Reconstruction of the Anterior Vagina for Prolapse

Mark D. Walters

Matthew D. Barber

DEFINITIONS

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse—Descent of the anterior vaginal wall. Most commonly, this would be due to bladder prolapse (cystocele: either central, paravaginal, or a combination). Higher-stage anterior vaginal wall prolapse will generally involve uterine or vaginal vault (if uterus is absent) descent. Occasionally, there might be anterior enterocele (hernia of peritoneum and possibly abdominal contents) after prior reconstructive surgery.

Arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis—The white line of the pelvic sidewall. This thickening of the pelvic sidewall fascia extends from the ischial spine posteriorly to the pubic tubercle anteriorly. It is the site of lateral attachment of the pubocervical fascia.

Paravaginal defect—When the pubocervical fascia becomes detached from, or torn just medial to, its lateral attachment to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (white line).

Pelvic organ prolapse—The descent of one or more of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (vaginal vault or cuff scar after hysterectomy). The presence of any such sign should be correlated with relevant prolapse symptoms. More commonly, this correlation would occur at the level of the hymen or beyond.

Pubocervical fascia—A trapezoid-shaped fascia that provides support for the anterior vagina under the bladder. It is attached superiorly to the pericervical ring, distally to the pubic ramus, and laterally to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (white line).

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse occurs commonly and may coexist with disorders of micturition. Mild anterior vaginal prolapse often occurs in parous women but usually presents few problems. As the prolapse progresses, symptoms may develop and worsen, and treatment becomes indicated. The anterior vaginal wall is the most common segment of the vagina to prolapse and the segment that is most likely to fail long term after surgical correction. This chapter reviews the anatomy and pathology of anterior vaginal wall prolapse, with and without stress incontinence, and describes methods of surgical repair.

TERMINOLOGY

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele) is defined as pathologic descent of the anterior vaginal wall and overlying bladder base. According to the International Continence Society (ICS) standardized terminology for prolapse grading, the term “anterior vaginal prolapse” is preferred to “cystocele.” This is because information obtained at the physical examination does not allow the exact identification of structures behind the anterior vaginal wall, although it usually is, in fact, the bladder. A more recent joint report on terminology by the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and International Continence Society (ICS) states that anterior vaginal wall prolapse is most commonly due to bladder prolapse (cystocele: either central, paravaginal, or a combination). Higher stage of anterior vaginal prolapse generally involves some amount of uterine or vaginal apex descent. Rare anterior enteroceles can also be found. Most gynecologists are generally comfortable with the terms cystocele, rectocele, vaginal vault prolapse, and enterocele. Coupled with the brevity of these terms and their clinical usage for up to 200 years, the inclusion of these terms is appropriate.

Some regard it as important to surgical strategy to differentiate between a central cystocele (central defect with loss of rugae due to stretching of the pubocervical and subvesical connective tissue and the vaginal wall) and a paravaginal defect (rugae preserved due to detachment of the lateral vagina from the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis). Surgical procedures for each of these types of anterior vaginal wall prolapse are presented, although data specifically addressing the comparative efficacy of these various repairs are scarce.

ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGY

The etiology of anterior vaginal wall prolapse is not completely understood, but it is probably multifactorial, with different factors implicated in prolapse in individual patients. Normal support for the vagina and adjacent pelvic organs is provided by the interaction of the pelvic muscles and connective tissue. The upper vagina rests on the levator plate and is stabilized by superior and lateral connective tissue attachments. The midvagina is attached to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (ATFP; white lines) on each side, and the apical portion of the anterior vagina is attached to the web of the endopelvic fascia, including pubocervical fascia, and the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Pathologic loss of lateral and/or apical support may occur with damage to or impairment of the pelvic muscles, connective tissue attachments, or both.

Nichols and Randall described two types of anterior vaginal prolapse: distension and displacement. Distension was thought to result from overstretching and attenuation of the anterior vaginal wall, caused by overdistention of the vagina associated with vaginal delivery or atrophic changes associated with aging and menopause. The distinguishing physical feature of this type was described as diminished or absent rugal folds of the anterior vaginal epithelium caused by thinning or loss of midline vaginal fascia. The other type of anterior vaginal prolapse—displacement—was attributed to pathologic detachment or elongation of the anterolateral vaginal supports to the ATFP. It may occur unilaterally or bilaterally and often coexists with some degree of distension cystocele, with urethral hypermobility, or with apical prolapse. Rugal folds may or may not be preserved.

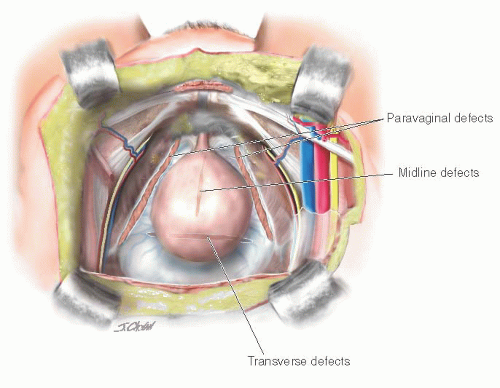

Another theory ascribes most cases of anterior vaginal prolapse to disruption or detachment of the lateral connective tissue attachments at the ATFP, resulting in a paravaginal fascial defect and corresponding to the displacement type discussed earlier. This was first described by White in 1909 and 1912, but disregarded until reported by Richardson in 1976. Richardson also described transverse defects, midline defects, and defects involving isolated loss of integrity of pubourethral ligaments. Transverse defects were said to occur when the pubocervical fascia separated from its insertion around the cervix, whereas midline defects represented an anteroposterior separation of the fascia between the bladder and the vagina. A contemporary conceptual representation of vaginal and paravaginal defects is shown in Figure 37.1.

There have been few systematic or comprehensive descriptions of anterior vaginal prolapse based on physical findings and correlated with findings at surgery to provide objective evidence for any of these theories of pathologic anatomy. In a study of 71 women with anterior vaginal wall prolapse and stress incontinence who underwent retropubic operations, DeLancey described paravaginal defects in 87% on the left and 89% on the right. The ATFP were usually attached to the pubic bone but detached from the ischial spine for a variable distance. The pubococcygeal muscle was visibly abnormal with localized or generalized atrophy in over half of the women.

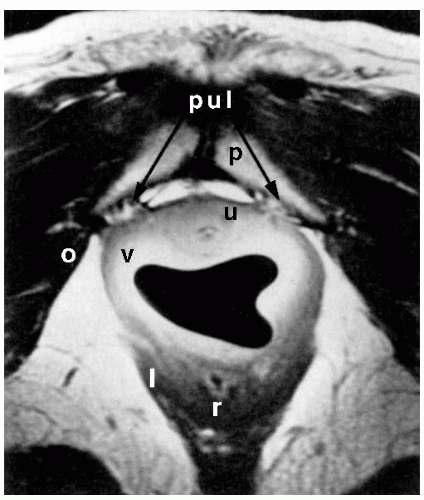

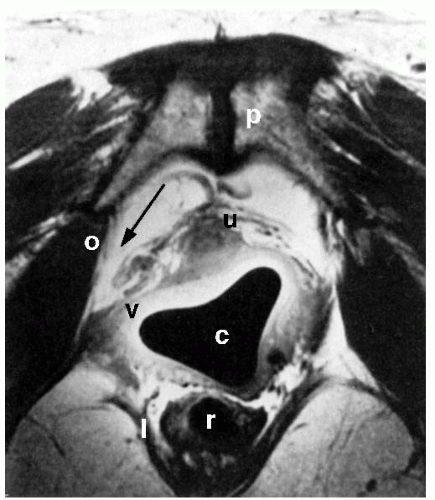

Improvements in pelvic imaging are leading to a greater understanding of normal pelvic anatomy and the structural and functional abnormalities associated with prolapse. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) holds great promise, with its excellent ability to differentiate soft tissues and its capacity for multiplanar imaging. The pelvic organs, pelvic muscles, and connective tissues can be identified easily with MRI. Various measurements can be made that may be associated with anterior vaginal prolapse or urinary incontinence, such as the urethrovesical angle, descent of the bladder base, quality of the levator muscles, and the relationship between the vagina and its lateral and apical connective tissue attachments. Aronson et al. used an endoluminal surface coil placed in the vagina to image pelvic anatomy with MRI and compared four continent nulliparous women with four incontinent women with anterior vaginal prolapse. Lateral vaginal attachments were identified in all continent women. In Figure 37.2, the “posterior pubourethral ligaments” (bilateral attachment of ATFP to posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis) are clearly seen. In the two subjects with clinically apparent paravaginal defects, lateral detachments were evident (Fig. 37.3). More recent studies based on MRI analysis and computer modeling suggest that apical support abnormalities are at least as important as, if not more important than, paravaginal defects; the degree of apical decent can explain about half of anterior wall descent. Other factors, such as levator muscle impairment, levator avulsion, greater anterior wall length, and widened levator hiatus, also contribute to anterior vaginal prolapse.

Anterior vaginal prolapse commonly coexists with stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Some features of pathophysiology may overlap, such as loss of anterior vaginal support with bladder-base descent and urethral hypermobility; other features, such as sphincteric dysfunction, may occur independent of vaginal and urethral support. The pathophysiology and surgical treatments of stress incontinence are covered more fully in Chapter 41.

EVALUATION

History

When evaluating women with pelvic organ prolapse or urinary or fecal incontinence, attention should be paid to all aspects of pelvic organ support. The reconstructive surgeon must determine the specific sites of damage for each patient, with the ultimate goal of restoring both anatomy and function. Patients with anterior vaginal prolapse complain of symptoms directly related to vaginal protrusion or of associated symptoms such as urinary incontinence or voiding difficulty. Symptoms related to prolapse may include the sensation of a vaginal mass or bulge, pelvic pressure, low back pain, and sexual difficulty. SUI commonly occurs in association with anterior vaginal prolapse, particularly when it is mild. In contrast, women with anterior vaginal prolapse that extends beyond the hymen are less likely to complain of stress incontinence and more likely to have obstructed voiding symptoms such as urinary hesitancy, intermittent flow, weak or prolonged stream, feeling of incomplete emptying, the need to manually reduce (splint) the prolapse to initiate or complete urination, and, in rare cases, urinary retention. The mechanism for this appears to be mechanical obstruction resulting from urethral kinking that occurs with progressively worsening anterior vaginal prolapse.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should be conducted with the patient in the lithotomy position, as for a routine pelvic examination. The examination is first performed with the patient supine. If physical findings do not correspond to symptoms or if the maximum extent of the prolapse cannot be confirmed, the woman is reexamined in the standing position.

The genitalia are inspected, and if no displacement is apparent, the labia are gently spread to expose the vestibule and hymen. The integrity of the perineal body is evaluated, and the approximate size of all prolapsed parts is assessed. A retractor or Sims speculum can be used to depress the posterior vagina to aid in visualizing the anterior vagina. After the resting examination, the patient is instructed to strain down forcefully or to cough vigorously. During this maneuver, the order of descent of the pelvic organs is noted, as is the relationship of the pelvic organs at the peak of straining.

It may be possible to differentiate lateral defects, identified as detachment or effacement of the lateral vaginal sulci, from central defects, seen as midline protrusion but with preservation of the lateral sulci, by using a pair of curved forceps placed in the anterolateral vaginal sulci directed toward the ischial spine. Bulging of the anterior vaginal wall in the midline between the forceps blades implies a midline defect; blunting or descent of the vaginal fornices on either side with straining suggests lateral paravaginal defects. Studies have shown that the physical examination technique to detect paravaginal defects is not particularly reliable or accurate. In a study by Barber et al. of 117 women with prolapse, the sensitivity of clinical examination to detect paravaginal defects was good (92%), yet the specificity was poor (52%); despite an unexpectedly high prevalence of paravaginal defects, the positive predictive value was poor (61%). Less than two thirds of women believed to have a paravaginal defect on physical examination were confirmed to possess the same at surgery. Another study by Whiteside et al. demonstrated poor reproducibility of clinical examination in detecting specific anterior vaginal wall defects. Thus, the clinical value of determining the location of midline, apical, and lateral paravaginal defects remains unknown.

Anterior vaginal wall descent usually represents bladder descent with or without concomitant urethral hypermobility. In 1.6% of women with anterior vaginal prolapse, an anterior enterocele mimics a cystocele on physical examination (Tulikangas et al., 2004). Other uncommon conditions, such as anterior vaginal cysts or myomas, can also mimic anterior vaginal prolapse.

Diagnostic Tests

After a careful history and physical examination, a few diagnostic tests are needed to evaluate patients with anterior vaginal prolapse. A urinalysis should be performed to evaluate for urinary tract infection if the patient complains of any lower urinary tract dysfunction. Hydronephrosis occurs in a small proportion of women with severe prolapse; however, even if identified, it usually does not change management in women for whom surgical repair is planned. Therefore, routine imaging of the kidneys and ureters is not necessary.

If urinary incontinence is present, further diagnostic testing is indicated to determine the cause of the incontinence. Urodynamic (simple or complex), endoscopic, or radiologic assessments of filling and voiding function are generally indicated only when symptoms of incontinence or voiding dysfunction are present. Even if no urologic symptoms are noted, voiding function should be assessed to evaluate for completeness of bladder emptying. This procedure usually involves a timed, measured void, followed by urethral catheterization or bladder ultrasound to measure postvoid residual urine volume.

In women with severe prolapse, it is important to check urethral function after the prolapse is repositioned. Women with severe prolapse may be paradoxically continent because of urethral kinking; when the prolapse is reduced, urethral dysfunction may be unmasked with occurrence of incontinence (occult stress incontinence). A pessary, vaginal retractor, or vaginal packing can be used to reduce the prolapse before office bladder filling or electronic urodynamic testing. If urinary leaking occurs with coughing or Valsalva maneuvers after reduction of the prolapse, the urethral sphincter may be incompetent, even if the patient is normally continent. This is reported to occur in 17% to 69% of women with stage III or IV prolapse. In this situation, the surgeon should choose an antiincontinence procedure in conjunction with anterior vaginal prolapse repair. If stress incontinence is not present even after reduction of the prolapse, an antiincontinence procedure probably is not indicated, although this is a subject of ongoing research.

SURGICAL REPAIR TECHNIQUES

General Considerations

The transvaginal operative procedures begin with the patient supine, with the legs elevated and abducted in stirrups and the buttocks placed just past the edge of the operating table. Antibiotics should be given within 60 minutes of incision to achieve minimal inhibitory concentrations in the skin and tissues by the time the incision is made. This typically means a first-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin) or combination regimens (500-mg metronidazole and 400-mg ciprofloxacin) if the patient has an allergy to penicillin. In general, all patients undergoing apical prolapse surgery are at moderate risk for thromboembolic events and require a prevention strategy. Low-dose unfractionated heparin (5,000 units every 12 hours) or low molecular weight heparins (e.g., 40-mg enoxaparin or 2,500 units of dalteparin), an intermittent pneumatic compression device, or a combination of these are recommended. Either form of heparin should be started 2 hours before surgery and the compression stockings placed on the patient in the operating room before incision. These treatment approaches should be continued until the patient is ambulatory.

Paravaginal Defect Repair: Transvaginal Approach

The aim of paravaginal defect repair for anterior vaginal prolapse is to reattach the detached lateral vagina to its normal place of attachment at the level of the ATFP. This can be accomplished using a vaginal or open or laparoscopic retropubic approach.

The preparation for vaginal paravaginal repair and for anterior colporrhaphy is similar. The abdomen, vagina, and perineum are sterilely prepped and draped, and a 16-French Foley catheter with a 10-mL balloon is inserted for easy identification of the bladder neck. A weighted speculum is placed into the vagina. Hemostatic solution (such as 0.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine) or saline may be injected below the epithelium along the midline of the anterior vaginal wall to decrease bleeding and to aid in dissection. If a vaginal hysterectomy has been performed, the incised apex of the anterior vaginal wall is grasped transversely with two Allis clamps and elevated. Otherwise, a transverse or diamond-shaped incision may be made in the vaginal epithelium near the apex. A third Allis clamp is placed about 2 cm below the posterior margin of the urethral meatus and pulled up. If a midurethral sling is to be done, then the incision is only made to the bladder neck. Additional Allis clamps may be placed in the midline between the urethra and the apex.

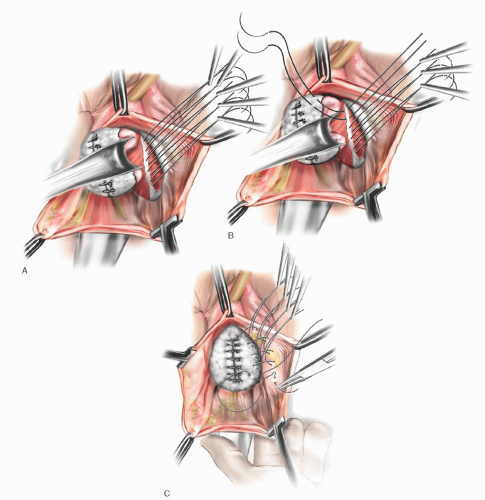

Marking sutures are placed on the anterior vaginal wall on each side of the urethrovesical junction, identified by the location of the Foley balloon after gentle traction is placed on the catheter. In patients who have had a hysterectomy, marking sutures are also placed at the vaginal apex. If a culdoplasty or apical suspension procedure is being performed, the stitches are placed but not tied until completion of the paravaginal repair and closure of the anterior vaginal wall. As for anterior colporrhaphy, vaginal flaps are developed by incising the vagina in the midline and dissecting the vaginal muscularis laterally. The dissection is performed bilaterally until a space—the paravaginal space—is developed between the vaginal wall and obturator internus muscle. Blunt dissection using the surgeon’s index finger is used to extend the space anteriorly along the ischiopubic rami, medially to the pubic symphysis, and laterally toward the ischial spine. If the defect is present and dissection is occurring in the appropriate plane, one should easily enter the retropubic space, visualizing retropubic and paravaginal adipose tissue. The ischial spine then can be palpated on each side. The ATFP coming off the spine can be followed to the back of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 37.4B). After dissection is complete, midline plication of the bladder adventitia is usually performed, either at this point or after placement and tying of the paravaginal sutures.

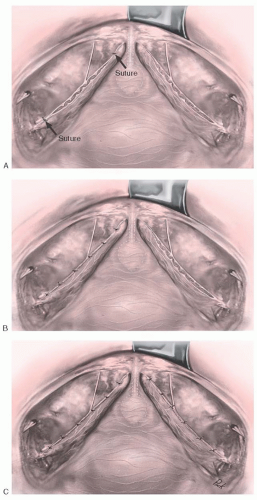

On the lateral pelvic sidewall, the obturator internus muscle and the ATFP are identified by palpation and then visualization. Retraction of the bladder and urethra medially is best accomplished with a Breisky-Navratil retractor, and posterior retraction could be provided with a lighted right-angle retractor. Using No. 0 nonabsorbable or delayed absorbable suture on a CT-2 needle, the first stitch is placed around the tissue of the white line just anterior to the ischial spine. Alternatively, a Capio device (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) works well to facilitate suture placement. If the white line is detached from the pelvic sidewall or clinically not felt to be durable, then the attachment should be to the fascia overlying the obturator internus muscle. The placement of subsequent sutures is aided by placing tension on the first suture. A series of three to six stitches are placed and held, working anteriorly along the white line from the ischial spine to the level of the urethrovesical junction (Fig. 37.4A). Starting with the most anterior stitch, the surgeon picks up the edge of the periurethral tissue (vaginal muscularis or pubocervical fascia) at the level of the urethrovesical junction and then the tissue from the undersurface of the vaginal flap at the previously marked sites. Subsequent stitches move posteriorly until the last stitch closest to the ischial spine is attached to the vagina nearest the apex, again using the previously placed marking sutures for guidance. Stitches in the vaginal wall must be placed carefully to allow adequate tissue for subsequent midline vaginal closure. After all the stitches are placed on one side, the same procedure is carried out on the other side. The stitches are then tied in order from the urethra to the apex, alternating from one side to the other. This repair is a three-point closure involving the vaginal epithelium, vaginal muscularis and endopelvic fascia (pubocervical fascia), and lateral pelvic sidewall at the ATFP (Fig. 37.4B, C). There must be tissue-to-tissue approximation between these structures. Suture bridges must be avoided by careful planning of suture placement. Vaginal tissue should not be trimmed until all the stitches are tied. The vaginal flaps are trimmed and closed with a running subcuticular or interlocking delayed absorbable suture.

Paravaginal Defect Repair: Retropubic Approach

The object of the retropubic paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus with its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the ATFP. The retropubic space is entered laparoscopically or through a small, low transverse incision, and the bladder and vagina are depressed and pulled medially to allow visualization of the lateral retropubic space, including the obturator internus and levator muscles, and the fossa containing the obturator neurovascular bundle. Blunt dissection can be carried dorsally from this point until the ischial spine is palpated. The ATFP is often visualized as a white band of tissue running over the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles from the back of the lower edge of the symphysis pubis toward the ischial spine. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina

off the ATFP or of the ATFP off the obturator internus muscle may be visualized (Fig. 37.5).

off the ATFP or of the ATFP off the obturator internus muscle may be visualized (Fig. 37.5).

The surgeon’s nondominant hand is inserted into the vagina. While gently retracting the vagina and bladder medially, the surgeon elevates the anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Starting near the vaginal apex, a suture is placed, first through the full thickness of the vagina (excluding the vaginal epithelium) and then deep into the obturator internus fascia or ATFP, 1 to 2 cm anterior to its origin at the ischial spine. After this first stitch is tied, additional (three to five) sutures are placed through the vaginal wall and overlying fascia and then into the obturator internus at about 1-cm intervals toward the pubic ramus (Fig. 37.5). The most distal sutures should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus, into the pubourethral ligament; alternatively,

Burch colposuspension sutures can be placed bilaterally at the level of the bladder neck and urethra if the patient has stress incontinence. No. 2-0 or 0 nonabsorbable suture on a mediumsized, tapered needle usually is used for the paravaginal repair.

Burch colposuspension sutures can be placed bilaterally at the level of the bladder neck and urethra if the patient has stress incontinence. No. 2-0 or 0 nonabsorbable suture on a mediumsized, tapered needle usually is used for the paravaginal repair.

This procedure leaves free space between the symphysis pubis and the proximal urethra but secure support so that rotational descent of the proximal urethra and bladder base is prevented with sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure. According to Turner-Warwick, it avoids overcorrection and fixation of the periurethral fascia, which might compromise the functional movements of the urethra and bladder base and lead to obstruction and voiding difficulty. This principle may explain why the paravaginal defect repair usually results in spontaneous voiding on the first or second postoperative day.

Anterior Colporrhaphy

The objective of anterior colporrhaphy is to plicate the layers of vaginal muscularis and adventitia overlying the bladder (“pubocervical fascia”) or to plicate and reattach the paravaginal tissue in such a way as to reduce the central protrusion of the bladder and vagina. Modifications of the technique depend on how lateral the dissection is carried, where the plicating sutures are placed, and whether additional layers (natural or synthetic grafts) are placed in the anterior vagina for extra support.

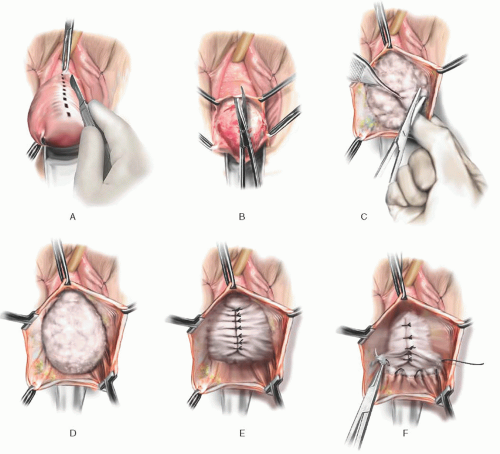

FIGURE 37.6 Classic anterior colporrhaphy. A: Initial midline anterior vaginal wall incision is demonstrated. B: The midline incision is extended using scissors. C:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|