Darier disease is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the ATP2A2 gene6 that typically presents in children aged 5 to 15 years as keratotic papules in “seborrheic” distribution involving trunk, scalp, face, and lateral aspects of the neck. Histopathologically, there is suprabasal acantholysis covered by dyskeratotic cells (corps ronds) and large parakeratotic cells (corps grains), in addition to papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis (Fig. 12.2). The main differential diagnosis includes Hailey-Hailey disease (benign familial pemphigus), which is also an autosomal dominant genodermatosis that presents after puberty as recurrent vesicles and erosions on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, there is suprabasal acantholysis and epidermal hyperplasia. However, in contrast to Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease shows full-thickness acantholysis (dilapidated brick wall pattern), and dyskeratosis is not prominent (Fig. 12.3).

Porokeratosis is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder that manifests in childhood and infancy as asymptomatic keratotic papules that enlarge progressively to form plaques with peripheral keratotic ridges. Four variants of porokeratosis can be seen in the pediatric population and include the classic plaque type of Mibelli, linear porokeratosis, porokeratosis palmaris, plantaris et disseminata, and punctate porokeratosis that is limited to palms and soles.7 Histopathologic features common to all types of porokeratosis include a cornoid lamella, a column of porokeratosis that corresponds to the peripheral keratotic ridges seen clinically. The cornoid lamella overlies an area of epidermal invagination and is associated with a diminished granular zone and vacuolated and dyskeratotic keratinocytes at the base that correspond to an abnormal clone of keratinocytes (eFig. 12.1).

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant dermatosis that is seen mostly in females because it is almost always fatal in males. Mutations in the NEMO/IKKγ gene located at Xq28 have been found to cause expression of the disease.8 The characteristic cutaneous manifestations evolve from crops of vesicles and bullae that heal with hyperkeratotic verrucous lesions followed by streaks and whorls of hyperpigmentation. Histologically, the vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis, intraepidermal vesicle formation, and eosinophil-rich dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate (Fig. 12.4). The verrucous stage is characterized by hyperkeratosis and varying degrees of papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes. Eosinophils are seen within the epidermis and the dermis (eFig. 12.2). The hyperpigmented stage corresponds to numerous melanophages in the dermis as in any other postinflammatory pigmentary change. The differential diagnoses of the vesicular stage include other bullous disorders such as bullous pemphigoid, whereas the late verrucous stage may resemble an epidermal nevus. The skin manifestations are self-limiting; however, the extent of systemic involvement dictates the clinical course.9

Spongiotic (Eczematous) Dermatitis

“Eczema” is the term often used to describe erythematous, scaling vesicular lesions with serum crust. This group of disorders includes atopic, contact, nummular, and dyshidrotic dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis is an inherited, chronic, pruritic skin disease and is the most common skin disease seen in children. About one-third of the cases are diagnosed before the age of 1 year and the vast majority of patients before 5 years. The lesions present as eczematous rash with dry, scaly, pruritic patches and plaques. Older lesions show lichenification and dyspigmentation. Sites of predilection are the face in young infants; extensor surfaces of extremities in children younger than 1 year of age; and the popliteal and antecubital fossae, face with sparing of nose, and neck in older children and adolescents. The major abnormality in this disease appears to be the overproduction of allergen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE). Cytokines, T cells, and antigen-presenting cells in addition to abnormalities of skin barrier appear to play a role in the pathogenesis. Mutations in filaggrin gene are found in many patients with atopic dermatitis.10

Contact dermatitis includes primary irritant dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. Primary irritant dermatitis is frequently seen in children on the cheeks caused by saliva, extremities in response to harsh soaps or detergents, and the diaper area from toiletries. Allergic contact dermatitis presents with pruritic, edematous papules, plaques, and occasionally vesicles 12 to 24 hours after exposure to an allergen such as poison ivy, fragrances, nickel, and rubber compounds. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs more frequently in children with atopic tendencies. Histopathologic features of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis vary with duration. In the acute phase, there is marked epidermal spongiosis with vesiculation (Fig. 12.5). In the subacute phase, the spongiosis is milder, but associated parakeratosis with plasma, neutrophils, and epidermal hyperplasia may be present. In the chronic phase, the spongiosis is mild to absent, but changes of chronicity are reflected in a hyperkeratotic cornified layer, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and fibrotic papillary dermis. Superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is present to varying degrees in all the phases. Numerous eosinophils may be seen in contact dermatitis.

Pityriasis rosea is an acute, self-limiting papulosquamous eruption most commonly seen in otherwise healthy adolescents and young adults. A possible viral etiology (human herpesvirus 7 and possibly 6) has been suggested.11 It typically presents with a single, large, scaly plaque, the herald patch on the trunk that is followed within a week by more disseminated smaller oval, scaly, pink papules along the lines of skin cleavage. Histologic sections show focal parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, and a mild superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Extravasated red blood cells are often present in the papillary dermis and may extend into the epidermis (eFig. 12.3). Biopsy of the herald patch also shows epidermal hyperplasia and denser infiltrate of inflammatory cells.

A chronic dermatosis of unknown cause, seborrheic dermatitis is quite common in infants aged 2 to 10 weeks and in adolescents. In infants, seborrheic dermatitis begins as an erythematous, scaly rash typically involving the scalp, face, and diaper area. In adolescents, it appears as a dry, fine exfoliation of the scalp (dandruff) and expands to the face with the clinical features sometimes overlapping with those of psoriasis. Histopathologic features overlap with psoriasis and spongiotic dermatitis and consist of epidermal hyperplasia and spongiosis with exocytosis and patchy parakeratosis, which is often present at the openings of the follicular infundibula (eFig. 12.4). A mild superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation is present in the dermis. Infantile seborrheic dermatitis may clinically mimic Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a potentially serious disorder, warranting a biopsy confirmation in recalcitrant cases.

Psoriasiform Dermatitis

Psoriasiform dermatitis is typified by Psoriasis vulgaris that presents in the first or second decades of life in a third of the patients. Psoriasis can present in various forms such as plaque type, guttate, pustular, and erythrodermic psoriasis. Of these, plaque type is the most common one seen in children followed by guttate psoriasis. Cutaneous lesions are characterized by asymptomatic, scaly, erythematous plaques in the plaque type and by slightly pruritic, small, red, droplike, scaly lesions in guttate psoriasis. Silvery scales that, on scraping, leave pinpoint areas of bleeding (Auspitz sign) are typical of psoriasis. Lesions are distributed in a bilaterally symmetrical pattern with predilection for scalp and extensor aspects of extremities. Involvement of face is more common in children than in adults and needs to be distinguished from atopic dermatitis. Similarly, psoriasis may involve the diaper area where it must be differentiated from infantile seborrheic dermatitis and other causes of diaper dermatitis. Classic histologic features of psoriasis include confluent parakeratosis with neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), regular elongation of epidermal rete with thin suprapapillary plates, dilated vessels in dermal papillae, and mild superficial perivascular inflammation (Fig. 12.6). The histologic differential diagnosis includes pityriasis rubra pilaris, which is also characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and parakeratosis. However, in pityriasis rubra pilaris, the suprapapillary plates are thick, the granular layer is prominent, and neutrophils are absent in the parakeratotic cornified layer (eFig. 12.5). Chronic spongiotic dermatitis such as contact or atopic dermatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of psoriasiform dermatitis; presence of spongiosis and eosinophils and absence of confluent parakeratosis with neutrophils in spongiotic dermatitis may be helpful in differentiation. Parakeratosis with neutrophils and spongiform pustules may be seen in dermatophyte infection and bacterial impetigo requiring periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Gram stains to exclude those possibilities.

Interface Dermatitis

Erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson (S-J) syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (Lyell syndrome) form the clinical and histopathologic spectrum of a potentially life-threatening group of disorders characterized by epidermal necrosis with formation of bullae, which can involve a large part of the skin surface and mucosa. S-J syndrome is more common in childhood than EM or TEN. EM is distinguished clinically by the characteristic iris or targetoid lesions that can occur on any part of the body but most commonly on the palms and soles. Erythematous and purpuric macules that progress to flaccid bullae and detach from the underlying dermis are characteristic of S-J syndrome and TEN. The detachment is extensive in TEN, whereas mucosal involvement is more prominent in S-J syndrome. The majority of cases of EM in children are etiologically related to herpes simplex virus infection; other viral infections including Epstein-Barr virus and mycoplasma infections have also been implicated.12 Drugs such as sulfonamides and penicillins play an important role, especially in the more severe S-J syndrome and TEN.13 No cause can be identified in a significant number of cases.

Histopathologic features include interface dermatitis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer and mild perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, which are also present along the dermoepidermal junction. An unaltered stratum corneum in skin biopsies attests to the acute nature of the assault on the skin. The histologic hallmark of this group of diseases is the necrotic keratinocyte, which may be few in milder forms and numerous with confluent areas of necrosis in more established lesions (Fig. 12.7). In TEN, full-thickness epidermal necrosis leads to subepidermal separation and loss of epidermal surface with the eroded clinical appearance of skin originally described by Lyell (Fig. 12.8). Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome can be clinically similar to TEN; however, microscopically, it shows a split in the granular layer rather than at the dermoepidermal junction and no epidermal necrosis. Acute graft-versus-host disease is characterized by interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes similar to EM. The presence of lymphocytes around the necrotic keratinocytes (satellite necrosis) is characteristic (eFig. 12.6).

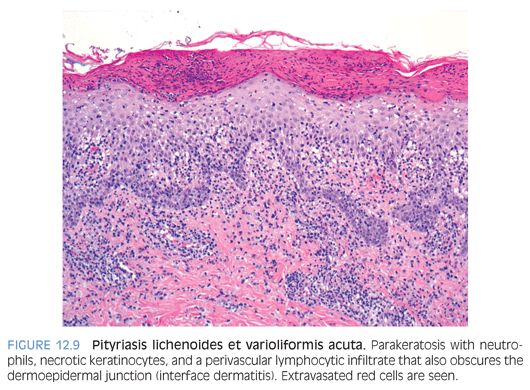

Pityriasis lichenoides is a self-limiting cutaneous eruption of unknown cause that occurs in children, teens, and young adults. An acute, more severe form, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA; Mucha-Habermann disease), and a chronic milder form, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, are recognized. PLEVA is characterized by an extensive papular, papulonecrotic, and occasionally, vesiculopustular eruption on the trunk and proximal extremities that resolves within a few weeks. As the older lesions resolve, crops of newer lesions continue to appear, and the overall course may be protracted to several months. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is characterized by recurrent crops of reddish-brown papules with an adherent scale that typically resolve within 3 to 6 weeks without scarring. Histopathologic findings in the acute form include interface dermatitis with a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Confluent parakeratosis with serum crust–containing neutrophils, epidermal spongiosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and extravasated red cells are present (Fig. 12.9). In the chronic form, the histologic changes are similar, but parakeratosis with neutrophils is not conspicuous. Melanophages may be seen in the superficial dermis (eFig. 12.7).

Clinical and histopathologic findings of pityriasis lichenoides may overlap with lymphomatoid papulosis that is distinguished by the presence of CD30-positive atypical lymphoid cells.

Interface Dermatitis, Lichenoid Type

Lupus erythematosus occurs in all forms in children, with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) being the most common. Childhood SLE peaks in early adolescence, with about 60% of cases occurring between the ages of 11 and 15 years. Cutaneous manifestations are the second most frequent finding (77%) after renal involvement (84%). Discoid lupus erythematosus without clinical serologic evidence of systemic disease can occur rarely in children. Neonatal lupus erythematosus is seen in newborn infants born to anti-Ro (SS-A) antibody–positive mothers with the development of skin lesions and/or heart block at birth to 2 months of age.14 The skin lesions consist of erythematous, nonscaling, sharply demarcated lesions with a predilection for involvement around the eyes and occasionally, annular polycyclic type of lesions commonly seen in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Biopsies of early lesions of SLE corresponding to the erythematous malar rash show only nonspecific changes. The histology of well-established SLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, neonatal lupus erythematosus, and discoid lupus erythematosus is essentially similar, varying only in degree. The characteristic changes are those of interface dermatitis with marked vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer and a lymphocytic infiltrate that obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Additional findings include hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy and follicular plugging, most prominent in discoid lesions, and perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate. A thickened basement membrane is seen in older lesions (Fig. 12.10). Direct immunofluorescence reveals a continuous granular deposit of C3, immunoglobulin G (IgG) and, occasionally, immunoglobulin M (IgM) along the dermoepidermal junction in involved and uninvolved skin in SLE and only in involved skin in discoid lupus erythematosus (eFig. 12.8).

Lichen planus is generally a self-limiting pruritic eruption that can occur in children.15 The clinical appearance of the eruption is distinctive and consists of flat-topped violaceous papules involving flexor aspects of the extremities and lower back. Lichen planus can also involve hair, nails, and mucous membranes in a significant number of cases. The histologic features are distinctive and consist of hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and a band-like lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obscures the dermoepidermal junction (Fig. 12.11). Melanophages are seen in the infiltrate in older lesions.

Lichen nitidus is an asymptomatic dermatosis of childhood, characterized by usually asymptomatic, round, flat-topped papules that measure only a few millimeters. Histologically, the inflammatory cell infiltrate is band-like but small and discrete. The infiltrate confined to widened dermal papillae and enclosed by elongated rete results in the characteristic appearance of a claw clutching a ball. Presence of numerous histiocytes in the infiltrate and focal parakeratosis are helpful in differentiating lichen nitidus from lichen planus (eFig. 12.9).

Lichen striatus is a common papulosquamous dermatosis most commonly seen in children. It presents as numerous small (1 to 3 mm) skin-colored to hyperpigmented papules arranged in a linear distribution along Blaschko lines on extremities, trunk, or neck. The eruption is usually unilateral. Histologic features include a lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate similar to lichen planus. Distinguishing features include the presence of inflammatory cell infiltrate deep in the reticular dermis around hair follicles and sweat glands. Parakeratosis, epidermal spongiosis, and an admixture of histiocytes in the inflammatory cell infiltrate can be present.

Vesiculobullous Disorders

Linear immunoglobulin A (IgA) bullous dermatosis is an immune-mediated vesiculobullous eruption that presents in both adults and in children. The childhood form, also known as chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood, occurs in prepubertal children, often younger than 5 years of age, as widespread vesicles and bullae, sometimes arranged like a string of pearls at the periphery of a healing lesion. Sites of predilection include the lower part of the trunk, including the groin and genitalia, and perioral areas. Microscopic features are essentially indistinguishable from dermatitis herpetiformis and consist of neutrophilic microabscesses at the tips of dermal papillae in early lesions and subepidermal bulla filled with neutrophils or eosinophils in well-established lesions (Fig. 12.12). Direct immunofluorescence studies show a distinct linear pattern of staining at the basement membrane zone with IgA (eFig. 12.10) in sharp contrast to the granular IgA deposits seen in dermatitis herpetiformis. Direct immunofluorescence testing is also crucial in differentiating chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood from other bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (linear deposition of IgM/IgG and C3) and bullous lupus erythematosus (granular deposits of IgM/IgG and C3).

Dermatitis herpetiformis presents as an intensely pruritic papulovesicular eruption that is distributed symmetrically on the extensor aspects of extremities, buttocks, and back. The lesions may be grouped in herpetiform fashion. Approximately 75% to 90% of the children with dermatitis herpetiformis have an associated gluten-sensitive enteropathy and a high frequency of human leukocyte antigen (HLA), including HLA-B8 and HLA-DR3. Histologic sections of a papular lesion show the characteristic neutrophilic microabscesses at the tips of the dermal papillae. Biopsy of a clinically apparent vesicle shows a subepidermal bulla filled with neutrophils and a varying mixture of eosinophils and fibrin. Microabscesses are present in the papillary dermis at the edge of the blister (Fig. 12.13). Direct immunofluorescence testing is positive for granular deposits of IgA at the tips of dermal papillae in almost all patients (eFig. 12.11). A gluten-free diet is effective in controlling the intestinal and cutaneous manifestations in most children.16

Neutrophilic Dermatosis

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome) is typically seen in adults and occasionally in children and is characterized by fever; leukocytosis; and violaceous plaquelike lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. Underlying myeloproliferative disorders, particularly acute myelogenous leukemia, may be seen in up to 20% of cases. A skin biopsy shows papillary dermal edema and a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without true vasculitis (Fig. 12.14).17,18 Histologic differential diagnoses include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and infectious etiologies.