Somatic Growth and Development

Charles E. Irwin Jr.

Adolescence comprises a period in the life cycle between childhood and adulthood. Biological, psychological, social, environmental, and legal changes influence the definitive onset and termination of adolescence. Pubescence is often described as the onset of adolescence; however, the mean age of onset of puberty in girls in the United States varies by race and is earlier than in previous generations. The mean age of onset for white girls is 9.7 years with a range of onset from 7.8 to 11.6 years; and for black girls, 8.1 years with a range of onset from 6.1 to 10.1 years. In boys, the onset of puberty has remained stable at 11.4 years of age with a range of 9.5 to 13.51-6 (see Chapter 540). For purposes of discussion in this section, adolescence in chronologic years is defined as the period from 10 to 21 years.

All bodily tissues are affected by the biological changes of puberty. Growth of the reproductive, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems is closely correlated during this period. The major biological changes occurring during puberty can be classified into 6 groups: skeletal growth, alterations in body composition, cardiorespiratory changes, hematologic development, neuroendocrine development, and reproductive maturation. Chronologic age does not always correlate with biological maturity. Sexual maturation rating (SMR) stages, as originally described by Tanner and Marshall, provide a more accurate assessment of the biological developmental stage of the adolescent (see Chapter 540).7,8

SKELETAL GROWTH

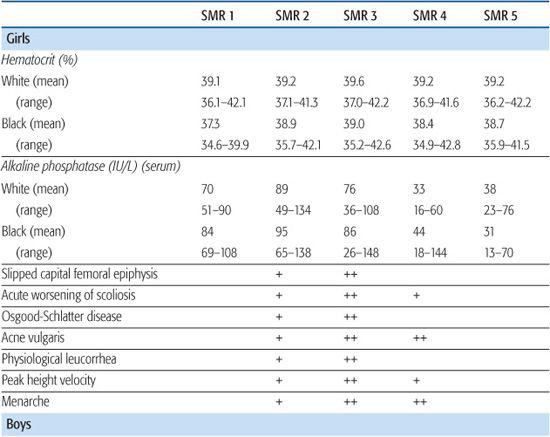

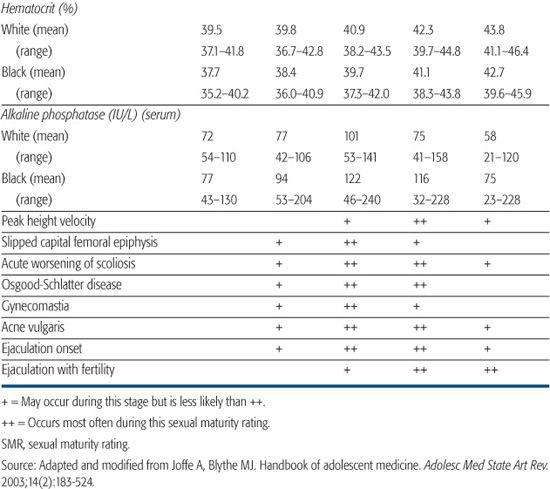

The secondary growth spurt at pubescence accounts for approximately 25% of final adult height.9 As outlined in Table 63-1,10 the growth spurt for girls occurs at an earlier sexual maturity rating (SMR 2–3) than for boys (SMR 4). Girls reach a final mean adult height of 163.8 cm at a mean age of 16 years compared with 176.8 cm for boys at a mean age of 18 years. Assessment of skeletal growth during adolescence is done through the use of a height-velocity curve with consideration of the gender-specific sexual maturity rating. Bone age can be determined through the use of a hand roentgenogram.11

ALTERATIONS IN BODY COMPOSITION

Significant body composition changes occur during adolescence. Weight gain peaks during the growth spurt and accounts for over 40% of the ideal body weight. Weight gain differs by gender, with lean body mass increasing in boys from 80% to 90% and decreasing in girls from 80% to 75%. The mean body fat in girls increases throughout puberty from 15.7% to 26.7%. The mean body fat in boys increases from 4.3% to 11.2% early in puberty (usually SMR 1–2) and remains constant through adulthood. Girls characteristically have more subcutaneous adipose tissue in the pelvic, breast, upper back, and arm areas. Shortly after the growth spurt is completed, muscle mass peaks: for girls at SMR 3 to SMR 4 and for boys at SMR 5. This increase in muscle mass can be measured by monitoring increases in creatinine excretion.10

HEMATOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT

Blood volume, red blood cell mass, and hematocrit increase throughout pubescence in boys (Table 63-1). These same parameters remain relatively constant for girls.

CARDIORESPIRATORY CHANGES

There are significant changes within the cardiovascular system during adolescence: The weight of the heart doubles, and systolic blood pressure increases for boys and plateaus in girls. The decreased heart rate seen in late childhood stabilizes in adolescence after growth of the heart. Within the respiratory system, the lung size increases with a parallel drop in respiratory rate and a significant increase in vital capacity.

Table 63-1. Clinical Correlates of Pubertal Maturation

NEUROENDOCRINE DEVELOPMENT

Over the past decade, there have been significant insights into changes within the central nervous system.12-14 Magnetic resonance imaging has demonstrated a general pattern of childhood peaks of gray matter followed by adolescent declines, functional and structural increases in connectivity and integrative processing, and changing balance between limbic/subcortical and frontal lobe functions, which extends well into young adulthood. These recently described changes may account for the delayed onset of executive functioning in most adolescents until they reach early adulthood.14

The neuroendocrinologic control of puberty through the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is discussed in detail in Chapters 540 and 541.

MATURATION OF THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM: OVERVIEW

The maturation of the reproductive system and the appearance of the secondary sex characteristics are definitive changes unique to puberty (see Chapters 64 and 65). The sexual maturity ratings of Marshall and Tanner provide a classification to monitor the normal events of puberty from prepubertal (SMR 1) to adult (SMR 5). The ratings for girls are based on breast (B1–B5) and pubic hair (P1–P5) development. The ratings for boys are based on pubic hair (P1–P5) and genitalia (G1–G5) development.

Visible sexual maturation in the girl usually begins with thelarche between 6.1 and 11.6 years. The mean age of menarche in the United States is 12.7 years (at SMR 3 or 4) with a normal range of 10 to 16.5 years. The average duration of puberty for girls is 4 years with a range of 1.5 to 8 years. Visible sexual maturation in the boy usually begins with testicular enlargement between 9.5 and 13.5 years of age. The average duration of puberty for boys is 3 years with a range of 2 to 5 years.7,8 Clinical correlates of male and female pubertal maturation are described in Table 63-1.10

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree