Background

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of severe maternal morbidity and of preventable maternal mortality in the United States. The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative developed a comprehensive quality improvement tool kit for hemorrhage based on the national patient safety bundle for obstetric hemorrhage and noted promising results in pilot implementation projects.

Objective

We sought to determine whether these safety tools can be scaled up to reduce severe maternal morbidity in women with obstetric hemorrhage using a large maternal quality collaborative.

Study Design

We report on 99 collaborative hospitals (256,541 annual births) using a before-and-after model with 48 noncollaborative comparison hospitals (81,089 annual births) used to detect any systemic trends. Both groups participated in the California Maternal Data Center providing baseline and rapid-cycle data. Baseline period was the 48 months from January 2011 through December 2014. The collaborative started in January 2015 and the postintervention period was the 6 months from October 2015 through March 2016. We modified the Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement to include the mentor model whereby 20 pairs of nurse and physician mentors experienced in quality improvement gave additional support to small groups of 6-8 hospitals. The national hemorrhage safety bundle served as the template for quality improvement action. The main outcome measurement was the composite Centers for Disease Control and Prevention severe maternal morbidity measure, for both the target population of women with hemorrhage and the overall delivery population. The rate of adoption of bundle elements was used as an indicator of hospital engagement and intensity.

Results

Compared to baseline period, women with hemorrhage in collaborative hospitals experienced a 20.8% reduction in severe maternal morbidity while women in comparison hospitals had a 1.2% reduction ( P < .0001). Women in hospitals with prior hemorrhage collaborative experience experienced an even larger 28.6% reduction. Fewer mothers with transfusions accounted for two thirds of the reduction in collaborative hospitals and fewer procedures and medical complications, the remainder. The rate of severe maternal morbidity among all women in collaborative hospitals was 11.7% lower and women in hospitals with prior hemorrhage collaborative experience had a 17.5% reduction. Improved outcomes for women were noted in all hospital types (regional, medium, small, health maintenance organization, and nonhealth maintenance organization). Overall, 54% of hospitals completed 14 of 17 bundle elements, 76% reported regular unit-based drills, and 65% reported regular posthemorrhage debriefs. Higher rate of bundle adoption was associated with improvement of maternal morbidity only in hospitals with high initial rates of severe maternal morbidity.

Conclusion

We used an innovative collaborative quality improvement approach (mentor model) to scale up implementation of the national hemorrhage bundle. Participation in the collaborative was strongly associated with reductions in severe maternal morbidity among hemorrhage patients. Women in hospitals in their second collaborative had an even greater reduction in morbidity than those approaching the bundle for the first time, reinforcing the concept that quality improvement is a long-term and cumulative process.

Introduction

Obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the world and remains the cause of maternal mortality in the United States that has the greatest chance of preventability. Recent evidence indicates that the rate of obstetric hemorrhage is increasing in the United States and hemorrhage is by far the most frequent cause of severe maternal morbidity. Therefore, it has been the focus of worldwide research to find new treatments. But perhaps more importantly, there has also been an effort to better establish, disseminate, and implement a structured team approach for the care of a mother with hemorrhage. In California, a multidisciplinary task force developed a quality improvement tool kit of best practices and implementation strategies. This approach has been shown to be of benefit in individual hospitals and a health system and was one of the foundations for the National Partnership for Maternal Safety Consensus Bundle for Obstetric Hemorrhage. In the current project we seek to determine if this approach can reduce severe maternal morbidity from obstetric hemorrhage when scaled up to include >100 hospitals with a broad range of sizes and affiliations that collectively care for >250,000 births each year. The project aims to improve response to obstetric hemorrhage so that fewer mothers (both those with hemorrhage and overall) experience transfusions, major procedures, or serious medical complications.

Materials and Methods

Our study plan, the analysis, and this report were designed following the SQUIRE 2.0 standards for quality improvement research. For context, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) is a multidisciplinary multistakeholder quality collaborative based at Stanford University since 2006. CMQCC has a long track record of developing quality improvement tool kits comprising best practices, educational tools, and sample protocols, policies, and other implementation aides. Each tool kit was followed by ≥1 multihospital quality collaboratives to test the recommendations and materials. The CMQCC obstetric hemorrhage tool kit was first developed in 2010 and updated in 2015. Two learning collaboratives with 25-30 volunteer California hospitals were undertaken in 2011 and 2013. Subsequent key informant interviews with participants were used to design this statewide implementation project. The collaborative content followed the organization of the National Partnership for Maternal Safety Consensus Bundle for Obstetric Hemorrhage with 4 domains (readiness, recognition and prevention, response, reporting/systems improvement). Each of these domains has a series of recommended bundle elements.

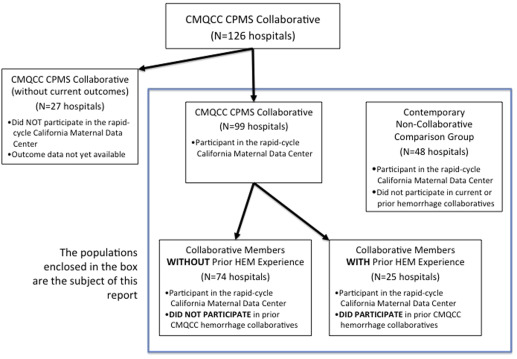

The California Partnership for Maternal Safety (CPMS) collaborative was established by CMQCC, in partnership and collaboration with the California Hospital Association/Hospital Quality Institute, the California district of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the California section of the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Invitations to participate in the state quality collaborative to reduce maternal morbidity were sent by each partner to all 245 California hospitals with maternity services. The CPMS collaborative began in January 2015 and lasted for 18 months. In all, 126 hospitals joined the collaborative in a staggered manner over the first 6 months. Of these hospitals, 99 participated in the California Maternal Data Center and this report will focus on these. The Figure describes the stages of hospital participation and analysis. The first year of each hospital’s participation was focused on obstetric hemorrhage. Baseline outcome data were collected for the 48 months from January 2011 through December 2014. The postintervention period was considered the last 6 months of the project from October 2015 through March 2016.

The implementation strategy was similar to our earlier multihospital quality collaboratives and was based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement that emphasizes data-driven Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, community of learning, at least 2 all-participant face-to-face meetings, and monthly check-in telephone calls. We found in our earlier experience with this model that as the number of participating hospitals increased >20 it was increasingly difficult to provide individual attention and the monthly telephone calls became less productive. To scale up to >100 hospitals while still retaining the key attributes of the breakthrough series approach, we used a modified approach. This was the mentor model wherein a physician and nurse pair with maternal quality improvement experience were matched with groups of 5-8 hospitals. The hospital groups were often geographic or system based. The mentors were not from the facilities they supported and served as facilitators leading the monthly telephone calls, providing small group leadership and personal accountability. A CMQCC staff member also supported the mentor groups and attended all telephone calls to coordinate and share lessons and ideas from all the groups. In-person full-day meetings for learning and sharing involving all hospital teams were held toward the beginning and the end of the project. Additionally, hospitals were encouraged to share resources and discussion on a collaborative electronic mailist list/resource sharing service.

A key feature of the collaborative was the use of the CMQCC Maternal Data Center for data collection of structure, process, and outcome measures. The maternal data center is a rapid-cycle system that minimizes data collection burden, designed in partnership with state agencies. The data center receives and automatically links birth certificate and hospital discharge diagnosis data files on a monthly basis, 45 days after the end of every month. The data center was used to: (1) collect outcome measures, including a baseline of 48 months; (2) provide a user-friendly interface for structure and process measure collection; and (3) display monthly progress against others in the collaborative. During this study, 147 California hospitals were actively submitting monthly data to the maternal data center. In all, 99 were in the CPMS collaborative and 48 were not. Given long delays and difficulties in data collection among the 25 CPMS collaborative member hospitals not actively participating in the maternal data center, this report is based solely on those 147 hospitals actively reporting ( Figure ). An important role for the 48 noncollaborative comparison hospitals was to identify whether there were any widespread external trends that could account for changes in severe maternal morbidity.

Outcome measures were designed to be collected automatically using the 2 linked administrative data sets for all hospitals. This allowed for simultaneous and prospective collection of data from the noncollaborative comparison hospitals. A collaborative-specific interface was created in the maternal data center to allow hospital teams to easily enter dates for bundle completion and process measures. In addition, hospital teams could follow their individual progress and compare to other deidentified hospitals in the collaborative. Hospitals were divided for an additional analysis into those that had participated in an earlier hemorrhage CMQCC and those that had not.

We had extensive prior experience with validation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) measure of severe maternal morbidity among California hospitals and its use for quality improvement projects. This measure is a collection of medical and surgical diagnosis and procedure codes that had an excess association with maternal death ( Table 1 ). We also collaborated with the CDC to revise the definition of severe maternal morbidity to include International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision diagnosis and procedure codes. In that project, preliminary analysis indicated that same-hospital rates of severe maternal morbidity were similar before and after the code transition.

| Severe maternal morbidity (CDC) | Obstetric hemorrhage | |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnoses | Procedures | Diagnoses and procedure |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Blood transfusion (except for sickle cell disease) | Antepartum hemorrhage |

| Acute renal failure | Cardio monitoring | Postpartum hemorrhage |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | Conversion of cardiac rhythm | Placenta previa |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | Hysterectomy | Abruptio placenta |

| Aneurysm | Operations on heart or pericardium | Blood transfusion (except for sickle cell disease) |

| Cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation | Temporary tracheostomy | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Ventilation | |

| Eclampsia | ||

| Heart failure during procedure or surgery | ||

| Internal injuries of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis | ||

| Intracranial injuries | ||

| Puerperal cerebral vascular disorders | ||

| Pulmonary edema | ||

| Severe anesthesia complications | ||

| Sepsis | ||

| Shock | ||

| Sickle cell anemia with crisis | ||

| Thrombotic embolism | ||

For this collaborative, the main outcome measure was the rate of severe maternal morbidity among our target population: those patients who had a diagnosis of obstetric hemorrhage. A secondary outcome was the rate of severe maternal morbidity among all maternity patients. Obstetric hemorrhage was defined as parturients with International Statistical Classification of Diseases versions 9 and 10 diagnosis codes for antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage, placenta previa, abruption placentae, or the procedure code for transfusion. A common issue with administrative data in maternity hospitalizations is undercoding. In our earlier hemorrhage collaboratives we noted that there was a large number of women who received transfusions without a diagnosis code for obstetric hemorrhage. Case reviews found that most of these cases were related to acute blood loss and not preexisting anemia. Therefore, we included in the definition of hemorrhage all parturients who had a procedure code for transfusion without an appropriate hemorrhage diagnosis code unless there was a concurrent diagnosis of sickle cell crisis. We had initially wanted to collect the total number of units of red blood cells transfused to emulate the earlier study of Shields et al but found that most hospitals had significant difficulty in accurately collecting the number of blood units even directly from the blood bank.

Table 2 lists the safety bundle elements used to assess adoption of the bundle. Hospital teams were asked to document the date the bundle element was completed and share with others in their group appropriate protocols and experiences. Progress on bundle adoption was discussed during the monthly mentor telephone check-ins. Additional independent verification of adoption was not performed. Earlier experience indicated that debriefs served as an important feedback loop to support protocol adoption and we initially asked hospital teams to collect the frequency of debriefs following significant hemorrhage. However, this proved challenging given the wide variation in hemorrhage frequency related to hospital size and the logistics of collecting every debrief form so this measure was not uniformly collected. For data accuracy assessments, the rates of hemorrhage and severe maternal morbidity were routinely screened using algorithms for missing values, nonsense values, and outliers. We also tracked the rate of obstetric hemorrhage over time as earlier studies noted an increase in the frequency of coding for hemorrhage with increased surveillance.

| Safety bundle elements (dates established or completed were reported) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Readiness domain | Recognition and prevention domain | Response domain |

| Hemorrhage cart/including instruction cards for intrauterine balloons and compression stitches | Assessment of hemorrhage risk (prenatal, admission, and other) (policy with time frames, mechanism for documentation) | Use of unit-standard, stage-based obstetrics hemorrhage emergency management plan with checklists |

| STAT access to hemorrhage medications (kit or equivalent) | Measurement of cumulative blood loss (formal and as quantitative as possible) | Support program for patients, families, and staff for all significant obstetric hemorrhages |

| Hemorrhage response team established (anesthesia, blood bank, advanced gynecological surgery, and other services) | Active management of third stage of labor (departmentwide protocol for oxytocin at birth) | Reporting and systems learning domain |

| Massive transfusion protocols established | Establish culture of huddles to plan for high-risk patients | |

| Emergency release protocol established for O-negative and uncross-matched units of RBC | Postevent debriefing to quickly assess what went well and what could have been improved (agreed upon leader, time frame, with documentation) | |

| Protocol for those who refuse blood products | Multidisciplinary reviews of all serious hemorrhages for system issues | |

| Unit education to protocols | Monitor outcomes and progress in perinatal QI committee | |

| Regular unit-based drills with debriefs for obstetric hemorrhage | ||

To assess whether outcome improvements seen during the collaborative were due to the interventions, we examined whether hospitals that showed improvement had higher rates of bundle element adoption than those that did not show improvement. In all, 25 hospitals had previously participated in 1 of 2 earlier pilot hemorrhage CMQCC. To account for possible confounding we performed a subanalysis of hospitals with and without prior hemorrhage collaborative experience. As the study groups were not randomized, it would be expected that certain hospital characteristics could be overrepresented or underrepresented in the collaborative group. When that was noted, sensitivity analysis was performed by reanalysis once hospitals with that characteristic were removed.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from Stanford University as the study host, and the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects for the use of the linked data set. All cases were deidentified fully before clinical data were shared with the study team.

In this before-and-after design, we examined whether the proportion of women with major complications differed in the new time period after the introduction of the hemorrhage quality improvement collaborative. As this is largely a descriptive study, only simple statistics were performed: χ 2 and t tests were used to assess the significance of rate changes from baseline to intervention periods. All descriptive and statistical analyses were performed using software (SAS, Version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Materials and Methods

Our study plan, the analysis, and this report were designed following the SQUIRE 2.0 standards for quality improvement research. For context, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) is a multidisciplinary multistakeholder quality collaborative based at Stanford University since 2006. CMQCC has a long track record of developing quality improvement tool kits comprising best practices, educational tools, and sample protocols, policies, and other implementation aides. Each tool kit was followed by ≥1 multihospital quality collaboratives to test the recommendations and materials. The CMQCC obstetric hemorrhage tool kit was first developed in 2010 and updated in 2015. Two learning collaboratives with 25-30 volunteer California hospitals were undertaken in 2011 and 2013. Subsequent key informant interviews with participants were used to design this statewide implementation project. The collaborative content followed the organization of the National Partnership for Maternal Safety Consensus Bundle for Obstetric Hemorrhage with 4 domains (readiness, recognition and prevention, response, reporting/systems improvement). Each of these domains has a series of recommended bundle elements.

The California Partnership for Maternal Safety (CPMS) collaborative was established by CMQCC, in partnership and collaboration with the California Hospital Association/Hospital Quality Institute, the California district of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the California section of the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Invitations to participate in the state quality collaborative to reduce maternal morbidity were sent by each partner to all 245 California hospitals with maternity services. The CPMS collaborative began in January 2015 and lasted for 18 months. In all, 126 hospitals joined the collaborative in a staggered manner over the first 6 months. Of these hospitals, 99 participated in the California Maternal Data Center and this report will focus on these. The Figure describes the stages of hospital participation and analysis. The first year of each hospital’s participation was focused on obstetric hemorrhage. Baseline outcome data were collected for the 48 months from January 2011 through December 2014. The postintervention period was considered the last 6 months of the project from October 2015 through March 2016.

The implementation strategy was similar to our earlier multihospital quality collaboratives and was based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement that emphasizes data-driven Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, community of learning, at least 2 all-participant face-to-face meetings, and monthly check-in telephone calls. We found in our earlier experience with this model that as the number of participating hospitals increased >20 it was increasingly difficult to provide individual attention and the monthly telephone calls became less productive. To scale up to >100 hospitals while still retaining the key attributes of the breakthrough series approach, we used a modified approach. This was the mentor model wherein a physician and nurse pair with maternal quality improvement experience were matched with groups of 5-8 hospitals. The hospital groups were often geographic or system based. The mentors were not from the facilities they supported and served as facilitators leading the monthly telephone calls, providing small group leadership and personal accountability. A CMQCC staff member also supported the mentor groups and attended all telephone calls to coordinate and share lessons and ideas from all the groups. In-person full-day meetings for learning and sharing involving all hospital teams were held toward the beginning and the end of the project. Additionally, hospitals were encouraged to share resources and discussion on a collaborative electronic mailist list/resource sharing service.

A key feature of the collaborative was the use of the CMQCC Maternal Data Center for data collection of structure, process, and outcome measures. The maternal data center is a rapid-cycle system that minimizes data collection burden, designed in partnership with state agencies. The data center receives and automatically links birth certificate and hospital discharge diagnosis data files on a monthly basis, 45 days after the end of every month. The data center was used to: (1) collect outcome measures, including a baseline of 48 months; (2) provide a user-friendly interface for structure and process measure collection; and (3) display monthly progress against others in the collaborative. During this study, 147 California hospitals were actively submitting monthly data to the maternal data center. In all, 99 were in the CPMS collaborative and 48 were not. Given long delays and difficulties in data collection among the 25 CPMS collaborative member hospitals not actively participating in the maternal data center, this report is based solely on those 147 hospitals actively reporting ( Figure ). An important role for the 48 noncollaborative comparison hospitals was to identify whether there were any widespread external trends that could account for changes in severe maternal morbidity.