Instrumentation

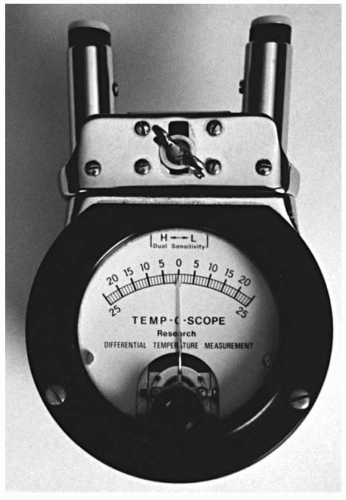

The purpose of skin temperature analysis (e.g., Tempo-scope, Nervoscope) is to obtain objective neurologic evidence of a VSC and to monitor patient care. There is a probable connection between the nervous system and intersegmental variations in skin temperature (

34). Studies have been conducted to assess the reliability of the use of temperature differential instrumentation (

35,

36).

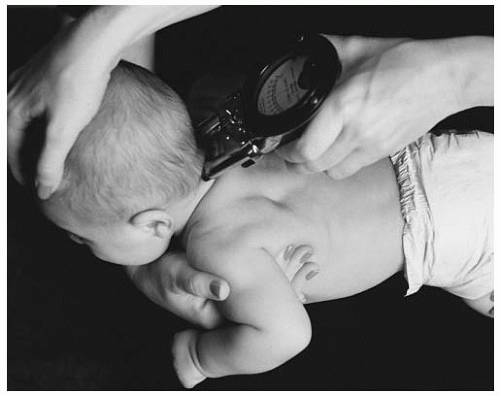

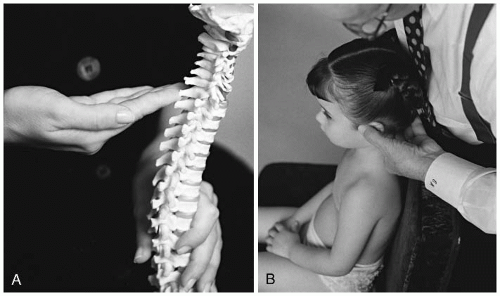

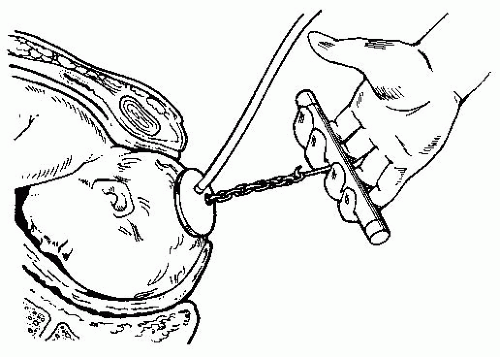

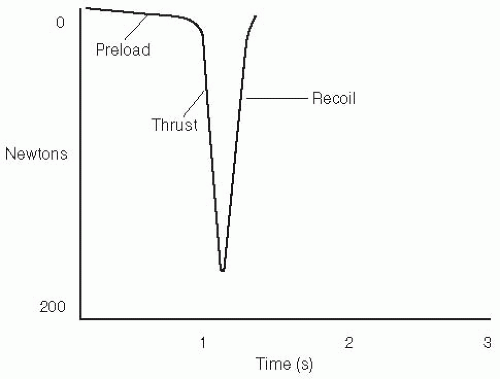

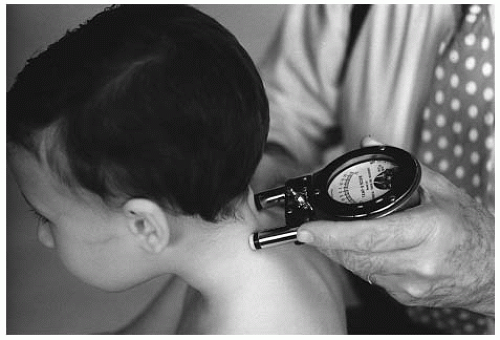

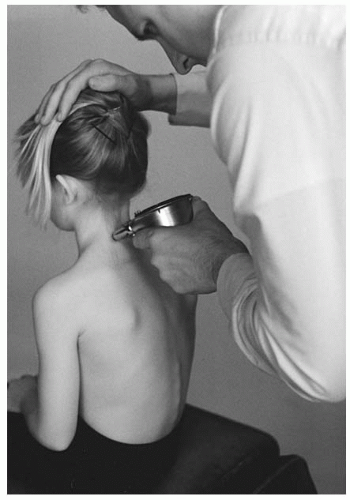

The Temp-o-scope (

Fig. 5-20) and other similar instruments provide a qualitative assessment of thermal asymmetry. The instrument detects the temperature on both sides of the spine. The method for conducting the exam is dynamic scanning. A bilateral skin temperature difference is depicted as meter needle movement to one side or the other. The “reading” or “break” in temperature symmetry is considered significant if an abrupt “over and back” needle movement is seen over a distance of one spinal segment. The amount of the temperature differential is thought to be directly proportional to the amount of neurophysiologic involvement due to the presence of VSC (

37). The spinal subluxation in the acute stage often reveals a large variation in temperature. The temperature differential that diminishes gradually is interpreted as improvement in the aberrant neurophysiology. Monitoring the intersegmental heat differential is one of several parameters of assessing and gauging patient progress in response to specific spinal adjusting.

Table 5.1 lists the corresponding segmental level of temperature differentials.

The procedure of scanning small sections of the spinal column one after another is recommended for

the paraspinal skin temperature instruments (

35). To prevent the formation of air gaps at the skin and thermocouple interface, the probes are maintained in perpendicular contact with the skin surface using sufficient pressure. The scanning glide is caudad to cephalad for T2-C0 and cephalad to caudad for T2-S2 (S3 in the smaller patient). The nonamplified instrument should have a glide speed that does not exceed 0.5 to 1.0 cm/s (

37). To confirm a suspected temperature differential at a segmental level, the scan should be repeated several times. The accentuated differentials with a repeated scanning procedure are considered more significant than those that diminish. The validity of the procedure is decreased when the existence of moles or other lesions (e.g., blemishes, scar tissue, cysts) are in the path of the instrument glide. The glide and orientation of the instrumentation is modified for the presence of spinal curvature (i.e., scoliosis). Because of the rolling, loose skin of the newborn/infant, any positive findings must be substantiated with other objective findings (e.g., tenderness or edema).

The existence of an intersegmental temperature differential does not, by itself, determine the presence of the VSC. A spinal level with neurophysiologic involvement is not considered to be a subluxation when the presence of other subluxation parameters do not exist. Aberrant nervous system activity can occur at hypermobile functional spinal units (FSUs). Hypermobility of the FSU can be a compensation for a restricted and subluxated FSU at another level, typically below the hypermobile segment (

38).

C0-C1 Temperature Scanning Procedure The neonate/infant is positioned across the lap or chest of the parent. The patient’s head should be maintained in a neutral position during the scan. The toddler and older child is seated on the cervical chair to perform the procedure. In the upper cervical region the temperature differentials occur close together. The close proximity of C0-C2 makes it difficult to determine the specific spinal level of the reading and must be confirmed with other objective findings. Suboccipital hair may also produce a spurious reading.

Radiographic Analysis

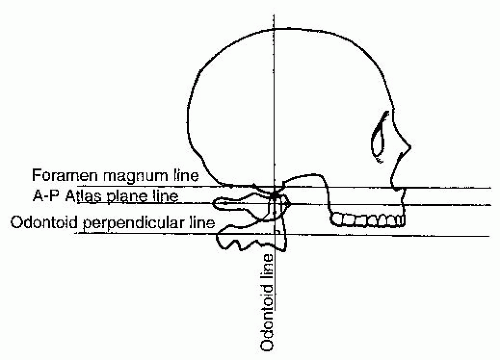

The lateral neutral posture of the occiput is analyzed in relationship to the atlas (see

Chapter 4). The radiographic line that is drawn is called the foramen magnum line (FML). Because of the difficulty in identifying landmarks, assessing this region is performed by qualitative inspection. To create a maximal opening for the spinal canal, the foramen magnum line is fairly parallel to the AP atlas plane line. Deviation of the line in hyperflexion or hyperextension is considered abnormal. This

assessment can be further substantiated with stress radiographic studies in flexion and extension and clinical assessments (

Fig. 5-21).

On the lateral radiograph the FML is altered in relationship to the AP atlas plane line. The FML will converge posterior on the AP atlas line with the AS condyle, reducing the space between the posterior arch of atlas and the foramen magnum. The PS condyle will appear as a convergence of the two lines anteriorly, increasing the space between the posterior arch of atlas and the foramen magnum.

The AP open mouth (APOM) radiograph is used to determine if a right superior (RS) (-θZ), left superior (LS) (+θZ), or axial rotation (Y axis) exists. Lateral flexion positional dyskinesia (RS or LS) is determined by the transverse condyle line. The transverse condyle line is scribed by like points on both sides of the condyles. The like points are the mastoid notches (the grooves of the mastoid process on the temporal bones). Once the line has been drawn, it is compared to the atlas transverse plane line. It is considered to be normal when the two drawn lines are parallel in the coronal plane. A misalignment will manifest a divergence of the transverse condyle line from the atlas transverse plane line. An LS (+θZ) listing (divergence) will also appear as lateral flexion to the right side.

Condyle Y-axis rotation also is analyzed from the AP (APOM) radiograph. For a rotational subluxation to exist, it must also appear with a PS or AS and an LS or RS listing. If the condyle is in a rotational misalignment, the atlas will compensate with opposite rotation on the same side of misalignment. To list the condyle rotation, the atlas plane line is read for its axial compensation. The lateral mass of atlas will be smaller (posterior) if the condyle has rotated anteriorly. If the condyle has rotated posteriorly, the lateral mass of atlas will appear wider (anterior) to compensate for the axial rotation. The condyle rotation is listed as LP, LA, RP, or RA. The rotational misalignment should always be listed last (e.g., PSRSRP) (

Table 5.2).

AS Condyle (-θX)

The AS condyle subluxation will reveal fixation and discomfort as the condyle is glided from anterior to posterior during motion palpation. Edema or bogginess is more difficult to assess. Lateral upright visual inspection will reveal a superior gaze to “the heavens.” The more severe the AS condyle subluxation, the greater likelihood of more severe neurological manifestations. A low Apagar score and depressed infant reflexes may be associated with this positional dyskinesia. The newborn or infant may be a slow developer or, in more extreme cases, can be at high risk (e.g., sudden infant death syndrome, sleep apnea). These patients have a tendency to be poor thrivers (e.g., low weight, poor appetite, weak cry). In the older infant, toddler, and preschooler, the parent may inform you that the child “head bangs” the crib or wall to fall asleep or when upset.

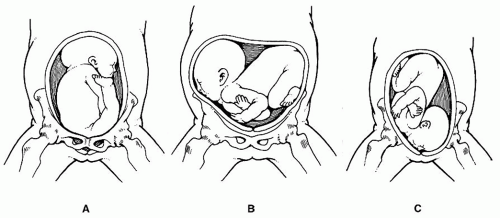

The AS condyle is not a common subluxation. It should be suspected if facial or brow trauma has occurred. Positions of in-utero constraint (e.g., brow or facial), obstetrical trauma, or a fall from a height (e.g., changing table, couch) are a few of the possible mechanisms of injury. An automobile accident with the child unrestrained or the toddler falling from a height and hitting the forehead can also induce the AS condyle subluxation. An unusual injury history given by the parent or guardian that does not correlate with typical AS injuries should alert the doctor to the possibility of child abuse.

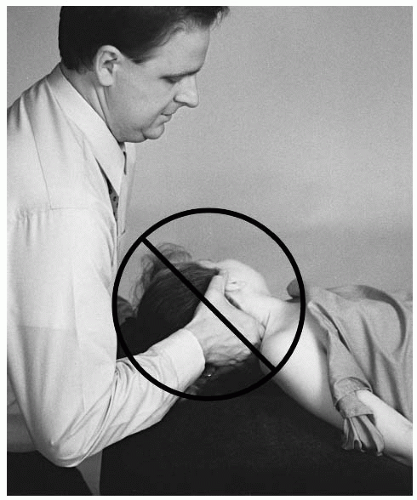

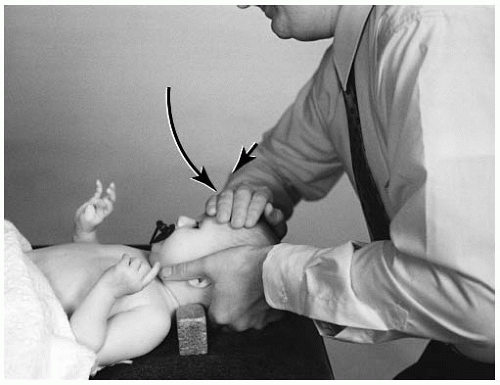

The AS condyle adjustment is performed supine on the newborn and infant. The sitting position set-up is usually performed once the cervical musculature is developed (e.g., in the toddler or preschooler). A condyle block (

Fig. 5-22) is used in all AS condyle adjustments. Once the correct size of condyle block is selected, it is placed under the cervical spine to support C1 to C7. The purpose of the condyle block is to stabilize the cervical spine when the thrust is performed.

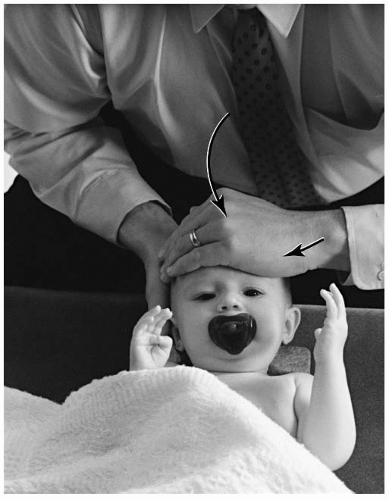

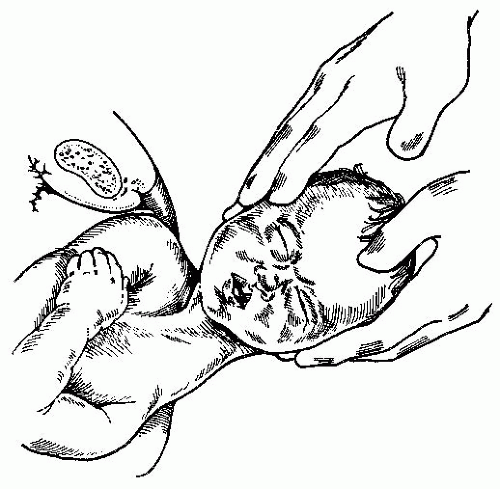

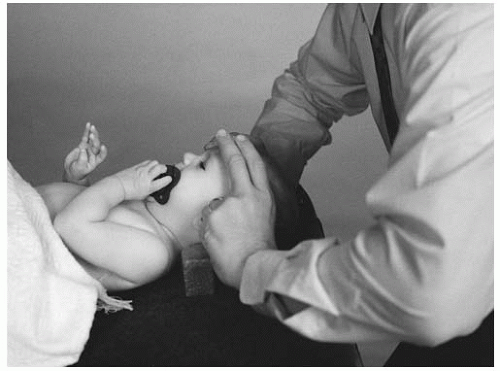

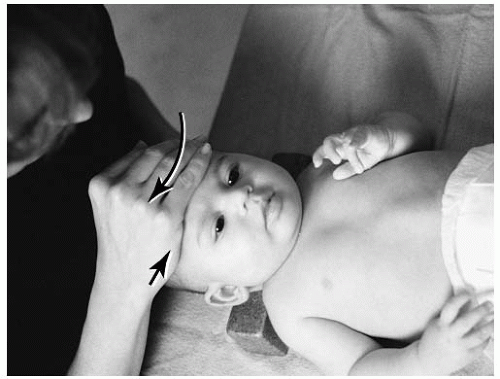

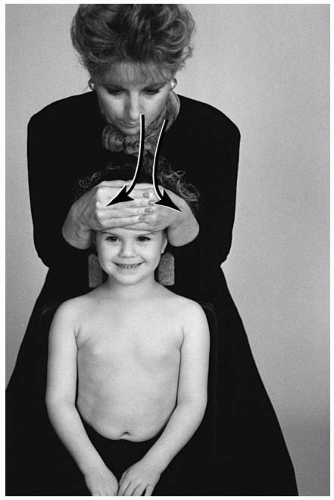

Supine AS Condyle The newborn or infant is placed supine on the pelvic bench. The crown of the head is placed close to the edge of the table. Depending on the arc of thrust necessary for correction, the doctor will squat or kneel directly superior to the infant’s head. Once the condyle block is positioned, the parent can assist by gently holding the child in the supine position. The condyle subluxation without laterality or rotation will be corrected by contacting the glabella with both thenar eminences. The fingers will lightly wrap under the posterior occiput to create a slight lift (

Fig. 5-23). A second hand set-up is the use of the second and third digits from both hands and contacting the glabella, with both thumbs wrapped under the posterior occiput to create a slight lift (

Fig. 5-24). If condyle laterality exists, the doctor will position themselves slightly to the same side of the listing. If the listing is LS the contact hand will be the left and vice versa. The contact will be the soft portion of the doctor’s pisiform on the glabella (

Fig. 5-25). The opposite hand will cup the posterior

occiput and create a slight separation from the atlas. The thrust is an arcing anterior to posterior and slightly superior to inferior movement. Laterality (e.g., PSLS, PSRS) is corrected by the doctor’s contact. To correct condyle rotation, the infant’s head is pre-positioned with slight rotation before the thrust. For posteriority (e.g., PSLSLP, PSRSRP), the head is slightly rotated away from the contact hand (

Fig. 5-26). The anterior listing of PSLSLA or PSRSRA is pre-positioned with slight head rotation toward the side of the doctor’s contact hand (

Fig. 5-27).

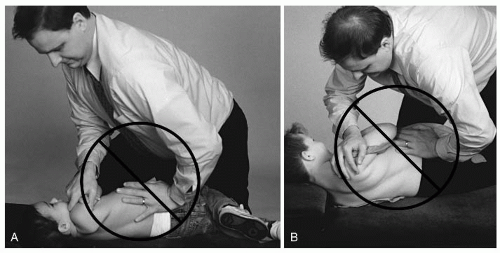

Newborn and Infant

AS Condyle Supine Double Thenar Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Supine AS condyle double thenar adjustment.

Contraindications: All other listings, hypermobility, normal FSU, instability, destruction of the cranium, fracture (pathologic or nonpathologic) of the frontal bone, infection of the contact bone, or fracture of the ocular orbit. Patient Position: Supine at the distal end of the pelvic table. The condyle block is placed underneath the cervical spine to protect the C1-C7 region.

Contact Site: The glabella.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor is kneeling or squatting cephalad to the patient.

Supportive Assistance: The parent holds the upper and lower limbs to keep them from moving.

Pattern of Thrust: Anterior to posterior, superior to inferior with an inferior arcing (scooping) movement across the lateral masses of C1.

Contraindication for the Thrust: The newborn is unable to be maintained in a supine position.

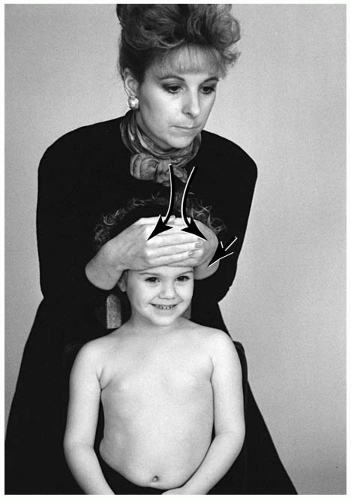

AS Condyle Supine Finger Contact Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Supine AS condyle adjustment.

Patient Position: Supine at the distal end of the pelvic table. The condyle block is placed underneath the cervical spine to protect the C1-C7 region.

Contact Site: The glabella.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor is kneeling or squatting cephalad to the patient.

Pattern of Thrust: Anterior to posterior, superior to inferior with an inferior arcing (scooping) movement across the lateral masses of C1.

ASRS Condyle Supine Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Supine ASRS condyle adjustment.

Patient Position: Supine at the distal end of the pelvic table. The condyle block is placed underneath the cervical spine to protect the C1-C7 region.

Contact Site: The glabella.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor is kneeling or squatting cephalad and to the side of laterality.

Supportive Assistance: The parent keeps the upper and lower limbs from moving.

Pattern of Thrust: Anterior to posterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial with an inferior arcing (scooping) movement across the lateral masses of C1.

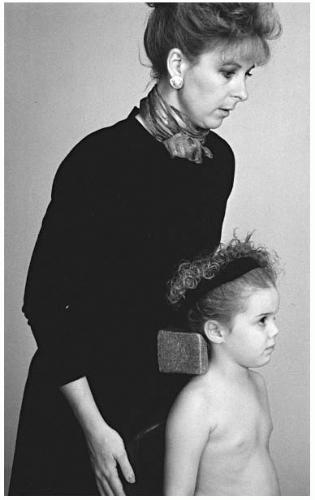

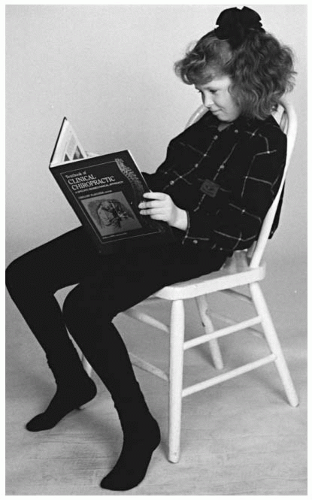

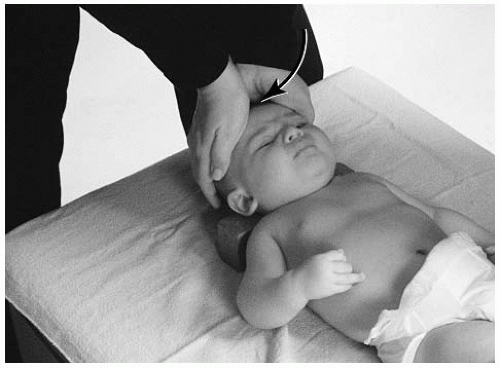

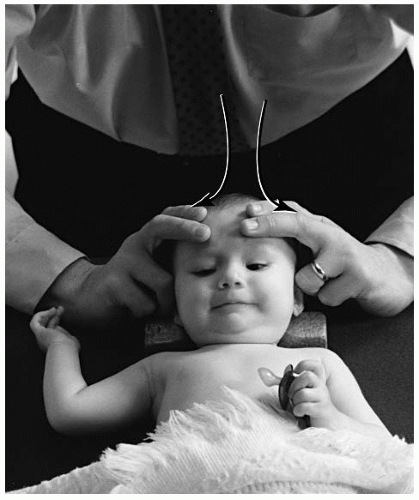

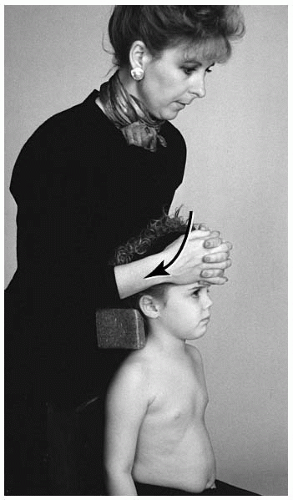

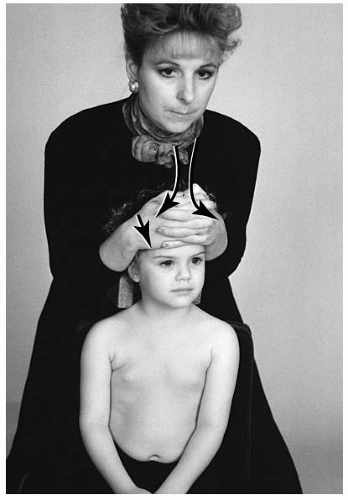

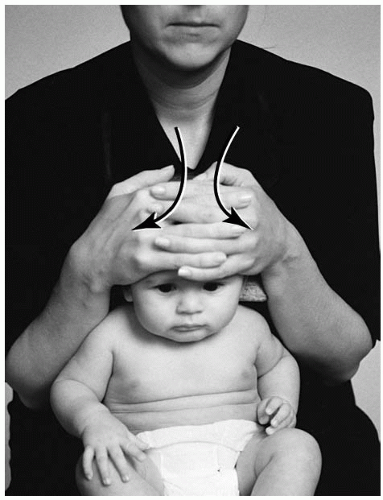

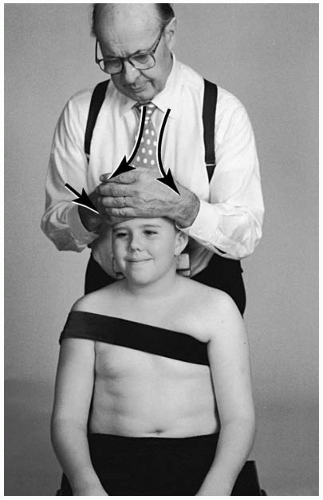

Seated AS Condyle The younger child (e.g., toddler or preschooler) may be positioned on the cervical chair. To accommodate the height of the child, an elevation device (e.g., pelvic bench pillow,

booster chair) may be used on the adjusting chair. The condyle block will be positioned behind C1-C7 and held there with the doctor’s abdomen (

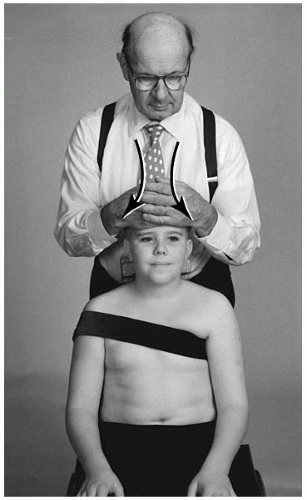

Fig. 5-31). The stabilization strap or the parent’s hand can also be placed on the child’s abdomen and chest to further stabilize the patient. For an AS listing, the flat palm of the doctor’s hand will contact the center of the glabella and supra orbital margin. The opposite hand will overlap the contact hand for stabilization (

Fig. 5-32). An alternative set-up is for the doctor to interlink his or her fingers (

Fig. 5-33). Pre-tension at the joint is obtained with slight head flexion. Before the thrust, the doctor’s elbows should be positioned close to the side of his or her body. This will provide for a smoother glide during the arc of the adjustment. Laterality is corrected by the doctor standing slightly toward the side of listing. The contact hand for a lateral misalignment (e.g., ASRS, ASLS) is the same hand as the side of listing. Condyle rotation (e.g., ASRSRP, ASLSLA) is corrected when the doctor pre-positions the head. For anteriority, the head is slightly rotated to the side of the contact hand (

Fig. 5-34). Posteriority is corrected with slight head rotation away from the contact hand (

Fig. 5-35).

Toddler and Preschooler

AS Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated AS condyle adjustment.

Patient Position: The patient is seated on the cervical chair. The child may need to be raised on the chair (e.g., using a pelvic pillow or booster chair). The condyle block is placed behind the cervical spine to protect the C1-C7 region. The stabilization strap can be used.

Contact Site: The glabella.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands behind the patient supporting the condyle block with his or her abdomen.

Supportive Assistance: The parent can support the upper chest to avoid movement.

Pattern of Thrust: Anterior to posterior, superior to inferior, with an inferior arcing (scooping) movement across the lateral masses of C1.

Contraindication for the Thrust: The toddler or preschooler is unable to be maintained in a seated position.

ASLS Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated ASLS condyle adjustment.

Patient Position: The patient is seated on the cervical chair. The condyle block is placed behind the cervical spine to protect the C1-C7 region. The stabilization strap may be used.

Contact Site: The glabella.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands behind the patient and slightly to the side of laterality. The doctor’s abdomen supports the condyle block.

Pattern of Thrust: Anterior to posterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial, with an inferior arcing (scooping) movement across the lateral masses of C1.

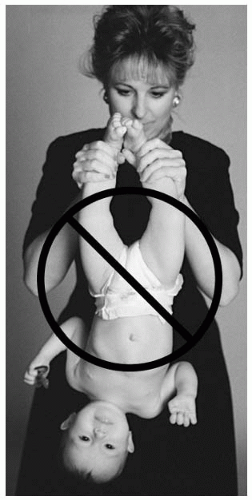

Newborn and Infant

PSLS Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated PSLS condyle adjustment.

Example: PSLS (+θX, +θZ) (

Fig. 5-45) listing.

Contraindications: All other listings, hypermobility, normal FSU, instability, destruction of the condyle fracture (pathologic or nonpathologic) of the condyle bone, infection of the contact bone.

Patient Position: The newborn/infant is placed on the lap of the parent. The involved side is facing the doctor. Contact Site: The left supramastoid groove.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands slightly to the side of laterality.

Supportive Assistance: The parent supports the chest and back region.

Pattern of Thrust: Posterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial, with an inferior arcing movement across the lateral masses of C1.

Contraindication for the Thrust: The newborn is unable to be maintained in a seated position.

PSRS Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated PSRS condyle adjustment.

Example: PSRS (+θX, +θZ) (

Fig. 5-46) listing.

Patient Position: The newborn/infant is placed on the lap of the parent, the involved side facing the doctor.

Contact Site: The right supramastoid groove.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands slightly to the side of laterality.

Supportive Assistance: The parent supports the chest and back region.

Pattern of Thrust: Posterior to anterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial, with an inferior arcing movement across the lateral masses of C1.

Pre-adolescent and Adolescent

PSRS Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated PSRS condyle adjustment.

Example: PSRS (+θX, -θZ) (

Fig. 5-48) listing.

Patient Position: The patient is seated on the cervical chair. The stabilization strap may be used.

Contact Site: The right supramastoid groove.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands behind the patient and slightly to the side of laterality.

Pattern of Thrust: Posterior to anterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial, with an inferior arcing movement across the lateral masses of C1.

PSRSRP Condyle Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated PSRSRP condyle adjustment.

Example: PSRSRP (+θX, -Z, +θY) (

Fig. 5-49) listing.

Patient Position: The patient is seated on the cervical chair. The stabilization strap may be used.

Contact Site: The right supramastoid groove.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands behind the patient and slightly to the side of laterality.

Pattern of Thrust: Posterior to anterior, superior to inferior, lateral to medial, with an inferior arcing movement across the lateral masses of C1.

Atlas (C1-C2)

The atlas subluxation is not as common in the pediatric spine as one might first expect. Compensation in the upper cervical spine, particularly in the coronal plane, can result from a lower cervical subluxation. This is caused by the righting reflex. Examination of the atlas should involve a multiparameter approach. Relying on findings from the radiograph or static palpation alone is not sufficient to determine the need for an adjustment.

Inspection With the patient in a seated position, the doctor may inspect the atlas. If the atlas rotates posteriorly (e.g., ASLP, ASRP), the superficial muscle groups can bulge on the side of posteriority. The atlas that has rotated anteriorly (e.g., ASRA, ASLA) can present with a slight ipsilateral head tilt. To confirm lateral flexion malposition, request the patient to shut his or her eyes and then flex and extend his or her head for a few seconds. If lateral flexion fixation is present there may be a slight head tilt during the procedure or after resting in a neutral position.

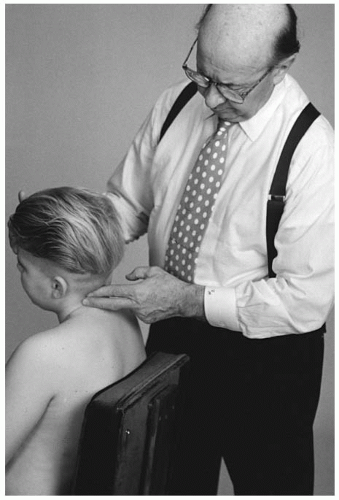

Static Palpation Static palpation should be performed in the sitting position. The newborn or infant can be seated on the parent’s lap; the parent’s hands can support the chest and back of the child. The older child may be examined independently on a chair. The distal end of the fifth digit or the index digit is used to palpate the musculature. The static musculature examination is used to detect tissue edema or bogginess. The edema reaction at the tissues may be a response caused by autonomic nervous system dysfunction or trauma to the region. If posterior rotation is present, a bulging or increased musculature will be palpated. The examiner should be aware that muscular asymmetry or skeletal malformation can influence the validity of these examination findings.

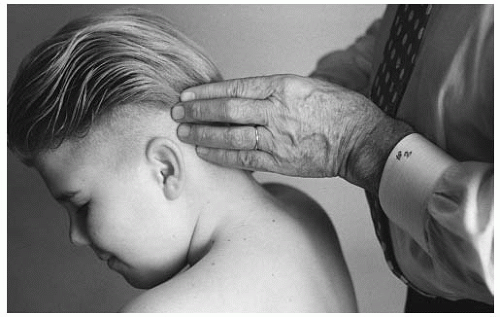

Motion Palpation Motion palpation is conducted in the sitting position. As with static palpation, the parent may assist in the stabilization process of the smaller child or infant. The analysis of the atlas is to determine if fixation dysfunction is present in relationship to the axis (C2). The rotation and lateral flexion position of the atlas is ascertained with this procedure. The AS or AI component of the listing can be determined from the lateral radiograph.

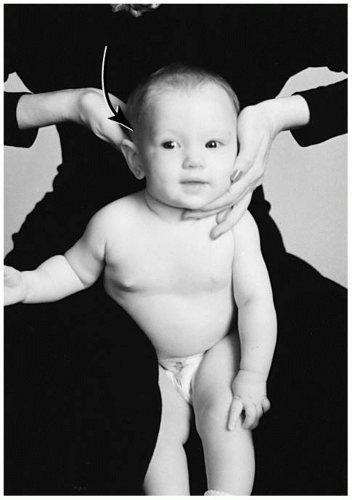

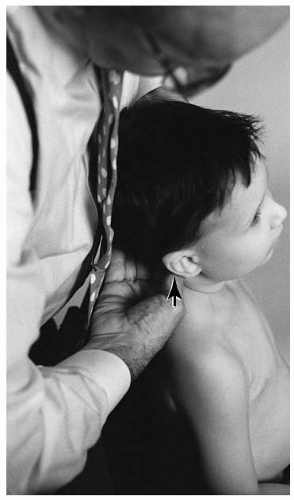

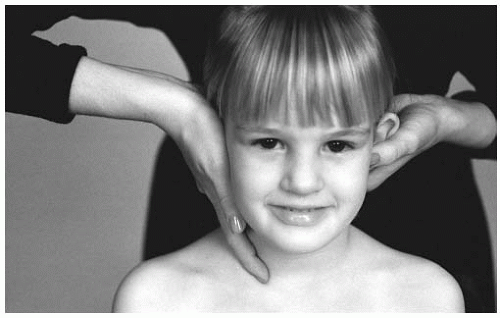

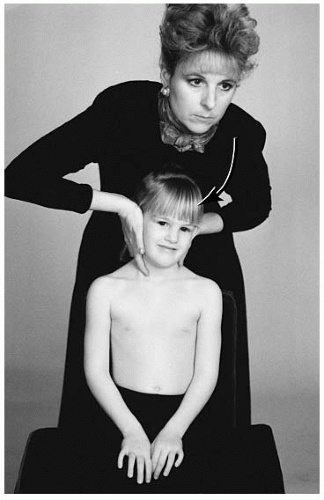

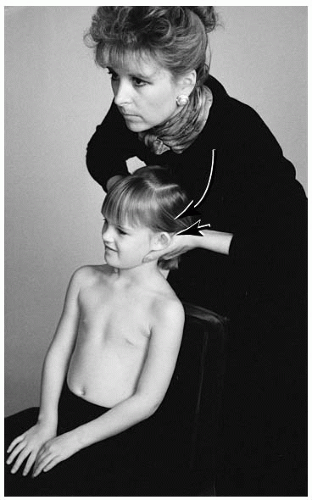

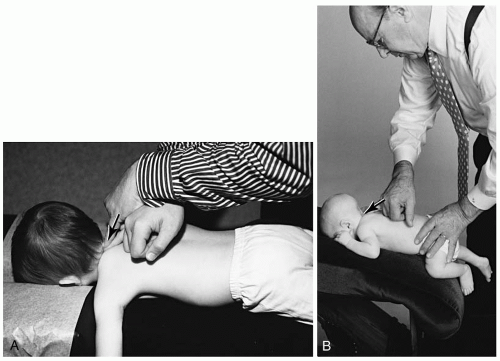

To determine lateral flexion (±θZ), the doctor will need to contact bilaterally the transverse process of the atlas. The younger child can be contacted with the distal end of the fifth digit and thumb (

Fig. 5-50 A,B). The larger child will be contacted with the second digit and thumb. The doctor should confirm the findings by reversing the palpation contact hand. This will reduce hand bias. With the doctor’s stabilization hand on the crown of the head, the doctor will laterally flex the head from side to side. Although the motion is not completely understood, it seems that the side contralateral to the fixation reveals the loss of motion. This appears as the lateral mass of C1 raised on the contralateral side when C1 is laterally flexed onto C2 (

39). The listing is confirmed with the APOM radiograph. The lettering assigned is “R” for right or “L” for left after the AS (e.g., ASR, ASL) or AI (e.g., AIR, AIL).

The primary movement of the atlas-axis relationship is Y-axis rotation. Rotation (Y axis) can be determined very readily with motion palpation. First, place the distal end of the fifth or second digit at the anterior-lateral aspect of the transverse process of the atlas. Next, slowly rotate the head from side to side. The side of rotational fixation will reveal restriction.

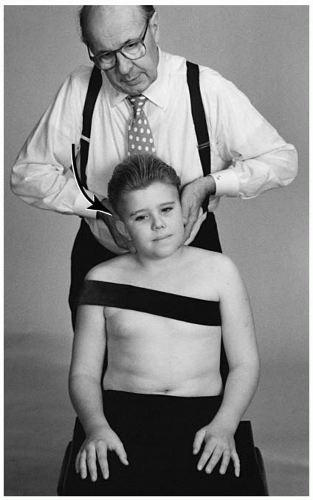

On the older child, Dvorak’s maneuver can assist in determining if an upper cervical (C1-C2) rotational fixation is present. Flex the child’s head and rotate the spine from side to side (

Fig. 5-51). The side of fixation will reveal restriction of motion. Once the side of laterality (±θZ) has been determined, rotation, if it exists,

must be determined. A posteriorly rotated atlas will be confirmed when the doctor can demonstrate restriction of that movement. A left posterior atlas (e.g., ASLP) will reveal restricted range of motion when the doctor rotates the patient’s head to the right. Likewise, a clockwise (+θ) restriction of the atlas reveals right posteriority (e.g., ASRP). The left anterior atlas (e.g., ASLA) is determined when the range of motion clockwise is restricted upon rotation. The ASRA listing is concluded when counterclockwise motion is diminished. The anterior “A” listing is often more difficult to determine.

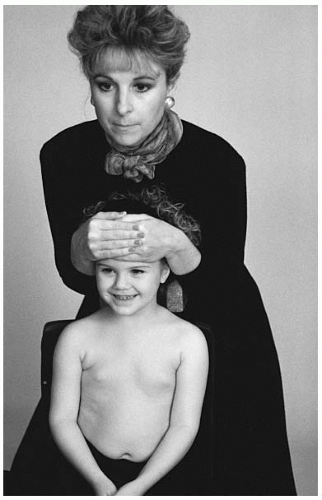

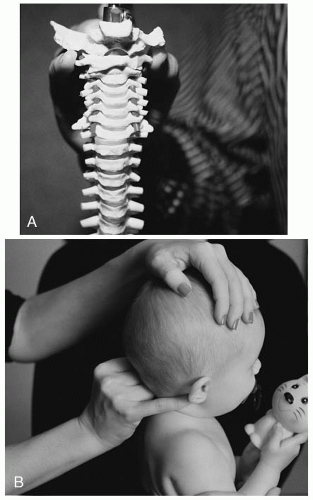

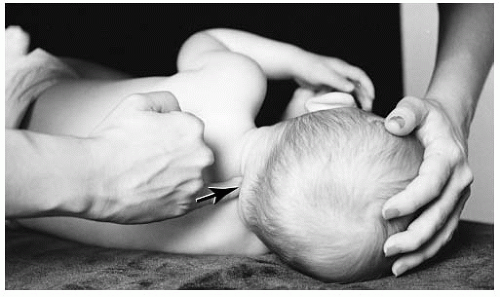

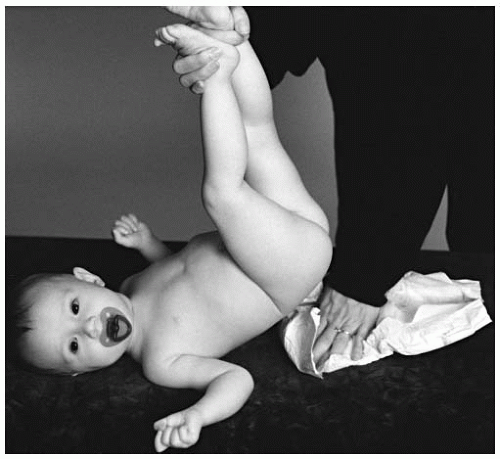

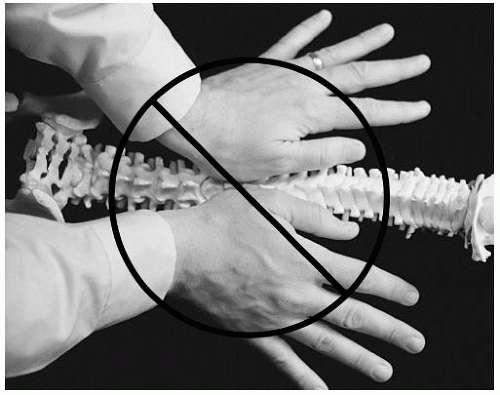

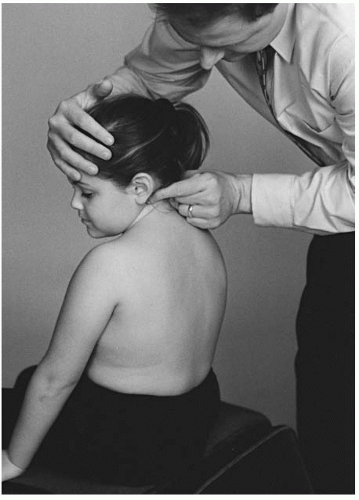

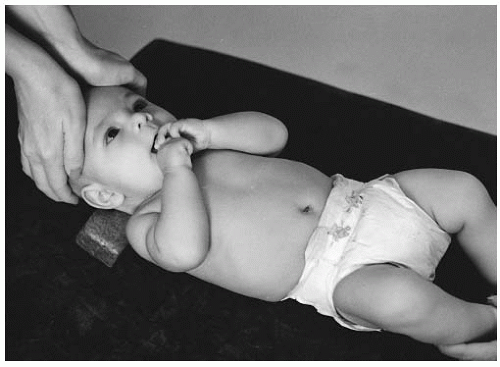

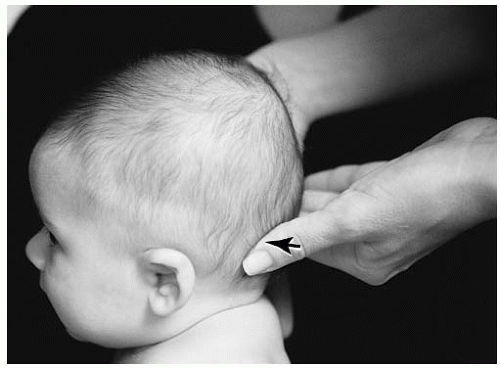

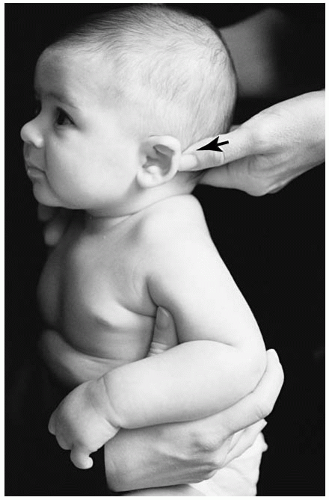

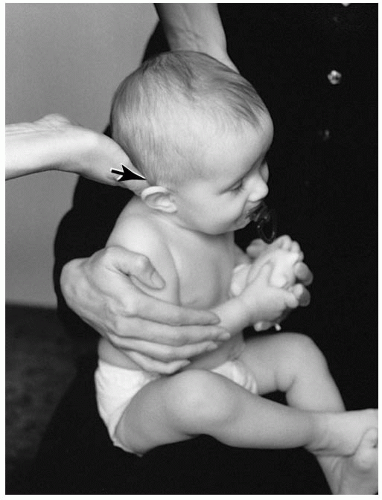

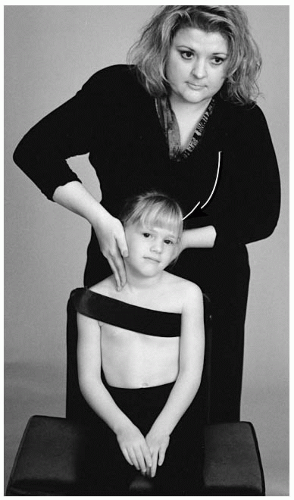

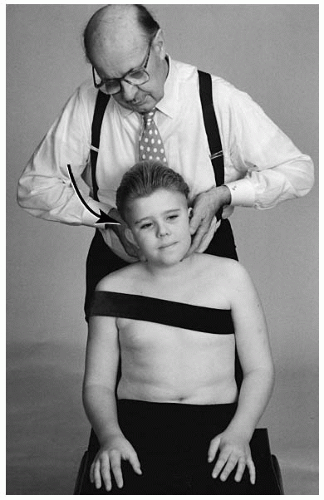

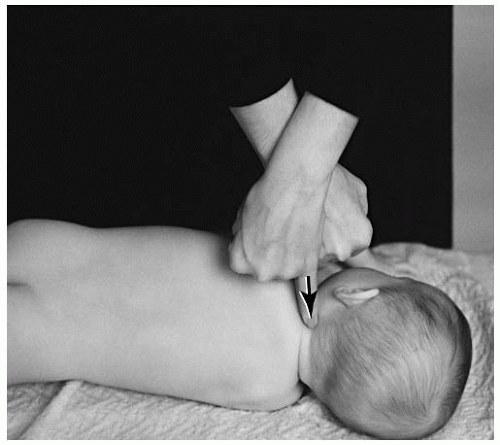

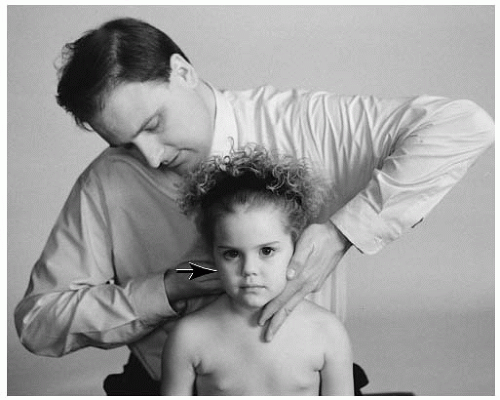

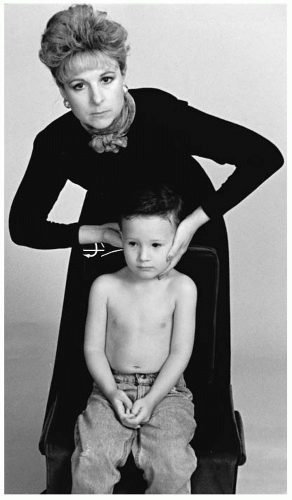

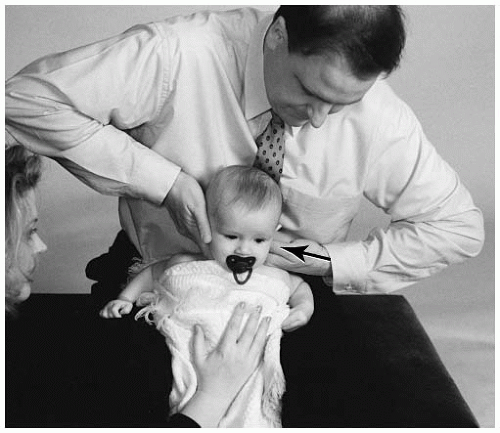

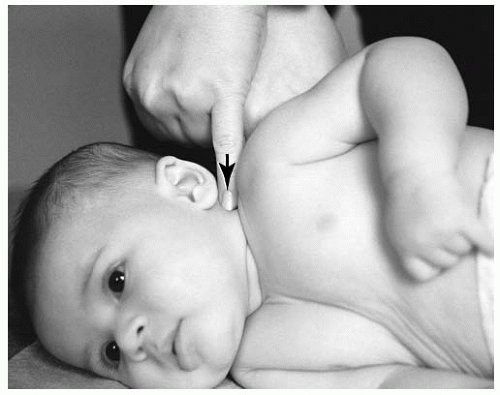

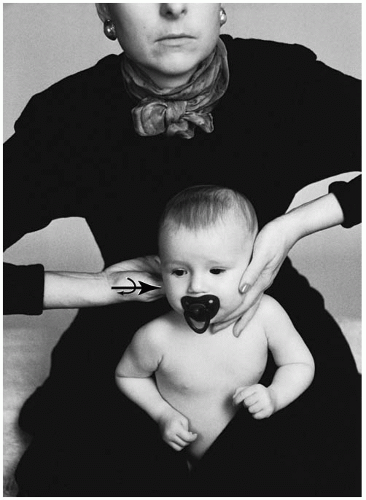

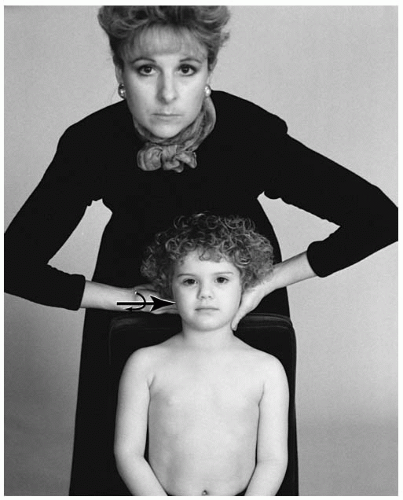

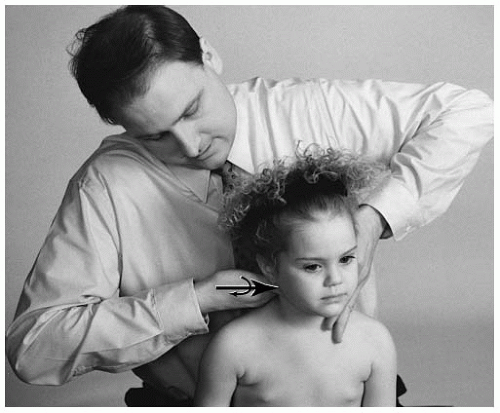

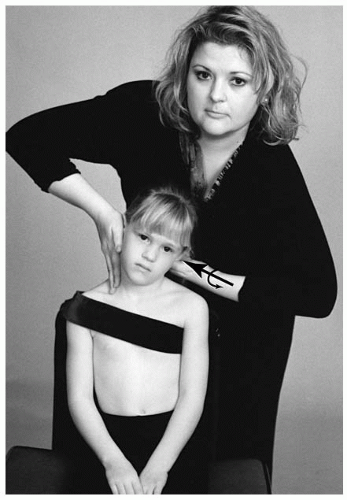

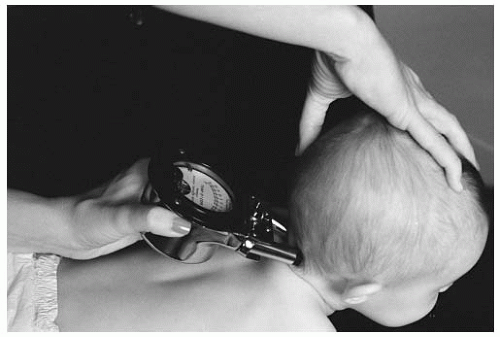

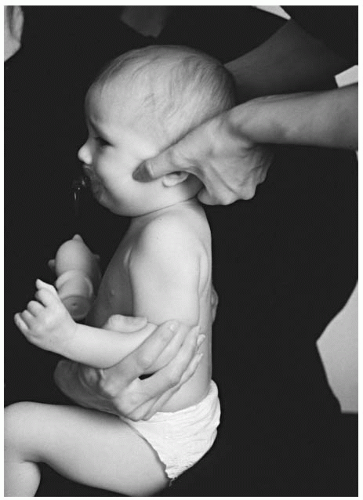

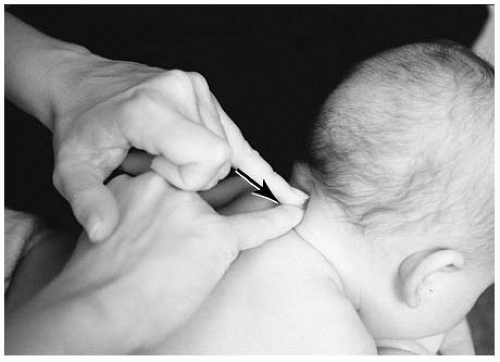

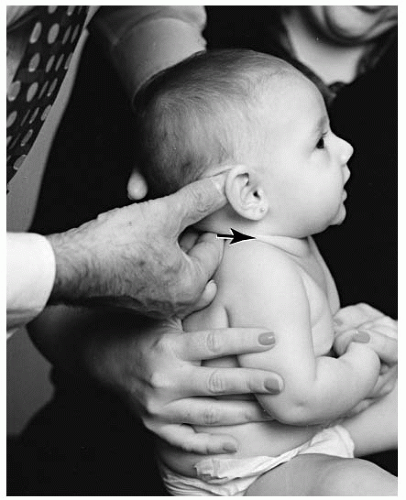

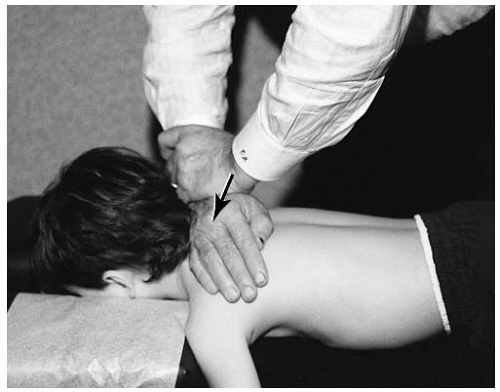

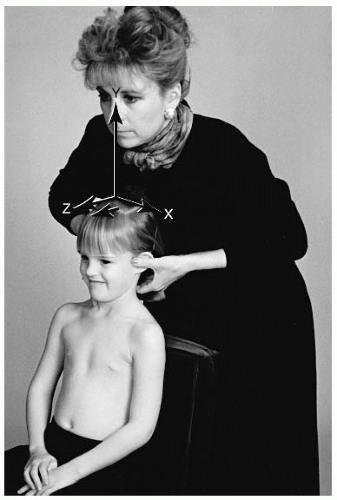

Instrumentation The newborn and infant are typically more difficult to assess with an instrument (e.g., Nervoscope, Temp-o-scope) than the older pediatric patient. What is commonly referred to as “baby fat,” or the brown fatty tissue present, can interfere with the gliding procedure (

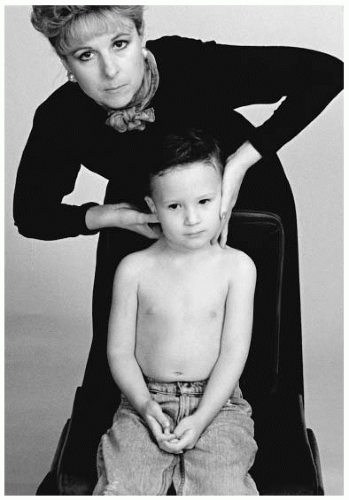

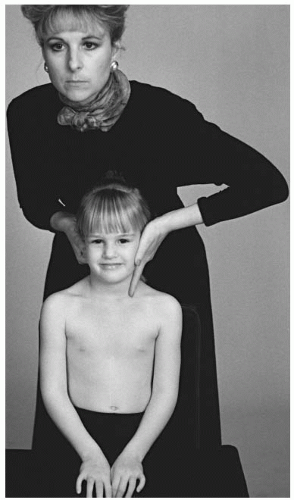

Fig. 5-52). With the toddler, the doctor must be careful to take into account that the child may move during the procedure, which leads to an inaccurate reading. Stabilization is required to maintain the subject in a motionless, neutral position (

Fig. 5-53).

The procedure for this examination is to glide the instrument from caudad to cephalad. Suboccipital hair is also another factor that may give a false positive finding. If a true positive finding does occur, the doctor must further determine through other examination methods if the reading reflects a C1 or C2 involvement due to the proximity of the articulations.

Radiographic Analysis When analyzing the atlas, it is important to acknowledge the possible active involvement of adjacent segments in compensation. The primary biomechanical motion of the atlas is rotation around the odontoid process of the axis. Therefore, the odontoid process is used as a reference point in the analysis of the atlas.

The lateral cervical radiograph is analyzed to determine the relationship between C1 and C2 (see

Chapter 4). The odontoid will be divided with two dots. The first dot is placed at the base and center of the odontoid, the second dot at the center and superior aspect of the odontoid. Draw a longitudinal line intersecting the two points. This line is called the odontoid line. Through the mid-section of the body of the axis, draw a line perpendicular to the odontoid line. This line is referred to as the OPL.

To analyze the atlas, place one dot in the middle of the anterior tubercle, and a second dot at the middle junction of the posterior tubercle and the posterior arch. The line drawn between the two points is called the AP atlas plane line. Occasionally the lateral radiograph will reveal the atlas in a lateral flexion position. This will project a space between the posterior arch (rather than an overlap). In this case, bisect the space that the lateral atlas tilt creates. If the AP line and the OPL are parallel, a normal atlas and axis relationship can be assumed. Slight atlas extension onto the axis can also be considered to be within normal limits.

To evaluate the coronal plane posture, an open mouth projection is analyzed. The axis line is drawn parallel at the superior aspect of the body of axis, referred to as the “axis plane line (APL).” The APL represents the horizontal plane of atlas. To draw the line, choose two like points on the atlas. A reliable anatomical point is the transverse process-lateral mass junction. Often the superior border of the transverse process is obstructed by overhanging of the occiput. If this is the case then the dot should be placed on the inferior transverse process where it intersects the lateral mass. The two dots are connected with a line. A normal atlas-axis relationship is present when the atlas plane line and the APL appear parallel.

Anteriority (+Z) The atlas may slightly slide anteriorward as it rotates around the X axis. The transverse ligament is responsible for the close relationship of the atlas to the axis. Rupture or severe stretching of the transverse ligament should be suspected if noticeable anterior slippage is viewed on the lateral radiograph. The contact point for the adjustment for the atlas is the antero-lateral portion of the transverse process.

Superiority/Inferiority (±θX) The anterior tubercle can be referenced for the superiority or inferiority of the atlas on the lateral radiograph. Superiority or hyperextension positional dyskinesia is more common than inferiority/hyperflexion displacement. The superiority (-θX) misalignment is detected when the AP atlas plane line and the OPL diverge anteriorly. Inferiority, which is rare, can be detected when the AP atlas plane line and the OPL coverage anteriorly. The superior displacement is labeled “S” and follows the A listing. The inferior misalignment is given the letter of “I” and also follows the letter A. The listing of the atlas is AS or AI.

A second radiographic finding that can confirm the line analysis is to observe the space between the anterior portion of the dens and the posterior portion of the anterior tubercle of the atlas. When the AS listing is present this space will reveal an inverted “V,” the AI listing will appear as a “V.” It should be noted that the younger pediatric patient may show a marked space difference between the dens and tubercle. This increased atlas dens interspace (ADI) should not be interpreted as severe AS or AI misalignment. The normal ADI measurement of the pediatric spine is 1 to 5 mm. A greater measurement may be an indication of transverse ligament instability (e.g., a tear or sprain) or ligament absence, as seen in 25% of Down’s patients (

14,

40).

Laterality ±θZ (±X) The atlas can rotate around the Z axis and move toward the convexity of lateral bend (termed laterality). The AP radiograph is used to establish laterality. On the side of laterality, the atlas transverse plane will appear with a superior lift of the atlas from the axis plane line. The two possible listings of laterality are ASR or ASL. The ASR listing would reflect the divergence of the two lines on the right side.

Rotation +θY The AP radiograph is used to determine the fourth letter of the atlas listing (

Table 5.3), which is the Y-axis rotational component. The anatomical reference points to determine rotation are the lateral masses of atlas. Rotation is listed on the side of atlas laterality (±θZ); if the atlas rotates posteriorly, the lateral mass will appear smaller. Anterior rotation of the atlas appears as a larger width of the lateral mass on the side of laterality. The possible listings are ASRP, ASLP, ASRA, and ASLA.

The indented concave surfaces of the lateral masses can be analyzed on the AP radiograph. Rotation can be analyzed by locating the radiolucency of the concave and indented upper medial surfaces of the lateral masses. The side of posterior rotation will manifest a narrower radiolucency and the anterior rotation will have a wider appearance.

A third method of analyzing the radiograph for rotation is by comparing the occiput-atlas relationship. The transverse occiput line may descend on the side of atlas anteriority. This may appear as a convergence of the transverse occiput line toward the atlas plane line.

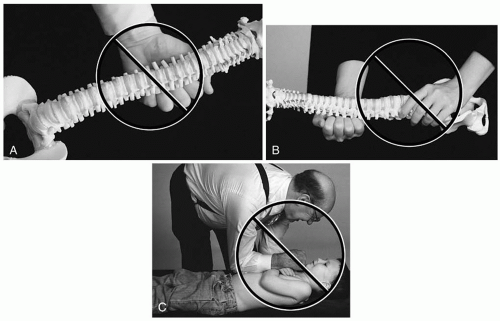

C1-C2 Adjustment

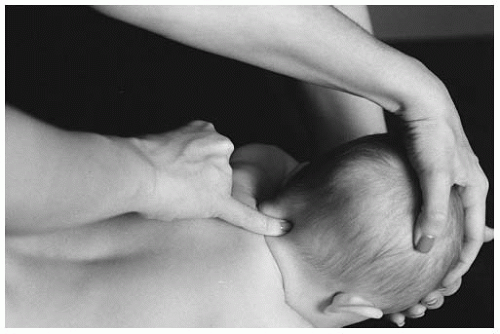

The atlas adjustment is adapted to the age and compatibility of the pediatric patient. The neonate and the infant should be adjusted in a side posture or seated position. For the side posture set-up, the patient should be placed across the lap of the parent or on the pelvic table. If the patient is placed on the pelvic table, the doctor should evaluate the space between the lateral cervical spine and the table. A space >1/4A in. should be reduced by the placement of a folded towel or supportive foam to prevent this space from causing an uncontrolled drop phenomenon during the thrust (acceleration) phase.

The neonate or infant should be placed with the atlas listing-involved side up (e.g., ASR or ASL), the head and body in a neutral position, and the face toward the doctor. The practitioner should stand facing the patient. To eliminate the antero-lateral component of the listing (e.g., ASR or ASL) contact is made at the antero-lateral aspect of the transverse process of the atlas. The contact is made using the distal end of the fifth or second digit (

Fig. 5-54). The distal stabilization digit (e.g., fifth or second) contacts the nail bed of the contact digit. The doctor’s forearms and stance should reflect the line of correction. To correct the posterior (“P”) component,

the doctor’s stance should be slightly leaning forward toward the patient. For the anterior (“A”) listing, the doctor’s stance should be slightly leaning away from the patient. The parent may assist by stabilizing the infant’s head and body.

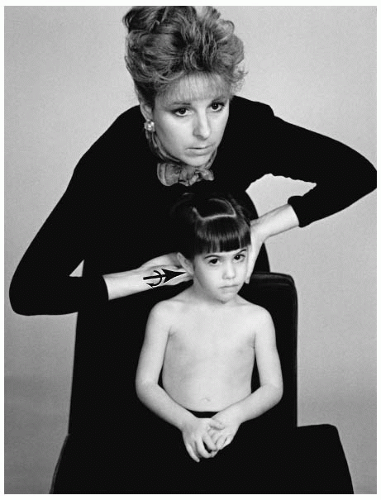

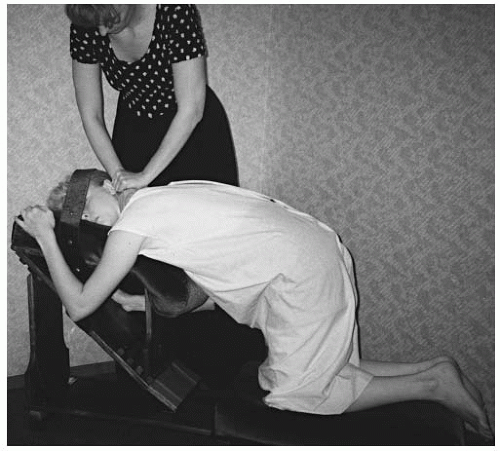

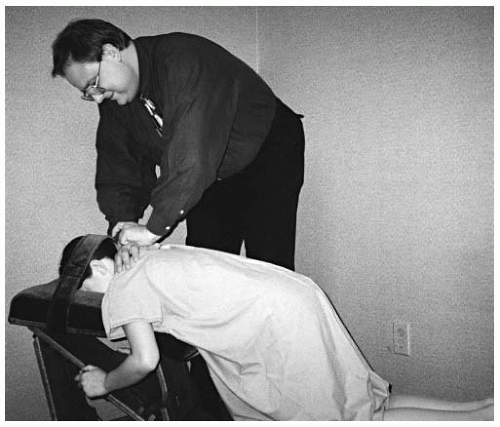

The sitting position is ideal for the infant or toddler. There are several possible sitting positions. The infant/toddler may be placed on the lap of an attending parent (

Fig. 5-55). The parent should stabilize the child’s chest and mid-thoracic spine. The side of laterality should be placed toward the doctor for set-up. A taller doctor may place the infant/toddler between his or her legs and apply slight thigh pressure for stabilization (

Fig. 5-56). This procedure should only be chosen if the doctor can maintain their contact and stabilization arms in proper alignment.

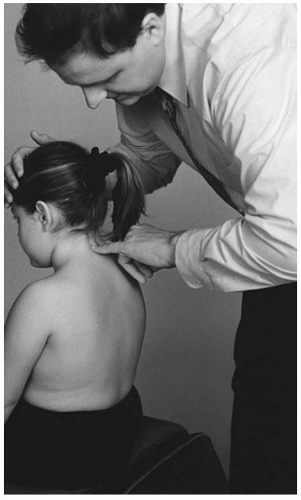

The toddler or older child may sit independently in a cervical chair with a back support. The stabilization strap or the parent’s hands are used to stabilize the chest. On the side of atlas laterality, the doctor will contact the antero-lateral aspect of the transverse of the atlas (e.g., ASR or ASL) with the distal portion of the thumb (

Fig. 5-57). The rotational aspect of the listing (e.g., ASRP, ASRA, ASLP, ASLA) can be corrected by slightly rotating the head before the thrust. The posterior atlas (e.g., ASRP or ASLP) is corrected by turning the head away from the contact hand (

Fig. 5-58). Anterior rotation (e.g., ASRA or ASLA) is corrected by rotating the head slightly toward the contact hand of the doctor. The opposite hand will be used to stabilize the opposite side of atlas laterality (

Fig. 5-59). The stabilization hand will cup the ear and the fingers will point caudally to protect the C2-C3 articulation. The stabilization hand should not be used to create a counterforce. The thrust is given with a slight torque (+θX) to enhance the fluidity of the adjustment. A “set and hold” follows at the end of the adjustment.

Newborn and Infant

CI ASL Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated atlas adjustment.

Example: ASL (+Z, -θX, +θZ, +X) (

Fig. 5-60) listing. AS (-θX) lateral flexion to the right (+θZ). Flexion and left lateral flexion fixation dysfunction.

Contraindications: All other listings, hypermobility, normal FSU, instability, pathologic fracture of the neural arch, infection of the neural arch or transverse process, destruction of the atlas, transverse ligament rupture.

Patient Position: The newborn/infant is placed in between the thighs of the seated doctor. The doctor applies slight thigh pressure.

Contact Site: Antero-lateral aspect of the transverse process of the atlas.

Supportive Assistance: The parent should keep the torso from moving.

Pattern of Thrust: Lateral to medial, with an inferior arc toward the end of the thrust.

Contraindication for the Thrust: The newborn/infant is unable to be maintained in a seated position.

CI ASL Side Posture Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Side posture atlas adjustment.

Example: ASL (+Z, -θX, +θZ, +X) (

Fig. 5-61) listing. AS (-θX) lateral flexion to the right (+θZ). Flexion and left lateral flexion fixation dysfunction.

Patient Position: The newborn/infant is placed on his or her right side on the pelvic bench. The head piece of the hi-lo or knee-chest table or the lap of the parent may be used. A small, rolled up towel or foam may need to be placed between the patient’s lateral aspect of the cervical spine and table to reduce any air gap.

Contact Site: Antero-lateral aspect of the transverse process of the atlas.

Supportive Assistance: The parent may need to stabilize the chest and/or lower limbs from activity.

Pattern of Thrust: Lateral to medial, with an inferior arc toward the end of the thrust.

Contraindication for the Thrust: The newborn/infant is unable to be maintained in a side posture position.

CI ASRA Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated atlas adjustment.

Example listing: ASRA (+Z, -θX, -θZ, -X, +θY) (

Fig. 5-62).

AS (-θX) lateral flexion to the left. Flexion and left lateral flexion, as well as right axial rotation fixation dysfunction.

Patient Position: The newborn/infant is placed in a seated position in the doctor’s lap. The doctor applies slight thigh pressure.

Contact Site: Antero-lateral aspect of the right transverse process of the atlas.

Pattern of Thrust: Lateral to medial, with an inferior arc toward the end of the thrust.

Toddler and Preschooler

CI ASR Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated atlas adjustment.

Example: ASR (+Z, -θX, -θZ, -X) (

Fig. 5-63) listing. AS

(-θX) lateral flexion to the right (+θZ). Flexion and right

lateral flexion fixation dysfunction.

Patient Position: The toddler/preschooler is placed on

the cervical chair.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor stands behind and slightly to the side of laterality.

Contact Site: Antero-lateral aspect of the right transverse process of the atlas.

Supportive Assistance: The stabilization strap or the parent should keep the torso from movement.

Pattern of Thrust: Lateral to medial, with an inferior arc toward the end of the thrust.

CI ASRP Seated Adjustment

Name of Technique: Gonstead.

Technique Procedure: Seated atlas adjustment.

Example listings: ASRP (+Z, -θX, -θZ, -X, -θY) (

Fig. 5-64).

AS lateral flexion to the left and right axial rotation.

Patient Position: The toddler/preschooler is seated between the thighs of the doctor.

Doctor’s Position: The doctor is seated on the pelvic bench or cervical chair.

Contact Site: Antero-lateral aspect of the right transverse process of the atlas.

Supportive Assistance: The stabilization strap may be used or a parent can stabilize the torso.

Pattern of Thrust: Lateral to medial, with an inferior arc toward the end of the thrust.