Surgery for Benign Disease of the Ovary

Joseph S. Sanfilippo

John A. Rock

DEFINITIONS

Accessory ovary—An additional ovarian mass close to the normally placed ovary and connected to it by the utero-ovarian or infundibulopelvic ligament.

Fertility preservation prior to cancer therapy—Affording the patient prior to provision of chemoradiation therapy a host of options that provide for ovarian tissue, embryo, or oocyte cryopreservation as well as surgical procedures designed to protect the ovaries from radiation therapy.

Fimbria ovarica—The structure attaching the infundibulum of the fallopian tube to the distal pole of the ovary. It is vitally important to the fimbrial ovum capture mechanism.

Malpositioned ovary—An ovary located above the pelvic brim because of a lack of normal descent into the pelvis. It may be elongated, but it remains attached to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament and to the fallopian tube by the fimbria ovarica.

Ovarian cortex—The outer layer of the ovary consisting of an outer zone, which is mainly collagenous (tunica albuginea), and an inner zone, which is less fibrous and more cellular and contains the germ cells (primordial follicles).

Ovarian medulla—The inner region surrounding the hilum of the ovary. It contains no follicles, only blood vessels and the remnants of the tubular structures that are homologous to the male testis (rete testis).

Ovarian remnant—Persistent ovarian tissue unintentionally left behind following oophorectomy.

Prophylactic oophorectomy—In genetic mutation carriers, that is, BRCA1 or BRCA2, removal of both ovaries upon completion of childbearing in an effort to minimize chance of ovarian cancer.

Residual ovary—Symptomatic ovarian tissue following removal of the ovary.

Supernumerary ovary—An additional ovary that has no direct or ligamentous connection with a normally placed ovary. It is located at a distance from the normally placed ovaries.

Tumor markers—Substances identified in higher than normal amounts in blood, urine, or body tissues of patients with specific malignancies. They are produced directly by the tumor or as a response to the presence of cancer, that is, indirect marker.

Tunica albuginea—Condensed ovarian stroma that forms a fibrous capsule.

Evaluation and management of benign disease of the ovary continues to unfold with new and challenging clinical alternatives. Progress has occurred with regard to understanding the genetics of ovarian function, new surgical approaches to ovarian disease, and a host of knowledge that clinicians should be aware of. The population is living longer, and cancer survivors are increasing exponentially. All of this leads us to focus on enhancing our understanding of preservation of ovarian function; expanding the potential for conception, which includes determining treatment related to decreased postoperative adhesion formation; and addressing an array of other aspects related to ovarian activity.

It has been established that the ovaries and fallopian tubes are sensitive to ischemia from surgical trauma; adhesions may develop as a result; the normal anatomic relationship between fallopian tubes, ovaries, and uterus may be altered. Knowledge regarding anatomy and embryology of the ovaries and other reproductive organs complemented by mastery of the principles of microsurgery that can be applied to virtually any surgical procedure are the prerequisites for excellent results following ovarian reconstructive surgery. Embryology and anatomy are addressed in this chapter with emphasis on the importance of the anatomic relationship of the ovary to other pelvic organs in the section on the evaluation and management of an adnexal mass. State-of-the-art surgical procedures—both via minimally invasive, robotic-assisted and laparotomic approaches and techniques devised for the reconstruction of the ovary—for restoration of normal pelvic anatomy are presented in the context of specific pathology or other abnormal conditions that require surgical intervention. This chapter also focuses on pediatric and adolescent gynecologic surgical procedures that are performed when ovarian pathology is identified.

EMBRYOLOGY

The reproductive system is derived from mesoderm. The primordium of the urogenital ridge is divided into two segments. One is the nephrogenic ridge, that is, metanephros derivatives, the renal system; the other is the gonadal ridge for development of the reproductive tract. Gonads are a reflection of three origins: mesothelium, mesenchyme, and primordial germ cells. The paramesonephros gives rise to the fallopian tubes and the uterus. Two gonadal ridges arise early in gestation (4 to 5 weeks) in the

developing embryo as thickening on the medial aspect of the coelomic cavity adjacent to the mesonephros. These gonadal outgrowths are composed of coelomic epithelium and underlying mesenchyme projecting into the future peritoneal cavity. The epithelial and mesenchymal cells of the gonadal primordia are of mesodermal origin (large, spherical ovoid germ cells that originate extragonadally in the wall of the yolk sac and migrate to the developing gonads). Until the 6th week of gestation, the gonads of the two sexes remain morphologically indistinguishable. The presumptive ovaries remain undifferentiated until the onset of meiosis at the end of the first trimester. The ovarian cortex is a single germinal epithelium. The tunica albuginea lies beneath the cortex and is composed of connective tissue. The stroma is composed of fibroblasts, smooth muscle, endothelium, and interstitial cells, including undifferentiated theca cells and corpora albicans.

developing embryo as thickening on the medial aspect of the coelomic cavity adjacent to the mesonephros. These gonadal outgrowths are composed of coelomic epithelium and underlying mesenchyme projecting into the future peritoneal cavity. The epithelial and mesenchymal cells of the gonadal primordia are of mesodermal origin (large, spherical ovoid germ cells that originate extragonadally in the wall of the yolk sac and migrate to the developing gonads). Until the 6th week of gestation, the gonads of the two sexes remain morphologically indistinguishable. The presumptive ovaries remain undifferentiated until the onset of meiosis at the end of the first trimester. The ovarian cortex is a single germinal epithelium. The tunica albuginea lies beneath the cortex and is composed of connective tissue. The stroma is composed of fibroblasts, smooth muscle, endothelium, and interstitial cells, including undifferentiated theca cells and corpora albicans.

Sexual differentiation requires initiation by various genes, along with a single gene determinant on the Y chromosome (testis-determining factor), which is necessary for testicular differentiation. In XX individuals (in the absence of a Y chromosome), the bipotential gonad develops into an ovary.

The mechanisms responsible for gonadal sex differentiation are largely unknown. Investigators have theorized the presence of a testis-determining factor (H-Y cell-surface antigen on the short arm of the Y chromosome) that is elaborated by a specific gene. Meiosis-inducing and meiosis-preventing substances, both of which are produced by cells derived from mesonephric structures adjacent to the gonad, are the agents of regulation of ovarian and testicular germ-cell differentiation. The balance between these two substances varies between the two sexes and at different stages of development. The meiosisinducing substance predominates in the fetal ovary. Maternal ovarian hormone production is not required for differentiation of the germ cells or, apparently, for later development of the fetal reproductive tract. Various ultrastructural studies have shown no specific changes in fetal granulosa cells that can be definitely associated with steroid hormone secretion such as is identified in the fetal Leydig cells. Thecal cells play an essential role in steroid synthesis in the adult ovary, but they do not appear until later in gestation and even then retain a relatively undifferentiated appearance. Fetal pituitary gonadotropin production begins as early as 10 weeks gestation and reaches peak levels at midgestation. Gonadotropins have a major influence on follicular development in the adult ovary, but evidence for a similar function in the fetus is lacking.

GENE EXPRESSION

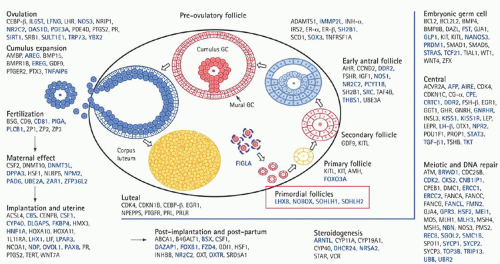

Understanding of the genetics of the ovary continues to evolve. With the advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR, fluorescence in situ hybridization, single nucleotide polymorphism, and a host of other genetic advances, understanding of ovarian function has reached a new level (Fig. 28.1). Table 28.1 provides information regarding genes and associated phenotype.

Genes often are associated with specific clinical problems, for example, Kallmann syndrome, a genetic condition that results in the failure of pubertal development. Hypogonadism associated with a total lack of sense of smell (anosmia) or a heavily reduced sense of smell (hyposmia) characterizes the syndrome. Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is characterized by hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, which equates with the loss of ovarian function before age 40. The problem of POI overall is associated with a host of gene defects, all of which set the stage for genetic testing in patients in the reproductive age group with amenorrhea in association with hypergonadotropic state. Genes are also involved with cumulus expansion (GDF9 and BMP15) and endometriosis, and most recently serve as predictors of oocyte quality and successful embryo implantation and development. Specific follicular cell receptors bind growth factors, which are locally synthesized with the ultimate effect of intracellular signaling and protein kinase activation. This activity affects transcription of targeted genes. Gene expression is involved in follicle development, ovulation,

and corpus luteum and corpus albicans formation. Transcription factors include protooncogenes, c-Myc, and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein.

and corpus luteum and corpus albicans formation. Transcription factors include protooncogenes, c-Myc, and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein.

TABLE 28.1 Gene Mutations and Ovarian Activity | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FEMALE FETAL DEVELOPMENT

The ovarian surface cortex, during the early prefollicular stage, is characterized by germ cells and granulosa cells organized in cords and sheets, but the cortex lacks specific conformation. The final distinctive change to occur in the fetal ovary is the onset of meiosis at the 11th or 12th week of gestation. Meiosis is preceded by differentiation of primitive germ cells into actively dividing mitotic cells called oogonia. The mitotic divisions of the oogonia are associated with complete separation at telophase, leaving the daughter cells connected by intracellular bridges. After a series of mitotic divisions, there is progressive entry of cells into meiosis, beginning in the innermost cortex and gradually extending to the periphery. These cells passing through the various stages of the first meiotic prophase are then designated oocytes. By late gestation, all surviving oocytes have advanced to the diplotene stage. Further differentiation of the oocytes is arrested at this stage and does not resume until ovulation begins at menarche, approximately 12 years later.

Follicular formation begins at 18 to 20 weeks gestation and continues throughout the remaining weeks of fetal development. All the surviving oocytes are surrounded by adjacent granulosa cells; oocyte and follicular growth are well established by the late fetal and early neonatal period. The constant degeneration and loss of oocytes before their incorporation into the follicles reduces their numbers to only 1 to 2 million (follicles) in the newborn ovary.

ANATOMY

The dimensions of the adult ovary vary from individual to individual but average 3 to 5 cm in length, 2 to 3 cm in width, and 1 to 2 cm in diameter, with a weight of 3 to 8 g. The ovarian capsule is smooth in childhood, but its surface becomes pitted from follicular maturation and atresia.

The size, shape, and position of the ovary in the pelvis are somewhat variable, and both the consistency and the follicular changes taking place within the ovary vary with stage of the menstrual cycle. The ovary typically is anchored to the sidewall of the pelvis in the shallow peritoneal fossa of Waldeyer formed between the angles of proximity of the ovary to the ureter. This knowledge is important before dissecting the ovary off the pelvic sidewall.

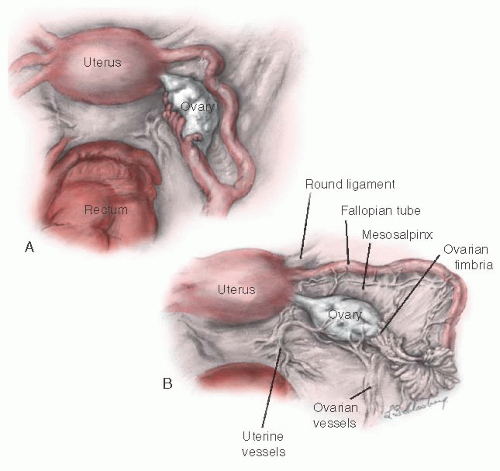

The ovary is connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament, to the posterior aspect of the broad ligament by the mesovarium ligament, and to the lateral pelvic sidewall by the infundibulopelvic ligament (Fig. 28.2). The

mesovarium ligament attaches to the mesentery of the ovary. The other two ligaments are attached at the hilum of the ovary.

mesovarium ligament attaches to the mesentery of the ovary. The other two ligaments are attached at the hilum of the ovary.

The ovary migrates downward from high in the abdomen during embryonic life. The infundibulum of the fallopian tube extends onto the ovary and is attached to it at its most distal pole by the fimbria ovarica. The relation of the ovary to the fimbria ovarica and to the utero-ovarian ligament is crucial, and they should be carefully maintained during ovarian reconstruction.

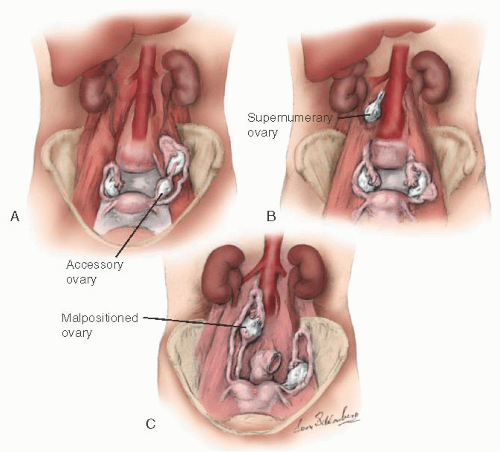

During embryogenesis, the ovary may assume an unusual appearance (i.e., it may be septate) or assume an unusual position (Fig. 28.3). An accessory ovary (Fig. 28.3A) usually is close to or is connected to a normally placed ovary. An accessory ovary also may be attached to the broad, utero-ovarian, or infundibulopelvic ligaments. Unlike the accessory ovary, a supernumerary ovary (Fig. 28.3B) must have an independent embryologic origin. It may develop from a primordium such as arrested migrating gonadocytes. A supernumerary ovary consists of typical ovarian tissue but has no direct or ligamentous connection with a normally placed ovary. A supernumerary ovary is thus a true third ovary that has independent function and is located at a point that is distant to a normally placed ovary. Ovarian malposition (Fig. 28.3C) also may occur when the ovary fails to descend into the pelvis to assume its normal location. In ovarian malposition, the ovary is attached as it should be to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament and to the fallopian tube by the fimbria ovarica, but it may lie adjacent to the liver or spleen. The ovary is elongated and may measure up to 15 cm in length. The fallopian tube attaching to such a malpositioned ovary may be 20 to 26 cm in length, almost twice its normal length.

The normal ovary has a surface covering composed of a single layer of flattened, germinal epithelial cells. This layer is contiguous at the ovarian hilum, with the peritoneal epithelium of the posterior leaf of the broad ligament. Beneath the germinal epithelium is a second layer of condensed ovarian stroma that forms a fibrous capsule, the tunica albuginea. The area through which the vessels and nerves enter and exit is the hilum of the ovary. Immediately around the hilum and extending into the substance of the ovary is an area known as the medulla, which is covered by the cortex. The medulla is composed of fibrous tissue unlike the condensed stroma of the ovarian cortex. The medulla contains no follicles; it has only blood vessels and the remnants of the tubular structure that would have developed into a testis (i.e., the rete ovarii) had the fetus been male.

The ovarian artery arises from the renal arteries. The artery descends from the aorta and crosses the ureter obliquely to enter the infundibulopelvic ligament on its course to the ovary. When it reaches the broad ligament, the ovarian artery branches to supply the fallopian tube and ovary before it finally anastomoses directly with the uterine artery to form a continuous arcade in the broad ligament. The ovarian veins are situated mainly in the mesosalpinx, where they give rise to the pampiniform plexus. At the outer end of the broad ligament, this plexus coalesces to form a single, large ovarian vein. The ovarian vein runs adjacent to ovarian artery to terminate in the inferior vena cava on the right and the renal vein on the left.

The lymphatic vessels of the ovary drain in three directions. The main group accompanies the ovarian vessels in the infundibulopelvic ligament and eventually reaches the periaortic nodes in the vicinity of the kidney. Other lymphatic channels communicate with channels of the opposite ovary by crossing the fundus of the uterus through the ovarian ligament. Some channels drain through the ovarian and round ligaments into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes in the groin. The ovary is supplied by both motor and sensory parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves,

which accompany the ovarian vessels from the abdomen as they pass into the infundibulopelvic ligament to reach the hilum of the ovary. The segmented nerves supply the ovary from T10 and T11.

which accompany the ovarian vessels from the abdomen as they pass into the infundibulopelvic ligament to reach the hilum of the ovary. The segmented nerves supply the ovary from T10 and T11.

ADNEXAL MASS

The uterine adnexa (gynecologic origin) consist of the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, and the uterine ligaments. Although adnexal pathology often involves one of these structures, contiguous tissue of nongynecologic origin also may be involved. Adjunctive diagnostic techniques such as sonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) may help delineate the nature of adnexal enlargement. Pelvic ultrasonography, especially three dimensional, is an accurate means of determining the location, size, extent, and consistency of pelvic masses and is also useful for detecting obstructive uropathy, ascites, and metastasis. Other more specialized diagnostic procedures also may be necessary for the evaluation of an adnexal mass (Table 28.1).

Computed tomography scanning has been particularly useful in gynecologic oncology because it helps define the extent of paracervical and parametrial involvement and allows a reasonable determination of the resectability of malignant neoplasms. Magnetic resonance imaging has surpassed CT in the precision of measurement of adnexal masses. Magnetic resonance imaging also allows a clear definition of the relationship of adjacent organs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree