comfortable intercourse in 13 of the girls. In the girls with a history of vaginal reconstruction in infancy, fibrosis and scarring were prominent. The authors concluded that these results were disappointing, even in the girls who had their surgery performed by specialist surgeons. The authors highlighted the importance of late follow-up and the challenges in the prevailing assumption that total correction can be achieved with a single-stage operation in infancy. When the complete operation is attempted at an early age, the vagina is sometimes not satisfactorily exteriorized. Vaginal stenosis may require reconstruction at the time of puberty (Fig. 24.14). In this circumstance, there usually has been a failure to carry the midline incision far enough posteriorly, and a second procedure is required to complete the first one by continuing the midline incision far enough posteriorly.

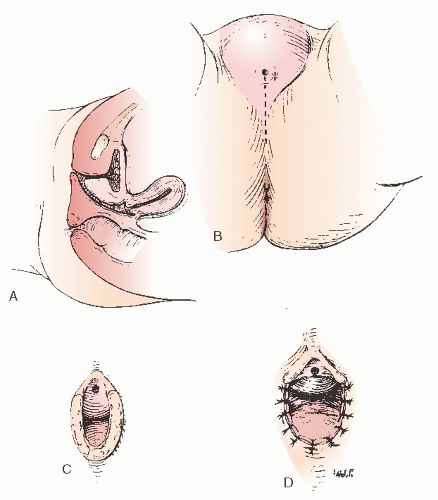

In other cases, contraction at the vaginal outlet may occur even if the operation is adequately performed. A minor revision of the vaginal orifice is required to enlarge the vaginal orifice by making an incision in the midline and closing it at 90 degrees to the original axis of the incision (Fig. 24.15). In some instances, it may be necessary to create flaps to enlarge the vaginal orifice (Fig. 24.16).

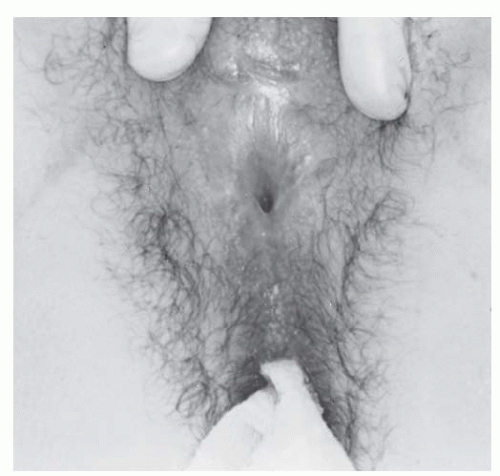

FIGURE 24.14 External genitalia of a 15-year-old patient with vaginal stenosis. Revision of the external genitalia, including an exteriorization of the vagina, had been performed in infancy. |

It should be emphasized that simple exteriorization of the lower vaginal tract can be combined with cosmetic correction of virilized external genitalia in infancy, but in most cases, it is best to defer definitive reconstruction of the intermediate or high vagina until after puberty.

Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex

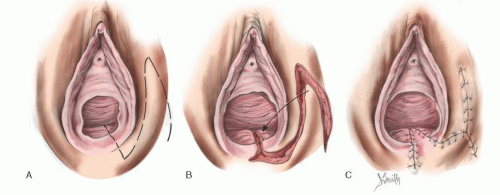

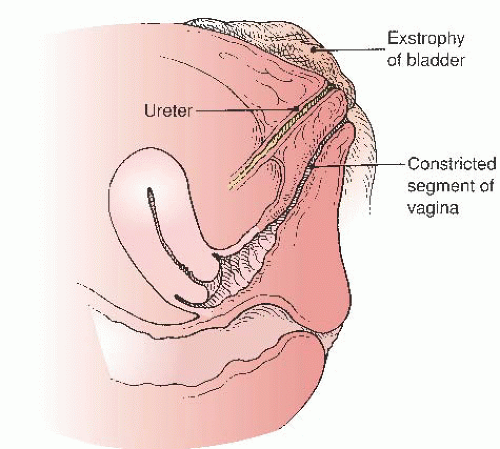

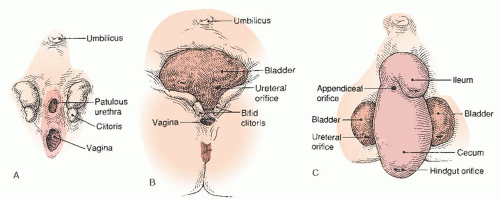

Exstrophy-epispadias complex (ECC) is a rare congenital anomaly occurring in live births in a 1:25,000 to 1:40,000 ratio. There is a male predominance over females in a ratio of about 2:1. Classic ECC is characterized by (a) absence of the lower anterior abdominal wall, (b) absence of the anterior wall of the bladder so that the posterior bladder wall and the ureteric orifices are exposed, (c) a poorly defined bladder neck and urethra, and (d) wide separation of the pubic symphysis. A genital abnormality typically present in girls with bladder exstrophy is anterior displacement and narrowing of the vagina (Fig. 24.17) and separation of the clitoris into two distinct bodies (Fig. 24.18).

Bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, and epispadias are variants of the ECC. These defects have been attributed to failure of the normal process of ingrowth of mesoderm and the consequent lack of reinforcement of the cloacal membrane. The normal cloacal membrane is bilaminar and occupies the caudal end of the germinal disc. An ingrowth of mesenchyme between the ectodermal and endodermal layers of the cloacal membrane forms the lower abdominal wall musculature and the pelvic bones. After mesenchymal ingrowth occurs, descent of the urorectal septum divides the cloacal membrane into the bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly. The urorectal septum eventually meets with the posterior remnant of the cloacal membrane, which perforates to form the anal and UGS openings. The paired genital tubercles migrate medially and fuse in the midline anterior to the

cloacal membrane before perforation. Without its normal support from mesenchymal derivatives, the cloacal membrane is subject to premature rupture. Depending on the extent of the infraumbilical defect and the stage of development when rupture occurs, bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, or epispadias develops (Fig. 24.19). Jones reviewed the records of all female patients diagnosed with bladder exstrophy at Johns Hopkins Hospital over a 20-year time span. Of 18 patients with adequately described external genitalia, 13 had small, anteriorly displaced vaginal orifices, and the remaining five patients had vaginal orifices of normal size and location. In this series, only a third of patients with ECC demonstrated the defect of narrowing of the vagina.

cloacal membrane before perforation. Without its normal support from mesenchymal derivatives, the cloacal membrane is subject to premature rupture. Depending on the extent of the infraumbilical defect and the stage of development when rupture occurs, bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, or epispadias develops (Fig. 24.19). Jones reviewed the records of all female patients diagnosed with bladder exstrophy at Johns Hopkins Hospital over a 20-year time span. Of 18 patients with adequately described external genitalia, 13 had small, anteriorly displaced vaginal orifices, and the remaining five patients had vaginal orifices of normal size and location. In this series, only a third of patients with ECC demonstrated the defect of narrowing of the vagina.

FIGURE 24.15 A: Repeated operation on the vaginal outlet when the operation was not completed at the first procedure. B: The posterior incision. C: The vagina is exposed. D: The closure. |

Exstrophy-epispadias complex may be associated with a wide range of both genital and extragenital abnormalities. Stanton reviewed 70 patients with bladder exstrophy and observed an increased incidence of various müllerian anomalies. Eleven patients were observed to have associated rectal

prolapse. Blakely and Mills observed various extragenital abnormalities in their series, including rectal prolapse, imperforate anus, exophthalmos, renal agenesis, and spina bifida.

prolapse. Blakely and Mills observed various extragenital abnormalities in their series, including rectal prolapse, imperforate anus, exophthalmos, renal agenesis, and spina bifida.

Treatment

Our understanding of appropriate urologic management of bladder exstrophy has evolved greatly over the past few decades; improved management has markedly increased the life expectancy and quality of life of these patients. Historical methods of treatment involved bladder excision and a urinary diversion procedure such as ureterosigmoidostomy. These techniques were complicated by serious sequelae, including pyelonephritis, hyperchloremic acidosis, rectal incontinence, ureteral obstruction, and later development of malignancy. Modern care of the patient with complex pelvic congenital disorders mandates a multidisciplinary approach that includes gynecologic surgeons, urologists, neurologists, endocrinologists, pediatricians, and allied health professionals.

Urologic management of bladder exstrophy relies on a staged approach to functional bladder closure. The initial procedure consists of primary bladder closure with or without iliac osteotomies to aid closure of the pelvic ring and growth and improvement of bladder capacity. The second-stage procedures usually involve bladder neck reconstruction to improve continence and bilateral ureteral reimplantations to prevent reflux. Both failures and primary reconstruction have also been performed using continence urostomies, such as the Mainz II pouch. Mingin and coworkers and Gerharz and colleagues have reported their success using this technique.

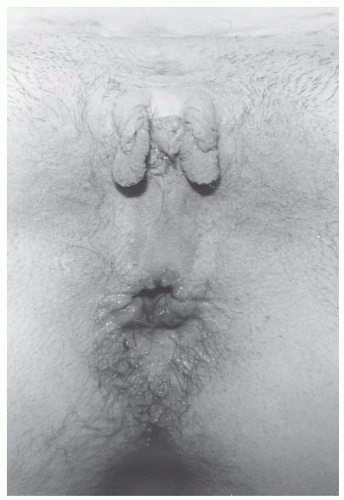

FIGURE 24.18 Preoperative photograph of a patient undergoing reconstruction of the external genitalia. Note the bifid clitoris and small anterior vaginal orifice. |

FIGURE 24.19 Anatomic features of (A) epispadias, (B) classic bladder exstrophy, and (C) cloacal exstrophy in females. |

Genital anomalies in ECC can usually be sufficiently corrected to allow for sexual activity and pregnancy. The adjunctive gynecologic procedures in ECC attempt to correct the

anterior displacement and narrowing of the vagina and the bifid separation of the clitoris.

anterior displacement and narrowing of the vagina and the bifid separation of the clitoris.

The surgical approach to the external genitalia in patients with ECC has evolved from that first described by Howard Jones Jr. in 1973. Particular emphasis is placed on attainment of an adequate vaginal diameter without further predisposing to subsequent prolapse. The first step is vertical incision into the posterior raphe of what resembles fused scrotolabial folds; next, Allis clamps are placed laterally for traction. Fine-needle point electrocautery is then used to further open the incision, with special care taken not to take this incision too far posteriorly. The lateral portions of the incision are secured with 3-0 nonreactive absorbable sutures for further traction. The posterior vaginal edges are undermined to allow their mobilization to the exterior. The vaginal mucosa is then approximated to the perineal surface with interrupted and figure-of-eight sutures, incorporating the superficial perineal muscles into the closure. In the more posterior portion of the closure, 2-0 nonreactive absorbable suture is used, because this is the area of greatest tension. At completion, there is a significant increase in the diameter of the vagina, and the vaginal orifice usually accommodates two fingers.

Experience with management of ambiguous genitalia has shown a decrease in the incidence of postoperative vaginal stenosis if dilatation therapy is employed during the constrictive phase (the first 6 weeks) of healing. For this reason, following reconstruction of the external genitalia and exteriorization of the vagina, appropriately sized Lucite dilators are used once or twice a day for this 6-week period or until healing is complete. Patients who undergo surgical correction in early infancy are at risk for vaginal stenosis as they age. In a series by Cerveillone, one third of patients corrected in infancy underwent vaginoplasty by age 15.

Reapproximation of the bifid clitoris (Fig. 24.20) is primarily cosmetic and may disrupt erogenous sensitivity. The technique involves excising a diamond-shaped area of skin and subcutaneous tissue between the clitoral bodies. The medial aspect of each side of the clitoris is then denuded and undermined to allow a central reapproximation with a side-to-side closure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree