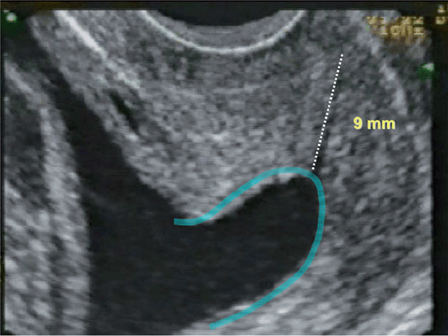

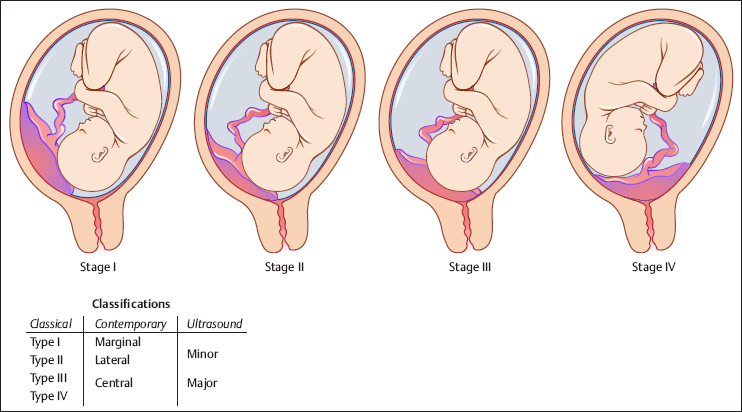

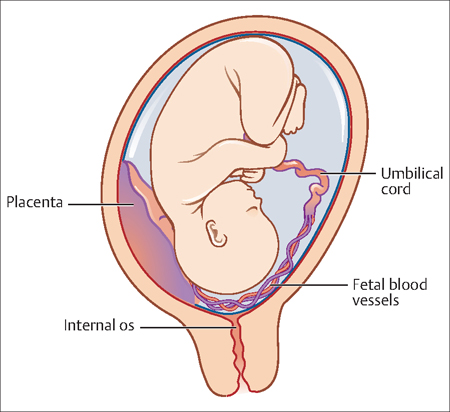

20 Premature Rupture of Membranes and Third Trimester Bleeding E. Albert Reece Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and third trimester bleeding represent two of the most serious complications of pregnancy. Preterm PROM is responsible for approximately one-third of preterm deliveries. Similarly, few obstetric emergencies cause greater concern than bleeding in late pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period. Third trimester bleeding is a major cause of maternal and fetal mortality. Massive bleeding can occur without forewarning, and there are few reliable clinical indicators available to predict those at greatest risk. Patients may remain hemodynamically stable until a sudden deterioration in condition takes place. In many cases the extent of the bleeding can be unclear, as the bleeding may be concealed behind the placenta. Placental abruption (abruptio placentae): This term is used to describe a partial or complete separation of the placenta from the wall of the uterus. Placenta previa: Placenta previa is a placental implantation that overlies or is within 2 cm (0.8 in) of the internal cervical os. A complete previa is placenta that covers the os. A marginal previa occurs when the edge lies within 2 cm of the os. When the edge is 2–3.5 cm (1.4 in) from the os, the placenta may be described as low lying. Premature rupture of membranes (PROM): This is a membrane rupture that occurs before the onset of labor. Uterine rupture: This term describes anything in a continuum of events that can occur to the uterus during pregnancy, from a weak spot in the uterine wall noticed by the surgeon at the time of cesarean to the catastrophe of the uterus tearing open and the fetus, placenta, and a lot of blood extruding into the mother’s abdomen. Vasa previa: A condition that occurs when the fetal blood vessels are situated across the entrance to the birth canal and rupture when the cervix begins to dilate at the start of birth or during labor. The diagnosis of PROM is generally based on a suspicious history, combined with physical examination and, when indicated, additional laboratory tests. If there is a suspicious history (see below), the first confirmatory steps include performing a sterile speculum examination, visually evaluating cervical dilatation and effacement, and obtaining appropriate cervical cultures for infectious diseases, such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea. In most cases, PROM can be confirmed by documentation of fluid passing from the cervical os with visualization of a pool of fluid in the posterior vaginal fornix. Although helpful, nitrazine and ferning tests are not always accurate. A false-positive nitrazine test may occur if there is blood, semen, alkaline antiseptics, or bacterial vaginosis present in the vagina. Alternatively, if membrane rupture is chronic and little amniotic fluid is present, the nitrazine test can be falsely negative. Causes of false-positive and false-negative ferning tests include cervical mucus and prolonged leakage. Alternate adjunctive tests include vaginal prolactin, a-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and fetal fibronectin. If negative, these tests may be helpful. However, a positive test is not specific to the diagnosis of membrane rupture. Digital examination should be avoided unless delivery is anticipated, because of the increased risk of infection and the scant additional information about the mother’s condition obtained with this procedure. As previously mentioned, cervical weakness is one primary causes of PROM. Although pregnant women are routinely monitored for weakness in the lower half of the cervix, most practitioners do not routinely screen for changes in the upper half of the cervix, which can also dilate and shorten, giving it a funnel-like appearance (Fig. 20.1). This cervical “funneling” is the result of the internal portion of the cervix closest to the baby beginning to open. A funneling cervix can allow the bag of waters to slip down into the cervix and rub against it, which could cause PROM. Bleeding during pregnancy is a common occurrence. Cervical dilation during normal labor is commonly accompanied by a small amount of blood or blood-tinged mucus (bloody show), and many pregnant women experience spotting or minor bleeding after sexual intercourse or a digital vaginal examination. Minor versus serious causes of vaginal bleeding can usually be differentiated by the history, a physical examination, ultrasonography for placental location, and a brief period of observation. The use of transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of placenta previa is accurate as well as safe. In the past, the placental location was ascertained by clinical examination and digital palpation of the placental edge from the internal cervical os. However, currently the diagnosis is based on the findings of the ultrasound examination. It is well established that the use of transvaginal ultrasonography is superior to transabdominal ultrasonography in defining the relationship of the placental edge and the internal cervical os. Cervicitis, cervical ectropion, cervical polyps, and cervical cancer are possible underlying causes (see Pathophysiology below). Evaluation with a sterile speculum may be performed safely before ultrasonographic evaluation of placental location; however, digital examination should not be performed unless ultrasonography excludes a placenta previa. Fig. 20.1 Ultrasound image of a short cervix (9 mm) with funneling PROM complicates approximately 3–5% of pregnancies. The higher rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with PROM are related both independently and by increased rates of preterm birth. Prospective research has shown that there are higher rates of severe neonatal morbidity in pregnancies complicated by PROM than in those caused by idiopathic preterm labor (27% vs.15.1%, P = 0.02). It has also been demonstrated that PROM affects from 32% to 40% of preterm deliveries, with 60% to 80% of these patients entering spontaneous labor within 48 hours, with the ensuing neonatal sequelae of preterm delivery. Third trimester bleeding occurs in approximately 4% of patients. Approximately 50% of these will have an inconsequential cause and 50% will have a life-threatening event. Placental abruption occurs in approximately 1 in 120 births and accounts for 15% of perinatal mortality. Placenta previa occurs in about 1 in 200 live births. However, it rarely causes maternal hemorrhage, unless instrumentation or digital exam is performed. Spontaneous uterine rupture occurs in 0.03% to 0.08% of all delivering women, but is much more prevalent in patients with a history of uterine scarring (0.3–1.7%). Recently, it has become clear that PROM is not merely the result of the stretch and shear forces of uterine contractions, although they are contributors to the process. Rather, a “programmed” weakening of the placenta appears to be a more significant contributor to the process. Research in rats has demonstrated that collagen remodeling, with activation of matrix metalloproteinases, and apoptosis (programmed cell death) increase markedly in the amnion of a woman with PROM, suggesting the involvement of these pathways in fetal membrane weakening. The management of PROM is challenging, because once the membranes have broken, the risk of fetal or maternal infection, or both, increases. Preterm PROM adds to this management challenge, mainly because of the added problem of prematurity. PROM can also result from: infections in the ascending genital tract, which initiate a cytokine cascade that enhances membrane apoptosis; protease production and dissolution of the extracellular matrix; placental abruption with decidual thrombin expression triggering thrombin—thrombin receptor interactions and increasing choriodecidual protease production; and membrane stretch that may increase amniochorionic cytokine and protease release. Known clinical risk factors for preterm PROM include low socioeconomic status, low body mass index, prior preterm birth, cigarette smoking, urinary tract infection, sexually transmitted disease, cervical conization or cerclage, uterine overdistention, amniocentesis in the current pregnancy, and prior preterm labor or symptomatic contractions in the current pregnancy. In many cases, the ultimate cause of membrane rupture cannot be determined, however. Various other mechanisms have been proposed as causes of PROM, including mechanical, infectious, and inflammatory processes. It is apparent that a no single pathophysiological mechanism is responsible for all cases of PROM, but rather a combination of processes is in operation. Vaginal bleeding during any given time during pregnancy is not normal and is always of concern. Third trimester bleeding is often the result of the four potentially serious conditions: 1) placental abruption, 2) placenta previa, 3) vasa previa, or 4) uterine rupture. Though the exact etiology of the bleeding often cannot be determined, the onset of bleeding may provide clues to indicate the etiology. Due to the variable mechanisms for bleeding, the amount of blood loss will vary anywhere from spotting to extensive hemorrhaging requiring aggressive emergency measures. Placental abruption can be caused by trauma, hypertension, and coagulopathies. Any of these conditions can lead to the avulsion of the anchoring villi of the placenta from the expanding lower uterine segment. This leads to bleeding into the decidua basalis and can push the placenta away from the uterus and cause further bleeding. Placental abruptions are classifed by grade (0 to 3) according to severity: To date, research has identified no specific cause of placenta previa. However, it is believed that it may be related to abnormal vascularization of the endometrium caused by scarring or atrophy from previous trauma, surgery, or infection. Risk factors for placenta previa include prior placenta previa, prior cesarean delivery, increased maternal age, large placentas (e.g., multiple gestations or erythroblastosis), and a maternal history of smoking. In the last trimester of pregnancy the isthmus of the uterus unfolds and forms the lower segment. In a normal pregnancy the placenta does not overlie it, so there is no bleeding. If the placenta does overlie the lower segment, it may shear of and a small section may bleed. Placenta previa is itself a risk factor of placenta accreta, another type of bleeding disorder. Placenta previa is classifed in four stages (Fig. 20.2) according to the placement of the placenta as follows. Vasa previa is caused by the fetus’ blood vessels traversing the fetal membranes over the internal cervical os (Fig. 20.3). These vessels may originate from either a velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord or may be joining an accessory (succenturiate) placental lobe to the main disk of the placenta. If these fetal vessels rupture during delivery, fetal exsanguination can occur extremely rapidly, causing fetal death. Fig. 20.2 Illustrations of the four stages of severity of placenta previa

Definitions

Diagnosis

Premature Rupture of Membranes

Late Pregnancy Bleeding

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Premature Rupture of Membranes

Third Trimester Bleeding

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Premature Rupture of Membranes

Third Trimester Bleeding

Placental Abruption

Placenta Previa

Vasa Previa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree