Precocious Puberty

M. Joan Mansfield

A thorough understanding of the normal progression of puberty is essential in the evaluation of precocious puberty, premature thelarche, and premature adrenarche. In normal adolescence, estrogen is responsible for breast development; for maturation of the external genitalia, vagina, and uterus; and for the initiation of menses. An increase in adrenal androgens is associated with the appearance of pubic and axillary hair. Excess androgens of either ovarian or adrenal origin may cause acne, hirsutism, voice deepening, increased muscle mass, and clitoromegaly. Precocious puberty may be caused by central, gonadotropin-dependent puberty or peripheral, gonadotropin-independent precocity. Incomplete forms of puberty include premature thelarche, premature pubarche (adrenarche), and isolated premature menarche without other signs of puberty.

Premature thelarche is defined as the appearance of breast development in the absence of other signs of puberty, growth spurt, or acceleration of skeletal maturation. Premature pubarche is the appearance of pubic or axillary hair without signs of estrogenization and is usually associated with increased secretion of adrenal androgens (adrenarche). Although generally self-limited, isolated breast budding or pubic hair development may be the first sign of a true precocious puberty. Isolated premature menarche without breast development may represent precocious puberty or a benign ovarian cyst, but local vaginal lesions as a source of bleeding (trauma, infection, tumor) should be ruled out (see Chapter 21).

The workup of precocious puberty requires fairly sophisticated endocrine studies and management. Thus, referral to a pediatric endocrinologist is advisable. However, the primary care clinician can initiate the investigation and diagnosis.

Central Precocious Puberty

Over the past century, the age of onset of pubertal development and menarche has declined in the United States and western Europe, perhaps in part because of improved nutrition (1,2,3). Controversy exists as to the definition of precocious puberty in North American girls. Traditionally, breast or pubic hair development in girls younger than 8 years of age has been defined as precocious, and this is still the definition used by most endocrinologists. However, in a 1997 study of 17,000 girls aged 3 to 12 years in the United States, Herman-Giddens and colleagues reported that a group of pediatric practitioners found breast or pubic hair development to be present at age 7 to 8 years in 6.7% of white and 27.2% of African American girls seen in office practices (4). Mean age of breast development was just younger than age 10 in white girls and younger than age 9 in African Americans. Average age of menarche was age 12.8 in whites and 12.1 in African Americans, not different from previous studies. This was the first study to assess puberty in large numbers of girls younger than age 8. Most earlier studies began at age 9. Thus, it is not clear if the percentage of girls with puberty younger than age 8 has actually increased in the United States (see also Chapter 6 for discussion of early pubertal development). Obesity in children in the United States is increasing, and Herman-Giddens and associates did note an association between obesity and early signs of puberty in their subjects (4). In response to this study, a Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society task force modified the definition of precocious puberty to be the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics younger than age 7 in white or younger than age 6 in African American girls (5,6). A number of reports have since pointed out that evaluating only those girls with precocious puberty according to this new definition would miss some children who have significant pathology such as central nervous system or hormone-secreting tumors presenting only as puberty between the ages of 6 and 8 years (7,8,9). Girls who have progression to Tanner stage 3 breast development younger than age 8, girls who have both pubic hair and breast development younger than age 8, girls who are short with puberty younger than age 8, those with bone age advancement more than 2 years, and those with any neurologic issues suggesting a central process need further assessment. Although the large majority of girls presenting with breast or pubic hair development have idiopathic precocious puberty or its benign variants, premature adrenarche or premature thelarche, some girls do have specific lesions causing their precocity. Specific causes of precocity (Table 7-1), such as tumors, are more common in girls with puberty younger than the age of 6 years but may occur in girls ages 6 to 8 as well.

In true central precocious puberty, the stimulus for development is gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secreted in pulses by the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland responds to the GnRH pulsations with the production and release of pituitary gonadotropin (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH] and luteinizing hormone [LH]) pulses, which in turn stimulate the ovarian follicles to produce estrogen. In response to estrogen, the young girl has a growth spurt, develops breasts, and may begin menstruation. With the establishment of positive estrogen feedback resulting in the cyclic mid cycle LH peak, the child may ovulate and thus becomes potentially fertile. Thus, in central precocious puberty, the hormonal process is that of an entirely normal puberty occurring at an early age (10,11,12,13).

Precocious puberty is much more common in girls than boys, with a ratio of about 23:1 (14). Although the large majority of cases of central precocious puberty in girls are idiopathic, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the central nervous system (CNS) have identified CNS abnormalities, such as hypothalamic hamartomas, in some children with sexual precocity. Hamartomas most commonly present with central precocity younger than age 3, sometimes with gelastic (laughing) seizures (15,16,17,18). Although more common in younger children, CNS abnormalities causing precocity may occur at any time during childhood (19). Some authors have therefore recommended that all girls with progressive central precocity younger than age 8 have CNS imaging (12).

In gonadotropin-independent (peripheral) precocious puberty, an ovarian tumor or cyst or rarely an adrenal adenoma produces estrogen autonomously. These lesions often produce high levels of estrogens, and puberty may progress more rapidly than in a child with central precocity. Girls who are exposed to topical or ingested estrogens or androgens can also show signs of precocity such as breast development or, in the case of androgens, virilization.

In gonadotropin-independent (peripheral) precocious puberty, an ovarian tumor or cyst or rarely an adrenal adenoma produces estrogen autonomously. These lesions often produce high levels of estrogens, and puberty may progress more rapidly than in a child with central precocity. Girls who are exposed to topical or ingested estrogens or androgens can also show signs of precocity such as breast development or, in the case of androgens, virilization.

Table 7-1 Specific Causes of Precocious Puberty | |

|---|---|

|

Causes of Central Precocious Puberty

Idiopathic

Although this is by far the most common cause of precocity in girls, this is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Cerebral Disorders

These disorders include space-occupying lesions such as congenital malformations (hypothalamic hamartomas), brain tumors (e.g., glioma, astrocytoma, ependymoma, neuroblastoma), neurofibromatosis (optic nerve glioma or hypothalamic glioma), brain abscess, hydrocephalus (sometimes secondary to myelomeningocele), tuberous sclerosis, suprasellar cysts, infiltrative lesions such as sarcoid or other granulomatous disease, sequelae of cellular damage from prior infections (meningitis, encephalitis), head trauma, cerebral edema, or cranial radiation.

Secondary Central Precocious Puberty

Prolonged exposure to sex steroids from any source, resulting in the advancement of skeletal maturation to a bone age of 11 to 13 years, can trigger central precocity. Patients with undertreated or late-treated congenital adrenocortical hyperplasia (CAH) or androgen-secreting tumors may develop early central puberty (28).

Peripheral (Gonadotropin-Independent) Precocious Puberty

Ovarian Tumors

Approximately 60% of ovarian tumors that cause sexual precocity are granulosa cell tumors; the rest are cystadenomas, gonadoblastomas, carcinomas, arrhenoblastomas, lipoid cell tumors, thecomas, and benign ovarian cysts. Ovarian tumors can secrete estrogens and androgens, thus resulting in both breast and pubic hair development.

Adrenal Disorders

Autonomous Follicular Ovarian Cysts

Recurrent ovarian follicular cysts may occur independently but are often associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. Girls with McCune-Albright syndrome have recurrent follicular cysts, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, and large irregular café au lait spots (30,31,32,33,34,35). In these girls, ovarian volumes by ultrasonography are often asymmetric and fluctuate in size over time (32). The mechanism of gonadotropin-independent follicular cyst development in McCune-Albright syndrome is believed to be a dominant somatic mutation in certain cell lines, which results in an overactivity of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate pathway owing to a mutation of the Gsα gene (35). The fluctuating estrogen levels produced by cysts result in sexual development and anovulatory menses.

Gonadotropin-producing Tumors

Tumors that secrete both LH-like substances, such as human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and estrogen (primary ovarian choriocarcinoma) can cause precocious development. The production of LH or HCG alone will cause isosexual precocity in boys but not in girls.

Iatrogenic Disorders

The prolonged use of estrogen-containing creams for labial adhesions may cause transient breast development. Oral estrogen intake (oral contraceptive ingestion) is a rare cause of breast development. It has been speculated that the ingestion of estrogen-like compounds in certain meats or plant foods or environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals may play a role in clusters of cases of premature breast development and in some children adopted internationally who develop precocious puberty (36,37,38).

Primary Hypothyroidism

Ovarian cysts may develop in the presence of severe primary hypothyroidism, perhaps because of cross-reaction of high levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) with ovarian FSH receptors (23,24,25). Premature breast development or vaginal bleeding usually regresses following thyroid hormone replacement. Absence of a statural growth spurt and delayed skeletal maturation accompanying breast development may be a clue to hypothyroidism as a cause of premature development.

Patient Assessment

The initial assessment of the patient with precocious development should include a careful history and physical examination. There is often a history of early pubertal development in relatives of children with idiopathic central puberty between the ages of 6 and 8 years, and timing of puberty in family members should be reviewed. Adopted children with a previous history of poor nutrition may have an increased chance of developing precocious puberty (39). A complete family history must include inherited conditions such as neurofibromatosis or CAH.

On reviewing the child’s own history, the clinician should look for a history suggestive of CNS damage such as birth trauma, encephalitis, meningitis, CNS irradiation, seizures, headaches, visual symptoms, or other neurologic symptoms. Increased appetite, a growth spurt, and emotional lability suggest a significant estrogen effect. The time course of precocious puberty is similar to that of normal puberty, whereas an abrupt and rapid course of development suggests an estrogen-secreting lesion. Abdominal pain, urinary symptoms, or bowel symptoms may be present in patients with abdominal masses.

Vaginal bleeding may be the first sign of precocity in patients with both true precocity and pseudoprecocity. Some children have no signs of puberty but have recurrent menses. This may be a benign, self-limited condition, although this is a diagnosis of exclusion (40,41).

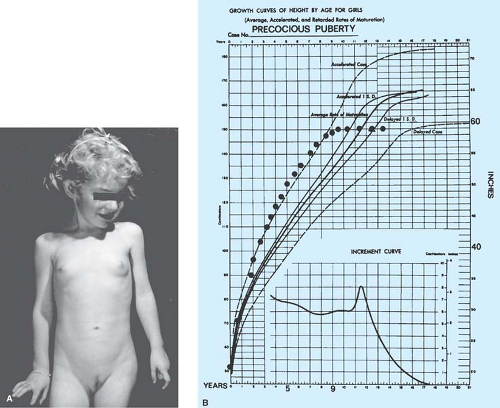

Growth charts should be accurate and up to date, since the growth spurt often correlates with the onset of development in precocious puberty. Girls with idiopathic precocious puberty can show some height acceleration early in childhood years before the onset of secondary sexual development (42). The finding of accelerated growth and advanced skeletal maturation is important in distinguishing between true precocious puberty and premature thelarche. The photograph and growth charts of an untreated patient with idiopathic precocious puberty are shown in Fig. 7-1.

The physical examination should include height and weight measurements. A neurologic assessment, including visualization of the optic discs for evidence of papilledema, should be done. The skin should be assessed for acne, axillary odor, café au lait spots, and pubic or axillary hair. In patients with neurofibromatosis, café au lait spots are multiple brown macules with smooth edges, whereas in those with McCune-Albright syndrome, one or more large macules with irregular borders may be found. The thyroid should be palpated and clinical signs suggestive of severe hypothyroidism (hair and skin changes, low pulse) noted. The breast dimensions and staging of breast development should be recorded. The external genitalia should be examined for evidence of estrogen effect (enlargement of the labia minora, thickening of the vaginal mucosa, and physiologic discharge). This is most easily done with the child lying on her back in the frog-leg position. Signs of virilization such as clitoromegaly, deepening of the voice, increased muscularity, or hirsutism should alert the examiner to the possibility of contrasexual precocity due to endogenous or exogenous androgen excess. The normal prepubertal clitoral glans is 3 mm in diameter. A clitoral glans width >5 mm or an index (clitoral length × width) >35 suggests significant androgen exposure (43). While inspection of the external genitalia is a very important part of the evaluation, a vaginal pelvic examination is not indicated. Ultrasonography of the abdomen is a sensitive tool for assessment of ovarian masses and evaluation of uterine size and shape as an indication of estrogen exposure. Girls with true precocity frequently have mildly enlarged ovaries with multiple small follicular cysts similar to the ovaries seen in the adolescent with a normal age of puberty (44). A single large ovarian cyst may occur in isolation or with McCune-Albright syndrome.

The laboratory evaluation of the child depends on the initial clinical assessment. If the examination clearly shows an estrogen effect on the vaginal mucosa and growth charts reveal an acceleration of linear growth, then more extensive testing is needed. If,

on the other hand, the clinician suspects premature thelarche, the initial tests would be limited to a radiograph of the left hand and wrist for bone age. The radiograph for assessment of skeletal maturation is the single most useful test in the evaluation of the child with premature development. The bone age becomes significantly greater than the chronologic age and the height age in patients with true precocious puberty.

on the other hand, the clinician suspects premature thelarche, the initial tests would be limited to a radiograph of the left hand and wrist for bone age. The radiograph for assessment of skeletal maturation is the single most useful test in the evaluation of the child with premature development. The bone age becomes significantly greater than the chronologic age and the height age in patients with true precocious puberty.

If the vagina shows little estrogen effect and growth rate and bone age are normal, the patient can be monitored by her primary care physician at 3-month intervals to observe whether sexual development progresses or acceleration of linear growth occurs. Not uncommonly, a child has one or several transient episodes of breast budding and growth acceleration that resolve without therapy (45,46). Other children have very slow progression of precocity without rapid skeletal maturation. These children represent the “slowly progressive” variant of early puberty (47). They usually reach adult heights in the normal range without intervention.

If the girl has progressive sexual development, advancing bone age, acceleration of growth, vaginal estrogenization, or the presence of both pubic hair and breast development, then consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist is indicated. In addition to determinations of bone age, initial testing for the evaluation of suspected central precocious puberty usually includes serum levels of LH, FSH, estradiol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and TSH; pelvic ultrasound for assessment of ovarian cysts and size and uterine size and configuration; and MRI of the CNS with contrast medium. Girls with precocious puberty between ages 6 and 8 years with height predictions in the normal range do not necessarily require further testing beyond a bone age. Shorter girls with height predictions in the normal range should be followed with yearly bone ages until at least age 9, however, since height predictions may decline if bone age advances more rapidly than height age.

The interpretation of LH and FSH levels depends on which assay is used. Current commercially available assays include radioimmunoassays (RIAs) and the newer and more sensitive immunoradiometric (IRMA), immunochemiluminometric, and immunofluorometric assays (48

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree