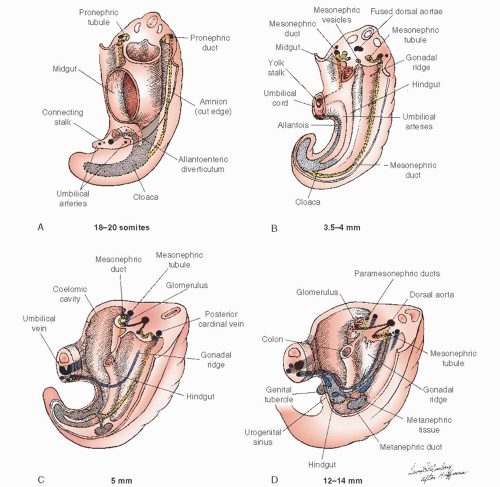

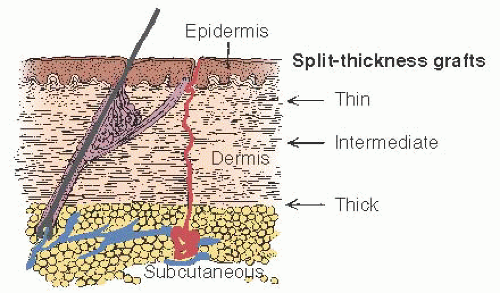

TAKING THE GRAFT

After a careful pelvic examination is performed under anesthesia to verify previous findings, the patient is positioned for taking a skin graft from the buttocks. For cosmetic reasons, the graft should not be taken from the thigh or hip unless for some reason it cannot be obtained from the buttocks. Patients may be asked to sunbathe in a bathing suit before coming to the hospital so that its outline can be seen; an attempt should be made to take the graft from both buttocks within these borders. The quality of the graft determines to a great extent the success of the operation. We have found the Padgett electrodermatome to be the most satisfactory instrument for taking the graft. With relatively little experience and practice, the gynecologic surgeon can successfully cut a graft of controlled width and thickness (

Fig. 25.6). The instrument is set and checked for taking a graft approximately 0.018 inch thick and 8 to 9 cm wide. The total graft length should be 16 to 20 cm. If the entire graft cannot be taken from one buttock, then a graft 8 to 10 cm long is needed from each buttock.

The skin of the donor site is prepared with an antiseptic solution (povidone-iodine), which is then thoroughly washed away. The skin is then lubricated with mineral oil as assistants steady and stretch the skin tight. Considerable pressure should be applied uniformly across the dermatome blade. The thickness of the graft must have minimal variation. A graft that is a little too thick is better than one that is a little too thin. There should be no breaks in the continuity of the graft. The graft is placed between two layers of moist gauze, and the donor sites are dressed. The donor site is soaked with a dilute solution of epinephrine for hemostasis, and a sterile dressing is applied. A pressure dressing is then placed over the site; this dressing can be removed on the seventh postoperative day. The sterile dressing dries in place over the donor site and ultimately will fall off by itself. Moistened areas on the dressing can be dried with cool air. If there is separation and evidence of some superficial infection, then merbromin can be applied to these areas.

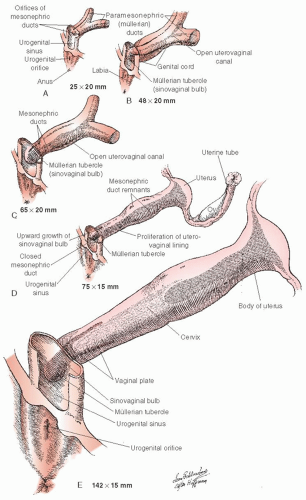

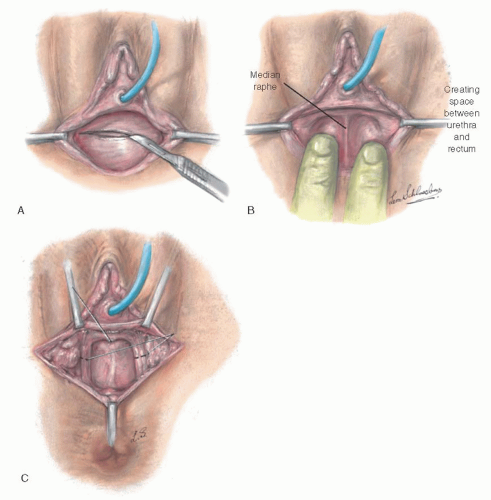

CREATING THE NEOVAGINAL SPACE

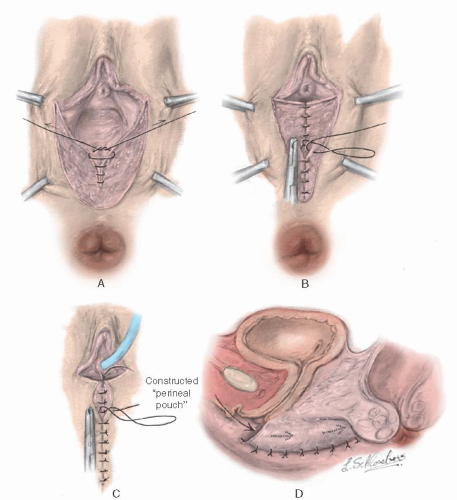

The patient is placed in the lithotomy position, and a transverse incision is made through the mucosa of the vaginal vestibule (

Fig. 25.7A). The space between the urethra and bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly is dissected until the undersurface of the peritoneum is reached.

This step may be safer with a catheter in the urethra and sometimes a finger in the rectum to guide the dissection in the proper plane. After incising the mucosa of the vaginal vestibule transversely, the physician often is able to create a channel on each side of a median raphe (

Fig. 25.7B), starting with blunt dissection and then dilating each channel with Hegar dilators or with finger dissection. In some instances, it may be necessary to develop the neovaginal space by dissecting laterally and bringing the fingers toward the midline. The median raphe is then divided, thus joining the two channels. This maneuver is helpful in dissecting an adequate space without causing injury to surrounding structures.

To avoid subsequent narrowing of the vagina at the level of the urogenital diaphragm, it may be helpful to incise the margin of the puborectalis muscles bilaterally along the midportion of the medial margin (

Fig. 25.7C). Although useful in all circumstances, incision of the puborectalis muscle is more important in cases of androgen insensitivity syndrome with android pelvis, in which the levator muscles are more taut against the pelvic diaphragm, than in cases of gynecoid pelvis. Incision of the puborectalis muscle causes no difficulty with fecal incontinence, significantly improves the ease with which the vaginal form can be inserted into the canal in the postoperative period, and has eliminated the problem of contracture of the upper vagina caused by a poorly applied form. The dissection should be carried as high as possible without entering the peritoneal cavity and without cleaning away all tissue beneath the peritoneum. A split-thickness skin graft will not take well when applied against a base of thin peritoneum. All bleeders should be ligated by clamping and tying them with very fine sutures. It is essential that the vaginal cavity be dry to prevent bleeding beneath the graft. Bleeding causes the graft to separate from its bed, resulting in the inevitable failure of the graft to implant in that area and in local graft necrosis.

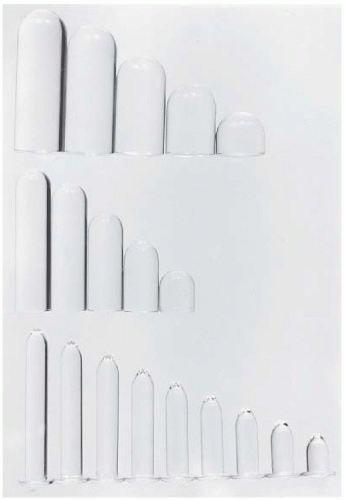

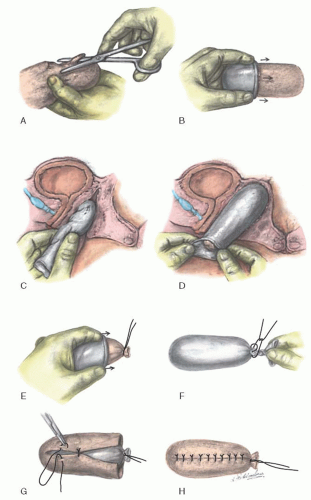

PREPARING THE VAGINAL FORM

Early skin grafts were formed over balsa, which has the advantages of being an inexpensive, easily available, light wood that can be sterilized without difficulty. It also can be whittled easily in the operating room to a proper shape to fit the new vaginal space. However, uneven pressure from the form can cause a skin graft to slough in places, and pressure spots are associated with an increased risk of fistula formation. The Counseller-Flor modification of the McIndoe technique (

Fig. 25.8) uses, instead of the rigid balsa form, a foam rubber mold shaped for the vaginal cavity from a foam rubber block and covered with a condom. The foam rubber is gas sterilized in blocks measuring approximately 10 × 10 × 20 cm. The block is shaped with scissors to approximately twice the desired size, compressed into a condom, and placed into the neovagina (

Fig. 25.8A-C). The form is left in place for 20 to 30 seconds with the condom open to allow the foam rubber to expand and conform to the neovaginal space (

Fig. 25.8D). The condom is then closed, and the form is withdrawn. The external end is tied with 2-0 silk, and an additional condom is placed over the form and tied securely (

Fig. 25.8E, F).

SEWING THE GRAFT OVER THE VAGINAL FORM

The skin graft is then placed over the form and its undersurface exteriorized and sewn over the form with interrupted vertical mattress 5-0 nonreactive sutures (

Fig. 25.8G, H). Where the graft is approximated, the undersurfaces of the sutured edges are also exteriorized.

The graft should not be “meshed” to make it stretch farther, and the edges of the graft should be approximated meticulously around the form without gaps. Granulation tissue develops at any place where the form is not covered with skin. Contraction usually occurs where granulation tissue forms. After the form has been placed in the neovaginal space, the edges of the graft are sutured to the skin edge with 5-0 nonreactive absorbable sutures, with sufficient space left between sutures for drainage to occur. The physician must be careful not to have the form so large that it causes undue pressure on the urethra or rectum. A balsa form should have a groove to accommodate the urethra. With a foam rubber form, this is unnecessary. A suprapubic silicone catheter is placed in the bladder for drainage. If the labia are of sufficient length, then the form can be held in place by suturing the labia together with two or three nonreactive sutures.

REPLACING WITH A NEW FORM

After 7 to 10 days, the form is removed and the vaginal cavity is irrigated with warm saline solution and inspected. This is usually performed with mild sedation and without an anesthetic. The cavity should be inspected carefully to determine whether the graft has taken satisfactorily in all areas of the new vagina. Any undue pressure by the form should be noted and corrected. It is especially important that there not be too much pressure superiorly against the peritoneum of the cul-de-sac. Such a constant upward pressure could result in weakness with subsequent enterocele formation. The new vaginal cavity must be inspected frequently to detect and to prevent pressure necrosis of the skin graft.

The patient is given instructions on daily removal and reinsertion of the form and is taught how to administer a lowpressure douche of clear warm water. She is advised to remove the form at the time of urination and defecation, but otherwise to wear it continuously for 6 weeks. A neoprene form, which is much easier to remove and keep clean than a foam rubber form, is substituted for the original form in 6 weeks. A new form is molded with a sterile sheath cover (condom) to fit the size of the vaginal canal. The patient is instructed to use the form during the night for the following 12 months. If there has been no change in the caliber of the vagina by that time, then it is unlikely to occur later, and insertion of the form at night can be done intermittently until coitus is a frequent occurrence. However, if there is the slightest difficulty in inserting the form, then the patient should be advised to use the form continuously again. Most patients are able to maintain the form in place simply by wearing tighter underclothes and a perineal pad. Douches are advisable during residual vaginal healing and discharge.

RESULTS AND COMPLICATIONS

Results with the McIndoe operation have improved over the years. Recently, reported percentages of satisfactory results have ranged from 80% to 100%. The serious complications formerly associated with the McIndoe operation have been significantly reduced by improvements in technique and greater experience. Serious complications do still occur, however, including a 4% postoperative fistula rate (urethrovaginal, vesicovaginal, and rectovaginal), postoperative infection, and intraoperative and postoperative hemorrhage. Failure of graft take is also still reported as an occasional complication. Failure of graft take often leads to the development of granulation tissue, which might require reoperation, curettage of the granulation tissue down to a healthy base, and even regrafting. Minor granulation can be treated with silver nitrate application. The functional result is more important than the anatomic result in evaluating the success of this operation. Although a vagina of only 4 cm is adequate for some couples, in most instances, a vagina smaller than 4 cm causes major problems.

The postoperative results have improved significantly since the balsa vaginal form was replaced by the foam rubber form. Between 1950 and 1989, the McIndoe operation was performed on 94 patients at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. During these 39 years, 83% of the 94 patients had a 100% take of the graft; in only three cases was there a significant area over which the graft failed.

Urethrovaginal fistula has become even more infrequent since the introduction of the suprapubic catheter and the foam rubber form. The catheter is removed when the patient is voiding well and has no residual urine. In general, the patient is able to void without difficulty within the first few days of the procedure. Prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics started within 12 hours of surgery and continued for 7 days are of definite value in reducing the incidence of graft failures from infection in the operative site.

Because of the excellent results obtained after a modified McIndoe vaginoplasty, this operation is recommended as the procedure of choice for women unable or unwilling to obtain a neovagina with dilatation methods. Women with a flat perineum with no dimple or pouch have no alternative other than the McIndoe vaginoplasty to obtain a neovagina for comfortable sexual relations.

Desirability of the modified McIndoe procedure may be increased by the use of alternative graft harvest sites to conceal possible aesthetic concerns of the buttock site, as proposed by

Höckel and colleagues. The authors proposed the use of split skin harvesting from the scalp because thin (0.25-mm) split skin grafts do not seem to hamper hair growth at the donor site nor lead to hair growth at the recipient site. Because alopecia has been reported as a complication associated with technical errors, more experience is necessary before advocating the scalp as a potential graft harvest site.

It is important that a McIndoe operation be performed correctly the first time. If the vagina becomes constricted because of granulation tissue formation, injury to adjacent structures, or failure to use the form properly, then subsequent attempts to create a satisfactory vagina are more difficult. The first operation has the best chance of success.

Ozek, like many other surgeons, modified the McIndoe procedure by describing an X-type perineal incision and the use of a perforated vaginal mold during the postoperative period. He postulated that this incision minimized stricture at the vaginal introitus and provided greater ease of dissection of the vaginal cavity. He reinforced that the overall procedure is simple with a generally uneventful postoperative course. Complications included infection, failure of skin graft take, stress urinary incontinence, partial graft loss, and vaginal stricture. All were treated satisfactorily except the patient with stress urinary incontinence.

Despite any minor modifications of the McIndoe vaginoplasty, the essential components of dissection of an adequate space, split-thickness skin grafting, and continuous dilatation during the contractile phase of healing remain unchanged. Recent reviews continue to support the safety and efficacy of the procedure. Hojsgaard and Villadsen reported 26 patients who underwent vaginoplasty, 18 of whom had Rokitansky syndrome. All patients were recorded as having a satisfactory result with complete graft take, adequate vaginal dimensions, and no strictures or fistulas giving symptoms. Complete take was achieved in 33% of patients within a week postoperatively, and after one further grafting procedure, an additional 38% had complete take. The intraoperative and early postoperative complications were perforation of the rectum in one patient (3.8%) and postoperative bleeding in three patients (11.5%). The late complications were vaginal stricture in three patients (11.5%), urethrovaginal fistula in two patients (7.7%), and rectovaginal fistula in one patient (3.8%). Alessandrescu and colleagues described the surgical management of 201 cases of Rokitansky syndrome. The surgeon substituted a modified transverse perineal incision and a perforated, rigid plastic mold. Intraoperative and postoperative complications consisted of two rectal perforations (1%), eight graft infections (4%), and 11 infections of graft site origin (5.5%). Sexual satisfaction was investigated with both objective and subjective criteria. Among the 201 cases, 83.6% had anatomic results evaluated as “good,” 10% as “satisfactory,” and 6.5% as “unsatisfactory.” More than 71% of patients rated their sexual life as “good” or “satisfactory” and reported that they had been able to experience orgasms related to vaginal intercourse. Twenty-three percent reported the ability to have sexual intercourse but had no ability to achieve orgasm, and only 5% expressed dissatisfaction with their sexual performance. Strickland and colleagues reported on the coital satisfaction, perception of vaginal competence, and impact on lifestyle of adult women undergoing vaginoplasty as adolescents. Ten of twenty-two women responded to a questionnaire at a median of 18 years (range 5 to 13 years) following surgical intervention with a McIndoe vaginoplasty. All of the women had sexual experience, and 80% were sexually active at the time of evaluation. The most frequent difficulty reported was vaginal dryness and lack of lubrication with sexual intercourse. Ninety percent of the subjects expressed satisfaction that sexual ability was acceptable. This experience also supports the role of the McIndoe vaginoplasty in providing young women with vaginal agenesis long-term coital ability and minimal disabilities.

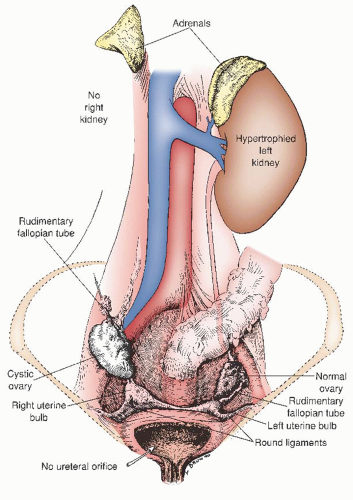

DEVELOPMENT OF COMPLICATIONS

Several case reports exist of malignant disease developing in a vagina created by various techniques; these reports were reviewed by Gallup and colleagues, as well as others. The authors reported a patient who was initially treated for intraepithelial malignancy by total vaginectomy combined with a split-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty to reconstruct a functional vagina. The authors noted a lesion in her vaginal apex 7 years later. These findings suggest that epithelium transplanted to the vagina can assume the oncogenic potential of the lower reproductive tract. The evidence supports a risk of neoplastic change in both skin and bowel grafts, with a reported average interval from vaginoplasty to diagnosis on the order of 19 years or greater. Epithelium transplanted to the vagina will assume the oncogenic potential of the lower reproductive tract. With less than 25 cases of primary carcinoma of the neovagina reported, it is presently unclear if transplantation of bowel or other graft tissue alone changes the malignancy risk. Consideration of a plan for surveillance and counseling regarding transmission risk for virally related dysplastic change in the lower genital tract is also extremely important for any patients undergoing neovaginoplasty. Neovaginal vault prolapse has also been reported in patients managed both medically and surgically. Without apical or lateral suspension by endopelvic fascial attachments, subsequent prolapse may develop with any type of neovagina. Prolapse in neovaginal segments created by dilation, McIndoe technique, skin flaps, and bowel segments is reported. Abdominal suspension via sacrocolpopexy, abdominal suspension to the Cooper ligament, vaginal resection of redundant prolapsed bowel neovagina, and sacrospinous ligament suspension have all been described as treatment. Kondo and colleagues report a recurrence rate after surgical treatment of 25%.