Intrauterine Contraception

Intrauterine contraceptives are used by over 180 million women worldwide, but only about 3 million of these are American. The growing need for reversible contraception in the United States would be well served by increasing utilization of intrauterine contraception with the intrauterine device (the IUD). The efficacy of modern IUDs in actual use is superior to that of oral contraception. Problems with IUD use can be minimized to a very low rate of minor side effects with careful screening and technique. Unfortunately, clinicians in the United States still have limited intrauterine contraception knowledge and training.1 We hope that American clinicians and patients will “rediscover” this excellent method of contraception.

History

A frequently told, but not well-documented, story assigns the first use of IUDs to caravan drivers who allegedly used intrauterine stones to prevent pregnancies in their camels during long journeys.

The forerunners of the modern IUD were small stem pessaries used in the 1800s, small button-like structures that covered the opening of the cervix and were attached to stems extending into the cervical canal.2 It is not certain whether these pessaries were used for contraception, but this seems to have been intended. In 1902, a pessary that extended into the uterus was developed by Hollweg in Germany and used for contraception. This pessary was sold for self-insertion, but the hazard of infection was great, earning the condemnation of the medical community.

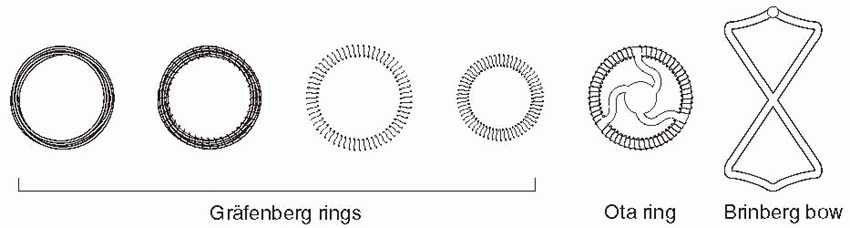

In 1909, Richter, in Germany, reported success with a silkworm catgut ring that had a nickel and bronze wire protruding through the cervix.3 Shortly after, Pust combined Richter’s ring with the old button-type pessary and replaced the wire with a catgut thread.4 This IUD was used during World War I in Germany, although the German literature was quick to report infections with its insertion and use. In the 1920s, Gräfenberg removed the tail and pessary because he believed this was the cause of infection. He reported his experience in 1930, using rings made of coiled silver and gold and then steel.5

|

The Gräfenberg ring was short-lived, falling victim to Nazi political philosophy that was bitterly opposed to contraception. Gräfenberg was jailed, but later he managed to flee Germany, dying in New York City in 1955. He never received the recognition that was his just due.

The Gräfenberg ring was associated with a high rate of expulsion. This was solved by Ota in Japan who added a supportive structure to the center of his gold- or silver-plated ring in 1934.6 Ota also fell victim to World War II politics (he was sent into exile), but his ring continued to be used.

The Gräfenberg and Ota rings were essentially forgotten by the rest of the world throughout World War II. An awareness of the explosion in population and its impact began to grow in the first 2 decades after World War II. In 1959, reports from Japan and Israel by Ishihama and Oppenheimer once again stirred interest in the rings.7,8 The Oppenheimer report was in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and several American gynecologists were stimulated to use rings of silver or silk, and others to develop their own devices.

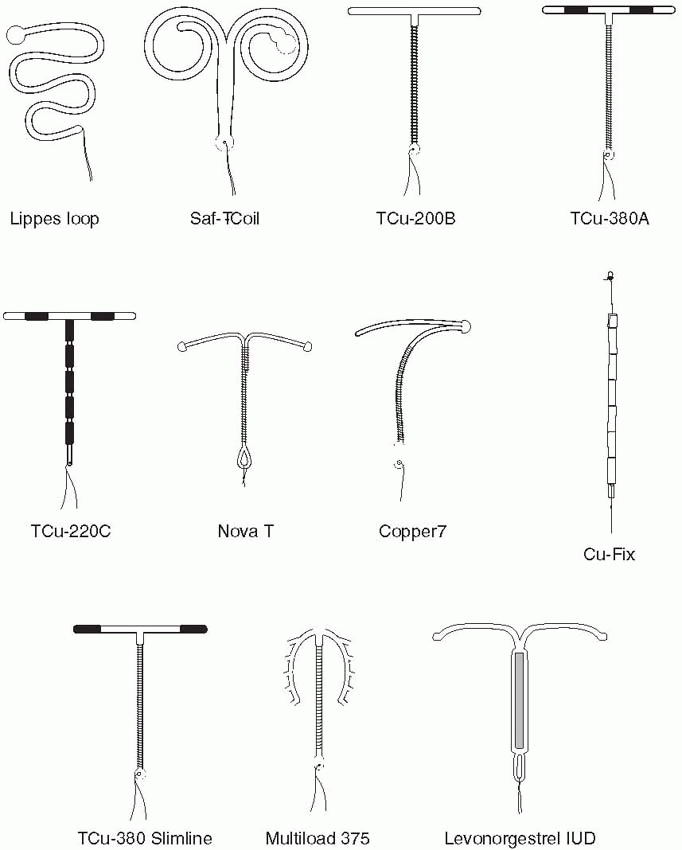

In the 1960s and 1970s, the IUD thrived. Techniques were modified and a plethora of types were introduced. The various devices developed in the 1960s were made of plastic (polyethylene) impregnated with barium sulfate so that they would be visible on an x-ray. The Margulies Coil, developed by Lazer Margulies in 1960 at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City, was the first plastic device with a memory, which allowed the use of an inserter and reconfiguration of the shape when it was expelled into the uterus. The Coil was a large device (sure to cause cramping and bleeding), and its hard plastic tail proved risky for the male partner.

In 1962, the Population Council, at the suggestion of Alan Guttmacher, who that year became president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, organized the first international conference on IUDs in New York City. It was at this conference that Jack Lippes of Buffalo presented experience with his device, which fortunately as we will see, had a single filament thread as a tail, the first IUD to use a tail to establish position and for easy removal. The Margulies Coil was rapidly replaced by the Lippes Loop. Acquired by the Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation in 1966, it quickly became the most widely prescribed IUD in the United States in the 1970s. The Population Council acquired international rights for the Lippes Loop, and it became used by millions of women throughout the world.

A former World War II test pilot and engineer, Paul H. Bronnenkant, was making plastic parts for jukeboxes in his company, Hallmark Plastics, located next door to the Wurlitzer factory in Buffalo. Lippes’ enlistment of Bronnenkant in 1959 to develop his polyethylene and barium sulfate loop was so successful that Bronnenkant became an energetic advocate of the Lippes Loop; he carried heavy metal molds throughout the Far East to establish local production. A succeeding company, Finishing Enterprises, directed by Bronnenkant’s son, Lance Bronnenkant, was the original and is the continuing manufacturer of the TCu-380A since its U.S. approval in 1984. Beginning in 2004, an affiliate of Finishing Enterprises, FEI Women’s Health, assumed responsibility for both the manufacturing and the marketing of the ParaGard TCu-380A IUD in the United States. In 2005, FEI Women’s Health was acquired by Duramed Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Barr Pharmaceuticals.

The 1962 conference also led to the organization of a program established by the Population Council, under the direction of Christopher Tietze, to evaluate IUDs, the Cooperative Statistical Program. The Ninth Progress Report in 1970 was a landmark comparison of efficacy and problems with the various IUDs in use.9

Many other devices came along, but, with the exception of the four sizes of Lippes Loops and the two Saf-T-Coils, they had limited use. Stainless steel devices incorporating springs were designed to compress for easy insertion, but the movement of these devices allowed them to embed in the uterus, making them too difficult to remove. The Majzlin Spring is a memorable example.

The Dalkon Shield was introduced in 1970. Within 3 years, a high incidence of pelvic infection was recognized. There is no doubt that the problems with the Dalkon Shield were due to defective construction, pointed out as early as 1975 by Tatum et al.10 The multifilamented tail (hundreds of fibers enclosed in a plastic sheath) of the Dalkon Shield provided a pathway for bacteria to ascend protected from the barrier of cervical mucus.

Although sales were discontinued in 1975, a call for removal of all Dalkon Shields was not issued until the early 1980s. The large number of women with pelvic infections led to many lawsuits against the pharmaceutical company, ultimately causing its bankruptcy. Unfortunately, the Dalkon Shield problem tainted all IUDs, and for a long time, media and the public in the United States inappropriately regarded all IUDs in a single, generic fashion.

About the time of the introduction of the Dalkon Shield, the U.S. Senate conducted hearings on the safety of oral contraception. Young women who were discouraged from using oral contraceptives after these hearings turned to IUDs, principally the Dalkon Shield, which was promoted as suitable for nulliparous women. Changes in sexual behavior in the 1960s and 1970s, and failure to use protective contraception (condoms and oral contraceptives), led to an epidemic of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) for which IUDs were held partially responsible.11

and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) for which IUDs were held partially responsible.11

The first epidemiologic studies of the relationship between IUDs and PID used women who depended on oral contraception or barrier methods as controls, and who were, therefore, at reduced risk of PID compared with noncontraceptors and IUD users.12,13 In addition, these first studies failed to control for the characteristics of sexual behavior that are now accepted as risk factors for PID (multiple partners, early age at first intercourse, and increased frequency of intercourse).14 The Dalkon Shield magnified the risk attributed to IUDs because its high failure rate in young women who were already at risk of STIs led to septic spontaneous abortions and, in some cases, death.15 Reports of these events led the American public to regard all IUDs as dangerous, including those that, unlike the Dalkon Shield, had undergone extensive clinical trials and postmarketing surveillance.

The 1980s saw the decline of IUD use in the United States as manufacturers discontinued marketing in response to the burden of litigation. Despite the fact that most of the lawsuits against the copper devices were won by the manufacturer, the cost of the defense combined with declining use affected the financial return. It should be emphasized that this action was the result of corporate business decisions related to concerns for profit and liability, not for medical or scientific reasons. It was not until 1988 that the IUD was returned to the U.S. market.

The reason for the decline in the United States was the consumer fear of IUD-related pelvic infection. The final blow to the IUD in the United States came in 1985 with the publication of two reports indicating that the use of IUDs was associated with tubal infertility.16,17 Later, better controlled studies identified the Dalkon Shield as a high-risk device and failed to demonstrate an association between PID and other IUDs, except during the period shortly after insertion. Efforts to point out that the situation was different for the copper IUDs, and that, in fact, PID was not increased in women with a single sexual partner,18 failed to prevent the withdrawal of IUDs from the American market and the negative reaction to IUDs by the American public. Ironically, the IUD declined in the country that developed the modern IUD.

The number of reproductive-aged women using the IUD in the United States decreased by two thirds from 1982 to 1988 and further decreased in 1995, from 7.1% to 2% to 0.8%, respectively.19 Since 1995, the use of the IUD in the United States has climbed to 5%, reflecting the popularity of the levonorgestrel-releasing system.20 In the rest of the world, the IUD is the most widely used method of reversible contraception; currently, more than 180 million women use the IUD, 16.5% of reproductive age women in developing countries and 9.4% in the developed world.21

The Modern IUD

The addition of copper to the IUD was suggested by Jaime Zipper of Chile, whose experiments with metals indicated that copper acted locally on the endometrium.23 Howard Tatum in the United States combined Zipper’s suggestion with the development of the T-shape to diminish the uterine reaction to the structural frame and produced the copper-T. The first copper IUD had copper wire wound around the straight shaft of the T, the TCu-200 (200 mm2 of exposed copper wire), also known as the Tatum-T.24 Tatum’s reasoning was that the T-shape would conform to the shape of the uterus in contrast to the other IUDs that required the uterus to conform to their shape. Furthermore, the copper IUDs could be much smaller than those of simple, inert plastic devices and still provide effective contraception. Studies indicate that copper exerts its effect before implantation of a fertilized ovum; it may be spermicidal, or it may diminish sperm motility or fertilizing capacity. The addition of copper to the IUD and reduction in the size and structure of the frame improved tolerance, resulting in fewer removals for pain and bleeding.

The Cu-7 with a copper wound stem was developed in 1971 and quickly became the most popular device in the United States. Both the Cu-7 and the Tatum-T were withdrawn from the U.S. market in 1986 by G. D. Searle and Company.

IUD development continued, however. More copper was added by Population Council investigators, leading to the TCu-380A (380 mm2 of exposed copper surface area) with copper wound around the stem plus a copper sleeve on each horizontal arm.25 The “A” in TCu-380A is for arms, indicating the importance of the copper sleeves. Making the copper solid and tubular increased effectiveness and the lifespan of the IUD. The TCu-380A has been in use in more than 30 countries since 1982, and, in 1988, it was marketed in the United States as the “ParaGard.”

Types of IUDs

Unmedicated IUDs

Copper IUDs

The first copper IUDs were wound with 200 to 250 mm2 surface area of wire, and two of these are still available (except in the United States): the TCu-200 and the Multiload-250. The more modern copper IUDs contain more copper, and part of the copper is in the form of solid tubular sleeves, rather than wire, increasing efficacy and extending lifespan. This group of IUDs is represented in the United States by the TCu-380A (the ParaGard) and in the rest of the world by the TCu-220C, the Nova T, and the Multiload-375. The Sof-T is a copper IUD used only in Switzerland.

|

The TCu-380A is a T-shaped device with a polyethylene frame holding 380 mm2 of exposed surface area of copper that provides contraception for at least 10 years. Although the data are sparse, wearing the TCu-380A for 20 years carries only a very small risk of pregnancy.28 The pure electrolytic copper wire wound around the 36-mm stem weighs 176 mg, and copper sleeves on the horizontal arms weigh 66.5 mg. A polyethylene monofilament is tied through the 3 mm ball on the stem, providing two white threads for detection and removal. The ball at the bottom of the stem helps reduce the risk of cervical perforation. The IUD frame contains barium sulfate, making it radiopaque. The TCu-380Ag is identical to the TCu-380A, but the copper wire on the stem has a silver core to prevent fragmentation and extend the lifespan of the copper. The TCu-380 Slimline has the copper sleeves flush at the ends of the horizontal arms to facilitate easier loading and insertion. The performance of the TCu-380Ag and the TCu-380 Slimline is equal to that of the TCu-380A.29,30

The Multiload-375 has 375 mm2 of copper wire wound around its stem. The flexible arms were designed to minimize expulsions. This is a popular device in many parts of the world. The Multiload-375 and the TCu-380A are similar in their efficacy and performance.31

The Nova T is similar to the TCu-200, containing 200 mm of copper; however, the Nova T has a silver core to the copper wire, flexible arms, and a large, flexible loop at the bottom to avoid injury to cervical tissue. There was some concern that the efficacy of the Nova T decreased after 3 years in World Health Organization (WHO) data; however, results from Finland and Scandinavia indicate low and stable pregnancy rates over 5 years of use.31

The CuSAFE-300 IUD has 300 mm2 of copper in its vertical arm and a transverse arm with sharply bent ends that are adapted to the uterine cavity and help hold this IUD in the fundus. It is made from a more flexible plastic and is smaller than the world’s two most popular IUDs, the TCu-380A and the Multiload-375. Pregnancy rates with the CuSAFE-300 are comparable to these two devices, but rates of removal for pain and bleeding are reported to be lower.32

The Hormone-Releasing IUD

The LNG-IUS (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, Mirena), manufactured by Schering-Oy in Finland, releases in vitro 20 µg of levonorgestrel per day.33 This T-shaped device has a collar attached to the vertical arm, which contains 52 mg levonorgestrel dispersed in polydimethylsiloxane and released initially at a rate of 20 µg/d in vivo, progressively declining (reaching half of the initial rate after 5 years). The levonorgestrel IUS is approved for 5 years, but lasts for 7 years, and perhaps up to 10 years, and reduces menstrual blood loss and pelvic infection rates.34,35,36

The levonorgestrel IUS is about as effective as endometrial ablation for the treatment of menorrhagia.37,38 The local progestin effect directed to the endometrium can be utilized in patients on tamoxifen,39 patients

with dysmenorrhea,40 and in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen therapy.41,42,43,44,45,46 A slightly smaller T-shaped device that releases 20 µg of levonorgestrel daily is called the Femilis LNG-IUS.47

with dysmenorrhea,40 and in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen therapy.41,42,43,44,45,46 A slightly smaller T-shaped device that releases 20 µg of levonorgestrel daily is called the Femilis LNG-IUS.47

Other IUDs

The Ombrelle-250 and Ombrelle-380, designed to be more flexible in order to reduce expulsion and side effects, have been marketed in France. A frameless IUD, the FlexiGard (also known as the Cu-Fix or the GyneFIX), invented by Dirk Wildemeersch in 1983 in Belgium, consists of six copper sleeves (330 mm2 of copper) strung on a surgical nylon (polypropylene) thread that is knotted at one end. The knot is pushed into the myometrium during insertion with a notched needle that works like a miniature harpoon. Because it is frameless, it has a low rate of removal for bleeding or pain, but a more difficult insertion may yield a higher expulsion rate.49,50 However, when inserted by experienced clinicians, the expulsion rate is very low, and the device is especially suited for nulligravid and nulliparous women.51,52,53 This IUD is increasingly popular in Europe. A shorter system combined with a reservoir for the sustained release of 14 µg levonorgestrel per day (FibroPlant) is being tested for perimenopausal and postmenopausal use.54,55 FibroPlant effectively treats endometrial hyperplasia and menorrhagia.56,57

Mechanism of Action

The contraceptive action of all IUDs is mainly in the uterine cavity. Ovulation is not affected, and the IUD is not an abortifacient.58,59,60 It is currently believed that the mechanism of action for IUDs is the production of an intrauterine environment that is spermicidal.

Nonmedicated IUDs depend for contraception on the general reaction of the uterus to a foreign body. It is believed that this reaction, a sterile inflammatory response, produces tissue injury of a minor degree but sufficient enough to be spermicidal. Very few, if any, sperm reach the ovum in the fallopian tube. Normally cleaving, fertilized ova cannot be obtained by tubal flushing in women with IUDs in contrast to noncontraceptors, indicating the failure of sperm to reach the ovum, and, thus, fertilization does not occur.61 In women using copper IUDs, sensitive assays for human chorionic gonadotropin do not find evidence of fertilization.62,63 This is consistent with the fact that the copper IUD protects against both intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies.

The copper IUD releases free copper and copper salts that have both a biochemical and morphologic impact on the endometrium and also produce alterations in cervical mucus and endometrial secretions. There is no measurable increase in the serum copper level. Copper has many specific actions, including the enhancement of prostaglandin

production and the inhibition of various endometrial enzymes. The copper IUD is associated with an inflammatory response, marked by production in the endometrium of cytokine peptides known to be cytotoxic.64 An additional spermicidal effect probably takes place in the cervical mucus.

production and the inhibition of various endometrial enzymes. The copper IUD is associated with an inflammatory response, marked by production in the endometrium of cytokine peptides known to be cytotoxic.64 An additional spermicidal effect probably takes place in the cervical mucus.

The progestin-releasing IUD adds the endometrial action of the progestin to the foreign body reaction. The endometrium becomes decidualized with atrophy of the glands.65 The progestin IUD probably has two mechanisms of action: inhibition of implantation and inhibition of sperm capacitation, penetration, and survival. The levonorgestrel IUS produces serum concentrations of the progestin about half those of Norplant so that ovarian follicular development and ovulation are also partially inhibited; after the first year, cycles are ovulatory in 50% to 75% of women, regardless of their bleeding patterns.66 Finally, the progestin IUD thickens the cervical mucus, creating a barrier to sperm penetration.

Following removal of IUDs, the normal intrauterine environment is rapidly restored. In large studies, there is no delay, regardless of duration of use, in achieving pregnancy at normal rates, which belies the assertion that IUD use is associated with infection leading to infertility.67,68,69,70 There has been no significant difference in cumulative pregnancy rates between parous and nulliparous or nulligravid women.69,70

Noncontraceptive Benefits with the Levonorgestrel IUS

Because of the favorable impact of locally released progestin on the endometrium, the levonorgestrel IUS is very effective for the treatment of menorrhagia, more effective than the administration of oral progestins, steroid contraceptives, or inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis, and compares favorably with surgical treatment (hysterectomy or endometrial ablation).37,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82

The progestin IUD rapidly decreases dysmenorrhea and menstrual blood loss (about 40% to 50%); with the levonorgestrel IUS, bleeding over time can be reduced by 90% and about 30% to 40% of women become amenorrheic 1 year after insertion.83,84,85 Average long-term hemoglobin and iron levels increase compared with preinsertion values.86

Bleeding is even reduced in the presence of leiomyomas.87,88,89,90,91 There is some evidence that this IUD reduces the prevalence of myomas and the uterine volume in the presence of myomas.87,88,91,92,93 Not all women with myomas respond favorably to the levonorgestrel IUS; this is usually because of the presence of submucosal myomas.94 The levonorgestrel IUS also effectively reduces uterine volume and relieves dysmenorrhea secondary to adenomyosis.95,96,97

Women with hemostatic disorders, such as von Willebrand’s disease, and women who are anticoagulated commonly have heavy menstrual bleeding. The insertion of the levonorgestrel IUS effectively reduces the amount of bleeding in many, but not all, of these patients, and there is a suggestion that with time the beneficial effect wanes and earlier replacement is necessary.98,99,100,101,102

In a randomized, 5-year trial comparing a copper IUD with the levonorgestrel IUS, pelvic infection was lower than the incidence in a general population with both devices, but the rate with the levonorgestrel IUS was significantly lower compared with the copper IUD.103

The levonorgestrel IUS has been used successfully to treat endometriosis, and especially pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis.40,104,105,106,107,108 Results may even be better than with GnRH agonist treatment.109 The advantages of levonorgestrel IUS treatment of endometriosis include many years of efficacy, fewer side effects, and contraception.

The levonorgestrel IUS effectively protects the endometrium against hyperplasia and polyps in women using tamoxifen or postmenopausal estrogen therapy.39,41,42,43,44,45,110,111,112 In addition, this IUD can be used to treat endometrial hyperplasia.57,113,114,115,116,117 Comparison studies indicate that the levonorgestrel IUS is as effective, and probably better than standard treatment with an oral progestin.114,118,119 However, the persistence of atypia at biopsy follow-up after 6 months is an indication that regression is unlikely to occur.

Although the levonorgestrel IUD confidently provides good protection against endometrial hyperplasia, clinicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion of unusual bleeding (bleeding that occurs after a substantial period of amenorrhea) and aggressively assess the endometrium. At least two cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma have been identified in users of the levonorgestrel IUS.120,121 As noted, however, many studies have documented protection against and even regression of endometrial hyperplasia.

Summary of noncontraceptive benefits with the levonorgestrel IUS

Reduction of heavy menstrual bleeding and improvement of related anemia.

Treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Reduction of myoma prevalence as well as uterine volume and bleeding associated with myomas.

Decrease in uterine volume and pain associated with adenomyosis.

Reduction of menstrual bleeding in women with hemostatic disorders and in anticoagulated women.

Protection against PID.

Treatment of endometriosis and pain associated with endometriosis.

Suppression of endometriosis.

Protection against endometrial hyperplasia and polyps associated with postmenopausal estrogen therapy or tamoxifen treatment.

Prevention of ectopic pregnancy.

Reduction of endometrial cancer risk.

Efficacy of IUDs

Intrauterine Pregnancy

The TCu-380A is approved for use in the United States for 10 years. However, the TCu-380A has been demonstrated to maintain its efficacy over at least 12 years of use.122 As previously noted, based on a small number of long-term users, wearing the TCu-380A for 20 years carries a very small risk of pregnancy.28 The TCu-200 is approved for 4 years and the Nova T for 5 years. The levonorgestrel IUD can be used for at least 7 years and probably for 10 years.31,123 The levonorgestrel device that releases 15 to 20 µg levonorgestrel per day is as effective as the new copper IUDs that contain more than 250 mm2 of copper surface area.30,34,124,125

The nonmedicated IUDs never have to be replaced. The deposition of calcium salts on the IUD can produce a structure that is irritating to the endometrium. If bleeding increases after a nonmedicated IUD has been in place for some time, it is worth replacing it. Some clinicians (as do we) recommend replacing all older IUDs with the new, more effective medicated IUDs.

|

Considering all IUDs together, the actual use failure rate in the first year is approximately 3%, with a 10% expulsion rate and a 15% rate of removal, mainly for bleeding and pain. With increasing duration of use and increasing age, the failure rate decreases, as do removals for pain and bleeding. The performance of the TCu-380A in recent years, however, has proved to be superior to previous IUDs.

Ten-Year Experience with ParaGard, TCu-380A | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree