Introduction

Obesity continues to rise in prevalence around the globe and in the United States, now affects as many as 1 in 3 pregnancies delivered [1]. While the roots of the epidemic remain elusive, the consequences are becoming clearer. The medical implications of obesity outside pregnancy are well known, including hypertension and cardiovascular disease, joint disease, thromboembolism, dislipidemia and diabetes [2,3]. The ramifications of gravid obesity such as diabetes, hypertension and pre-eclampsia, fetal overgrowth and neonatal obesity, prolonged labor, cesarean delivery and surgical complications, are similarly far-reaching, with important implications for maternal health and fetal well-being [4,5]. The impact on the routine practice of prenatal care is significant, spanning from before conception through the postpartum period, leaving few obese patients unscathed. In the end, the challenges to the physician charged with caring for the obese gravida may be twofold. First, care must take into account the various increases in health risk to mother and child. Modifications in prenatal care and delivery may be dictated by maternal size at conception or excessive pregnancy weight gain. Second, pregnancy may also represent an opportunity for intervention, and an effort to break the cycle of obesity.

The World Health Organization (WHO and National Institutes of Health (NIH) define “normal weight” by the Body Mass Index (BMI, calculated as weight in kg divided by the height in meters squared). Normal BMI is 18.5–24.9, overweight is BMI 25–29.9 and obesity is BMI ≥30 (Table 27.1). Obesity can be further characterized by BMI as class I (30–34.9), class II (35–39.9) and class III (≥40) [6].

Table 27.1 WHO body habitus categories

| BMI | Category |

| <18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

| 25.0–29.9 | Overweight |

| ≥30.0 | Obese |

The global epidemic of obesity continues to grow at an alarming rate, crossing boundaries of age, race and gender (Table 27.2). Indeed, it is now so common that it is replacing the more traditional public healthcare concerns including undernutrition and infectious disease as one of the most significant contributors to ill health [6].

Table 27.2 Increase in adult obesity 1994–2000

| 2000 | 1994–98 | |

| Obese | 30.4% | 22.9% |

| Overweight | 64.5% | 55.9% |

The prevalence of adult obesity in the United States, defined as a BMI >30, rose to an alarming 30.5% in 2000, compared with 22.9% from 1994 to 1998. The proportion of the population meeting the definition of overweight (BMI >25) increased from 55.9% to 64.5% during the same period. Of particular concern is the rise of obesity among teens, with the prevalence of obesity in adolescents in the USA increasing by 11.3% between 1994 and 2000 [7]. The risk of increasing obesity is disproportionate among the races in the US and other countries, with the prevalence of obesity in the US increasing most among African American women [4].

Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy

Obesity appears to be associated with a wide range of increased risks to the mother and the pregnancy and a detailed discussion of the literature on these risk associations is beyond the scope of this chapter. They are listed in Box 27.1 and discussed in detail in the associated references. What follows is a discussion of some of the more important known associations.

Obesity and the risk of cesarean delivery

Retrospective data describe the rate of cesarean delivery among overweight and obese women to be as high as 50% [4,9,10], applying to both the primary cesarean delivery [9] (Table 27.3) and the failure to successfully deliver vaginally after a previous cesarean [10] (Table 27.4). The etiology of this finding is likely to be multifactorial, including the influence of fetal macrosomia, maternal size, and other factors not yet described. There is no satisfactory single explanation as to the mechanism behind the failure to deliver vaginally in the obese. Chauhan et al. reported that 46% of obese women failing a trial of labor after cesarean to have an arrest disorder [11]. In a cohort studied by Edwards et al., 39% of obese women were delivered by cesarean after labor dystocia, 29% due to nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracings, 10% due to malpresentation, and 8% secondary to failed induction [12].

Table 27.3 Odds of cesarean with increasing maternal BMI

Reproduced from Flegal et al. [8].

| BMI (kg/m2) | Odds ratio |

| <19.8 | 0.71 (0.4–1.24) |

| 25.2–30 | 1.64 (1.09–2.47) |

| >30 | 2.5 (1.68–3.71) |

Table 27.4 Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) success rates as affected by maternal body habitus

Reproduced from Ehrenberg et al. [9].

| BMI (kg/m2) | % VBAC | P value |

| <19.8 | 84.7% | 0.04 |

| 19.8–25 | 70.5% | – |

| 25–30 | 65.5% | 0.35 |

| >30 | 54.6% | 0.003 |

Box 27.1 Conditions seen with increased frequency in obese pregnant patients [57,58]

Preconception

- Subfertility

Antepartum

- Miscarriage

- Gestational diabetes

- Pre-eclampsia

- Congenital anomalies including orofacial, cardiac and neural tube defects

- Difficulty in obtaining detailed images with ultrasound

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Fetal macrosomia

Intrapartum

- Prolonged labor

- Shoulder dystocia

- Difficulty with endotracheal intubation for general anesthesia

- Difficulty with placement of spinal or epidural catheter for regional anesthesia

- Special equipment needs (labor and OR beds, stretchers, wheelchairs)

- Cesarean delivery

- Post-term pregnancy

Postpartum

- Postpartum hemorrhage

- Wound infections and breakdown

- Endometritis

- Venous thromboembolism

- Increased weight in offspring

- Increased risk of childhood obesity

- Possible difficulty with breastfeeding

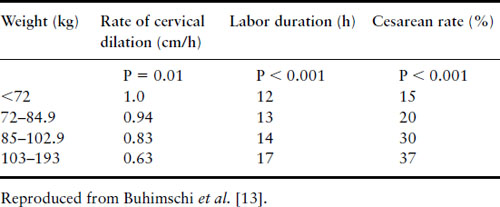

In searching for the root cause of such findings, basic obstetrics relies on describing the power of contractions, the size and composition of the fetus (passenger), and the pelvis. The amount of power generated by the uterus in the obese and nonobese laboring woman is equivalent [13] and the degree of neonatal macrosomia alone cannot completely explain the elevated risk of cesareans in the obese [9]. The contribution of maternal pelvic fat to the failure of a trial of labor in the obese parturient has not yet been evaluated. Such a “soft tissue dystocia” may explain not only the increased rate of cesarean delivery, but also the prolongation of various stages of labor that has been described (Table 27.5) [14].

Table 27.5 Perturbations of labor in nulliparous women as influenced by maternal weight at delivery

Once the need for abdominal delivery has been declared, the risk of complications continues. Postoperative complications include wound infections and breakdown, endomyometritis, venous thromboembolism, febrile hospital stay and delayed return to productivity [15–18].

Skin incision choice

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree