Psychological Development

Elizabeth M. Ozer and Charles E. Irwin Jr.

PSYCHOLOGICAL CHANGES

Specific behavioral changes are associated with puberty and its timing.1-3 Androgens have been implicated as the cause of many of the changes associated with adolescence.4,5 Family relationships undergo a transformation during puberty.6,7 During peak height velocity (Tanner and Marshall sexual maturity rating [SMR] 3–4), boys experience more conflict with their parents, especially their mothers. This conflict tends to subside after completion of puberty, with mothers deferring more to their sons. Girls experience conflict with their mothers, and girls report decreased contact with their fathers. Hormones have been implicated as the cause of many of the behavior changes associated with normal and abnormal adolescence. Sexual behavior is associated with changes in androgens.8 Boys, with rising levels of testosterone, initiate coitus, and they are reported to be more impatient, aggressive, and irritable. For girls, an increase in masturbatory activity is associated with rising levels of androgens.

Specific psychosocial effects have been correlated with timing of pubertal maturation.2 Earlier maturation for girls is associated with greater dissatisfaction with physical characteristics, lower self-esteem, and general unhappiness. Early-developing girls receive less recognition from same-sex peers and tend to associate with older adolescents. The early-maturing girl shows increased interest in sexuality, early identity crises, greater interest in independence and decision-making, and more problem behavior in school with decreased interest in academic activities.9,10

For boys, early pubertal maturation is also associated with an increased tendency to initiate coitus. Late pubertal development in boys may be associated with adverse psychological effects. Late-developing boys may exhibit a more negative self-concept and body image with an increased frequency of identity crises than other same-aged boys of normal development.

For both girls and boys, late physical maturation appears to be protective for initiation of most risky behaviors. The social environment tends to provide more guidance and support for these physically immature adolescents.9

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

While adolescence is often characterized as a period of psychological turmoil, most adolescents successfully navigate the important transitions of this period in the life cycle.11-13 The growing field of positive youth development has focused on developing personal, environmental, and social assets that enable successful transition from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood.14,15 Despite adversity, many adolescents are surprisingly resilient.13 Most adolescents are attached to their families and communities, succeed in school, and traverse their teen/emerging adult years without serious problems.14

The adolescent is confronted with a series of psychological changes that, if mastered, allow for optimal functioning as an adult. An understanding of psychological development in adolescence enables the clinician to assess whether psychosocial development of the teenager is normal as well as helps the clinician to be an effective communicator with teenagers.11,15 Successful psychological development during adolescence involves developing competence in a number of realms: cognitive, moral, emotional, and social.

1. Cognitive development, or the changes in how adolescents think, reason, and understand, are dramatic.16,17 During the stages of adolescence, teenagers evolve from concrete thinkers to becoming able to think abstractly and apply hypothetical concepts (formal operational thinking). These changes are generally not complete until early adulthood. Becoming cognitively competent involves the ability to reason, problem solve, think abstractly and reflect, and plan for the future.

2. Moral development refers to how adolescents construct right and wrong.17 Cognitive development helps lay the groundwork for the ability to engage in moral reasoning and prosocial behavior such as caring for others and helping in the family and community.

3. Emotional development involves the development of a sense of identity, a central task of adolescence.18,19 A sense of identity involves an individual’s self-concept, or beliefs about himself or herself, and self-esteem, how the individual feels about his or her self-concept.

4. Social development refers to how teens relate to others in their peer group, family, school, work, and community environments.18,19

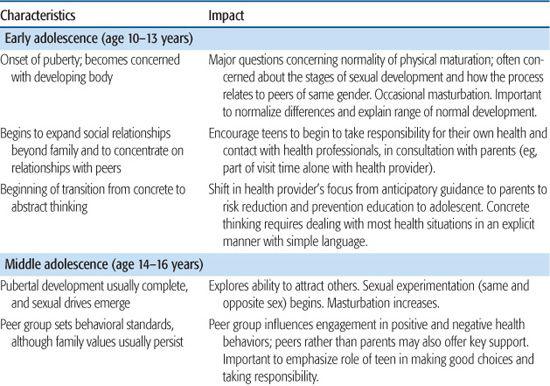

Normal development of the stages of adolescence and their associated impact on the adolescent and on delivery of health services are presented in Table 66-1.

During early adolescence (ages 10–13 years), teens are focused on their developing bodies, the peer group becomes increasingly important with concerns about acceptance and conformity, and individuals start to experiment with new behavior. Teens are transitioning from concrete to abstract thinking, and they have not yet developed the socioemotional competencies of self-regulation. The combination of these characteristics can lead to risky attitudes and behavior.9,10

Middle adolescence (ages 14–16 years) is characterized by the emergence of formal operational thinking with new cognitive competencies such as changes in information processing, perspective taking, and reflection. Adolescents are now able to understand complex concepts, which often leads to a questioning of the thinking and behavior of adults. This is often the time of greatest conflict with parents, especially over independence. There begins to be a shift from the egocentric world of the early adolescent to the more sociocentric world of the middle and late adolescent. Adolescents may contemplate more abstract concepts related to moral development, such as the law and justice. The ability to think abstractly also allows for reflection in the emotional realm, and focus shifts from same-sex relationships to dating. While more mature thought processes begin to modulate impulsive behavior, risky health behaviors are of major concern in middle adolescence as peer norms to engage in certain risky behavior (eg, substances, sexual activity) increases and individuals make more independent choices.

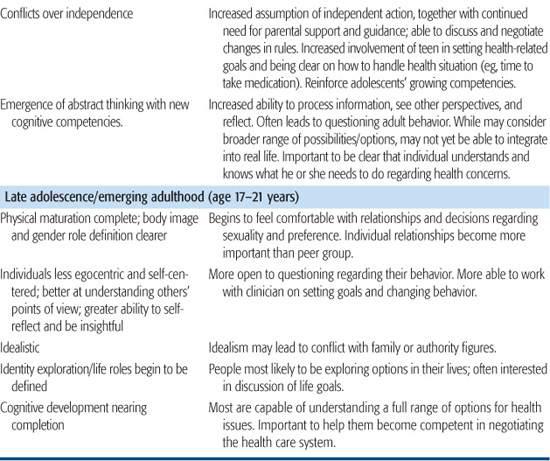

Late adolescence has traditionally been defined as ages 17 to 21. A more recent concept in the development of late adolescence/young adults is the theory of emerging adulthood.20,21 This focuses on the years from about age 18 to 25, recognizing those years as distinct from the preceding adolescent years as well as the young adult years that follow. The phases of late adolescence/emerging adulthood are characterized by identity exploration—a time for exploring possibilities in life in many areas, including love and work. Consistent with this task, there is increased cognitive ability for self-reflection and insight. This is also the time when individuals begin to define a functional role in society. The new emergence of a sociocentric view of the world with a strong sense of altruism may lead to conflict with family and society around moral and ethical issues rather than the egocentric issues of early adolescence. While individuals continue to become less self-centered, late adolescence/emerging adulthood is a self-focused time of life when people often have few obligations to others and substantial autonomy in terms of their lives.

Within the health practice setting, clinicians can support these developmental processes through raising adolescents’ awareness of their developing strengths across developmental realms and encouraging adolescents to take responsibility for the role they can play in their own health and well-being. Clinicians can help adolescents make better health decisions by involving them in their own health management; helping them see that they have a range of options; and encouraging parents, when appropriate, to decrease their monitoring of clinical management issues. Families play a critical role in successful development during adolescence by facilitating a graduated increase in independence and the associated responsibilities. Laying this groundwork becomes especially important in late adolescence/emerging adulthood when teens typically move out of their parents’ home and begin to seek their own health care.22,23

Table 66-1. Biopsychosocial Development during Adolescence/Emerging Adulthood

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES DURING ADOLESCENCE

The supportive social environment of the child undergoes significant changes during adolescence, with the family providing less supervision and more freedom of choices, which increases the opportunity for initiation of health-damaging habits. Schools at the secondary level are unstructured and impersonal. These institutions generally provide less supervision and support than was provided in the elementary school setting. Work environments for older adolescents provide less supervision than schools and little guidance about career choices. The changing socioeconomic context of families has consistently resulted in a small group of adolescents being raised in extreme poverty and most adolescents being raised in families with 2 working parents. Adolescents and young adults (12–24 years old) continue to represent the largest cohort of the population without health insurance, thereby further limiting access to health care.24

The law may further restrict access to health care, with most states requiring parental consent for medical care for children younger than 18 years of age. The Mature Minor Doctrine generally allows adolescents to seek health care independently if they are able to understand the risks and benefits of the proposed diagnostic assessment and treatment (see Chapter 9). This doctrine may also be used when adolescents present with an emergency and a delay in treatment would be detrimental to their well-being. Emancipated minors (as defined by living away from home, no longer subject to parental authority, economically self-sufficient, married, or members of the military service) may consent to their own health care. In most states, adolescents may seek care without parental permission for diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections. Also, many states allow adolescents to seek care and receive treatment without parental permission for other sensitive issues such as pregnancy, contraception, substance abuse, and some mental health problems.25,26

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree