More than 200 procedures have been described in the literature for the treatment of stress incontinence. This reflects a combination of the evolution of established and effective procedures as well as the introduction of newer technologies and materials. Most of these surgeries, including the anterior colporraphy with Kelly placation and Pereyra needle suspensions, are now of historical interest only. This chapter focuses on retropubic and transobturator midurethral sling procedures, which have become the mainstays of surgical therapy for SUI. Other options, appropriate for selected populations, include the retropubic urethropexy, rectus fascia suburethral sling procedures, and the injection of bulking agents. These also are addressed.

Retropubic Midurethral Sling Procedures

The retropubic midurethral sling was first described by Ulmsten and colleagues. The appeal of a tension-free midurethral sling is that it is an effective, minimally invasive technique that can be applied to a day-surgery setting. Thus, this approach was an important innovation when it was introduced in the 1990s.

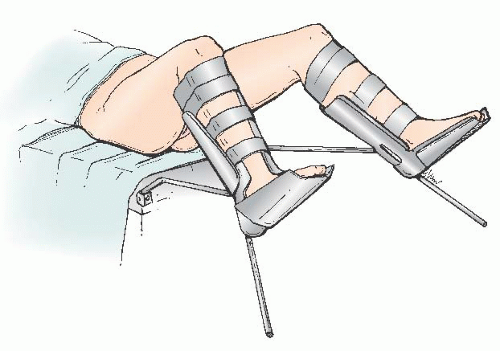

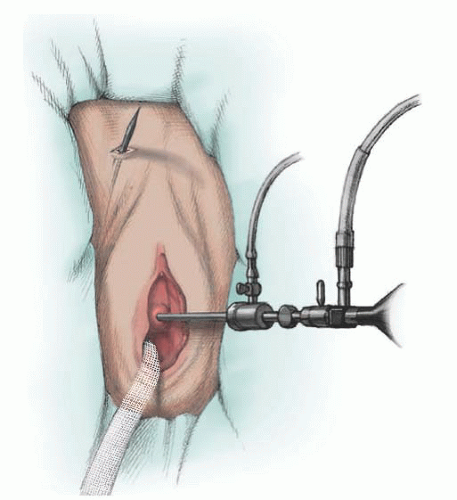

The patient is typically positioned in low lithotomy, with Allen stirrups (

Fig. 41.3). The bladder is emptied with an 18-F catheter. Suprapubic sites are marked approximately 2 to 3 cm lateral to the midline. These sites are selected to be medial to the pubic tubercle; they represent the lateral boundary for safe perforation of the abdominal wall. More lateral sling placement will increase the risk of neurovascular injury.

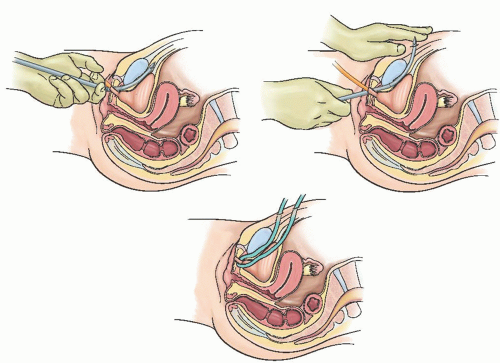

A 1- to 2-cm incision is made under the midurethra (

Fig. 41.4A). Typically, the distal aspect of the incision is 1 to 1.5 cm from the urethral meatus. The midurethral location can be confirmed via palpation of the Foley bulb while gentle traction is placed on the Foley. After the creation of the incision, a 2-cm tunnel is made with Metzenbaum scissors at a 45-degree angle toward the descending pubic ramus on each side (

Fig. 41.4B). Minimal vaginal dissection is recommended to limit bleeding from the paraurethral vascular plexus, to maintain the sling in its position under the midurethra (e.g., minimizing the probability that it will be displaced to the proximal or distal urethra), and to minimize the risk of mesh exposure.

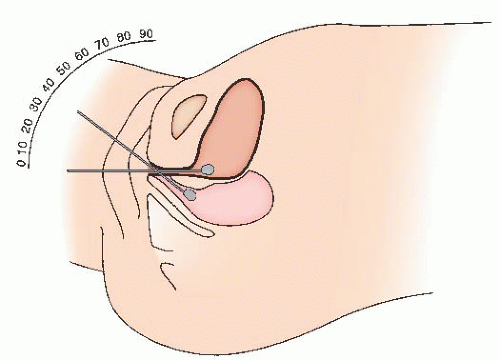

Some surgeons inject the vaginal wall and retropubic space with a dilute solution of local anesthetic (such as a 3:1 dilution of 1% xylocaine or ¼% bupivacaine). A spinal needle is advanced through the abdominal wall, immediately along the pubis, and into the retropubic space. Traditionally, 5 to 10 mL of solution is injected suprapubically on each side. Then, 10 mL

of the solution is placed in the retropubic space bilaterally by a vaginal approach. The needle is advanced through the vaginal incision and under the vaginal epithelium, injecting small amounts along the intended path of the sling trocar, entering the retropubic space at the junction of the descending pubic ramus and the pubis. Five to ten milliliters is placed on each side. Injection of saline or local anesthetic into the retropubic space (“hydrodissection”) is thought to distend the space, facilitating safe placement of the trocars. Some experts prefer injections of saline (for hydrodissection of the retropubic space) rather than a local anesthetic. This is because the benefits of local anesthetic injection are limited to the first few hours after surgery.

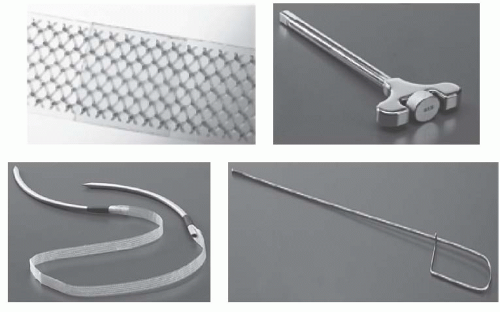

Commercially available midurethral slings consist of a polypropylene strap and rigid trocars for insertion (

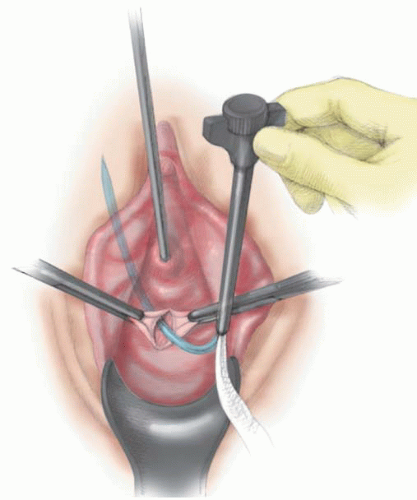

Fig. 41.5). Prior to placement of the trocar, a rigid catheter guide is placed through the 18-F catheter. Using the rigid guide, the bladder can be directed away from the side on which the surgeon is working, so as to minimize the risk of bladder injury. The retropubic sling is passed into the retropubic space using the curved trocar (

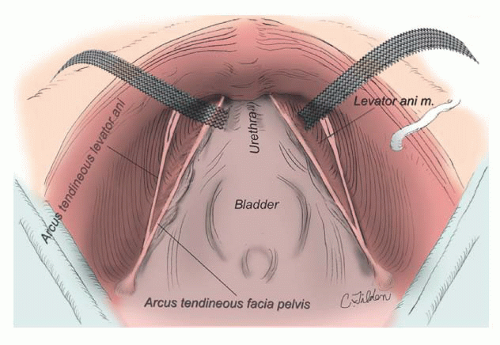

Fig. 41.6). A knowledge of retropubic anatomy is critical to the safe placement of the sling. The trocar should be advanced into the retropubic space at the junction of the descending pubic ramus and the pubis, immediately along the inferior surface of the bone. This is a relatively avascular zone of the retropubic space (

Fig. 41.7). If the trocar perforates in this location, the trocar will be lateral to the retropubic branches of the internal pudendal vessels and medial to the inferior epigastric, obturator, and accessory obturator vessels. If the trocar is directed away from the surface of the bone, a bladder perforation is more likely, as is an injury to branches of the perivesical venous plexus and vesical vessels. The pubic veins, branches of the obturator vessels that course medially along the ventral surface of the pubis, are the only vessels likely to be along the path of the needle placed in this fashion. After initial insertion through vaginal wall, the trocar may also pass close to (or through) the paraurethral vascular plexus, which arise from the internal pudendal and superior vesical arteries. Shobeiri found that injury to these paraurethral vessels is likely, but the related bleeding is of limited clinical significance and can typically be controlled by pressure or vaginal packing. He recommended minimal vaginal dissection to reduce risk of significant bleeding from the paraurethral vessels.

As the trocar is passed into the retropubic space, it hugs the pubic ramus as the endopelvic fascia is penetrated and then is advanced until the tip appears suprapubically, immediately

medial to the site previously marked (

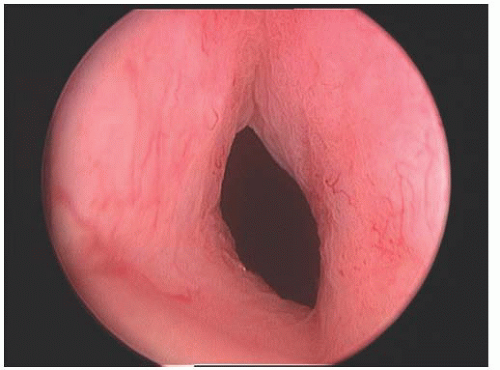

Fig. 41.8). The needle tip is passed just through the skin. The tape is passed on the opposite side using a similar technique. Cystoscopy is performed after each pass or, alternatively, after both passes have been made (

Fig. 41.9). If there is no bladder perforation, the needles are advanced and pulled completely through the abdominal wall. The needles are detached from the sling device. The sling with protective sheath is tightened over a number 9/10 Hegar dilator or other instrument, which is held in place until the sling is secured. The plastic sheaths are pulled free from the mesh, and excess sling material is cut flush to the skin surface. At this point, the Hegar dilator can be removed. The vaginal and skin incisions are closed. The sling is not sutured to any underlying tissue, and the composition of the mesh allows tissue ingrowth to fix the sling in place.

Anatomic studies have identified several techniques that minimize the risk to obturator and iliac vessels. For example, during passage of the retropubic trocars, the surgeon should not laterally divert the tip of the trocar; rotation of the trocar is a safer technique. Shobeiri demonstrated that if the surgeon rotates the needle without lateral diversion, injury to the external iliac vessels cannot except in cases of extreme rotation (>75 degrees). Injury may be increased if the trocar is both laterally diverted and rotated. The surgeon should also be familiar with the corona mortis, an anastomosis between the obturator and inferior epigastric vessels. This anastomosis is typically greater than 6 cm lateral to the midline and is reliably 3 cm lateral to the midline. Experienced retropubic surgeons are aware that this anastomosis is almost invariably present in a fat pad at the lateral aspect of Cooper ligament. Injury to the corona mortis can easily be avoided if the trocar does not pass more than 3 cm lateral to the midline. Finally, Rahn and colleagues have shown that perforation of the pubococcygeus muscle can occur if the retropubic trocar is deviated laterally (

Fig. 41.10), although perforation of the muscle is of uncertain consequence.

A vaginal pack is not usually placed unless there has been considerable bleeding. A Foley catheter is placed, or, alternatively, the patient may go to recovery without a catheter. A voiding trial is initiated in the recovery room; if the patient cannot void adequately, she performs self-catheterization, or a Foley catheter is placed. In the first week after surgery, voiding dysfunction is common. Patients discharged with an indwelling Foley catheter are scheduled to return to clinic for assessment of voiding function. About half of patients will void adequately by the time of discharge from day surgery. Of those who require catheterization, many are voiding well by the following day, and almost all have recovered normal voiding function within the first week.

The success rate of the retropubic midurethral sling is approximately 85%. Risk factors for failure include prior incontinence surgery, coexistent urge incontinence, and the absence of preoperative urethral hypermobility. Age also appears to be a risk factor for persistent SUI symptoms. Urodynamic parameters, such as low maximum urethral closure pressure and leak point pressure, may reduce objective success of midurethral slings; however, the predictive value of these parameters is relatively poor.

The most serious complications from the retropubic midurethral sling procedure pertain to the percutaneous passage of the trocar (

Table 41.2). There have been rare deaths from undiagnosed bowel perforation. Major vascular injury is rare and will be minimized by ensuring that the insertion needle does not stray laterally. Smaller venous channels are frequently penetrated and are managed by pressure for 5 minutes or placement of a vaginal pack. Occasionally, a retropubic space hematoma will develop, but it is self-limited, and the usual treatment is observation.

Bladder perforation occurs in 2% to 4%; the incidence decreases with surgeon experience. Once identified, this event is usually managed by withdrawal and reinsertion of the needle (

Table 41.3). When this occurs, a Foley catheter is recommended for bladder drainage. The optimal duration for bladder drainage in this setting is not known. Assuming that the sling is replaced after a perforation, it is our practice to continue drainage for 1 week, given that the perforation is almost always adjacent to the permanent implant. Bladder perforation may be minimized by hydrodissection of the retropubic space, keeping the bladder empty and directing the bladder away from the operative site with the rigid catheter guide.

There is a 2% to 3% risk of persistent urinary retention requiring sling revision. This is best performed in the first 4 to 6 weeks after surgery (e.g., before advanced scarring around the mesh). Sling revision includes exposure of the sling by sharp dissection, with midline transsection to allow retraction of the mesh away from the underside of the urethra. In some cases of retention, the tape will be found to have migrated somewhat proximally along the urethra. After sling transsection, continence is maintained in most patients, and the release of the sling allows normal voiding in most cases.

De novo urinary urgency occurs in 10% to 12%, although this symptom is typically self-limited. However, a number of patients require medical intervention. Release or loosening of the sling may help resolve severe urgency symptoms.

Exposure of the permanent sling material is a delayed complication, occurring in approximately 4% of patients within 24 months. Possible symptoms include bleeding, discharge, and dyspareunia. This complication is usually managed by excision of the exposed mesh and resuturing of the vagina.