Sexually Transmitted Infections

Loris Y. Hwang, Anna-Barbara Moscicki, and Mary-Ann Shafer

Currently, substantial numbers of adolescents engage in sexual intercourse: 34% have experienced their sexual debut by ninth grade and 63% by 12th grade.1 Although these rates have slowly decreased from 15 years ago the adolescent age group continues to be at the highest risk for STIs.

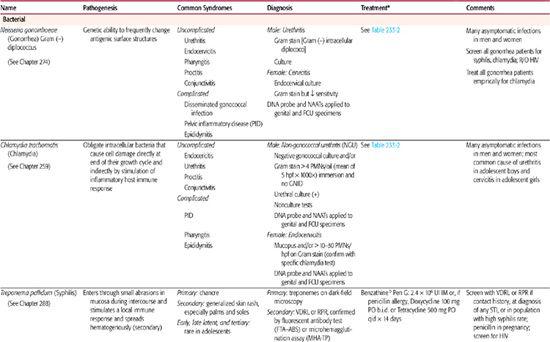

This chapter provides an overview of common STIs including the pathogenesis, common clinical syndromes, diagnostic approach and treatment for bacterial, fungal and viral infections (see Table 233-1), and for clinical For the most contemporary guidelines on treatment regimens it is useful to refer to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) web site since alterations in optimal treatment approaches may change as antibiotic-resistance patterns and the availability of specific medications changes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Adolescents 15 to 24 years of age represent one quarter of the sexually active population, but they acquire nearly half (9.1 million) of the new STIs each year in the United States.2,3 These STIs place our youth at risk for pelvic inflammatory disease and associated sequelae of ectopic pregnancy and infertility, genital cancers, and even death through complications of STIs, especially HIV infection.

Commonly reported prevalences of STIs among sexually active adolescent girls both with and without lower genital tract symptoms include Chlamydia trachomatis (10–25%), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (3–18%), syphilis (0–3%), Trichomonas vaginalis (8–16%), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) (2–19%).4 Among adolescent boys with no symptoms of urethritis, isolation rates include C trachomatis (9–11%) and N gonorrhoeae (2–3%). Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA has been detected in 20% to 60% of female adolescents.

Gender is an important factor in the epidemiology of STIs, because both the rates of infection and sequelae are disproportionately higher among females compared to males. In 2006, among 15- to 19-year-olds, the female-to-male ratio of rates for chlamydia was 6.4, and for gonorrhea was 2.3.2 During the same year, the ratios of C trachomatis for African American, Native American, Hispanic, and white youth were 8:4:2:1, and those for N gonorrhoeae were 18:3:2:1. The ratios for primary and secondary syphilis among these same groups were 29:< 1:2:1. Trends in rates of N gonorrhoeae among youth show an increase for the second consecutive year. From 2005 to 2006, the rate for 15- to 19-year-olds increased by 6.3%. It is important to note that the relationships between the ethnicity and STIs including AIDS have been confounded by socioeconomic factors. In addition to age, gender, and ethnicity, a number of important biological and behavioral factors may help to explain these epidemic rates of STIs among adolescents.

Although adolescents currently represent fewer than 1% of the estimated number of people living with infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the United States, the number of estimated cases among ages 20 to 24 is 7-fold greater than that among ages 15 to 19.2 Because of the long latency period of the disease (2 to 7 years or more), it is probable that many young adults with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were infected with HIV during adolescence. The HIV seropositivity data available from screening programs show a rate of < 1/1000 for military recruits, 3.6/1000 for Job Corps applicants, and 50/1000 for runaway youth. Among new cases of HIV/AIDS in 2000–2004, male-to-male sexual contact was cited as the most common transmission route, but the greatest increasing trend in new cases was observed among cases of heterosexual transmission, including among adolescents.

CONTRACEPTIVES AND SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES

Condoms have been shown consistently to prevent STIs, especially gonococcal and chlamydial infections, and assist in preventing HIV infection, as well. However, only one half of 15- to 19-year-old females reported using condoms during last intercourse.5 Inadequate contraceptive use by adolescents is reflected in high pregnancy and STI rates.

Oral contraceptives have been linked to some sexually transmitted infections (STIs). For example, candidal infections have long been associated with oral contraceptive use. Controversy surrounds the role of oral contraceptives and the establishment of endocervical infection and development of PID with N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis. It appears that oral contraceptive users have fewer gonococcal endocervical infections, and when gonococcal PID occurs, it is less severe. The impact of oral contraceptives on the establishment of chlamydial endocervical infections is less clear, but most studies show an increased risk for chlamydial infection among oral contraceptive users. Oral contraceptive users, however, appear to have less chlamydial PID.

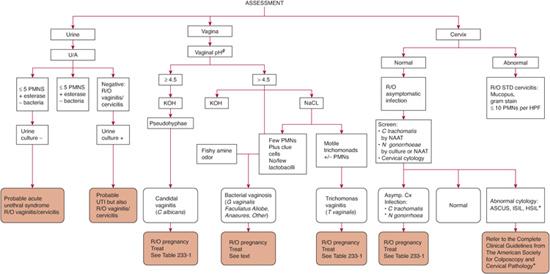

Table 233–1. Common Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Adolescents

Of note, spermicides containing nonoxynol-9 (N-9) are no longer recommended for STI prevention, as they have not been effective in the prevention of several STIs.6 Furthermore, disturbance of epithelial surfaces has been associated with frequent use of N-9 products and places youth at even higher risk for HIV acquisition. Thus, N-9 products are actively discouraged.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE

N gonorrhoeae is the second most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States. N gonorrhoeae is a gram-negative bacterium that has the unique genetic ability to change the antigenic expression of its surface-exposed proteins, making development of a vaccine challenging. For further details of pathogenesis and diseases due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae see Chapter 274.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

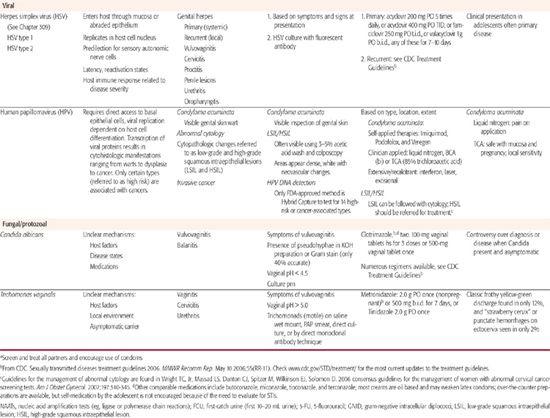

The most common manifestation of gonococcal disease among men is urethritis, which may be asymptomatic.6 After urethral inoculation with the organism during sexual activity, it is estimated that 2 to 4 days elapse before symptoms of dysuria or discharge appear. The discharge may be scant, and mucoid may be present as a profuse purulent discharge. Untreated gonococcal urethritis in men typically resolves over 1 to 2 months but may progress in up to 10% of cases to acute epididymitis and urethral strictures. An outline of the evaluation of urethritis is presented in Figure 233-1. Although women have urethral infections, they are usually associated with endocervical infection. Most gonococcal infections in women affect the lower genital tract with a particular predilection for the columnar cells of the endocervix. Syndromes in both men and women are outlined in Table 233-1. In particular, disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), a blood-borne infection manifested by skin lesions, tenosynovitis, and septic arthritis (culture-positive joint fluid in approximately 50% of cases only), occurs in 2% to 5% of infected individuals. It is more common in African Americans than in other race/ethnicity groups. Pelvic inflammatory disease is another important complication of gonococcal infection and is discussed later in this chapter, and in Chapter 274.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

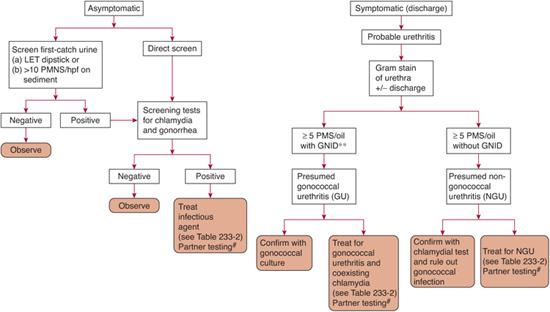

Diagnostic tests are outlined in Table 233-1, evaluation of both urethritis and vaginitis is found in Figure 233-1 and Figure 233-2, and treatment regimens are summarized in Table 233-2.6 Several tests are available for the specific diagnosis of gonoccocal infection: the traditional culture, nucleic acid hybridization tests, and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs).7 NAATs are rather versatile in that they are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for samples obtained from the female endocervix, vagina, and urine, and the male urethra and urine. Samples taken from the female endocervix or male urethra are necessary for culture or nucleic acid hybridization tests. In men who have symptoms of urethritis, another diagnostic tool is the Gram stain of the urethral specimen. Evidence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with intracellular gram-negative diplococci is considered diagnostic. For samples from asymptomatic men or other anatomic sites, Gram stain is considered insufficient and is not recommended. For samples taken from the rectum or pharynx, culture is the usual test of choice.

FIGURE 233-1. Assessment of urethritis in sexually active male adolescents. *First 15 mL of micturition of urine sample tested. (Left) Unspun urinary leukocyte esterase test (LET) for positive activity, or (right) spun-resuspended shows ≥10 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-power field. **GNID, gram-negative intracellular diplococci; #, All partners from the previous 60 days (or the most recent partner if there was no history of sexual activity in the last 60 days) should be tested, treated, and counseled on safer sex practices. hpf, high power field; oil, oil immersion field; PMNS, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

FIGURE 233-2. Assessment of lower genital tract infection in sexually active female adolescents. Complete assessment should be performed whether or not symptoms are present. #Vaginal discharge, pruritus, dysuria/frequency; *R/O pregnancy before treatment. PMNS, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test. +Guidelines for the management of abnormal cytology are found in Wright TC, Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:340-345. ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; HSIL, high-grade intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade intraepithelial lesion; R/O, rule out; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Table 233–2. Treatment of Uncomplicated Genital, Anal, and Pharyngeal Chlamydial and Gonococcal Infections

For uncomplicated chlamydial infection: |

azithromycin 1 g orally × 1 dosea |

or |

doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily × 7 days |

For uncomplicated gonococcal infection: |

cefixime 400 mg orally × 1 dosea |

or |

ceftriaxone 125 mg IM × 1 doseb |

plus |

(always treat for possible chlamydial coinfection) |

azithromycin 1 g orally × 1 dosea |

or |

|

For chlamydial infection in pregnancy: |

azithromycin 1g orally × 1 dose |

or |

amoxicillin 500 mg PO t.i.d. × 7 days |

For sexual partners: |

Contact, evaluate, and treat partners in the past 60 days or most recent partner if > 60 days for asymptomatic for both chlamydial and gonococcal disease. Condoms should be used. Abstain from sexual activity at least 7 days after treatment. |

For follow-up: |

Retest at 3 to 4 months to R/O recurrent infection. Counsel about safer sex practices. |

aIt is possible to treat both uncomplicated chlamydial and gonococcal infections with 1-dose oral regimens. Cost factors must be evaluated locally. The effect of such regimens on incubating syphilis is not known.

b90% effective against gonococcal pharyngitis. Quinolones are no longer recommended in the treatment of gonococcal infection due to resistance

From CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. May 10 2006;55 (RR-11). (Check www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/ for the most current updates to the treatment guidelines.)

Treatment is determined by the following considerations: (1) the anatomic site of infection; (2) the antibiotic resistance [penicillinase-producing strains (PPNG), tetracycline-resistant strains (TRNG), quinolone-resistant strains, and chromosomally mediated resistance to multiple antibiotics]; (3) high prevalence of concurrent chlamydial infections in patients with gonococcal infection; and (4) the side effects and costs of different treatment regimens. In recent years, quinolone resistance has continued to spread substantially. It is imperative that clinicians check the up-to-date CDC Web site (www.cdc.gov/std/treatment) for the most current treatment guidelines at the time of the patient’s treatment. Unless a chlamydial NAAT is known to be negative at the time of gonococcal treatment, patients should also receive empiric chlamydial treatment concurrent to their gonococcal treatment. Treatment regimens that include ceftriaxone or a 7-day course of doxycycline (or erythromycin) may be effective against incubating syphilis, but few studies are available. Therefore, all patients with an STI should be screened for syphilis serologically as well as HIV. All partners from the previous 60 days (or the most recent partner if there was no history of sexual activity in the last 60 days) should also be tested, treated, and counseled on safer sex practices.

Treatment for disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) requires initial parenteral therapy and evaluation for possible meningitis or endocarditis. The recommended regimen for initial treatment is ceftriaxone, 1 g IM or IV q24h; an alternative regimen (allergy to β-lactams) is spectinomycin, 2 g IM q12h. Compliant patients may be discharged 24 to 48 hours after symptom resolution but need to complete at least another 7-day course of oral medications, for example, cefixime, 400 mg PO BID.

CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS

C trachomatis is the most common reported bacterial STI in the United States. The pathogenesis of C trachomatis infections has not been clearly defined. Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria, and disease appears to result from both the destruction of cells during the growth cycle and the body’s immune response to the infection producing inflammation. An overview of syndromes, diagnosis, and treatment of C trachomatis is found in Tables 233-1 and 233-2.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

Among women, 50% or more of chlamydial lower genital infections are asymptomatic. Uncomplicated endocervicitis is the most common clinical manifestation of chlamydial infection in sexually active female adolescents. Clinical findings may include mucopurulent cervicitis (MPC), which presents with a yellow endocervical discharge on a swab sample or by identification of increased polymorphonuclear cells on a Gram stain from the discharge (more than 10 to 30 per high-power field). C trachomatis has been identified in 9% to 51% of MPC cases, with N gonorrhoeae being responsible for some cases as well. However, MPC is not a sensitive diagnostic indicator of infection, because most infected women do not have MPC. Chlamydial cervicitis may also be accompanied by abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding, especially after intercourse. Diagnosis by direct testing for C trachomatis is encouraged (Table 233-1). The most serious complication of endocervical infection is pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), including a subclinical form of PID that also may lead to infertility. Asymptomatic and symptomatic urethritis can be caused by chlamydial infection in both men and women. In men, 20% to 50% of those with gonococcal urethritis are also infected with C trachomatis. C trachomatis is the most common cause of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) in men, responsible for 23% to 55% of cases. Men with NGU may present with discharge and dysuria. The infection is identified through contact tracing from a C trachomatis-positive partner, routine screening of those at risk, or testing of symptomatic men.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

There are a number of situations such as NGU, PID, epididymitis, and confirmed gonococcal infection which are associated frequently with chlamydia infections and necessitate immediate “presumptive” treatment to alleviate symptoms and to prevent complications and further transmission to partners. For example, 5% to 30% of men and 25% to 50% of women with N gonorrhoeae infection have concurrent C trachomatis infection. However, regardless of whether presumptive treatment is administered to the patient and partner, chlamydia testing in both the patient and partner should still be undertaken when possible, together with screening for other STIs and thorough counseling regarding safer sex practices.8 Testing for C trachomatis is performed by using either the traditional “gold standard”—the cell culture—or the newer nonculture techniques—NAATs and other nucleic-acid-based testing.7 Although cell culture is being largely surpassed by more sensitive nonculture techniques, the use of cell culture as the test of choice is still warranted for urethral and rectal specimens in men and women, vaginal specimens in prepubertal girls, and sexual assault or abuse cases involving legal issues. In these situations, nonculture methods have not been FDA approved, have been inadequately studied, or have yielded inadequate performance profiles.

The FDA-approved NAATs include the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that amplifies chlamydial DNA found in urine and cervical specimens. Other currently available tests for chlamydia include the direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test, the enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test, the DNA probe test, the rapid chlamydia test, and the leukocyte esterase dipstick test (LET). Of interest to the primary-care clinician is the rapid ability to utilize the nonspecific LET in cases of possible urethritis in male patients. The LET is applied to the first-void urine specimen (first 10–15 mL voided into pre-marked container) for evaluation of urethritis, which is most frequently caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. Because the sensitivity of the LET in screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea is 46% to 100% (it is a nonspecific indicator of the presence of polymorphonuclear cells), it is necessary to follow all positive LETs with more specific tests for C trachomatis and N gonnorhoeae (eg, NAATs, culture). Data are insufficient to support the use of the LET to screen young women for C trachomatis. The treatment protocols are outlined in Table 233-2. All patients should be retested for recurrence of C trachomatis at 3 to 4 months after treatment.

PROTOZOAN AND FUNGAL INFECTIONS

TRICHOMONAS VAGINALIS

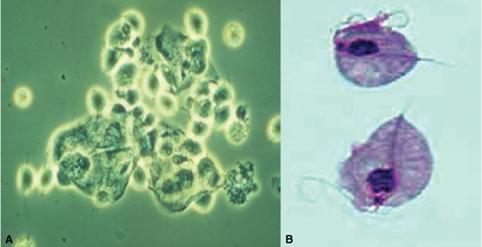

Trichomonads are flagellated protozoans. Three species are linked to disease in humans: Trichomonas vaginalis (genital organs of men and women), Trichomonas tenax (mouth), and Pentatrichomonas hominis (intestine). T vaginalis is known to attach to epithelial cells and has been shown to be sexually transmitted. The organism has also been shown to survive for up to 1.5 hours on a wet sponge and 24 hours on a wet cloth.

The pathogenesis of disease in humans is not completely understood. The response to infection varies from little or no reaction (carrier state) to an acute inflammatory response marked by the presence of numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Half of all asymptomatic carriers of T vaginalis become symptomatic within 6 months. Development of disease in women appears to be related to the menstrual period, pubertal development, vaginal pH, and environmental microbiological flora. Prevalence in adolescent women has been reported to be 2% to 30%, depending on the population examined.10,11

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

Syndromes associated with the Trichomonas infection include vaginitis and cervicitis in women and urethritis in both men and women.12 In infected women, 25% to 50% are asymptomatic. Genitourinary symptoms include vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, pruritus, lower abdominal pain, dysuria, and frequency. On examination, the vulva is often erythematous, and copious vaginal discharge may be present. On speculum examination, the vaginal walls appear granular in over half the cases. Although a discharge is common, the “classical” frothy yellow-green discharge occurs in only 12% and has been described in other causes of vaginitis. The “strawberry cervix” (punctate hemorrhages on the exocervix), which in the past was erroneously considered pathognomonic for T vaginalis cervicitis, occurs in only 2% of the infections. In men, the infection is usually self-limited, and most men are asymptomatic or present with features of nongonococcal urethritis (Table 233-1). Infrequently, epididymitis or proctitis may develop.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree