Psychologic Disorders of Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

Michael W. O’Hara

Lisa S. Segre

Depressive and anxiety disorders are common during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These disorders may impair the woman’s self-care during pregnancy and negatively affect her parenting after delivery. The patterns of presentation vary widely. Depressive and anxiety disorders may exist before the pregnancy, or they may develop during pregnancy or after delivery. Sometimes, they are quite apparent to the obstetrician examining an obviously sad or anxious woman. Often, they are not obvious because women may conceal emotional disturbance for reasons that include stigma, fear of the baby being taken away, not recognizing that she has a psychiatric disorder, or simply not wanting to bother the doctor. Women with severe mental illness who become pregnant usually are already under the care of a psychiatrist. However, some women develop a “postpartum psychosis” within a few weeks of delivery. Although a previous history of psychosis is the most significant risk factor, the majority of women experiencing a psychotic episode after delivery have no significant history of psychiatric illness. Thus, the tasks of the obstetrician with respect to these disorders are to (a) understand their nature, risk factors, and consequences for the mother and fetus or child; (b) detect and assess for them during clinical visits; (c) educate patients and families; and (d) make effective referrals and/or manage clinical care of these disorders.

In the first part of this chapter, perinatal psychiatric disorders are described, including their clinical presentation, prevalence, effects, and management in an obstetric setting. Because the detection of these disorders is not reliably accomplished by direct observation alone, the second part of this chapter will describe patient education and screening approaches feasible for an obstetrics office setting.

Postpartum Blues

Description

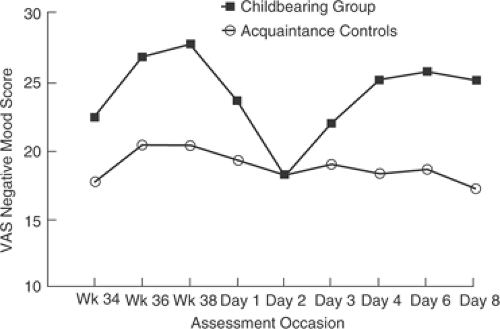

In the early postpartum period, many women experience a mild mood disturbance referred to as “postpartum blues.” Symptoms often are most noticeable between days 3 and 5 postpartum and typically last anywhere from several hours to several days. Figure 28.1 illustrates this pattern. It shows daily mood ratings of a sample of pregnant and postpartum women at several time points in late pregnancy and the early postpartum period. By day 2 after delivery, women experience negative mood at about the same level as comparable women who have not recently delivered a child. Negative mood increases, peaking at day 6 postpartum. It is interesting to note that mood is, on average, more negative late in pregnancy than at the time in the postpartum period during which the blues peaks in intensity. Finally, although the term blues primarily connotes sadness, it is not a form of mild depression. It might best be considered a problem in affect regulation. Prominent symptoms include mood lability, irritability, interpersonal hypersensitivity, insomnia, anxiety, tearfulness, and even elation.

Because the blues is common and almost always occurs in close proximity to childbirth, the phenomenon is considered normal and probably hormonally driven, though

research is inconclusive in this respect. The literature does suggest that women with a history of depression are at increased risk for the blues and that the blues is itself a risk factor for later depression. These and other findings suggest that the blues may lie within the spectrum of affective disorders.

research is inconclusive in this respect. The literature does suggest that women with a history of depression are at increased risk for the blues and that the blues is itself a risk factor for later depression. These and other findings suggest that the blues may lie within the spectrum of affective disorders.

Prevalence and Effects

Because there is no single accepted definition of the blues, estimates of its prevalence have varied considerably, ranging from 26% to 84%. Table 28.1 includes two definitions of the blues, the Pitt and the Handley criteria. The Pitt criteria will identify about half of postpartum women as experiencing the blues, while the Handley criteria will identify about a quarter of women as experiencing the blues. Generally, the blues lasts no more than a few days, requires no treatment, and is not associated with negative sequelae. However, in some cases, what appears to be the postpartum blues is actually the beginning of a depressive episode, which is discussed in the section on Perinatal Depression.

TABLE 28.1 Definitions of Blues Based on Pitt and Handley Criteria | |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Management

Prenatal education about the frequency, normality, and the symptoms of this mild mood disturbance will help new mothers and their families keep the blues in proper perspective (i.e., recognize that the blues is a common phenomenon, that it passes quickly, and that there are no consequences). It is especially important to provide this type of normalizing information to women who experience the blues to relieve any guilt feelings or fears they may have because they are unexpectedly experiencing negative feelings about the new baby. This education can occur in childbirth preparation classes, by nurses or physicians during prenatal visits, and on the maternity ward. Patients should be instructed that if their “blues” continues beyond a week’s period and they do not seem to be feeling better by the end of the second week postpartum, they should contact their obstetrician or primary care physician. The patient actually may be in the early stages of a major depression, which requires prompt treatment.

Perinatal Depression

Depression may preexist the pregnancy or begin at any time during pregnancy or the postpartum period. It is a devastating disorder that robs women of their joy and energy and creates impairment in self-care and parenting. There often is confusion surrounding this term. Major depression that occurs in the postpartum period usually is referred to as “postpartum depression.” The term postpartum depression does not exist in the diagnostic nomenclature and, in fact, often is erroneously used to refer to cases of the postpartum blues and postpartum psychosis as well as any other mood disturbance (including anxiety) that are prevalent in the postpartum period. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV-TR) includes “postpartum onset” as a “course specifier” if the episode of major depression begins in the first 4 weeks after delivery. In clinical practice, however, the diagnosis is applied to a major depressive episode within the first year of childbirth.

The adjective postpartum before depression also is misleading, implying that there is something about childbirth or the early postpartum period that causes or contributes to the onset of a depressive episode. Although this may be true for postpartum psychosis (see later discussion), the empirical evidence linking childbirth per se to the onset

of depression is at best equivocal. Several studies (admittedly with relatively small sample sizes) comparing rates of depression in postpartum and nonpostpartum women have found little evidence of elevated rates of depression associated with childbirth. Nevertheless, depression is common in the postpartum period (and pregnancy) and should be treated. Epidemiologic research confirms that the period of highest risk for depression among women is in the age range of 18 to 45 years, the years during which most women will bear children. These data also suggest that the obstetrician–gynecologist should be alert to depression even in the context of yearly exams.

of depression is at best equivocal. Several studies (admittedly with relatively small sample sizes) comparing rates of depression in postpartum and nonpostpartum women have found little evidence of elevated rates of depression associated with childbirth. Nevertheless, depression is common in the postpartum period (and pregnancy) and should be treated. Epidemiologic research confirms that the period of highest risk for depression among women is in the age range of 18 to 45 years, the years during which most women will bear children. These data also suggest that the obstetrician–gynecologist should be alert to depression even in the context of yearly exams.

Description

The diagnosis of major depression requires the presence of either sad mood or the loss of interest and pleasure in usual activities along with four additional symptoms (Table 28.2). These symptoms must be present for more days than not over a 2-week period, must represent a change from previous functioning, and must cause significant distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning. Minor depression refers to an episode of at least 2-weeks duration in which there are two or more but less than five symptoms, (including sad mood or loss of interest). Other requirements are the same as for major depression except that the requirement for impairment in functioning is somewhat less than that for major depression.

Prevalence

Estimates based on recent meta-analyses suggest that 18.4% of women will experience a major or minor depression at some point during pregnancy, and for major depression it is 12.7%. The period prevalence for major and minor depression during the first 3 months postpartum is 19.2%, and for major depression it is 7.1%. The rates for incident episodes in pregnancy and the postpartum period are similar, 14.5% and 6.5%, respectively. Rates of depression are higher in populations that have significant risk factors, such as women with history of depression or women living in poverty.

TABLE 28.2 Criteria for Major Depressive Episode | |

|---|---|

|

Effects

Depressed women relative to nondepressed women during pregnancy use more alcohol, tobacco, and drugs of abuse, and they have poorer nutrition. Depressed pregnant women also are more likely to experience nausea and vomiting, prolonged sick leave during pregnancy, and increased visits to the obstetrician. There is evidence that depressed and anxious women have higher rates of operative deliveries and are at increased risk for preterm delivery and low birth weight. Finally, infants of depressed mothers are more likely to be admitted to a neonatal care unit and have lower scores on neurologic development scales.

After the infant’s birth, depressed mothers are less likely to engage in positive maternal safety practices such as using electrical outlet coverings or placing the child in a car seat. Depressed mothers interact with their infants in ways that are less sensitive, more negative, and less stimulating than nondepressed mothers. These suboptimal parental practices have a negative effect on child development—toddlers of depressed mothers have poorer social and emotional development as demonstrated by increased likelihood of insecure attachments, unfavorable self-concepts, and delays in intellectual development. Maternal depression also is associated with increased risk of child abuse. Because women may experience depression chronically, these deleterious consequences for children persist over time and include internalizing and externalizing behavior problems as well as depression during adolescence and young adulthood.

Risk Factors

Depression and its risk factors can be best understood within a biopsychosocial framework. Some women inherit a susceptibility to depression that is manifest in emotion or affect regulation. Indicators of a basic vulnerability to depression include a personal and family history of depression and related disorders. Other risk factors are more social in nature (Table 28.3). Determination of the presence of these factors early in pregnancy will alert the clinician to the need to develop plans to follow “at-risk” patients more carefully than normally would be the case (i.e., using key interview questions or using simple screening tools). Although there is no simple algorithm linking the number of risk factors to likelihood of depression, it is the case that the greater the number of risk factors (particularly those

reflecting biologic vulnerability), the greater the likelihood that an episode of depression will develop.

reflecting biologic vulnerability), the greater the likelihood that an episode of depression will develop.

TABLE 28.3 Risk Factors for Perinatal Depression | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Special Populations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree