Chapter 28

Postoperative Analgesia

Epidural and Spinal Techniques

Brendan Carvalho MBBCh, FRCA, MDCH, Alexander Butwick MBBS, FRCA, MS

Chapter Outline

NEURAXIAL TECHNIQUES FOR CESAREAN DELIVERY

EFFICACY AND BENEFITS OF NEURAXIAL ANALGESIA

PHARMACOLOGY OF NEURAXIAL OPIOIDS

Distribution and Movement of Opioids within the Central Nervous System

SIDE EFFECTS OF NEURAXIAL OPIOIDS

NEURAXIAL NONOPIOID ANALGESIC ADJUVANTS

The cesarean delivery rate in the United States has steadily increased as a result of changing patterns in obstetric practice,1 and recent data indicate that more than 1 million cesarean deliveries are now performed annually in the United States.2 With cesarean delivery accounting for an ever-increasing proportion of all deliveries in the United States and in many other developed countries,3 strategies for reducing adverse postcesarean maternal outcomes, including postoperative pain, have important clinical and public health implications.

Postoperative pain after cesarean delivery can be moderate to severe and is equivalent to that reported after abdominal hysterectomy.4 Management of postoperative pain is frequently substandard, with 30% to 80% of patients experiencing moderate to severe postoperative pain.5,6 In an effort to improve pain management in the United States, The Joint Commission has stated that postoperative pain should be the “fifth vital sign.”7 The Joint Commission also proposed the goal of having patients experience uniformly low postoperative pain scores of less than 3 (based on a numerical pain scale [0 to 10] at rest and with movement). In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Anaesthetists8 has proposed the following standards for adequate postcesarean analgesia:

A 2007 study suggested that these goals for postcesarean analgesia and maternal satisfaction are frequently not attained.9 A sample of expectant mothers attending birthing classes identified pain during and after cesarean delivery as their most important concern (Table 28-1).10 Effective pain management should be highlighted as an essential element of postoperative care.

TABLE 28-1

Women’s Ranking and Relative Value of Potential Anesthesia Outcomes before Cesarean Delivery*

| Outcome | Rank† | Relative Value‡ |

| Pain during cesarean delivery | 8.4 ± 2.2 | 27 ± 18 |

| Pain after cesarean delivery | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 18 ± 10 |

| Vomiting | 7.8 ± 1.5 | 12 ± 7 |

| Nausea | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 11 ± 7 |

| Cramping | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 10 ± 8 |

| Itching | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 9 ± 8 |

| Shivering | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 6 ± 6 |

| Anxiety | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 5 ± 4 |

| Somnolence | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 3 ± 3 |

| Normal | 1 | 0 |

* Data are mean ± standard deviation.

† Rank = 1 to 10 from the most desirable (1) to the least desirable (10) outcome.

‡ Relative value = dollar value patients would pay to avoid an outcome (e.g., they would pay $27 of a theoretical $100 to avoid pain during cesarean delivery).

From Carvalho B, Cohen SE, Lipman SS, et al. Patient preferences for anesthesia outcomes associated with cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2005; 101:1182-7.

Neuraxial Techniques for Cesarean Delivery

In the United States and the United Kingdom, most cesarean deliveries are performed with neuraxial anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or combined spinal-epidural [CSE] techniques).11–13 A meta-analysis found no differences between spinal and epidural anesthetic techniques with regard to failure rate, additional requests for intraoperative analgesia, need for conversion to general anesthesia, maternal satisfaction, postoperative analgesic requirements, or neonatal outcomes.14 There may be other nonclinical factors that influence the choice of neuraxial anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery. Spinal anesthesia has been shown to be more cost effective than epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery, because needle placement is technically less challenging and adequate surgical anesthesia is achieved more rapidly.15 These advantages, combined with the low incidence of post–dural puncture headache with non-cutting spinal needles (see Chapter 12), have increased the popularity of spinal-based anesthetic techniques for patients undergoing cesarean delivery. A 2008 survey of members of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology found that 85% of elective cesarean deliveries are performed with spinal anesthesia.13 A workforce survey in the United States demonstrated that the majority of laboring women receive epidural analgesia.11 If a patient receiving epidural analgesia during labor subsequently requires a cesarean delivery, most anesthesia providers choose to administer medications through the epidural catheter to achieve adequate surgical anesthesia (see Chapter 26).11–13

A CSE technique incorporates the rapid onset of spinal anesthesia with placement of an epidural catheter for supplementation of intraoperative anesthesia and/or for provision of postoperative analgesia. The CSE technique is increasingly used when prolonged duration of surgery is anticipated (e.g., obesity, multiple previous surgeries).16 After surgery, patients with an epidural catheter in situ may benefit from intermittent bolus injection or continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic and/or opioid for postoperative analgesia.

Efficacy and Benefits of Neuraxial Analgesia

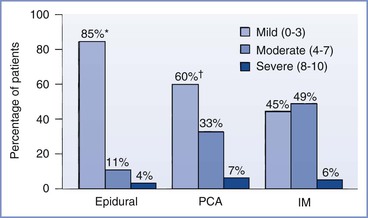

Neuraxial opioid administration currently represents the “gold standard” for providing effective postcesarean analgesia. A meta-analysis of studies involving a broad population of patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures confirmed that opioids delivered by either patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) or continuous epidural infusion (CEI) provide postoperative pain relief that is superior to that provided by intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).17 Similar results have been reported in studies comparing intrathecal and epidural opioid administration with intravenous opioid PCA or intramuscular opioid administration after cesarean delivery (Figure 28-1).18–21 A 2010 systematic review found that neuraxial morphine provides better analgesia than parenteral opioids after cesarean delivery.22 Neuraxial opioids also provide postcesarean analgesia that is superior to that provided by local anesthetic techniques (e.g., transversus abdominis plane blocks) and oral analgesics (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], opioids) (see Chapter 27).23–26 Wound infiltration of a local anesthetic has been proposed as an alternative to an epidural technique for postcesarean analgesia27,28; however, the efficacy and reliability of this technique are variable.29–31 Intrathecal morphine is particularly effective after abdominal surgery.32 Although neuraxial analgesia offers important benefits in optimizing postoperative analgesia, multimodal analgesic strategies should be used to augment the analgesic effect of neuraxial opioids in this setting.25

FIGURE 28-1 Randomized trial of postcesarean analgesia with epidural analgesia, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), or intramuscular (IM) administration of morphine. Percentage of patients reporting mild, moderate, or severe discomfort during a 24-hour study period. *P < .05, epidural versus PCA and IM; †P = NS, PCA versus IM. (From Harrison DM, Sinatra RS, Morgese L, et al. Epidural narcotic and PCA for postcesarean section pain relief. Anesthesiology 1988; 68:454-7.)

Persistent and chronic incisional and pelvic pain have been described after cesarean delivery, with an incidence of 1% to 15%.33–41 Psychosocial and pathophysiologic factors may also increase the likelihood of chronic postoperative pain.42,43 Severe acute postoperative pain is one of the most prominent associated factors.34,37,42,44 The development of chronic pain after surgery has been associated with central sensitization, hyperalgesia, and allodynia. Measures to attenuate or prevent pain sensitization may reduce the likelihood of development of chronic postoperative pain. Studies have shown that the use of perioperative neuraxial blockade may prevent central sensitization and chronic pain.33,45,46 De Kock et al.45 found that intrathecal clonidine, administered before colonic surgery, had antihyperalgesic effects and resulted in less residual pain 6 months after surgery than did placebo. Lavand’homme et al.46 reported that the administration of a multimodal antihyperalgesic regimen (intraoperative intravenous ketamine and epidural analgesia with bupivacaine, sufentanil, and clonidine) was associated with a lower incidence of residual pain 1 year after colonic surgery compared with intravenous analgesia administered during and after surgery. A study investigating risk factors for chronic pain after hysterectomy found that spinal anesthesia was associated with a lower frequency of chronic postoperative pain compared with general anesthesia.47 In another study, persistent postoperative pain was more frequent after cesarean delivery performed with general anesthesia compared with neuraxial anesthesia.34 Additional mechanistic and clinical research is needed to improve our understanding of persistent pain after cesarean delivery and to improve current treatment regimens for managing patients with postcesarean-related pain syndromes.

Although neuraxial opioids provide postcesarean analgesia that is superior to that provided by systemic opioids, some opioid-related side effects (e.g., pruritus) commonly occur after neuraxial opioid administration.18,48,49 Both higher49,50 and lower21,51 maternal satisfaction scores have been reported with neuraxial opioid administration for postcesarean analgesia. This variability in reported maternal satisfaction scores may be influenced by how patients judge analgesic quality against the presence and severity of opioid-related side effects (e.g., pruritus, nausea and vomiting).

Neuraxial anesthetic and analgesic techniques may also confer important physiologic benefits that decrease perioperative complications and improve postoperative outcomes.52–54 The potential benefits include a lower incidence of pulmonary infection and pulmonary embolism, an earlier return of gastrointestinal function, fewer cardiovascular and coagulation disturbances, and a reduction in inflammatory and stress-induced responses to surgery.52–54 In contrast to the wealth of data from clinical studies and meta-analyses that have shown a reduction in postoperative pain with neuraxial analgesia, there is less consistent evidence linking neuraxial anesthesia with a reduction in postoperative morbidity and mortality.52,55

Most patients undergoing cesarean delivery are young, healthy, and at low risk for major perioperative morbidity and mortality. For this patient population, the benefits of neuraxial analgesia include better postoperative analgesia, increased functional ability, earlier ambulation, and earlier return of bowel function.56–59 However, differences in postcesarean complication rates with the use of neuraxial versus systemic opioid analgesia have not been definitively demonstrated.56,60 Surgical trauma and postoperative immobility are associated with an increased risk for postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The risk for venous thromboembolism is 6-fold higher in pregnant women and 10-fold higher in puerperal women than in nonpregnant women of similar age.61 In theory, early ambulation and avoidance of prolonged immobility may reduce the risk for postpartum deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Effective postoperative analgesia can reduce pain on movement, thereby facilitating deep breathing, coughing, and early ambulation. These beneficial effects may lead to a reduction in the incidence of pulmonary complications (i.e., atelectasis, pneumonia) after cesarean delivery.

Neuraxial analgesic techniques may be more likely to reduce perioperative morbidity in high-risk obstetric patients. Women with severe preeclampsia, cardiovascular disease, and morbid obesity may benefit from the reduction in cardiovascular stress and improved pulmonary function associated with effective postcesarean analgesia.62,63 Rawal et al.63 compared the efficacy of intramuscular versus epidural morphine in 30 nonpregnant, morbidly obese patients after abdominal surgery. Patients in the epidural morphine group were more alert, ambulated more quickly, recovered bowel function earlier, and had fewer pulmonary complications.

Investigators have found that CEI of an opioid with a dilute solution of local anesthetic attenuates coagulation abnormalities, hemodynamic fluctuation, and stress hormone responses in nonpregnant patients.64–66 Some studies have suggested that opioid-based PCEA may improve postoperative outcome.67–69 Patients treated with PCEA meperidine after cesarean delivery ambulated more quickly and experienced an earlier return of gastrointestinal function compared with similar patients who received intravenous meperidine PCA.67

Pharmacology of Neuraxial Opioids

Prior to 1974, investigators speculated that the analgesic effect of opioids was due to pain modulation at supraspinal centers or increased activation of descending inhibitory pathways, without a direct effect at the spinal cord. The identification of endogenous opioid peptides, specific opioid binding sites, and opioid receptor subtypes has helped to clarify the site and mechanism of action of opioids within the central nervous system (CNS).70–73 The discovery that opioid receptors are localized within discrete areas in the CNS (laminae I, II, and V of the dorsal horn) suggested that exogenous opioids could be administered neuraxially to produce antinociception. Opioids administered to superficial layers of the dorsal horn produced selective analgesia of prolonged duration without affecting motor function, sympathetic tone, or proprioception.74 In addition, the analgesia provided by intraspinal opioids suggested that many of the unwanted side effects of intraspinal local anesthetic administration could be avoided.75 In 1979, Wang et al.76 published the first report of intraspinal opioid administration in humans. Intrathecal morphine (0.5 to 1 mg) produced complete pain relief for 12 to 24 hours in six of eight patients suffering from intractable cancer pain, with no evidence of sedation, respiratory depression, or impairment of motor function. Subsequently, researchers and clinicians have validated the analgesic efficacy of neuraxial opioids.

Central Nervous System Penetration

Opioids administered epidurally must penetrate the dura, pia, and arachnoid membranes to reach the dorsal horn and activate the spinal opioid receptors. The arachnoid layer is the primary barrier to drug transfer into the spinal cord.77 Movement through this layer is passive and depends on the physicochemical properties of the opioid. Drugs penetrating this arachnoid layer must first move into a lipid bilayer membrane, then traverse the hydrophilic cell itself, and finally partition into the other cell membrane before entering the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Opioid penetration of spinal tissue is proportional to the drug’s lipid solubility. Opioids that are highly lipid soluble (e.g., sufentanil, fentanyl) are unable to cross the hydrophilic cell, whereas those that are hydrophilic have difficulty crossing the lipid membrane.78 Highly lipid-soluble drugs have poor CSF bioavailability because of (1) poor penetration through the arachnoid layer, (2) rapid absorption and sequestration by epidural fat, and (3) high vascular uptake by epidural veins.

Some investigators have questioned the neuraxial specificity of lipophilic opioids given epidurally and have suggested that the primary analgesic effect occurs via vascular uptake, systemic absorption, and redistribution of the drug to supraspinal sites.79–84 Earlier studies suggested that parenteral fentanyl provides analgesia equivalent to that provided by epidural fentanyl.84,85 Investigators postulated that systemic absorption of fentanyl from the epidural space resulted in the subsequent analgesic effect.84,85 Ionescu et al.86 reported that plasma levels of sufentanil were comparable throughout a 3-hour sampling interval after epidural or intravenous injection. In contrast, more recent evidence suggests that epidural fentanyl provides analgesia via a spinal mechanism.87–89 Cohen et al.,90 comparing a continuous infusion of intravenous fentanyl with epidural fentanyl after cesarean delivery, reported improved analgesia and less supplemental analgesic consumption despite lower plasma fentanyl levels with epidural administration. There is evidence that bolus administration of lipophilic opioids has both spinal and supraspinal effects in obstetric patients.87–89 After the administration of an epidural bolus of sufentanil 50 µg,* CSF concentrations of sufentanil were 140 times greater than those found in plasma; however, the amount detected in cisternal CSF was only 5% of that measured in lumbar CSF.91

Hydrophilic morphine has a higher CSF bioavailability, with better penetration into the CSF and less systemic absorption. A bolus dose of epidural morphine 6 mg results in peak plasma concentration of 34 ng/mL at 15 minutes after administration and a peak CSF concentration of approximately 1000 ng/mL at 1 hour.92 A poor correlation between the analgesic effect and plasma levels of morphine has been observed after epidural administration, indicating a predominantly spinal location of action.93,94

Intrathecal administration allows for injection of the drug directly into the CSF. This is a more efficient method of delivering opioid to spinal cord receptors than epidural or parenteral administration. A bolus dose of intrathecal morphine 0.5 mg results in a CSF concentration higher than 10,000 ng/mL, with barely detectable plasma concentrations.95

Distribution and Movement of Opioids within the Central Nervous System

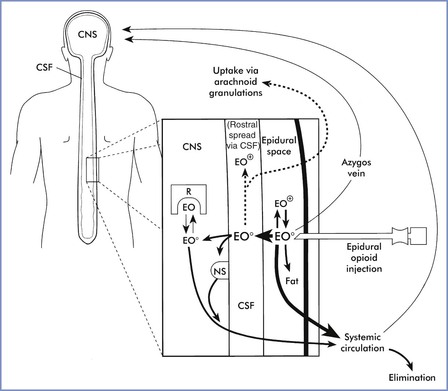

The movement and distribution of opioids within the CNS has been described as follows (Figure 28-2):

1. Movement in the spinal cord (white and gray matter). Lipophilic agents (e.g., fentanyl) are taken up by the white matter with much greater affinity than hydrophilic agents (e.g., morphine), and less drug will reach the dorsal horn in the gray matter.77,78,96

3. Rostral spread in the CSF to the brainstem. Rostral spread is determined by CSF drug bioavailability and the drug concentration gradient; hydrophilic opioids (e.g., morphine) are associated with more rostral spread.91,97

Although opioid dose, volume of injectate, and degree of ionization are important variables, lipid solubility plays the key role in determining the onset of analgesia, the dermatomal spread, and the duration of activity (Table 28-2).80,98 Highly lipid-soluble opioids penetrate the spinal cord more rapidly and have a quicker onset of action than more ionized water-soluble agents. The duration of activity is affected by the rate of clearance of the drug from the sites of activity. Lipid-soluble opioids are rapidly absorbed from the epidural space, whereas hydrophilic agents remain in the CSF and spinal tissues for a longer time (see Figure 28-2).80,98 Sufentanil is more lipid soluble than fentanyl; however, sufentanil has a greater µ-opioid receptor affinity, resulting in a comparatively longer duration of analgesia after neuraxial administration.

FIGURE 28-2 Factors that influence dural penetration, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sequestration, and vascular clearance of epidurally administered opioids. The major portion of epidurally administered opioids (EO) is absorbed by epidural and spinal blood vessels or dissolved into epidural fat. Molecules taken up by the epidural plexus and azygos system may recirculate to supraspinal centers and mediate central opioid effects. A smaller percentage of uncharged opioid molecules (EO0) traverse the dura and enter the CSF. Lipophilic opioids rapidly exit the CSF and penetrate into spinal tissue. As with intrathecal dosing, the majority of these molecules either are trapped within lipid membranes (nonspecific binding sites [NS]) or are rapidly removed by the spinal vasculature. A small fraction of molecules bind to and activate opioid receptors (R). Hydrophilic opioids penetrate pia-arachnoid membranes and spinal tissue slowly. A larger proportion of these molecules remain sequestered in CSF and are slowly transported rostrally. This CSF depot permits gradual spinal uptake, greater dermatomal spread, and a prolonged duration of activity. CNS, central nervous system; EO+, charged epidurally administered opioid molecules. (From Sinatra RS. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of spinal opioids. In Sinatra RS, Hord AH, Ginsberg B, Preble LM, editors. Acute Pain: Mechanisms and Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 1992:106.)

Intrathecal and epidural opioids often produce analgesia of greater intensity than similar doses administered parenterally. The gain in potency is inversely proportional to the lipid solubility of the agent used. Hydrophilic opioids exhibit the greatest gain in potency; the potency ratio for intrathecal to systemic morphine is approximately 1 : 100.98,99

Epidural Opioids

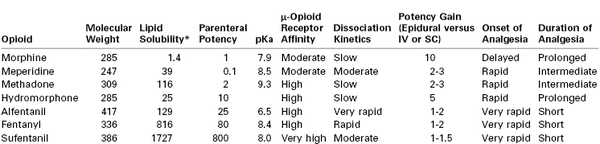

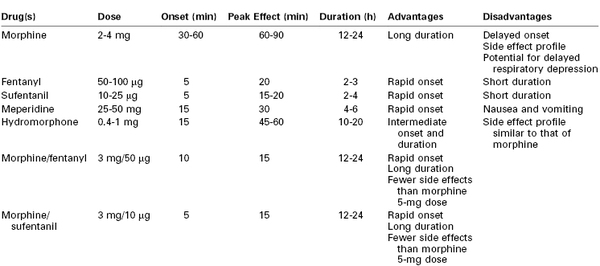

The provision of cesarean delivery anesthesia using an epidural catheter (placed during labor or as part of a CSE technique) has prompted an extensive evaluation of epidural opioids to facilitate postoperative analgesia (Table 28-3).

Morphine

Preservative-free morphine received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for neuraxial administration in 1984, and subsequently epidural morphine administration has been widely investigated and extensively used.100 Epidural administration of morphine provides postcesarean analgesia superior to that provided by intravenous or intramuscular morphine.18–21 A meta-analysis concluded that epidural morphine administration increases the time to first analgesic request, decreases pain scores, and reduces postoperative analgesic requests during the first 24 hours after cesarean delivery compared with systemic opioid administration.22 However, epidural morphine administration is associated with an increased risk for pruritus (relative risk [RR], 2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.1 to 3.6) and nausea (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.3), compared with systemic opioid administration.22

Onset and Duration

After epidural administration, plasma morphine concentrations are similar to those observed after intramuscular injection. Epidural morphine has a relatively slow onset of action, as a result of its low lipid solubility and slower penetration into spinal tissue.80–82,98 The peak analgesic effect is observed 60 to 90 minutes after epidural administration.92 Nonetheless, we prefer to delay epidural morphine administration until immediately after delivery of the infant, or later if maternal hemodynamic instability warrants further delay.

Morphine has a prolonged duration of analgesia, and analgesic efficacy typically persists long after plasma concentrations have declined to subtherapeutic levels.80,92,98 Epidural morphine provides pain relief for approximately 24 hours after cesarean delivery58,101–103; however, there is wide variation in analgesic duration and efficacy among patients. Within the narrow range of doses studied, investigators have not demonstrated a correlation between the dose of morphine and the duration of analgesia.101,103,104

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree