Prevention and Management of Meconium Aspiration

Jordan D. Lipton

Introduction

Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid is thought to indicate fetal distress and is seen predominantly in infants who are postmature or small for their gestational age. It rarely occurs in newborns of less than 38 weeks gestation. Meconium is present in the amniotic fluid in 10% to 15% of deliveries (1,2,3) and is best managed quickly and aggressively when there is evidence of fetal distress or neonatal depression during a delivery room or emergency department (ED) delivery. Meconium aspiration syndrome is defined as the presence of meconium below the vocal cords associated with some degree of respiratory distress and hypoxia. With appropriate management, only 5% of neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid develop the syndrome (4). Unfortunately, for those infants who do develop the syndrome, meconium can be responsible for severe pulmonary complications (5).

Anatomy and Physiology

Meconium first appears in the fetal ileum between the 10th and 16th week of gestation. It is a viscous liquid composed of gastrointestinal secretions, cellular debris, bile, pancreatic secretions, mucus, blood, hair, and vernix. Passage of meconium before birth may be a normal physiologic event, and the maturation of peristaltic activity may account for the increased incidence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid seen with increased gestation. An increase in the passage of meconium is also associated with fetal asphyxia.

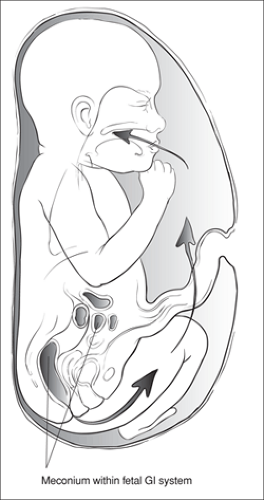

Respiratory movements are normal in utero. The general direction of amniotic flow is from the lungs and kidneys to the amniotic sac. Asphyxia of the fetus stimulates deep breaths and gasping, which results in aspiration of amniotic contents into the lungs (Fig. 37.1). As a result, meconium aspiration may occur both in utero and at the time of delivery and may indicate fetal distress or asphyxia.

Meconium aspiration syndrome is associated with a wide range of respiratory symptoms, from mild to severe. Meconium has been shown to produce mechanical obstruction, chemical pneumonitis, pulmonary vessel vasoconstriction, surfactant inactivation, and complement activation. In severe cases, meconium aspiration results in pulmonary hypertension and persistent fetal circulation with right-to-left shunting. Air leak also has been noted as a complication of significant meconium aspiration (1,5).

Indications

Meconium is a dark brownish-green material. The distinction between thin and thick refers to its density, which varies from liquid to semisolid. This consistency is dictated by the quantity of meconium that is passed and the amount of amniotic fluid in which it is diluted. With increasing gestational age, the relative amount of amniotic fluid decreases, resulting in thicker meconium. Fetal stress also may be responsible for increased passage of meconium and therefore a thicker consistency.

Two approaches have been advocated to prevent meconium aspiration. The first alternative—selective intubation—involves visualizing the glottis using a laryngoscope, followed by intubation and suctioning of the infant, but only if the infant is depressed. This approach is taken by authorities who

believe that when signs of distress are absent, an infant is unlikely to have a significant amount of meconium in the trachea. The second option—universal intubation—involves endotracheal intubation and suctioning whenever thick meconium is present in the amniotic fluid. The latter approach has fallen out of favor since it has been found that tracheal suctioning of the vigorous infant with meconium-stained fluid does not improve outcome and may cause iatrogenic complications (6,7). This is in spite of the fact that one study found 9% of meconium-stained infants had meconium suctioned from their tracheas when no meconium was visible in the mouth, in the pharynx, or at the vocal cords (3).

believe that when signs of distress are absent, an infant is unlikely to have a significant amount of meconium in the trachea. The second option—universal intubation—involves endotracheal intubation and suctioning whenever thick meconium is present in the amniotic fluid. The latter approach has fallen out of favor since it has been found that tracheal suctioning of the vigorous infant with meconium-stained fluid does not improve outcome and may cause iatrogenic complications (6,7). This is in spite of the fact that one study found 9% of meconium-stained infants had meconium suctioned from their tracheas when no meconium was visible in the mouth, in the pharynx, or at the vocal cords (3).

Thus, vigorous infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid (whether thick or thin) rarely require special intervention. However, meconium-stained amniotic fluid in association with a depressed neonate requires endotracheal suctioning. It is estimated that 95% of cases of meconium aspiration syndrome develop in the presence of thick meconium (2). A vigorous infant with a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute, effective spontaneous respirations, and good muscle tone within the first several seconds after birth will likely not benefit from immediate tracheal suctioning, but continued assessment is mandatory (7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree