Reduction of Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

Amanda Pratt

John M. Loiselle

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint dislocation is the displacement of the mandibular condyle from the mandibular fossa, rendering the patient unable to achieve reduction without assistance. It is an uncommon condition in children but may occur in adolescents. Due to the associated pain and anxiety, patients in the acute period typically present to the emergency department (ED) or to a dental or primary care office.

The procedure for reducing a temporomandibular joint dislocation has changed little since Hippocrates, who is generally credited with the earliest description of the technique.

The goal in treatment is to reduce the dislocation, restore function, and alleviate pain. The earlier the reduction is attempted, the greater the likelihood of success (1,2). Reduction is most frequently performed in the office or ED setting by a physician, dentist, or oral surgeon and is relatively uncomplicated, assuming that proper technique is followed.

Anatomy and Physiology

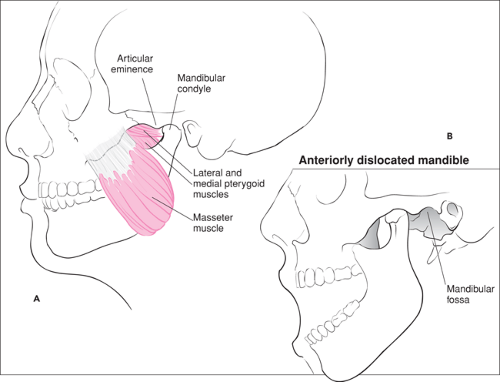

The temporomandibular joint consists of the head of the mandibular condyle sitting within the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone (Fig. 68.1A). The articular surfaces are lined by a synovial membrane and separated by a disk or meniscus composed of fibrous connective tissue. The structure of the joint allows for hinge, gliding, and side-to-side motions. The capsular ligament attaches to both the mandibular fossa and the neck of the condyle. Its laxity allows for the flexible movement of the joint. The joint is also supported by two ligaments on the medial surface, the sphenomandibular and stylomandibular ligaments, and one on the lateral surface, the temporomandibular ligament. Recurrent dislocation may be associated with excessive laxity in these ligaments, as occurs in Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndrome.

The lateral pterygoid muscle and several neck muscles are responsible for opening the jaw. Closure is controlled by the masseter, medial pterygoid, and temporalis muscles.

Acute dislocation of the temporomandibular joint occurs most frequently in an anterior direction, causing the mandibular condyle to become locked in front of the articular eminence (Fig. 68.1B). Dislocation can occur bilaterally or unilaterally. Spasms of the lateral pterygoid and temporalis muscles maintain the dislocation and often make reduction difficult. Conditions that predispose to dislocation include prior stretching of the joint capsule, a low articular eminence, increased tonicity of the muscles of mastication, and excessive ligamentous laxity.

A number of mechanisms are associated with anterior dislocation, including extreme mouth opening, as occurs during episodes of laughing, yawning, or vomiting, and prolonged mouth opening, as occurs with tonsillectomy or dental therapy (1,3). Dislocation also can occur as a result of convulsions, dystonic reactions, or trauma.

Although unusual, posterior and superior dislocations may be seen. Posterior dislocation is generally the result of trauma and often is associated with damage to the nearby auditory system. Disruption of the external auditory canal or fracture of the temporal plate is common (4). Superior dislocation occurs with severe trauma and is associated with fractures of the mandibular fossa. Lateral dislocations occur only with concomitant fractures of the mandibular body (5).

Indications

Patients with an acute anterior dislocation of the temporomandibular joint complain of severe pain in the preauricular

area. They present with an open mouth, a protruding mandible, and an inability to occlude the anterior teeth. A visible depression is evident in the preauricular area. In the case of a unilateral dislocation, the jaw will be displaced toward the unaffected side.

area. They present with an open mouth, a protruding mandible, and an inability to occlude the anterior teeth. A visible depression is evident in the preauricular area. In the case of a unilateral dislocation, the jaw will be displaced toward the unaffected side.

Figure 68.1 A. Anatomy of the temporomandibular joint. B. Anterior dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. |

Before reduction is attempted, radiographs should be obtained to confirm the dislocation and exclude any associated fractures. A panoramic view is considered best for this purpose, although transcranial, transpharyngeal, or transorbital temporomandibular joint views are generally adequate. A dislocation associated with a fracture of the mandibular condyle often requires open reduction and internal fixation. Referral to an oral surgeon is recommended in this situation.

Damage to the cartilage within the temporomandibular joint can produce a hemarthrosis and a subsequent subluxation but not a true dislocation of the mandible. Attempts at manual reduction will fail for obvious reasons and are contraindicated if this condition is recognized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree