Sterilization

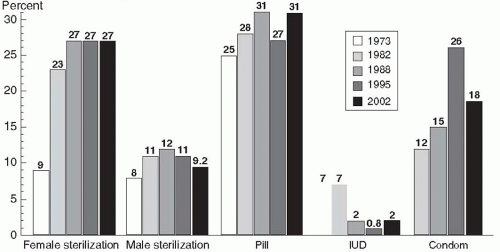

Contraceptive methods today are very safe and effective; however, we remain decades away from a perfect method of contraception for either women or men. Because reversible contraceptive methods are not perfect, more than a third of American couples use sterilization instead, and sterilization is now the predominant method of contraception in the world.

Over the past 20 years, over 1 million Americans each year have undergone a sterilization operation, and recently, more women than men. Currently, 39% of reproductive-aged American women rely on contraceptive sterilization: 27% undergo tubal occlusion (11 million women), and 11% depend on their partners’ vasectomies (4 million men).1 This same trend has occurred in Great Britain, where by age 40, more than 20% of men and women have had a sterilization procedure.2 In Spain and Italy, sterilization rates are very low, but the use of oral contraceptives and the intrauterine device (IUD) is very high.3

History

James Blundell proposed in 1823, in lectures at Guy’s Hospital in London, that tubectomy ought to be performed at cesarean section to avoid the need for repeat sections.6 He also proposed a technique for sterilization, which he later described so precisely that he must actually have performed the

operation, although he never wrote about it. The first report was published in 1881 by Samuel Lungren of Toledo, Ohio, who ligated the tubes at the time of cesarean section, as Blundell had suggested 58 years earlier.7 The Madlener procedure was devised in Germany in 1910 and reported in 1919. Because of many failures, the Madlener technique was supplanted in the United States by the method of Ralph Pomeroy, a prominent physician in Brooklyn, New York. This method, still popular today, was not described to the medical profession by Pomeroy’s associates until 1929, 4 years after Pomeroy’s death. Frederick Irving of the Harvard Medical School described his technique in 1924, and the Uchida method was not reported until 1946.

operation, although he never wrote about it. The first report was published in 1881 by Samuel Lungren of Toledo, Ohio, who ligated the tubes at the time of cesarean section, as Blundell had suggested 58 years earlier.7 The Madlener procedure was devised in Germany in 1910 and reported in 1919. Because of many failures, the Madlener technique was supplanted in the United States by the method of Ralph Pomeroy, a prominent physician in Brooklyn, New York. This method, still popular today, was not described to the medical profession by Pomeroy’s associates until 1929, 4 years after Pomeroy’s death. Frederick Irving of the Harvard Medical School described his technique in 1924, and the Uchida method was not reported until 1946.

Few sterilizations were performed until the 1930s when “family planning” was first suggested as an indication for surgical sterilization by Baird in Aberdeen. He required women to be older than 40 and to have had eight or more children. Mathematical formulas of this kind persisted through the 1960s. In 1965, Sir Dugald Baird delivered a remarkable lecture, entitled “The Fifth Freedom,” calling attention to the need to alleviate the fear of unwanted pregnancies and the important role of sterilization.8 By the end of the 1960s, sterilization was a popular procedure.

Laparoscopic methods were introduced in the early 1970s. The annual number of vasectomies began to decline, and the number of tubal occlusion operations increased rapidly. By 1973, more sterilization operations were performed for women than for men. This is accurately attributed to dramatic decreases in costs, hospital time, and pain because of the introduction of laparoscopy and minilaparotomy methods. The use of laparoscopy for tubal occlusion increased from only 0.6% of sterilizations in 1970 to more than 35% by 1975.9 Since 1975, minilaparotomy, a technique popular in the less developed world, has been increasingly performed in the United States. These methods have allowed women to undergo sterilization operations at times other than immediately after childbirth or during major surgery.

Laparoscopy and minilaparotomy have led to a profound change in the convenience and cost of sterilization operations for women. In 1970, the average woman stayed in the hospital 6.5 days for a tubal sterilization. By 1975, this had declined to 3 days, and today, women rarely remain in the hospital overnight. The shorter length of stay achieved from 1970 to 1975 represented a savings of more than $200 million yearly in health care costs and a tremendous increase in convenience for women eager to return to work and their families.10 Unlike some advances in technology, laparoscopy and minilaparotomy sterilization are technical innovations that have resulted in large savings in medical care costs.

The great majority of sterilization procedures are accomplished in hospitals by physicians in private practice, but a rapidly increasing proportion is performed outside of hospitals in ambulatory surgical settings, including physicians’ offices. In either hospital or outpatient settings, female sterilization is a very safe operation. Deaths specifically attributed to sterilization now account for a fatality rate of only 1.5 per 100,000 procedures, a mortality rate that is lower than that for childbearing (about 8 per 100,000 births in the United States).11,12 When the risk of pregnancy from contraceptive method failure is taken into account, sterilization is the safest of all contraceptive methods.

Vasectomy has long been more popular in the United States than anywhere else in the world, but why do not more men use it? One explanation is that women have chosen laparoscopic sterilization in increasing numbers. Another is that men have been frightened by reports, often from animal data, of associations with autoimmune diseases, atherosclerosis, and, most recently, prostatic cancer. Large epidemiologic studies have failed to confirm any definite adverse consequences.13 When patients consider sterilization, we can assure them that vasectomy has not been demonstrated to have any harmful effects on men’s health.14 In addition, vasectomy is less expensive than tubal sterilization, morbidity is less, and mortality is essentially zero.

Efficacy of Sterilization

Laparoscopic and minilaparotomy sterilizations are not only convenient but also almost as effective at preventing pregnancy as were the older, more complex operations. Vasectomy is also highly effective once the supply of remaining sperm in the vas deferens is exhausted. Approximately 50% of men will reach azoospermia at 8 weeks, but the time to achieve azoospermia is highly variable, reaching only about 60% to 80% after 12 weeks.15,16

| ||||||||||||

In addition to the specific operation used, the skill of the operator and characteristics of the patient make important contributions to the efficacy of female sterilization. Up to 50% of failures are due to technical errors. The methods using complicated equipment, such as springloaded clips and silastic rings, fail for technical reasons more commonly than do simpler procedures such as the Pomeroy tubal ligation.20 Minilaparotomy failures, therefore, occur much less frequently from technical errors.

It is hardly surprising that more complicated techniques of tubal occlusion have higher technical failure rates. What is surprising is the finding that characteristics of the patient influence the likelihood of failure even when technical problems are controlled for in analytical adjustments. In a careful study of this issue, two patient characteristics, age and lactation, demonstrated a significant impact.21 Patients younger than 35 years were 1.7 times more likely to become pregnant, and women who were not breastfeeding following sterilization were five times more likely to become pregnant. These findings probably reflect the greater fecundity of younger women and the contraceptive contribution of lactation.

Significant numbers of pregnancies after tubal occlusion are present before the procedure. For this reason, some clinicians routinely perform a uterine evacuation or curettage prior to tubal occlusion. It seems more reasonable (and cost effective) to exclude pregnancy by careful history taking, physical examination, and an appropriate pregnancy test prior to the sterilization procedure.22

Because method, operator, and patient characteristics all influence sterilization failures, it is difficult to predict which individual will experience a pregnancy after undergoing a tubal occlusion. Therefore, during the course of counseling, all patients should be made aware of the possibility of failure as well as the intent to cause permanent, irreversible sterility. It is important to avoid giving patients the impression that the tubal occlusion procedure is foolproof or guaranteed. Individual clinicians must be cautious judging their own success in accomplishing sterilization because failure is infrequent and many patients who become pregnant after sterilization never reveal the failure to the original surgeon.

Ectopic pregnancies can occur following tubal occlusion, and the incidence is much higher with some types of tubal occlusion.23,24,25 Bipolar tubal coagulation is more likely to result in ectopic pregnancy than is mechanical occlusion.20,26,27 The probable explanation is that microscopic fistulae in the coagulated segment connecting to the peritoneal cavity permit sperm to reach the ovum. Ectopic pregnancies following tubal ligation are more likely to occur 3 or more years after sterilization, rather than immediately after. The proportion of ectopic pregnancies is three times as high in the fourth through the 10th years after sterilization as in the first 3 years.27 For laparoscopic methods, the cumulative rate of ectopic pregnancy continues to increase for at least 10 years after surgery, reaching 17 per 1,000 for bipolar coagulation.27 Overall, however, the risk of an ectopic pregnancy in sterilized women is lower than if they had not been sterilized. Nevertheless, approximately one third of the pregnancies that occur after tubal sterilization are ectopic.27

Vaginal procedures have higher failure rates than laparoscopy or minilaparotomy, but the principal disadvantage is a higher rate of infection. Intraperitoneal infection is a rare complication of minilaparotomy or laparoscopic techniques, but in vaginal procedures, abscess formation approaches 1%.28 This risk can be reduced by the use of prophylactic antibiotics administered intraoperatively, but open laparoscopy is usually easier and safer than vaginal sterilization even in obese women.

Sterilization and Ovarian Cancer—A Benefit of Sterilization

Serous ovarian cancer, the most common ovarian cancer, originates in the fimbriae of the fallopian tubes.29,30,31 Evidence consistently indicates that tubal sterilization is associated with a major reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer.32,33,34,35,36 Evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study indicated that tubal sterilization was associated with a 67% reduced risk of ovarian cancer.32 In the prospective mortality study conducted by the American Cancer Society, women who had undergone tubal sterilization experienced about a 30% reduction in the risk of fatal ovarian cancer.33

Female Sterilization Techniques

Because laparoscopy permits direct visualization and manipulation of the abdominal and pelvic organs with minimal abdominal disruption, it offers many advantages. Hospitalization is not required; most patients return home within a few hours, and the majority return to full activity within 24 hours. Discomfort is minimal, the incision scars are barely visible, and sexual activity need not be restricted. In addition, the surgeon has an opportunity to inspect the pelvic and abdominal organs for abnormalities. The disadvantages of laparoscopic sterilization include the cost; the expensive, fragile equipment; the special training required; and the risks of inadvertent bowel or vessel injury.

Laparoscopic sterilization can be achieved with any of these methods:

1. Occlusion and partial resection by unipolar electrosurgery.

2. Occlusion and transection by unipolar electrosurgery.

3. Occlusion by bipolar electrocoagulation.

4. Occlusion by mechanical means (clips or silastic rings).

All of these methods can use an operating laparoscope alone, the diagnostic laparoscope with operating instruments passed through a second trocar, or both the operating laparoscope and secondary puncture equipment. All can be used with the “open” laparoscopic technique in which the laparoscopic instrument is placed into the abdominal cavity under direct vision to avoid the risk of bowel or blood vessel puncture on blind entry. Patient acceptance and recovery are approximately the same with all methods.

It is now apparent that the long-term failure rates for all methods are higher than previous estimates; overall, 1.85% of sterilized American women experience a failure within 10 years.37 As much as one-third of these failures are ectopic pregnancies.27 The higher failure rates with silastic rings, the Hulka-Clemens clip, and bipolar coagulation reflect the greater degree of skill required for these methods. Because of the effect of declining fecundity with increasing age, younger sterilized women are more likely to have a failure, including ectopic pregnancy, compared with older women. For these reasons, younger women seeking sterilization should consider the use of the IUD or implants, reversible methods that offer very low failure rates.

|

Life Table Cumulative Probability of Pregnancy37 |

Tubal Occlusion by Electrosurgical Methods

If electrons from an electrosurgical generator are concentrated in one location, heat within the tissue increases sharply and desiccates the tissue until resistance is so high that no more current can pass. Unipolar methods of sterilization create a dense area of current under the grasping forceps of the unipolar electrode. To complete the circuit, however, these electrons must spread through the body and be returned to the generator via a return electrode (the ground plate) that has a broad surface to minimize the density of the current to avoid burns as the electrons leave the body. “Unipolar” refers to the method that requires the patient ground plate.

Unipolar electrosurgery can create a unique electrical “capacitance” problem. A capacitor is any device that can hold an electric charge and can exist wherever an insulated material separates two conductors that have different potentials. This property of capacitance explains some of the inadvertent bowel burns that occurred with laparoscopic sterilization.39 The operating laparoscope is a hollow metal tube surrounding an active electrode, the forceps used to grasp and coagulate the tubes. When current passes through the active electrode, the laparoscope itself becomes a capacitor. Up to 70% of the current passed through the active electrode can be induced into the laparoscope. If bowel or other structures touch a laparoscope, which is insulated from the abdominal incision (e.g., by a plastic cannula), the stored electrons will be discharged at high density directly into the vital organ. This potential hazard is eliminated by using a metal trocar sleeve rather than a nonconductive sleeve. Because there is little pressure behind the electrons

from a low-voltage generator, not enough heat is generated to burn the skin as the capacitance current leaks out into the patient’s body through the metal sleeve. Even if the active electrode comes in direct contact with the laparoscope, as when a two-incision technique is used, the current will leak harmlessly through the metal trocar sleeve. The risk of inadvertent coagulation of bowel or other organs cannot be completely eliminated because all body surfaces offer a path back to the ground plate.

from a low-voltage generator, not enough heat is generated to burn the skin as the capacitance current leaks out into the patient’s body through the metal sleeve. Even if the active electrode comes in direct contact with the laparoscope, as when a two-incision technique is used, the current will leak harmlessly through the metal trocar sleeve. The risk of inadvertent coagulation of bowel or other organs cannot be completely eliminated because all body surfaces offer a path back to the ground plate.

The unipolar electrosurgical technique is straightforward. The isthmic portion of the fallopian tube is grasped and elevated away from the surrounding structures, and the electrical energy is applied until the tissue blanches, swells, and then collapses. The tube is then grasped, moving toward the uterus, recoagulated, and the steps repeated until 2 to 3 cm of tube have been coagulated. Some surgeons advise against cornual coagulation for fear it may increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy due to fistula formation.

The coagulation and transection technique is performed in a similar fashion with the same instruments. In order to transect the tube, however, an instrument designed to cut tissue must be used. The transection of tissue increases the risk of possible bleeding and does not, by itself, reduce the failure rate over coagulation alone. The specimens obtained by this method are usually coagulated beyond microscopic recognition and, therefore, will not provide pathologic evidence of successful sterilization.

The bipolar method of sterilization eliminates the ground plate required for unipolar electrosurgery and uses a specially designed forceps. One jaw of the forceps is the active electrode, and the other jaw is the ground electrode. Current density is great at the point of forceps contact with tissue, and the use of a low-voltage, high-frequency current prevents the spread of electrons. By eliminating the return electrode, the chance of an aberrant pathway through bowel or other structures is greatly reduced. There is, however, a disadvantage with this technique. Because electron spread is decreased, more applications of the grasping forceps are necessary to coagulate the same length of tube than with unipolar coagulation. As desiccation occurs at the point of high current density, tissue resistance increases, and the coagulated area eventually provides resistance to flow of the low-voltage current. Should the resistance increase beyond the voltage’s capability to push electrons through the tissue, incomplete coagulation of the endosalpinx can result.40 Bipolar coagulation is very effective only if three or more sites are coagulated on each tube.41

Bipolar cautery is safer than unipolar cautery with regard to burns of abdominal organs, but most studies indicate higher failure rates. Although the bipolar forceps will not burn tissues that are not actually grasped, care must be taken to avoid coagulating structures adherent to the tubes. For example, the ureter can be damaged when the tube is adherent to the pelvic side wall.

Tubal Occlusion with Clips and Rings

Female sterilization by mechanical occlusion eliminates the safety concerns with electrosurgery. However, mechanical devices are subject to flaws in

material, defects in manufacturing, and errors in design, all of which can alter efficacy. Three mechanical devices have been widely used and have low failure rates with long-term follow-up: the Hulka-Clemens (spring) clip, the Filshie Clip, and the silastic (Falope or Yoon) ring. Each of the three requires an understanding of its mechanical function, a working knowledge of the intricate applicator necessary to apply the device, meticulous attention to maintenance of the applicators, and skillful tubal placement. These devices are less effective when used immediately postpartum on dilated tubes.

material, defects in manufacturing, and errors in design, all of which can alter efficacy. Three mechanical devices have been widely used and have low failure rates with long-term follow-up: the Hulka-Clemens (spring) clip, the Filshie Clip, and the silastic (Falope or Yoon) ring. Each of the three requires an understanding of its mechanical function, a working knowledge of the intricate applicator necessary to apply the device, meticulous attention to maintenance of the applicators, and skillful tubal placement. These devices are less effective when used immediately postpartum on dilated tubes.

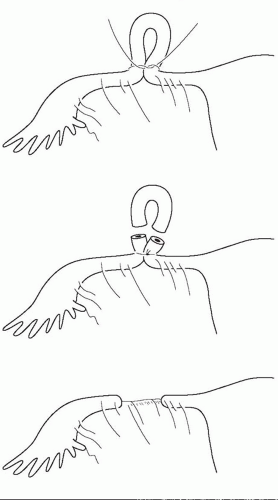

Hulka-Clemens Spring Clip

The spring clip consists of two plastic jaws made of Lexan, hinged by a small metal pin 2 mm from one end. Each jaw has teeth on the opposed surface, and a stainless steel spring is pushed over the jaws to hold them closed over the tube. A special laparoscope for one-incision application is most commonly used, although the spring clip can also be used in a two-incision procedure. The spring clip is applied at a 90-degree angle to include some mesosalpinx at the proximal isthmus of a stretched fallopian tube. The spring clip destroys 3 mm of tube and has 1-year pregnancy rates of 2 per 1,000 women but the highest 10-year cumulative failure rate.20,37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree