Psychological Aspects of Pelvic Surgery

Betty Ruth Speir

DEFINITIONS

Anxiety—A feeling of apprehension, uncertainty, and fear without apparent stimulus and associated with physiologic changes (tachycardia, sweating, tremor, etc.).

Grief—The normal emotional response to an external and consciously recognized loss; it is self-limited, gradually subsiding within a reasonable time.

Insanity—Mental derangement or disorder. The term is a social and legal rather than medical one and indicates a condition that renders the affected person unfit to enjoy liberty of action because of the unreliability of his or her behavior with concomitant danger to self and others.

Regression—A return to a former or earlier state; a subsidence of symptoms or of a disease process; the turning backward of the libido to an early fixation at infantile levels because of inability to function in terms of reality.

Ethnicity—Ethnicity is a socially defined category based on common culture or nationality. Ethnicity can, but does not have to, include common ancestry.

Iatrogenic injury—An inadvertent adverse effect or complication resulting from medical treatment or “originating from a physician.”

Gender identity—Gender identity refers to a person’s private sense of, and subjective experience of, the person’s own gender.

Psychodynamics—Psychodynamics is the theory and systematic study of the psychological forces that underlie human behavior.

Vaginismus—Vaginismus is vaginal tightness causing discomfort, burning, pain, penetration problems, or complete inability to have intercourse.

Robotics—Robotic surgery is a technique in which a surgeon performs surgery using a computer that remotely controls very small instruments attached to a robot.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroscientific research over the past decade continues to validate the oneness of the psyche and the soma (Fig. 3.1). Gynecologic surgery, in particular, does not simply alter the soma, but temporarily and sometimes permanently alters the psyche of the patient. The modern gynecologist needs to be more than a skilled technician: he or she must be willing and able to identify the potential psychological effects of the surgery performed and must be prepared with the knowledge and skills to address these effects with the patient.

Sir William Osler taught, “The good physician knows the disease the patient has. The great surgeon knows the patient who has the disease.”

The technologic revolution has presented today’s surgeon with a vast array of sophisticated equipment. In capable hands, miraculous surgical feats can be performed on a woman’s body, but at what cost to her psychological self? The removal or reconstruction of diseased or dysfunctional anatomy may set off a chain reaction of parallel events in a woman’s psyche.

For a surgeon, the gynecologic operation may be a quotidian event of usually simple dimension. For the patient, however, each procedure is a unique and intimidating experience. Her sense of well-being and health may be threatened. She may lose control over her body for some indefinite period of time. She may perceive the planned procedure as temporarily or even permanently affecting her sexual identity.

As complicated procedures become routine, the surgeon risks losing perspective about the impact of surgery on the life of the individual woman. The patient who experiences ablative genital (or breast) surgery is strongly influenced by her emotions. These vary in degree but are usually cumulative. As the patient passes through the presurgical, surgical, and postsurgical experiences, she may be stressed beyond her capacity to compensate. If help is not available to facilitate emotional healing and rehabilitation, permanent psychological damage may result.

The majority of women do heal and take up their lives, raise their children, work at their jobs, and relate well to their husbands or lovers. For them, the healing interval is relatively quick, and the stress is modest. Do not underestimate what can be learned from this psychologically healthy segment of women patients. In the 1940s, Abraham Maslow studied people with exceptional mental health to develop his hierarchy of needs theory. He discovered that these people’s potential had never been weakened by negative thinking, a defeatist outlook, or a destructive self-image. “The rest of us,” he declared, “fixate at a lower level because someone or something has implanted notions of limitations.”

Once you become cognizant of the success statistics in your own patient population, you may discover why most women recover after gynecologic surgery to zestfully reembrace life, whereas others begin to slowly turn away from its possibilities.

It will never be enough for a surgeon to be a trained mechanic, able only to diagnose and repair. He or she must also be prepared to predict, recognize, and begin treatment of the psychological consequences of gynecologic disorders. This chapter is designed to help surgeons and other physicians better understand the female perspective and to use that knowledge to facilitate multidimensional healing.

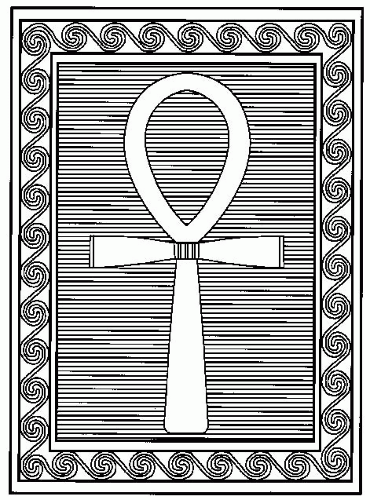

ANKH

The ansate cross, Egyptian emblem of generation, symbol for life and soul and eternity, is a mark universally designated to depict femaleness (Fig. 3.2). By using this hieroglyph, modern scientists continue an ancient tradition of respect and reverence for women. Within the inner sanctum of every woman’s mind lie symbols that are powerful and personal. These feminine

identity markers are guarded and guided by her instincts, and no surgeon can successfully maneuver in this labyrinth of psychological and psychosexual emotion and cause no harm unless the female patient acts as a guide.

identity markers are guarded and guided by her instincts, and no surgeon can successfully maneuver in this labyrinth of psychological and psychosexual emotion and cause no harm unless the female patient acts as a guide.

Egyptian writings from almost 4,000 years ago in the Kahun Papyrus depict the uterus as having an important and powerful effect on mental life. Current research tends to agree with the ancient scribes. The uterus has great symbolic value for many modern women, too. Beginning with the rite of passage called menstruation, a strong invisible bond is formed between a woman and her body. Her biologic clock has been set. For the next 40 years or so, she will be reminded each month that she is a woman, and menstruation is regarded by many as palpable proof of their femininity.

Others believe that menstruation is part of a natural cleansing cycle that purges the body of poisons that accumulate during the month. They know from experience that the premenstrual symptoms of edema, bloating, headaches, and emotional tension will be washed away in the tide of their monthly flow.

For some, the rhythm of the menstrual cycle is used as a way to time and order their lives. Like the phases of the moon, this cycle bestows a sense of routine, regularity, and predictability that has emotional significance. With the onset of menstruation, a woman is forever changed. Surgical removal of any of the reproductive organs will change her again, but how?

The effect of a woman’s menstrual cycle on many medical conditions is well documented. Medical suppression of ovulation is commonly used as a way to evaluate and treat such chronic conditions as migraine, epilepsy, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, and diabetes. Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other leading institutions has shown “how nerves, molecules and hormones connect the brain and immune system, how the immune system signals the brain and affects our emotions, and documents how our brain can signal the immune system, making us more vulnerable to illnesses.” What we have known intuitively is now understood scientifically. Hormones secreted during a woman’s menstrual cycle affect her mood. Could the decline of these hormones during the natural aging process contribute to dementia? The future is alive with fascinating neuroscientific and neuroimmunomodulation elucidation, but today’s woman is backlit by the skepticism of some scientists. Her concerns about her body and the way it will work after surgery are immediate and quite often, heart wrenching.

A woman about to undergo a hysterectomy might wonder if her lover will be able to detect the absence of her uterus. After the surgery, will she be thought of as less of a woman? Will her partner abandon her for someone who is still complete, either in the sense of being able to offer the possibility of a child or complete in the sense of having experienced no unnatural surgical transformations?

Will orgasm be as pleasurable for her after the surgery? For many women, the uterus has symbolic significance as a sexual organ. The uterus contracts during orgasm. Some women perceive this as most pleasurable. If the patient believes the uterus is essential to sexual response, then, in fact, it often becomes so, and women with this mindset may become sexually dysfunctional when it is removed.

Once the procedure is accomplished, will she still look and sound like a woman, or will she become noticeably more masculine? For others, the uterus is closely tied to feelings of attractiveness and sexual desirability. To a few women, removal of the uterus or ovaries or both constitutes a desexing, a permanent destruction of female identity and function. Sadly, certain members of the medical community as well as the feminist community perpetuate this notion and increase the attendant fear when they refer to women who must have their ovaries removed as “castrates.”

Some women become distressed when they learn they must deal with the certainty of absolute sterility. For those who choose motherhood, the uterus, ovaries, breasts, and vagina work in harmony with other factors to attract a necessary mate and get down to the business of creating new life. These organs are vital to the sexual and reproductive aspects of a woman’s life; thus, impending loss of these physical structures because of disease or dysfunction sometimes creates deep angst that must be resolved before surgery is attempted. Many women who have all the children they want and who do not wish to get pregnant again are still sometimes disturbed by the finality of the decision. The gynecologist should assure these maternal women that, although they will no longer be able to conceive a child, the powerful urge to create will never leave them. In time, they will learn to direct this primal energy into other areas of their lives and be immensely satisfied with the results. Studies such as the Ethnicity, Needs, and Decisions of Women project (ENDOW), a 5-year, three-phase, multicenter collaboration, are focusing on many of these issues and will help the gynecologist better understand the patient.

Today’s modern woman, for the most part, is an avid information seeker. She surfs the Internet, buys the latest books, reads magazine articles, and conducts in-depth interviews with peers who have experienced similar gynecologic problems. A certain proportion of the harvested material is useful to her and perhaps even illuminating for the physician, but unfortunately, some of the sources are inherently flawed, prejudicial, illogical, or without scientific basis. It is the physician’s responsibility to separate the grains of truth from the chaff. All the information the patient has gathered represents her attempt to prepare herself psychologically for the ordeal ahead, and she must never be condemned or made to feel small for trying to protect herself.

For the gynecologist, it is not necessary, or even possible, to change a patient’s basic attitude or feelings. It is, however, vital to acknowledge them. The right information, reassurance, and support usually quickly modify many negative factors and lead to a healthier attitude and understanding of the surgical process. It is crucial that the patient be allowed to vent her anxiety and give voice to her fears.

COMMUNICATION

Patients in General

Diplomats the world over understand the significance of effective communication. Indeed, the prospect for world peace depends on their ability to interact efficiently. A female patient’s psychological bearing before, during, and after the gynecologic procedure can depend on the communication techniques used by her physician. You must establish rapport, speak of the real and present danger to her health, and then elaborate on your plans to protect her.

Whenever possible, provide pleasant surroundings where you and your patient can comfortably hold a private conversation. Push all other thoughts out of your mind. These few minutes belong exclusively to her, and the quality of the time you spend actively communicating will pay healthy dividends for you both.

Whether explaining the simplicity of a needle-directed breast biopsy or the intricacies of hysterectomy, you must be able to highlight the technical details of the procedure and its postsurgical realities in a nonthreatening but utterly

truthful manner. Begin the presentation using simple but thorough explanations and examples of the procedures. Your patient will let you know how much information she can or wishes to process by the questions she asks.

truthful manner. Begin the presentation using simple but thorough explanations and examples of the procedures. Your patient will let you know how much information she can or wishes to process by the questions she asks.

Your patient needs confidence in your technical ability, to know that her problem is being taken seriously and that you are qualified to competently help her cope with all of the ramifications of this new experience.

Dealing with the patient’s feelings is not usually difficult if the surgeon accepts the viewpoint that many of the patient’s emotions are part of the gynecologic situation. To the physician, the presurgical tension is predictable, familiar, transient, and simply comes with the territory; but to each new patient, it epitomizes an unfamiliar, dramatic, and life-altering experience.

To interpret the patient’s true feelings, simply listen to her. Listening well is both an art and a skill, and the surgeon who cares about the patient’s complete health as well as her quick recovery works diligently to hone a sharp edge on this valuable tool. Listen and you will hear the woman give a name to her most profound doubts and fears. Repeat her words so that you are absolutely certain you understand what she said, and so that she is absolutely assured that you are listening to her.

Begin the communication process by finding out what the patient perceives will be done to her body and why the procedure is necessary. Find out what she believes the consequences of the surgery will be. How does she think the surgery will impact her life? As she discusses the implications of her decision, her knowledge, fears, and biases will emerge. At this point, you should be able to supplement the patient’s perspective with appropriate explanations about anatomy, physiology, and pathology. After this, it is time to describe in detail the usual preoperative, operative, and postoperative routines. Address the patient’s questions and fears in as many ways as it takes for her to become confident that she understands what will happen to her.

Carefully explain what you are going to do to help her. If she wants or needs to know, describe the common physical sensations, bandages, incisions, catheters, tubing, and medications that are associated with her particular procedure. Define the patient’s role in her own convalescence and recovery. Give her a general timetable for how long she will feel discomfort and need to use pain medication, when she will be ambulatory, and finally, when she will be discharged from the hospital or outpatient center.

Relate the most common complications that might occur as the result of her surgery. Injuries that might affect the quality of her life, even temporarily, should never come as a postsurgical surprise, nor should they be glossed over during the signing of the consent forms. Every patient wants to trust the doctor.

Informed Consent/Ethical Issues

Tell a patient that she has the option of robotic surgery and you’ll probably get an exuberant response. “A robot! How cool is that! What’s its name?” Angelos, who runs the first surgical ethics program in the United States, understands that most people automatically think new anything is better than old everything and that robots are magnificent manifestations of technology. He knows that many surgeons prefer to walk on the cutting edge, too, but in reality, is this a slippery ethical slope?

Before a proper informed decision can be made, the patient should know that in the beginning, a new procedure or system has fewer data on outcomes on which to base a decision, and the patient’s surgeon should be honest about his or her level of experience. The ultimate decision must be based on what benefits the patient is expecting from the procedure and which choice is the most likely to produce that benefit.

Iatrogenic injury remains the most common cause of lower urinary tract trauma. An understanding of the prevention, recognition, and treatment of urologic complications is important for every surgeon performing major pelvic surgery. Injury to a woman’s genitourinary system may take 10 to 20 years to develop full-blown symptoms, about the same time line as from multiple childbirths, but it remains a possibility. Physicians, however, disagree on whether or not to tell the patient that, because of damage to the pelvic nerves or pelvic supportive structures, urinary incontinence after hysterectomy could be a long-term adverse effect. Only 4% of the hysterectomies performed are for relief from symptoms of incontinence.

Complications such as the formation of adhesions may occur in as many as 55% of patients after gynecologic surgery. These adhesions can become a critical issue from the standpoint of reproductive potential. Their presence is also strongly associated with pelvic pain, abnormal bowel function, and small bowel obstruction.

The mentally competent patient has a moral, legal, and ethical right to make an intelligent informed decision and can only do it if she is privy to all of the available facts concerning her situation. It is essential for her to be involved in the decision-making processes, because the more committed she is to the proposed treatment, the more invested she will become in her own preparation and rehabilitation. This point is supported by the findings of the ENDOW Study.

The art of touching, the therapeutic laying on of the hands, is important. Being lonely, frightened, and sick is a reason for the patient to be touched by her physician, especially if she seems particularly overwhelmed by her situation. To touch the patient’s shoulder or hold her hand while talking to her is therapeutic. Even a comforting hug is appropriate if it fits the circumstances and the patient reaches out to you. Before fetal monitoring, quality of labor was evaluated by sitting at the patient’s bedside with the physician’s hand on her abdomen to feel uterine contractions. Often, the presence of the physician and a warm hand on her abdomen made the patient relax, rest, and become calmer during active labor. Cancer patients, especially, on hearing bad news need immediate human-tohuman contact to stay grounded enough to face that terrible moment. The professional boundaries of roles, time, place, space, gifts and services, chaperoned examinations, physical contact, money, and formal language were never intended to be an impermeable membrane separating a doctor’s ability to administer human kindness. A healer’s touch can often comfort a distressed patient when words are inadequate.

A patient’s family is a vital part of her support system and can be a potent ally, or not, to the health care team. If your patient requests that family members be present during her consultation, allow it, but speak directly to her whenever possible.

Once the initial presurgical discussions are complete, your patient may need some time to digest all the new information she has received. After assimilation, allow her to contact you for clarification or to ask more questions. This is especially important if the procedure involves new techniques or technologies.

Patients have the right to know the physician’s level of experience regarding surgical techniques, as well as a thorough description and performance history of any device that will be used or implanted in their bodies. Rosen believes this is especially important because different procedures have different risks, and the patient should know why her physician prefers one method or product over another. Other countries have government registries that track the outcomes and complications of

medical devices so surgeons can quickly determine superior and inferior performers. A physician expert in a Swedish hip registry disclosed, “The risk in the United States that a patient will need a replacement procedure because of a flawed product or technique can be double the risk of countries with databases… and doctors in Sweden are much less likely than American doctors to embrace new devices until registry data show they work.” The American patient should know the status of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) surveillance and whether the physician and device manufacturer have any financial connection.

medical devices so surgeons can quickly determine superior and inferior performers. A physician expert in a Swedish hip registry disclosed, “The risk in the United States that a patient will need a replacement procedure because of a flawed product or technique can be double the risk of countries with databases… and doctors in Sweden are much less likely than American doctors to embrace new devices until registry data show they work.” The American patient should know the status of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) surveillance and whether the physician and device manufacturer have any financial connection.

Patient-clinician communication has never been more important. Paget et al. list seven basic principles as a starting point:

Mutual respect

Harmonized goals

A supportive environment

Appropriate decision partners

The right information

Transparency and full disclosure

Continuous learning

Patients from Other Cultures

In the United States, the number of patients from other cultures is increasing dramatically. In many cases, these patients are situated in dense clusters, and physicians in these areas are either multilingual or have assistants who are able to act as interpreters. However, no matter where your practice is located, chances are that at some point during your career as a physician, an individual from another culture will need your help.

Mull makes the following suggestions for communicating effectively with a person whose language you do not speak and whose culture is foreign to you: Make sure that your office staff are courteous and respectful. Show the genuine concern you feel. Be friendly and helpful to build rapport and develop a repertoire of knowledge. Familiarize yourself with the general principles of their traditional medicine. Whenever possible, have an interpreter present. Learn a few key phrases in their language, and use these for initial greeting and during examinations. Electronic linguistic assistants, such as the Franklin devices, are available in most languages. Include, at least in discussion, any family members your patient considers influential. Always ask what they have done to treat themselves. Have they consulted an influential family member? A healer? Have they used home or herbal remedies?

Physicians should be aware of common themes that exist in cross-cultural medicine, including the following:

Fear of blood loss

Fear of cold

Tradition of male dominance

Conservatism in sexual matters relative to teenage girls

Poorly developed concept of preventive medicine

Intolerance of side effects from medication

Expectation of expeditious wellness

Reluctance to discuss emotions with people who are not family members

Diaz-Gilbert cautions health care professionals to check their prejudices at the door and not to assume that a non-English-speaking person is uneducated. The following are some guidelines for effective communication with patients from other cultures:

Allot extra time for the patient from another culture.

Address every patient initially in English.

Ask if the patient carries a bilingual dictionary.

Gesture or write down simple words or phrases.

Use visual cues, such as insurance forms, calendars, medication bottles, or anatomical sketches. If necessary, draw a picture to convey what you mean.

If the patient needs to perform a specific task, such as disrobing, carefully pantomime each step. Remain aware that direct eye contact, certain hand or finger gestures, and physical touch are offensive, are disrespectful, or can be construed as sexually suggestive in certain cultures.

When a cultural language barrier exists, reliance on body language becomes crucially important. Work at learning to read it. These patients experience the same emotional responses to surgery and need the same education and reassurances. Having to use the services of a foreign doctor in an alien land makes the surgical process even more frightening for them.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PREPARATION FOR SURGERY

Massler and Devansan said that there is an emotional response to any physical assault on the body. The magnitude of the response is expected to be proportional to the degree of emotional investment one has in the part of the body under siege. Among women, anatomic entities most vulnerable to this emotional reaction are the face, hair, breasts, genitalia, and abdominal wall.

Second only to cesarean birth, hysterectomy is the most frequently performed major surgical procedure done on reproductive-aged women. Over 600,000 women a year have hysterectomies in the United States. Newer, minimally invasive procedures have shortened hospital stays and have lessened visible disfigurement of the body. Schwartz and Williams of the Mayo Clinic concluded that detrimental psychological effects reported to occur after hysterectomy are not supported by prospective studies. Indeed, in most patients, mood was elevated.

The majority recover quickly from the procedure and enjoy the new freedom that comes to an individual when a chronic health problem has been resolved. Your patients, however, are not always older, wiser women, and they do not always recover quickly. If you know the signs to look for, you will be able to help that patient who is having a harder time adjusting to pelvic surgery, especially if it was a radical, life-threatening, or unexpected event.

In his book, Matters of Life and Death, Daniel Bruns writes, “Even the strongest person can be shaken by the horrors of some medical cures. Beyond this, life anxiety is even more common in persons with pre-existing emotional difficulties or characterologic disorders. These persons may go through life like eggshells, intact and functioning, but with psychological fragility. When faced with an extreme life stressor, such a person may simply shatter.” How will you, as the physician, recognize the vulnerable?

Roeske researched 13 factors related to poor prognosis for excellent mental health after hysterectomy. The following factors begin to define the patient who might react negatively to genital surgical stress:

Gender identity

Previous adverse reactions to stress

Previous depressive episodes

Family history of mental illness

History of multiple physical complaints, especially lower back pain

Numerous hospitalizations or surgeries

Age less than 35 years at time of hysterectomy

Desire for a child or more children

Fear of loss of libido

Significant other’s negative attitude toward procedure

Marital dissatisfaction or instability

Cultural or religious disapproval

Lack of vocation or hobbies

Barnes and Tinkham’s research also indicates that patients tend to react to current stress in much the same way as they reacted to past crises and personal losses. Well-established patterns of behavior repeat themselves. By taking a patient’s history, the surgeon can be forewarned about which patients are likely to have the most difficulty handling the emotional aspects of gynecologic surgery. Equipped with this information, the surgeon can prepare to offer extra support in the form of reassurance, educational information, and—if indicated or requested—the names of psychotherapists who are trained to deal with women’s health issues.

The Psychology of Pelvic Pain

Andrews said the problem of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is very common. “About one in ten outpatient gynecologist appointments, up to 40 percent of laparoscopies, and up to 12 percent of hysterectomies are for chronic pelvic pain. We spend over a billion dollars just on outpatient management of chronic pelvic pain.”

Singh, Rivlin, et al. list the following psychophysiologic therapies as possible interventions to reduce the severity of the symptoms: reassurance, counseling, relaxation therapy, stress management, and biofeedback techniques. They caution that consultation with a psychologist, urologist, neurologist, and gastrointestinal or other specialist is very important before considering invasive or aggressive management.

Management of the pain is difficult because there could be so many possible causes: Endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, adhesive disease, pelvic congestion syndrome, ovarian retention syndrome, ovarian remnant syndrome, adenomyosis, and leiomyomas, and the list goes on. Benjamin-Pratt and Howard believe the best approach may be to use a combination approach that treats the disease and also teaches pain management.

Chronic or constant pain causes immense suffering because the patient cannot escape it or never knows when it will strike. Acute pain, like that of childbirth, has a beginning and a real end. The woman knows that no matter how much she hurts, there will be relief soon. While awaiting diagnosis or surgical treatment, the patient should be encouraged to keep a pain diary.

Pelvic Pain Support Network lists helpful suggestions to describe pain. These are useful for self-illumination for the patient as well as a diagnostic aid to present to the doctor:

On a scale of 0 to 10, how bad is the pain?

How long have you been having the pain?

Where is the pain?

Has the pain ever been diagnosed? If so, what was the diagnosis?

What investigations have you had in the past?

Describe the pain in your own words (burning, stabbing).

What makes the pain worse? What makes it better?

Is there a pattern? Diaries are useful for this.

Have you been prescribed medication? Did it help or not?

What activities does the pain prevent you from doing?

How long can you do a certain thing before you have to rest?

Common Emotional Responses to Surgery

Insecurity

Giving up control of one’s body, even temporarily, is uncomfortable for all of us, but it is terrifying for people who feel generally insecure. One of the most common defense mechanisms against feelings of insecurity is to institute rigid controls over all aspects of life. These patients may have no control over getting sick. They will have little if any control during the surgical procedures. The postsurgical setting will be a hospital room where the staff tell the patient when to awake, take medicine, eat, bathe, walk, have visitors, and have blood drawn. The health care workers will probe such personal matters as urination, defecation, and passage of flatus. Anxiety, anger, and feelings of being assaulted combine with insecurity to produce an unhappy, fearful, and sometimes raging patient.

These feelings are greatly diminished when the patient believes the surgery will improve her quality of life. There will eventually be relief from pain, removal of cancer, an end to heavy bleeding, restoration of fertility, or some other positive result. She will be better than she was before the surgery. The transition to becoming this healthier person is made easier when she trusts and believes in her physician.

Anxiety or Fear

Anxiety or fear associated with surgery is essentially universal. Most common is fear of the unknown or of what the patient imagines she will be forced to endure during hospitalization. Factual information about the surgical and recovery process and competent care by a compassionate hospital staff help to diminish this fear. Surgeons should assume responsibility for the behavior of the hospital staff toward their patients. When a patient complains of ill treatment by any of the health care providers, the physician should deal with the situation personally to decrease the probability of a future recurrence of the offensive or thoughtless behavior.

Patients may fear the loss of economic competence. A woman who has worked for many years may lose her sense of usefulness when disabled for some length of time. Whether she plays a major or minor role, the contribution she makes to her family’s economic stability will be important to her. The sense of identity and self-esteem she derives from her job may also be threatened by the outcome of her surgery.

Fear of anesthesia is often a thinly disguised fear of dying as well as a fear of loss of control. It may be appropriate to confront the fear of dying directly so that the patient has the opportunity to express why she is afraid. Is the fear general or specific? Did a close relative suffer from the same affliction and die during or shortly after surgery? Does the patient have a strong intuitive feeling that something will go wrong? If so, ask her what you can do to modify the surgical situation. Determine whether the scheduled date of surgery or the particular hospital is significant. The fact that you consider her feelings an important issue and a normal part of the gynecologic disease process may be enough to calm her fears.

Regression and Dependency

In most people who are ill or who undergo surgery, regression to a more dependent state is fairly common. Dealing with a woman who is no longer self-sufficient or emotionally stable is difficult for the patient’s family and friends. These members of her supporting cast are accustomed to her presurgical roles as wage earner, wife, mother, friend, cook, adviser, shopper, housekeeper, taxi driver, entertainer, and more. When she becomes ill and can no longer function to make their lives easier, family

members and friends often become frustrated and angry. They may apply overt or subtle pressure to try to force the woman to exert herself and fulfill her usual roles. A change in roles is difficult, but often the illness teaches family and friends why this particular woman is valuable to them. In many cases, those who temporarily assume her normal duties or help her cope with the surgical experience discover strengths of hers of which they were previously unaware.

members and friends often become frustrated and angry. They may apply overt or subtle pressure to try to force the woman to exert herself and fulfill her usual roles. A change in roles is difficult, but often the illness teaches family and friends why this particular woman is valuable to them. In many cases, those who temporarily assume her normal duties or help her cope with the surgical experience discover strengths of hers of which they were previously unaware.

When the disease and prospect of surgery are new to the patient, all these factors, as well as a feeling of ill health, contribute to an emotional fragility that yields extremely labile emotions, including feelings of sadness, despondency, tearfulness, and irritability. The usual defense mechanisms are often temporarily weakened or destroyed. The woman is vulnerable to attack on all personal and professional fronts. She needs time with people she cares about, and she needs time alone to sort out her thoughts and emotions.

Grief

Grief is a normal, natural reaction to illness or loss of any kind; it is essential to emotional healing. Recognizing the various stages of grief allows the surgeon to help the female patient understand what is happening to her.

Denial is the first and most primitive emotional response to loss, and it can take many forms. The patient may demonstrate denial by not going to the doctor when she finds a lump in her breast or when she notices abnormal bleeding. She may pretend the symptoms do not exist or are a temporary nuisance. Not remembering instructions the physician gave her could be a manifestation of denial. She may forget important facts or deny the seriousness of the problem. Denial allows people to function for a little while in a make-believe world. With this primitive mechanism, they survive emotional stresses they might otherwise be unable to handle.

Bargaining with a higher power is the second stage of grief. Many patients feel they have carte blanche to bargain when they are experiencing a loss. “Make this bad thing that has happened to me go away, and I swear I will become a better person.”

Guilt can surface before or after a loss. Most guilt feelings are completely inappropriate, in that the focus of the guilt rarely is directly related to the cause of the loss. When they are sick, many people feel that they are being punished for not being perfect. Explain to your guilt-ridden patients that their feelings are normal under the circumstances. Although guilt can sometimes deliver devastating, incapacitating blows, the good news is that it is usually transitory.

Depression comes in varying degrees to most people experiencing grief; it is characterized by feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and worthlessness. Other symptoms include middle-of-the-night insomnia, nightmares, loss of appetite or excessive eating, lethargy, difficulty making decisions, psychosomatic symptoms, and fatigue unexplained by activity.

Ask the patient if she has any of these symptoms. Postsurgical depression is common. Depressed patients usually admit that the sad feelings are routine and occur daily. When prolonged, they indicate the patient has been unable to work through the grief process. Something emotional has yet to be resolved.

Rage turned inward often manifests as depression. When the patient is able to identify what she is angry about, to ventilate the rage, the depression usually begins to lift. When she takes charge of her life again and makes decisions, even small ones, she begins to feel better, and feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and worthlessness abate. However, when the depressed patient becomes suicidal, stringent intervention must occur. The suicidal patient presents serious challenges and will be discussed in specific detail later in this chapter.

The stage at which the patient ventilates her anger can be difficult for those providing care, but it should be accepted as healthy. The patient may go to extremes, writing letters to the newspaper or speaking of suing her physician. She may complain bitterly about the nursing staff and the hospital. Such actions are a form of protest at the stress that has been dealt to her body and mind. In most instances, this behavior means that the depression is lifting and the patient is beginning to move toward the resolution of her grief. The depressed patient should be encouraged to ventilate by talking, to establish an enjoyable form of physical exercise, and to begin to take charge of her own life.

Resolution and integration eventually occur. The stressful experience of loss finally becomes an accepted part of her life. The memory causes sadness and regret, but no longer the devastating immobilization found in the earlier stages of grief. Integration does not mean the experience is forgotten, only that it has less trauma associated with it. After integration, certain stimuli can provoke flashback grief. The painful emotional tapes begin to play again, but the patient learns that the bad time is a rerun and will not last long.

The stages of grief do not always occur in order. The patient may feel fragments of several of them at the same time. If a female patient’s behavior seems bizarre, excessive, or out of the realm of what would usually be anticipated during her particular surgical experience, look for the role grief might be playing in her life.

PSYCHODYNAMICS SPECIFIC TO DIAGNOSIS AND SURGERY

Patient-Physician Bonding

Neither scalpel nor laser can divide the psyche from the soma. As technical skills have improved and multiplied, robotic surgery has become commonplace, and comprehensive care of the gynecologic patient has declined. However, a knowledgeable and compassionate PA (physician’s assistant) can be invaluable to both the surgeon and the patient. Increased emphasis on scientific and procedural care usually means less time in the consultation room and more time in the examining or procedure rooms. This is unfortunate for all concerned, because it takes time to explore the concepts, fears, and psychological wellbeing of the individual patient both before and after surgery.

It takes time to scan the books and magazines women read, to search the same Internet sites, to listen to the voices of their advocates, and to evaluate, critique, and learn from their sources of information; but it is important to make the effort. Otherwise, you run the risk of being out of touch, or worse still, appearing arrogant and condescending. Women in general have a sixth sense about these attitudes, and women about to undergo surgery or those recovering from surgical trauma to their bodies are hypersensitive to all manner of psychological stimuli.

The medicolegal climate has also potentiated perioperative anxiety. When you inform your patient, as she prepares for surgery, that she can bleed to death, be subjected to blood transfusions, have an adverse reaction to anesthesia, or sustain bowel or urinary tract injuries, you augment her innate fear of surgery. Some patients experience strong pressure from extreme feminist groups to seek and maintain a controlling role in her life, over her destiny, and over the surgeon. Under these circumstances, it is more necessary than ever for the pelvic surgeon to take the time to explore the patient’s psyche in

the preoperative and postoperative periods in order to avoid undesirable psychological sequelae. Having personable, competent health care workers in your office who assist in preparing your patient for surgery is also indispensable. Anatomical charts have become works of art, and they, as well as videos and other teaching aids, are useful in explaining the technical details; however, despite all the educational tools and staff assistance, the most important person remains you, the doctor. Unless you sit and answer questions on a one-to-one basis, you are neglecting your responsibility to her.

the preoperative and postoperative periods in order to avoid undesirable psychological sequelae. Having personable, competent health care workers in your office who assist in preparing your patient for surgery is also indispensable. Anatomical charts have become works of art, and they, as well as videos and other teaching aids, are useful in explaining the technical details; however, despite all the educational tools and staff assistance, the most important person remains you, the doctor. Unless you sit and answer questions on a one-to-one basis, you are neglecting your responsibility to her.

Much of the time, the questions will deal with information the patient has gleaned from literature, popular talk shows, and the Internet. Some of the opinions she reads or hears will frighten her or make her suspicious, and a few patients may initially come to your office thinking of you as a potential enemy. A staunch feminist may express the belief that you are just another insistently prosurgical doctor out to highjack her womb and add it to your trophy collection.

Popular literature today often stresses sexism, ageism, and greed on the part of doctors. The Silent Passage and Our Bodies, Ourselves were among the first widely read books on which patients depended for their gynecologic information. In these, they read that “for well over a century in the United States, women’s uteri and ovaries have been subject to routine medical abuse,” and “one should not be railroaded into hysterectomy nor onto hormones.” Hysterectomy is described as “devastating” surgery, and for some women, it certainly can be. These books found a wide audience and led to the publication of other books, which took an even more radical approach, all in the name of protecting women from castrating medical experts who might use their position of authority to hurt, not help, them.

The Ultimate Rape: What Every Woman Should Know About Hysterectomies and Ovarian Removal was inspired after the author underwent a hysterectomy. She suffered extreme physical and emotional trauma following the surgery, but when she complained to her physicians, they advised her to go see a psychiatrist, because all her symptoms were in her head. The book’s title is evidence of the rage she felt at their pronouncement. Now her voice is joined by others who believe every woman has the right to be thoroughly informed about procedures and consequences before consenting to gynecologic modifications. And certainly, a woman should.

In No More Hysterectomies, touted as the first living textbook on the Web, the reader learns how the male-dominated medical profession and the insurance industry have sanctioned millions of unwarranted hysterectomies. One testimonial to the ideas presented in the book describes the current medical environment as a “woman’s hormonal holocaust.”

The enlightening news is that interest generated by these sources and their legions of followers has had a positive and direct effect on women’s health research. Global studies are numerous and are concentrating on traditional as well as alternative methods of treatment for menopause, hysterectomy, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), cancer, endometriosis, fibroids, and dementia. For the first time in the history of medical science, research is being conducted on a large scale to determine how women of various ethnicities and cultures and with differences in their physiology react to menopause, gynecologic surgery, hormone therapy, and sexual function. The ENDOW Study has found ethnic/racial differences in women’s perceptions of hysterectomy and their decision making regarding elective surgery. Negative connotations were found to be more prevalent among African-American women, thus indicating a need for added support and preoperative information. Future generations of women will reap the benefits from this research, but the overwhelming aura that prevails in today’s gynecologic patient is one of confusion.

After reading just a sampling of the lay literature, some women feel that surgical removal of their female organs and commencement of hormonal therapy constitutes an unnatural, chemotherapy-like assault on their physical bodies. It is the task of the physician to admit into evidence the medical facts necessary to correct any gross misconceptions that could affect patient care. Sometimes, it may seem as if the patient, armed with advice about natural remedies for her severe pelvic pain, heavy bleeding, or hot flashes, wants to drag you with her back into the Dark Ages. Be patient and also prepared, if necessary, to explain the medically sound benefits of life lived outside the cave.

Be compassionate. No matter how routine the job becomes, compassion is a vital requisite to becoming an exceptional communicator and healer. Empathy often follows experience, and those times when you are able to make a noticeably positive difference in your patient’s life are inspirational. To try the one new thing that might help many patients in the future, it is necessary to earn the trust of a single patient in the present.

The days are gone when a doctor was considered omnipotent, when he—and rarely, she—received a hock of ham for the birth of a child or had to tell a woman that she would have to live with the eventual hump on her back because it was a natural process of aging. Patients know about osteoporosis and heart disease and about reproductive technology and brain neurotransmitters. The media have turned every living room into a medical school. Some patients present videos and clippings detailing current research and experimental treatments relative to their specific diagnoses. They know a little, and they want to know more. Many patients want to participate in their health care and absolutely should be encouraged to do so. Unlike the doctors of old, who, for the most part, had to contend with an uneducated populace, the modern physician must form a partnership with the modern patient. Mutual responsibility, respect, and trust eventually strengthen this bond.

The cornerstone of the initial work is truth. Use good judgment about when to tell all the facts, particularly those that point to a devastating diagnosis, but never lie. In 1961, 90% of physicians surveyed in a single, large urban hospital stated that they withheld the diagnosis of cancer from their patients. Today, the position has been totally reversed, with 97% reporting that they reveal the true diagnosis of cancer.

Doctors, however, are not the only members of the team with ethical obligations. Patients also have the responsibility to tell the physician the truth relative to their symptoms, medications, allergies, and past medical histories and to relate any significant traumas or family history that could affect their current situations.

Question your patient specifically about stressful life events. Did she respond to these in a positive or negative way? Of all inquiries, this is the most important indicator of how the patient will respond to any current stress. Once the physician knows the answer, psychological preparation for diagnosis or surgery can begin in earnest.

Researchers in the United Kingdom have compiled data from multiple trial studies confirming that psychological preparation for surgery is effective. The general hypothesis was that communication and counseling are important determinants of numerous factors, including the following:

Accuracy of the diagnosis

Effectiveness of disease management

Disease or problem prevention

Patient satisfaction

Adherence to treatment

Psychological well-being

Patient understanding of procedures

Professional satisfaction and levels of stress

Information about each of these parameters was compiled, and considerable evidence existed to support all the hypotheses. In review, Davis and Johnston reported that psychological preparation is effective in reducing negative effect, pain, medication, and length of hospital stay and in improving behavioral recovery and physiologic functioning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree