2Breast Unit, Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research, UK

Overview

- Approximately half of women with operable breast cancer who do not receive any systemic therapy will die from metastatic disease

- Randomised trials have shown that giving patients adjuvant hormone therapy, chemotherapy or specific immunotherapy significantly improves survival

- In patients who cancers overexpress HER2, trastuzumab has been shown to improve overall survival

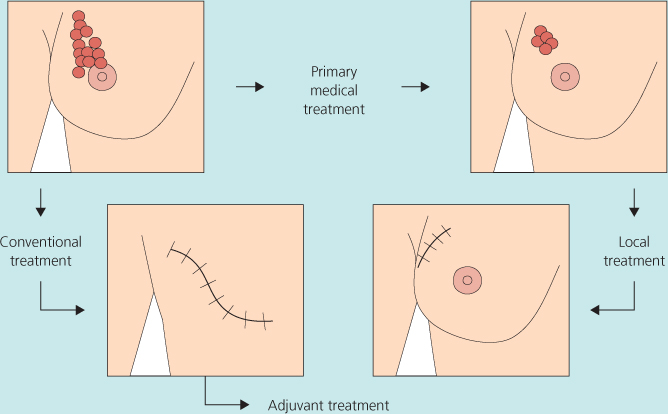

- Patients with larger tumours (Figure 11.1) can be treated initially with chemotherapy, with or without trastuzumab if HER2 positive or hormonal therapy, to make the cancer smaller and permit breast-conserving surgery

- Evidence demonstrates that adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy and hormonal agents should be delivered to the majority of patients with breast cancer

Mortality from breast cancer in the United Kingdom fell by over 15% in the first decade of the twenty-first century and continues to do so despite a rising incidence. This fall coincides with the widespread uptake of adjuvant systemic therapy and evidence of its survival benefit. The basis for this treatment is that more than half the women with operable breast cancer who receive local regional treatment alone die from metastatic disease, indicating the presence of micrometastases at initial clinical presentation. The major risk factors for the development of metastatic disease are axillary node involvement, a poor histological grade, large tumour size and histological evidence of lymphovascular invasion in and around the tumour site. The absence of oestrogen and/or progesterone receptors (ER/PgR) also carries an adverse prognosis at least for the first few years after diagnosis; the same used to be the case for the overexpression of the HER2 growth factor receptor, but prognosis in this subset has improved significantly with trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Systemic medical treatments, including endocrine therapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy with trastuzumab, are therefore crucial, along with surgery and radiotherapy to improve survival.

Systemic treatment may be given after (adjuvant) or before (neoadjuvant, primary or preoperative) locoregional treatment. The effectiveness of adjuvant and to a lesser extent neoadjuvant treatment has been shown in randomised clinical trials.

The key potential benefits of the neoadjuvant approach include:

- Downstaging a large primary, allowing conservative surgery rather than mastectomy in some patients (Figure 11.1).

- Using the tumour as an in vivo measure of responsiveness to treatment (although clinical benefit based on this approach remains to be demonstrated).

- Using short-term outcome measures in relatively small neoadjuvant trials to predict for long-term outcome in the adjuvant setting.

A central current issue in adjuvant medical therapies is how best to use molecular tumour markers including ER, PgR and HER2 to select the most appropriate treatment option for individual patients, and in particular to determine which patients do not benefit from chemotherapy, with all its inherent toxicities.

Endocrine Therapies

These include those described in the following sections.

Tamoxifen

- Is a partial oestrogen agonist (has antagonistic actions in breast cancers, but has agonist actions on endometrium, lipids and bone).

- Is effective at 20 mg/day with no gain from higher doses.

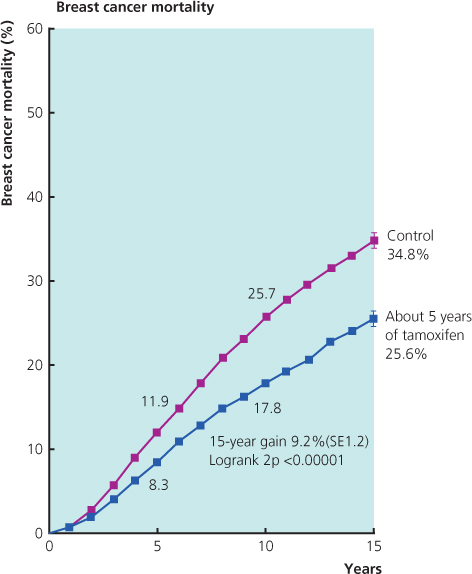

- Is effective in all age groups, including both premenopausal and postmenopausal women with ER-positive but not ER-negative cancers (Figure 11.2; Table 11.1).

- Is more effective when given for five years rather than two. Current evidence suggests there may be little additional benefit if taken for more than five years (Figure 11.3).

- Reduces risk of contralateral breast cancer by 40–50%.

- Is currently considered more effective when given after chemotherapy (when this is also indicated) rather than concurrently.

Table 11.1 About five years of tamoxifen versus not in ER-positive (or ER-unknown) disease by age: Event rate ratios.

| Breast cancer mortality/women | ||

| Deaths/women | ||

| Allocated tamoxifen | Adjusted control | |

| Age | Entry age 2p>0.01; NS | |

| <40 | 74/417 | 119/398 |

| (17.7%) | (29.9%) | |

| 40–49 | 173/1119 | 219/1139 |

| (15.5%) | (19.2%) | |

| 50–59 | 330/1591 | 394/1535 |

| (20.7%) | (25.7%) | |

| 60–69 | 379/1822 | 527/1789 |

| (20.8%) | (29.5%) | |

| ≥ 70 | 62/266 | 89/286 |

| (23.3%) | (31.1%) | |

*Data from Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (2005).

Figure 11.2 About five years of tamoxifen versus not in ER-positive (or ER-unknown) disease: 15-year probabilities of breast cancer mortality.

Figure 11.3 Results from NSABP-14 study that showed no benefit in extending tamoxifen treatment beyond five years.

Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs)

- In contrast to tamoxifen, these act by inhibiting oestrogen synthesis.

- Include the non-steroidal agents anastrozole and letrozole and the steroidal agent exemestane.

- Are effective only in postmenopausal women with ER-positive breast cancer.

- Have been shown to improve disease-free survival and metastatic-free survival with five years’ treatment compared with tamoxifen.

- Have been shown in one trial to improve survival very marginally compared with tamoxifen.

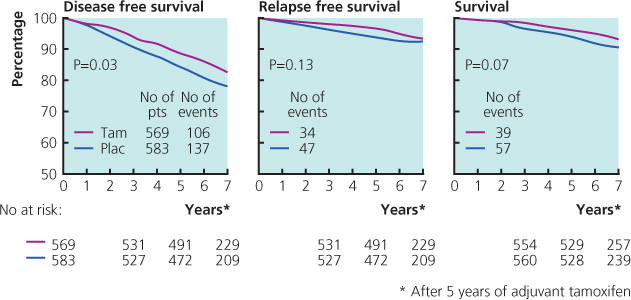

- Improve disease-free survival if patients are switched after two or three years of tamoxifen to an AI rather than continuing on tamoxifen.

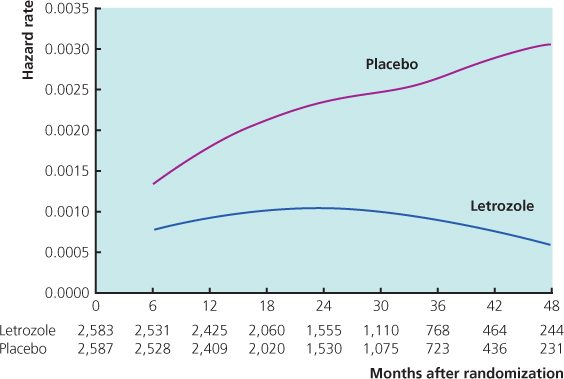

- Reduce the risk of recurrence when given for three to five years as extended adjuvant therapy in women still in remission after five years of tamoxifen and improve survival in node-positive patients (Figure 11.4).

- Reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer by a further 40–50% when given instead of, or after, tamoxifen (i.e. predicted total risk reduction around 75%).

Figure 11.4 Hazard rates for events in disease-free survival for patients randomised on MA.17 to either letrozole or placebo.

Oophorectomy or Ovarian Suppression with Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone (LHRH) Analogues

- Is of benefit only in premenopausal women with ER-positive cancer.

- May provide benefit in addition to chemotherapy in premenopausal women who continue to menstruate after chemotherapy (but confirmatory trials still underway). Whether they have benefit in addition to tamoxifen is uncertain.

Chemotherapy

Clinical trials have shown the following:

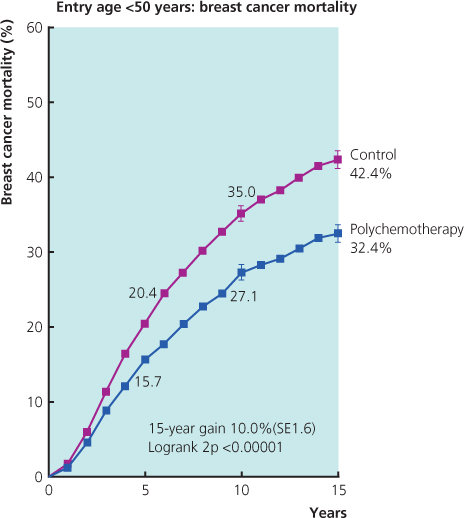

- The benefits of chemotherapy (Figure 11.5) depend on the biological subtype and benefits are greatest in women with ER-negative and/or HER2-positive cancers.

- The absolute benefit relates to absolute risk and therefore increases with increasing adverse risk factors such as axillary node involvement, increasing tumour size and grade 3 histology.

- Chemotherapy is not of benefit for many postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancers (the commonest subtype) and in particular for most of those with grade I or II, oestrogen-receptor-rich breast cancers, which are best treated with appropriate endocrine treatment, even when some axillary nodes are involved.

- A key challenge is to identify women with ER-positive HER2-negative breast cancers who receive hormone therapy who do not get a benefit from addition of chemotherapy. These include women with grade 3 tumours. Gene-expression assays may have an important role here.

- Anthracycline-containing combinations with doxorubicin or epirubicin are more effective than traditional CMF chemotherapy combinations.

- Taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) in addition to anthracyclines are of further benefit for women with ER-negative and/or HER2-positive cancers where absolute 10-year survival gains of more than 30% can be achieved in women at highest risk. Their additional value in ER-positive HER2-negative cancers (the major subgroup) is less certain.

Figure 11.5 Polychemotherapy versus not by age entry <50 or 50–69 years: 15-year probabilities of breast cancer mortality.

Side Effects: Endocrine Therapy (Table 11.2)

Table 11.2 Side effects of drugs used for adjuvant treatment.

| Chemotherary |

| Fatigue and lethargy |

| Alopecia (temporary*) |

| Nausea and vomiting |

| Induction of menopause |

| Risk of infection |

| Oral mucositis |

| Diarrhoea |

| Weight gain |

| Specific side effects of certain drugs |

| Oophorectomy/LHRH analogues |

| Induction of menopause |

| Vaginal dryness |

| Hot flashes |

| Osteoporosis |

| Tamoxifen |

| Venous thromboembolism |

| Hot flushes |

| Altered libido |

| Gastrointestinal upset |

| Vaginal discharge or dryness |

| Menstrual disturbance |

| Weight gain |

| Endometrial cancer (investigate any reported vaginal bleeding) |

| Aromatase inhibitors |

| Hot flushes (less than tamoxifen) |

| Joint and muscle pain |

| Osteoporosis |

| Fatigue |

| Vaginal dryness |

| Trastuzumab |

| Flu-like symptoms |

| Allergic reaction |

| Cardiac dysfunction |

| NB: usually none |

*Recently there have been reports of occasional permanent alopecia after docetaxel.

Tamoxifen may cause vaginal dryness or discharge, loss of libido and hot flushes, and these may have considerable impact on quality of life (so a significant percentage of patients stop treatment because of side effects). In postmenopausal women prolonged use of tamoxifen is associated with a three to four times increased incidence of endometrial cancer and a small increased risk of venous thromboembolism (similar to that associated with the contraceptive pill or hormone replacement therapy). Oophorectomy or LHRH analogues often cause severe menopausal symptoms and carry a markedly increased risk of bone loss, which can lead to osteoporosis.

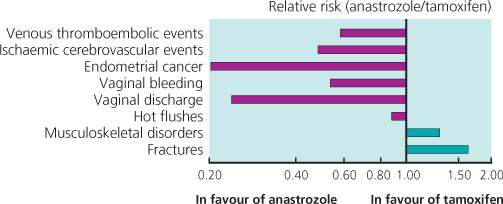

In postmenopausal women, trials have suggested that the aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane) cause fewer hot flushes and less vaginal discharge than tamoxifen. They are not associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer or venous thromboembolism. They are, however, associated with an increased risk of fractures, bone loss and osteoporosis. The main short-term problems of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are joint and muscle pains; these are often unpleasant but frequently settle with time. In a minority of patients they can be severe and treatment may need to be stopped or changed. Vaginal dryness is also common. A recent small study has shown that cognitive function is impaired to a greater extent with tamoxifen than with AIs in postmenopausal women, and in both groups there was some improvement when treatment was stopped after five years’ treatment.

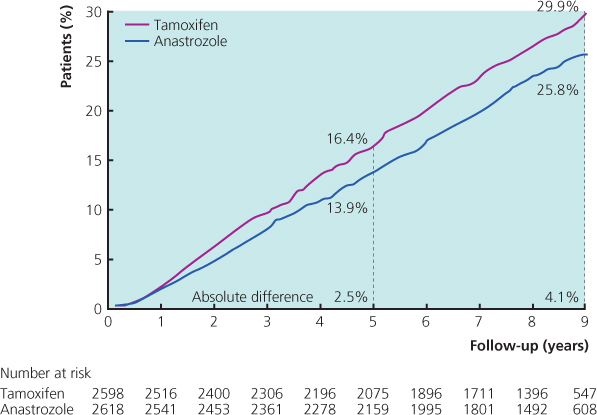

Overall in these trials there were more fractures, fewer thromboembolic events, fewer endometrial cancers and fewer other gynaecological problems with an AI compared with tamoxifen. An example of comparative risk in one of the trials is shown in Figure 11.6.

Management of Side Effects

All premenopausal women on tamoxifen or ovarian suppression and all postmenopausal women on AIs should have regular monitoring of bone mineral density and be advised to take regular moderate weight-bearing exercise. Those with mild/moderate osteopenia should also be recommended to take calcium/vitamin D supplements and those with significant bone loss or frank osteoporosis should also be started on a bisphosphonate. Trial data have shown that bone loss can be reduced markedly or prevented by prophylactic intravenous zoledronic acid given once every six months, but this has not yet become the standard of care.

First-line treatment for vaginal dryness with tamoxifen or ovarian suppression is with locally applied lubricants. Oestrogen creams and pessaries should be used with caution with Ais, since the small systemic oestrogenic spillover effect may potentially negate their efficacy. Therefore with AIs a non-oestrogenic cream such as Replens is another option, or treatment can be changed to tamoxifen.

Hot flushes are hard to treat. Neither clonidine nor evening primrose oil has been shown to be clinically effective in randomised trials. Megestrol acetate in a dose of 20 mg once or twice a day significantly improves flushing in 80% of patients; hot flushes often increase immediately after starting treatment and patients should be informed that treatment for two to four weeks is required to reduce the frequency of hot flushes. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are partially effective for hot flushes. Some SSRIs reduce the metabolism of tamoxifen to its most active metabolite, endoxifen, by inhibition of the cytochrome P450 enzyme, CYP2D6. When co-prescription of tamoxifen with an antidepressant is necessary, it has been recommended that preference should be given to antidepressants that show little or no inhibition of CYP2D6 such as venlafaxine or citalopram. However, the importance of CYP2D6 is not at all clear, with recent large studies casting doubt on its relevance in relation to tamoxifen effectiveness, so switching antidepressants may not be of any clinical value. Trials have shown that oestrogen replacement and tibolone therapy increase the risk of recurrence and so are not recommended.

Side Effects: Chemotherapy (Table 11.2)

Although hair loss is the most common concern of patients before starting chemotherapy, 80% report fatigue and lethargy as the most troublesome side effects. Alopecia caused by some chemotherapy regimens may be reduced by scalp cooling. Nausea and vomiting are unpleasant side effects, but can be controlled in most patients by appropriate antiemetic drugs, including the serotonin-3 antagonists granisetron and ondansetron (Table 11.3). These should be used as first-line treatment, even for moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. The introduction of the NK1 receptor antagonist aprepitant as second-line treatment has further improved the ability to prevent both acute and delayed emesis in patients receiving highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

Table 11.3 Anti-emetic regimens during chemotherapy.

| Standard anti-emetic schedules |

| Intravenous dexamethasone (4–8 mg) and intravenous granisetron (3 mg) or ondasetron (8 mg) before chemotherapy, and oral dexamethasone 4 mg two to three times daily to take home (for three days) |

| Additional treatment when needed |

| Oral granisetron (1 mg/day) or oral ondasetron (8 mg twice daily) for three to five days after chemotherapy. |

| Domperidone 20 mg four times daily (or by suppository) |

| Cyclizine 50 mg three times daily (or by infusional pump) |

| Lorazepam 1 mg twice daily (useful for anticipatory symptoms) |

| Aprepitant 125 mg 1 hour prior to chemotherapy on day 1, followed by 80 mg once daily on days 2 and 3 |

Haematological toxicity (particularly neutropenia) is a common side effect of most chemotherapy regimens, and neutropenic infection occurs in about 10% of patients, depending on the regimen. This requires urgent treatment with appropriate intravenous antibiotics and fluids. Trials have shown that dose reductions or delays in treatment may compromise efficacy, and for this reason haematopoietic support with GCSF should be used in patients in whom neutropenia would otherwise compromise treatment. Chemotherapy-induced ovarian suppression with loss of fertility is an important problem for younger women; the risk of this increases rapidly at age >35. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists are being investigated as ovarian protection against infertility.

Other side effects include oral mucositis, chemical conjunctivitis and diarrhoea. Some drugs have specific problems (for example fluid retention with docetaxel and neuropathy with either paclitaxel or docetaxel) and all chemotherapy requires specialist supervision.

Selection of Adjuvant Treatment (Table 11.4)

Table 11.4 Indications for treatment modalities.

| Treatment modality | Indication |

| Endocrine therapy | Any ER staining |

| Anti-HER2 therapy | ASCO/CAP HER2 positive[HER2 3+ >30% intense and complete staining (ICH) or FISH >2.2+] |

| In HER2-positive disease (with anti-HER2 therapy) | Trial evidence for trastuzumab is limited to use with or following chemotherapy |

| In triple-negative disease | Most patients |

| In ER-positive, HER2-negative disease* (with endocrine therapy) | Lower ER and/or PgR level |

| Grade 3 | |

| High proliferation rate | |

| Node positive (≥ 4 involved nodes) | |

| Extensive lymphovascular invasion | |

| Size >5 cm |

*Currently there is considerable uncertainty on relative risk factors for chemotherapy benefit in this large subgroup.

Modified from St Gallen (2009).

Choice of treatment depends on risk of relapse, potential benefits of different treatments, oestrogen-, progesterone- and HER2 receptor status, age, menopausal status and acceptability of treatment to the patient.

Endocrine Therapy

Until recently, tamoxifen was the most commonly used hormonal agent in the adjuvant setting in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. A major development in postmenopausal women has been the emergence of the so-called third-generation AIs (anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane), which all have a small but statistically significant efficacy benefit over tamoxifen. The AIs act by blocking the synthesis of oestrogen, which is mediated through the aromatase enzyme, in contrast to tamoxifen, which is an oestrogen receptor antagonist. The efficacy of AIs has been established only in postmenopausal women.

Results from Trials

In the ATAC (arimidex, tamoxifen, alone or in combination) trial involving around 9000 women, anastrozole achieved a small but significant disease-free survival (DFS) improvement at eight years with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.87 (95% CI 0.78–0.97) in the hormone receptor-positive group compared with tamoxifen (Figure 11.7). An earlier analysis had also shown superiority over the combination. In the most recent analysis at ten years, hazard ratios were similar to those in the previous reports. Anastrozole continued to be associated with a prolonged DFS, time to recurrence (TTR, absolute difference of 4.3% at ten years), reduced distant metastases and fewer contralateral breast cancers. However, there was still no significant difference in overall survival (HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.84–1.06).

Figure 11.7 Updated analysis of the ATAC trial, at a 100-month median follow-up: Kaplan-Meier prevalence curves for disease-free survival (DFS) in hormone receptor-positive patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree