2Nottingham Breast Institute, City Hospital, Nottingham, UK

3NHS Cancer Screening Programmes, Oxford University, Oxford, UK

Overview

- Screening for breast cancer reduces mortality but does not reduce incidence

- Screening of women (over the age of 50) has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality from breast cancer

- Currently mammographic screening is the only method of screening that has been shown to be effective on a population basis

- MRI screening in younger women (<50 years of age) who are gene carriers has been shown in randomised studies to be effective in identifying cancers at an early stage

- Screening is not without morbidity and efforts are continuing to reduce recall rates, false positive rates etc.

Lack of knowledge of the pathogenesis of breast cancer means that primary prevention is currently a distant prospect for most women. Early detection represents an alternative approach for reducing mortality from this disease.

Screening can be targeted at populations at risk (for example women aged ≥50) and high-risk groups (for example younger women with a significant genetic risk; see Chapter 5). There is no evidence that either clinical examination or teaching self-examination of the breast is an effective tool for early detection. The former has been the subject of clinical trials.

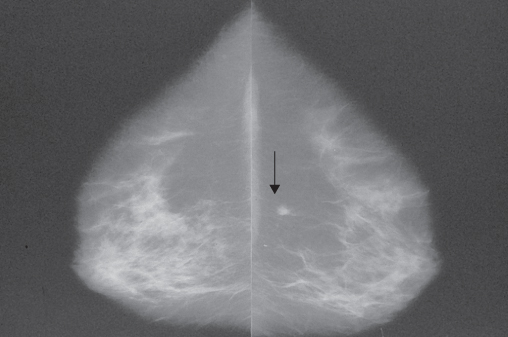

Screening tests should be simple to apply, cheap, easy to perform, straightforward and unambiguous to interpret, and identify those with disease and exclude those without. Mammography requires high-technology equipment, highly trained staff to perform the examinations and highly trained readers to interpret the images (Figure 7.1 and Table 7.1). Mammography is at present the best screening tool available for population screening and was the first screening method for any malignancy that has been shown to be of value in randomised trials. Digital mammography is now replacing conventional film/screen mammography as it offers significant logistic advantages and better screening performance, particularly in younger women and those with dense breasts. There is some evidence that ultrasonography of the mammographic dense breast can improve sensitivity. Magnetic resonance imaging seems to be valuable in screening younger high-risk groups. Digital mammography tomosynthesis (DBT) is currently being evaluated as a screening technique. Dedicated breast computed tomography (CT) is currently being developed as a potential technique to image the breast.

Table 7.1 Detection of breast cancer after an initial screening in women aged 50–70.

| No. of women | |

| Initial screen | 10 000 |

| Recall for assessment | 500–700 |

| Surgical biopsy | <100 |

| Breast cancer detected | 60–70 |

Population Screening

Effect on Mortality

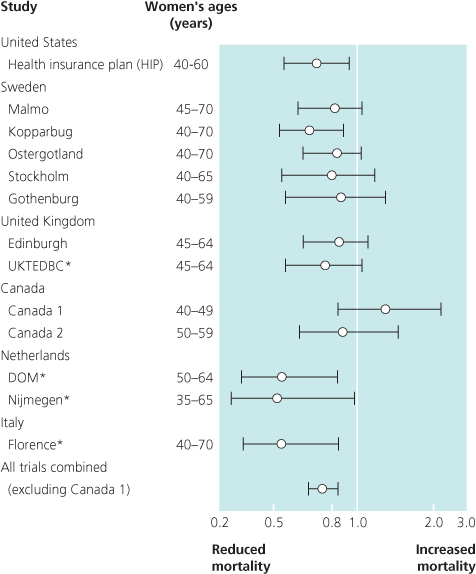

Randomised controlled trials have shown that screening by mammography can significantly reduce absolute mortality from breast cancer by up to 40% in those who attend (Figure 7.2). The benefit is greatest in women aged 50–70. Published data from the combined Swedish trials show an overall significant reduction in mortality from breast cancer of 21% during 15 years of follow-up in women aged 40–74, with the most benefit seen in women aged 55–69 (30%).

Figure 7.2 Summary of 7–12-year mortality data from randomised and case-control (*) studies of breast cancer screening. Points and lines represent absolute change in mortality and confidence interval.

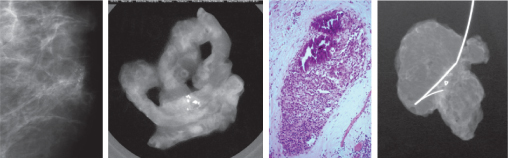

Figure 7.3 Screening mammogram (left) showing a small cluster of suspicious microcalcifications; (left middle) core biopsy specimen radiograph showing satisfactory sampling; (right middle) histology showing comedo DCIS; and (right) the excised specimen radiograph showing complete excision of this small focus of DCIS.

Acceptance, Quality Assurance and Monitoring

Over 70% of the target population must participate if screening is to reduce mortality significantly, and the cost per life year saved rises if fewer participate. To achieve optimal participation, accurate lists of names, ages and current addresses are required (Table 7.2). Factors affecting attendance for screening include the level of encouragement by general practitioners, knowledge about the disease and the screening programme, and the views and experiences of family and friends. Screening programmes must include both the initial screening process and the assessment of abnormalities detected by screening and have clearly defined treatment pathways when these are necessary.

Table 7.2 Requirements for organising population screening.

|

Standards must be set to ensure that targets for mortality reduction are likely to be achieved and that there is quality assurance at each stage of the screening process (Table 7.1). Multidisciplinary teams experienced in the management of breast disease should carry out screening and assessment.

Specific training and regular education programmes related to screening should be mandatory for all professionals involved, and regular audit and review of individual and programme results and performance are necessary.

Age Range

Current data indicate that absolute reduction in mortality is greatest in women aged 55–69 (30%). A smaller reduction in mortality of 20% could be achieved in younger women (40–54), but screening is less cost effective because of the lower incidence of breast cancer in these women and the high proportion of false-positive screening results. In Europe the consensus view is that mammographic screening of younger women on a population basis cannot be justified. In the United Kingdom screening is by invitation from age 50–70 inclusive. The age rage is being extended in England to 47–73 as a randomised study to assess the mortality benefit of starting screening from the age of 47 and continuing up to the age of 73.

Frequency of Screening

In the United Kingdom the interval between mammographic screens was selected from evidence from the Swedish two counties study and is every three years. A UKCCCR trial comparing annual with standard triennial mammographic screens has shown a small but insignificant advantage for annual screening of women. Screening needs to be shorter than the mean sojourn time for age. For women over 60 an interval of three years seems to be effective. For women aged 50–60, the ideal screening interval is probably between two and three years. If screening is offered to women aged <50, it should be annual.

Screening Method

There is clear evidence that two mammographic views of each breast (mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal) significantly improve both sensitivity, particularly for small breast cancers, and specificity.

A comparison of performance in UK screening units showed a 42% increase in the detection of carcinomas measuring 15 mm in units that use two views (Table 7.3). There is also emerging evidence that digital breast tomosynthesis increases the specificity of screening mammography. Trials are ongoing to assess the sensitivity effect of this technique. Double reading of films improves sensitivity by 5–12%. Single reading with computer-aided detection (CAD) has been shown to provide near equivalent sensitivity to double reading.

Table 7.3 Results from the NHSBSP 2007–08 in women aged >50.

| Total number of women invited | 2 576 136 |

| Acceptance rate (50–70 years) | 73.40% |

| Number of women screened (invitation) | 1 889 470 |

| Number of women screened (self/GP referral) | 105 181 |

| Total number of women screened | 1 994 651 |

| Number of women recalled for assessment | 83 222 |

| % women recalled for assessment | 4.2% |

| Number of benign biopsies | 1716 |

| Number of cancers detected | 16 449 |

| Number of in situ cancers detected | 3257 |

| Number of invasive cancers <15 mm | 6878 |

| Standardised detection ratio (invited women 50–70 years only) | 1.45 |

The Screening Process

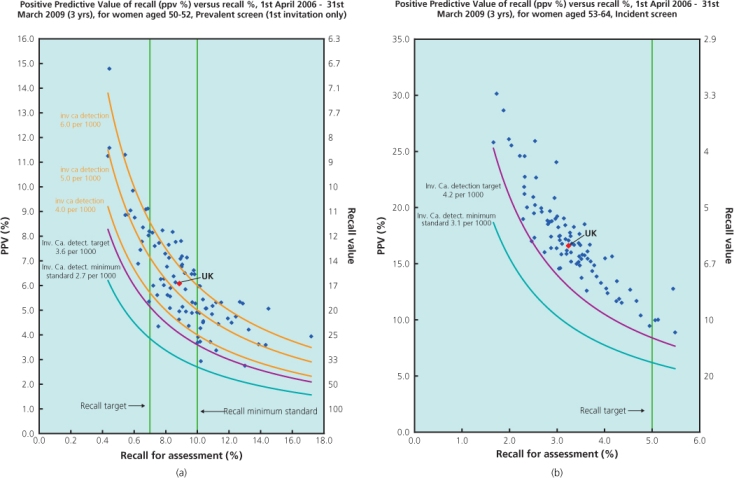

The first part of screening is the basic screen. All screening units need to attain and maintain appropriate levels of sensitivity and specificity. Among women aged 50–52, a minimum of 27 invasive cancers and 4–9 ductal in situ cancers (DCIS) should be detected for every 10 000 women who attend an initial (prevalent) screen. At subsequent screens (at ages 53–70) at least 30 screen-detected invasive cancers and 5–10 DCIS per 10 000 are expected (Table 7.4). More than 55% of all invasive cancers detected should be less than 15 mm in diameter (measured pathologically). The effectiveness of individual screening units is measured using the standardised detection ratio (SDR). Using data from the two counties study in Sweden, an SDR of 1.0 is predicted to provide a mortality reduction of 25% in the population. The minimum standard for SDR in the NHSBSP is 1.0 and the expected standard is 1.4, 40% higher cancer detection than originally achieved, reflecting the increase in underlying breast cancer incidence over the past 20 years. Recall rates for assessment should be less than 7% among prevalent attendees and less than 5% at subsequent screens. Women with a ‘normal’ screening outcome should be informed of their result by letter within two weeks. Patients judged to have an important abnormality require further assessment. The positive predictive value of recall plotted against the recall rates is used as a comparative measure of screening and assessment quality (Figure 7.4).

Table 7.4 Expected results from screening 10 000 women.

| No. of women | |

| First prevalent screening, women age 50–52 | |

| Women screened | 10 000 |

| Recall for assessment | 700–100 |

| Invasive cancers found | 27–36 |

| Small invasive cancers found (<15 mm) | 15–20 |

| Carcinoma in situ | 4 |

| Benign surgical biopsies | 18–36 |

| Repeat (incident) screen, women aged 53–70 | |

| Women screened | 10 000 |

| Recall for assessment | 500–700 |

| Invasive cancers found | 31–42 |

| Small invasive cancers found (<15 mm) | 17–23 |

| Carcinoma in situ | 5 |

| Benign surgical biopsies | 10–20 |

Figure 7.4 PPV diagrams. (a) Prevalent screen showing more variable performance and (b) incident screens showing everyone performing well above the minimum standards.

Source: NHS Breast Screening Programme.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree