Scrotal Masses

David J. Breland and Mark L. Rubinstein

TESTICULAR TORSION

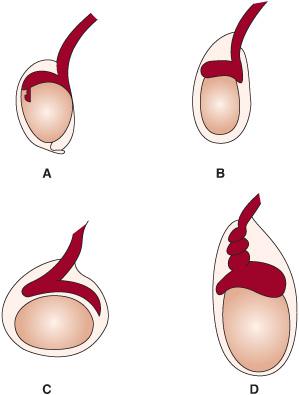

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency, and clinicians caring for adolescent males must have a high index of suspicion given the short window for salvage of the testicle. Common presentation includes abrupt onset of severe scrotal pain with associated nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain.1-3 Symptomatic males may describe prior transient episodes of scrotal pain consistent with intermittent torsion/detorsion.1 The exact etiology of torsion is unknown. However, a well-described anatomical abnormality called the “bell clapper” deformity can predispose to testicular torsion (see Figure 75-1). In this deformity, the tunica vaginalis completely surrounds the testicle, including the posterior aspect, and the absence of the normal posterior anchoring allows the testicle to twist freely. On physical examination, if the adolescent presents early, the testicle may have a horizontal lie with minimal swelling.1-3 Typically, the adolescent presents later, and the scrotum is swollen, tender, erythematous, and often difficult to examine.1-4 The cremasteric reflex is nearly always absent.1-3 Diagnosis can be made on physical examination or with the assistance of color Doppler ultrasound, which has a sensitivity of 89% to 100% and a specificity of 77% to 100%.2,4 Time is of the essence because testicular viability declines to zero after 24 hours.2-4 Treatment involves prompt surgical exploration and detorsion. Given the high incidence of retorsion, as well as torsion of the contralateral testis, once detorsed, the affected testis and the contralateral testis are fixed to the scrotum in a procedure called scrotal orchiopexy.2,3

TORSION OF TESTICULAR OR EPIDIDYMAL APPENDAGE

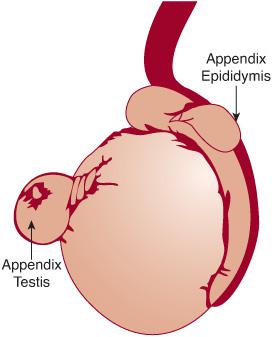

Both the testis and the epididymitis have appendages (see Figure 75-2) that are remnants of the wolffian and müllerian ducts, respectively.3 The typical presentation of appendiceal torsion occurs in boys ages 7 to 12 years and includes pain that may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting.2 Palpation of the testis reveals tenderness over the superior or inferior pole of the testes with or without a palpable mass.5 The cremasteric reflex is usually present. The classic “blue dot” sign, if present, represents the infarcted appendage viewed through the scrotal skin.1,3,5 The diagnosis is usually made on clinical examination. If torsion of the testis cannot be ruled out, a color flow Doppler examination is indicated.5 Treatment is usually supportive, including analgesics, anti-inflammatory agents, and scrotal elevation.1 If pain persists for longer than 5 days, consultation by a pediatric urologist is recommended.3

FIGURE 75-1. A: The normal testicle. B: Bell clapper deformity in which the tunica vaginalis completely surrounds the testicle, including the posterior aspect, such that the normal posterior anchoring is absent. C: Early presentation of torsion with swelling and horizontal lie of the testicle. D: Torsion of the testicle.

TRAUMA

Trauma may be a cause of pain and swelling of the scrotum. When the presentation includes an overlying hematocele, surgical exploration and repair may be required for testicular salvage.5

FIGURE 75-2. Testicular appendages.

HERNIA AND HYDROCELE

Both hernias and hydroceles are related to congenital abnormalities in the inguinal canal. Inguinal hernias are further discussed in Chapter 405. Communicating hydroceles develop when fluid tracks down the inguinal canal into the tunica vaginalis. Hydroceles may also form from trauma, infection (eg, epididymitis and orchitis), testicular torsion, or tumors. Indirect hernias form when a loop of bowel passes through the inguinal canal. Both can present as a scrotal mass. However, on examination, hernias are usually firmer than hydroceles and do not transilluminate. Additionally, bowel sounds may be auscultated over hernias. The hydrocele is usually painless and can shift in size when the patient is supine. In most patients, a hydrocele will transilluminate showing the presence of fluid. When palpated, it may feel like a supple, fluid-filled cyst. Hydroceles are corrected electively. Hernias can become incarcerated and therefore are usually repaired surgically.1

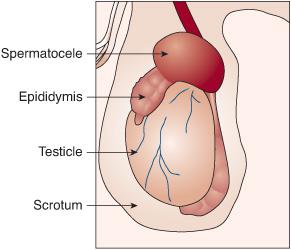

SPERMATOCELE

Spermatocele refers to the accumulation of sperm within the head of the epididymis6 (see Figure 75-3). Spermatoceles, which are benign cysts, are commonly found on routine physical examination or by the adolescent himself and usually do not require intervention unless symptomatic.3 On palpation, they are predominantly smooth, soft, well circumscribed, and found on the superior aspect of the testicle. In addition, these cystic lesions may transilluminate.2

ORCHITIS

Orchitis rarely occurs in prepubertal males.5 The mumps virus is the most common cause of orchitis, but other viruses have been implicated (eg, coxsackivirus, echovirus, adenovirus, varicella). Mumps orchitis usually follows parotitis by about 4 to 8 days, but presentation up to 6 weeks later has been reported. The typical presentation includes edema, erythema, and tenderness of the testicle and may be associated with constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, nausea, lower abdominal pain).7 Bacterial orchitis is usually a consequence of the contiguous spread from an epididymal infection.5,7 Viral orchitis is treated supportively with rest and analgesia. Bacterial orchitis is treated with antibiotics and supportive care. Infertility is a rare complication of orchitis.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree