FIGURE 19-1 Frontal plain radiograph demonstrating a right Sprengel deformity.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What is Sprengel deformity?

- What are the associated conditions?

- How is Sprengel deformity classified?

- What are the surgical indications?

- What procedures may be performed for Sprengel’s?

- What complications may occur from surgical reconstruction?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Etiology and Epidemiology

When all is said and done, as a rule, more is said than done.

—Lou Holtz

While described by several surgeons prior to 1891, Sprengel is attributed with describing the congenital abnormality of the scapula that now bears his name.1,2 While Sprengel deformity is often referred to as congenital elevation of the scapula, in fact, it represents a failure of the normal descent or caudal migration of the scapula, which occurs during the 9th to 12th week of embryonic development. As the scapula typically migrates from a sagittal to coronal position, patients with Sprengel deformity will have the scapula protracted, with the inferomedial angle medial and the glenoid tilting inferiorly. In addition to the failure of descent, the affected scapula is often smaller, hypoplastic, and dysmorphic.

The etiology of Sprengel deformity remains unknown. Similarly, few definitive statements can be made regarding the epidemiology for Sprengel deformity, owing to its relative rarity and paucity of published information. In general, males and females are equally affected, and bilateral involvement may occur. While most cases are sporadic, an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern has been proposed.3 A number of associated conditions have been described, most notably Klippel-Feil syndrome (congenital cervical spine fusions), congenital scoliosis, and shoulder girdle deficiencies.

Clinical Evaluation

While the scapula is undescended at birth, often the aesthetic differences are subtle. With continued growth, the deformity becomes more apparent, and thus the diagnosis is often delayed in children without more extensive spinal and shoulder girdle congenital differences.

Patients will present with aesthetic differences in scapular position and shoulder height, of varying severity. Shoulder abduction and scapulothoracic motion are limited, often resulting in functional limitations with overhead and away from body activities. Inspection will reveal a small, high-riding scapula, often with malrotation and inferior tilt. Careful palpation will allow for identification of an omovertebral bone, an abnormal bony, cartilaginous, or fibrous connection between the cervical spine and the superomedial scapula thought to be present in approximately one-third of patients. Children with associated Klippel-Feil syndrome or congenital rib anomalies may present with torticollis, scoliosis, thoracic insufficiency, and other manifestations of their spinal/thoracic condition.

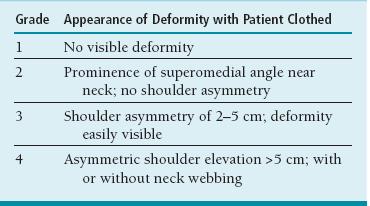

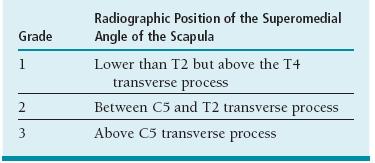

A number of classification systems have been proposed to characterize the severity of deformity. Traditionally, the Cavendish classification has been used to characterize the clinical deformity with the patient clothed4 (Table 19.1). Grade 1 deformities present without any visible deformity. Grade 2 deformity results in a mild prominence of the superomedial angle of the scapula. Grade 3 deformity signifies shoulder asymmetry of 2 to 5 cm. Grade 4 deformity results in >5 cm of shoulder height asymmetry. Rigault et al.5 proposed a radiographic classification based on the position of the superomedial angle of the scapula (Table 19.2).

Table 19.1 Cavendish classification of Sprengel deformity

Table 19.2 Rigault Radiographic classification of Sprengel deformity

Surgical Indications

I don’t believe the old statement, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” If that were the case, then Cadillacs and Jaguars and Mercedes would never make a change. I’ve always looked for ways to make things better.

—Vic Bubas

While the surgical indications for Sprengel deformity continue to evolve, in general, surgical reconstruction may be considered for patients at 3 to 4 years of age with severe deformity and functional limitations. While some authors have proposed surgical treatment based upon Cavendish or Rigault classification, every patient is different, and it is difficult to correlate aesthetic differences and shoulder impairment with clinical or radiographic appearance.6–9 Surgical treatment is not recommended for mild aesthetic differences in the absence of pain or functional limitations.

A fundamental tenet of pediatric orthopaedic surgery is that surgical treatment should only be recommended when the natural history can be favorably altered. Unfortunately, the natural history of Sprengel deformity is not well characterized. The best insight into the natural history of this condition comes from Farsetti et al.,6 who reported on 14 patients with Cavendish grade 1 to 3 Sprengel deformity observed until the ages of 18 to 67 years. One-half had mild-to-moderate pain with activity, and shoulder abduction was restricted in all. While there were no improvements in deformity over time, there were no cases of progressive deformity. When compared with a similar cohort of patients who underwent operative reconstruction, surgical patients had improved shoulder abduction of about 40 degrees, improved aesthetics, and no cases of recurrent deformity.

While a host of procedures have been proposed, most reconstructive strategies are variations of either the Woodward or Green procedures.10,11 The Woodward procedure is preferred by most due to its relative technical ease and potential biomechanical advantage of displacing the muscle origins inferiorly, thereby rotating and lowering the scapula.12,15

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Resection of Superomedial Angle of Scapula

Resection of Superomedial Angle of Scapula

Some have advocated simple resection of the prominent superomedial angle of the scapula, in essence excising the major cause of the aesthetic difference.4,13,14 While this may take away some of the visible bony bump, it does not address the abnormal elevation or the functionally limiting inferior tilt of the glenoid. For this reason, we rarely perform this procedure alone. However, it will favorably change the appearance of the neck line.

Modified Woodward Procedure

Modified Woodward Procedure

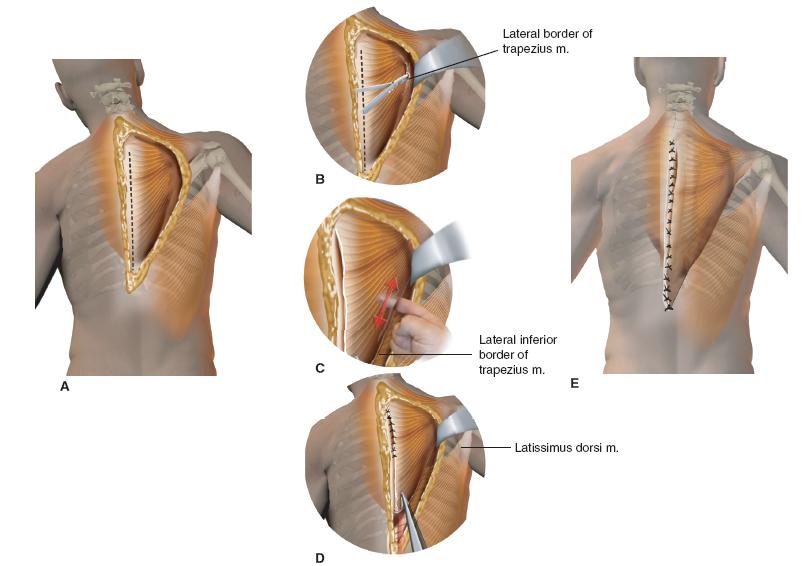

The patient is placed in the prone position, with care made to provide adequate padding of all bony prominences and sites of potential nerve compression (Figure 19-2). Adequate elevation of the thorax off the operating room table will facilitate ventilation and anesthesia, and the upper limbs should not be positioned in excessive abduction or extension to avoid positional brachial plexus traction injuries. A wide surgical field is sterilely prepped and draped, allowing access to the neck, thorax, upper lumbar spine, bilateral scapulae, and ipsilateral upper extremity.

FIGURE 19-2 The modified Woodward technique. (A) A midline incision is created. (B, C) The lateral border of the trapezius is identified and trapezius seindentted from the underlying latissimus dorsi. (D) The trapezius origin is elevated. (E) After the omovertebral connections are removed and scapula mobilized, the trapezius is advanced and repaired.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree