|

conjunction with the impact of the decrease in estrogen after menopause. In this chapter, we review the clinical aspects of postmenopausal hormone therapy, the impact of clinical trial results, and our methods of patient management.

in humans, estrone, estradiol, and estriol, in 1932 at the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization of Sex Hormones in London, although significant amounts of pure estradiol were not isolated until 1936. At this same meeting, the pioneering chemists were bemoaning the problem of scarcity that limited supplies to milligram amounts when a relatively unknown biochemist, A. Girard from France, offered twenty grams of crystalline estrogen derived by the use of a new reagent to treat mare’s urine.7

Composition of Conjugated Estrogens (Premarin) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

prospective cohort study also reported an increased risk of venous thromboembolism with current users of oral therapy, a hazard ratio of 1.7 (CI=1.1-2.8), a ratio that is similar to the usual 2-fold increase repeatedly documented in the literature, and no increase with transdermal estrogen.41 Venous thrombosis is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

increased median levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) by 96% relative to baseline, whereas no change occurred with transdermal estradiol.60 High IGF-1 and low SHBG levels are associated with increased breast cancer risk; however, it is difficult to make clinical conclusions based on these secondary markers. A German case-control study of 3,593 cases found no significantly increased risk of breast cancer with oral or transdermal hormone therapy.61 Thus far, the epidemiologic data comparing oral and transdermal treatment are not sufficient to allow firm conclusions regarding breast cancer risk.

Women at high risk for VTE.

Women with spontaneous or estrogen-induced hypertriglyceridemia.

Obese women with metabolic syndrome.

have been too short (all 1 year or less, except one 2-year study) to determine long-term endometrial safety. Although systemic absorption occurs, the circulating estradiol levels with these low-dose methods remain in the normal postmenopausal range.74,79,83,84,85 and 86 But, because the small increase in circulating estradiol levels causes distant target tissue responses (e.g., an increase in bone density or an improvement in the lipid profile87,88), clinicians cannot assure patients that these methods are totally free of systemic activity. Although the change in blood levels is very slight, and for that reason not effective for the relief of vasomotor symptoms, we believe long-term treatment requires ultrasonographic monitoring of endometrial thickness with biopsy when indicated. This ultrasonographic approach is more preferable than complicating the treatment regimen with the addition of a progestational agent. We further suggest that each patient titrate her dose and schedule of treatment to balance an effective response with minimal dosing. For women who are breast cancer survivors and are considering this treatment, clinicians and patients must accept a small but real unknown risk.

by the cyclic hormonal changes. The addition of a daily dose of a progestin to the daily administration of estrogen allowed the progestin dose to be smaller, provided effective protection against endometrial hyperplasia, and resulted in amenorrhea within 1 year of treatment in 80-90% of patients.99,101,102 and 103

sequential regimen of estrogen and micronized progesterone in contrast to no effect in the group using medroxyprogesterone acetate.117

Progestins Available Worldwide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Because adenocarcinoma has been reported in patients with pelvic endometriosis who are treated with unopposed estrogen,144,145,146,147,148 and 149 the combined estrogen-progestin program is strongly advised in patients with a past history of endometriosis. In addition, we have encountered a case of hydronephrosis secondary to ureteral obstruction caused by endometriosis (with atypia) in a woman on unopposed estrogen for years after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for endometriosis.

Patients who have undergone procedures that have the potential to leave residual endometrium (e.g., a supracervical hysterectomy) should be treated with an estrogen-progestin combination. Responsive endometrium may be sequestered in patients who have undergone endometrial ablation,150,151 and combined estrogen-progestin treatment is recommended for these women.

It has been reported that patients who have had adenocarcinoma of the endometrium can take estrogen without fear of recurrence (discussed later in this chapter), but the combination of estrogen-progestin is recommended in view of the potential protective action of the progestational agent. Treatment can be initiated immediately postoperatively.

The combined estrogen-progestin approach makes sense for patients previously treated for endometrioid tumors of the ovary.152

Comparison Phase III clinical trials are essential. Preclinical studies indicate potential, but only head-to-head comparisons tell us if a new drug is any better than what we already have. The comparison of these agonist-antagonist drugs with tamoxifen is a good example. Hoped-for superiority of the new drugs failed to emerge. In addition, the new drugs will have to perform better than the aromatase inhibitors. Comparison data are also required to determine whether one of the new drugs is superior in avoiding hot flushing and venous thrombosis.

Fracture data for both the hip and spine are necessary. These drugs differ in potency as measured by bone density and biochemical markers of bone metabolism. Greater potency, therefore, gives some hope that one of these new drugs will overcome the serious drawback of raloxifene treatment, a lack of effect in preventing hip fractures.

clinical trial, with a potency comparable to other anti-resorptive agents in postmenopausal women at high risk for fractures.203,204 In a subgroup of women at higher risk for fractures, bazedoxifene had a reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures (50% reduction with 20 mg), compared with both raloxifene and placebo. The only adverse event that differed with treatment was an increase in venous thrombosis with treatment compared with placebo; there was neither a beneficial nor an adverse effect on coronary heart disease or stroke. Treatment for 2 years had no effect on mammographic breast density.205 The results of this trial indicate that the effect of bazedoxifene on bone should be comparable to that of estrogen and bisphosphonates.

|

monkeys.243,244 Although tibolone treatment resulted in lower circulating HDL-cholesterol, coronary artery atherosclerosis extent in monkeys was not significantly different from the control group. Similar results were observed in the carotid arteries.244 That observation prompted the question of whether the HDL-cholesterol reductions noted among the animals treated with tibolone were associated with physiologically meaningful reductions in HDL-cholesterol function. HDL-cholesterol has a critical role in reverse cholesterol transport, the mechanism by which cell cholesterol (i.e., artery wall cholesterol) can be returned through the plasma to the liver for excretion.245 Further, it has been found that cholesterol efflux capacity predicts the severity and extent of coronary artery disease in human patients.246 Postmenopausal monkeys treated with tibolone had no reduction in cholesterol efflux.247 This disassociation between reductions in circulating concentrations of HDLcholesterol and the lack of change in HDL-cholesterol function suggests the likelihood that this may account in large part for the finding that coronary artery atherosclerosis was not increased or decreased in the monkey model.

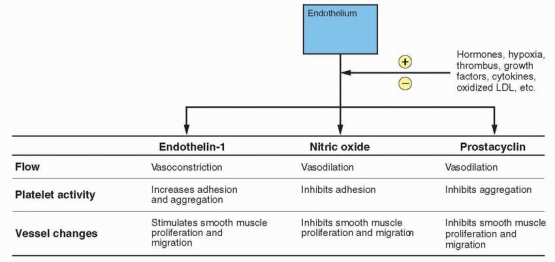

endothelium-dependent responses after tibolone treatment.268 Myocardial infarction and heart failure have been reported to be associated with overactivity of the sympathetic component of the cardiac autonomic nervous system, and tibolone treatment decreases plasma levels of free fatty acids, an effect that results in an improved ratio of cardiac sympathetic tone to parasympathetic tone.269 Another favorable effect connected to tibolone and its metabolites is a direct impact on endothelial cells that results in a beneficial decrease in endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecules, another human finding similar to that in the monkey trial.270

which binds to the progesterone receptor and protects the endometrium from the agonist effects of the two estrogenic metabolites.217,218,219 and 220 This protective effect has been documented in long-term (up to 8 years) human studies.219,220,223,231,232,276,277 and 278 Isolated cases of endometrial proliferation have been reported, for example, 4 of 150 women treated with 2.5 mg daily for 2 years.279 In a 5-year follow-up, 47 of 434 women experienced bleeding, and of these 11 had endometrial polyps or fibroids, but there were two with simple hyperplasia and two with endometrial carcinoma in situ.280 This underscores the standard clinical principle to investigate persistent vaginal bleeding in any postmenopausal woman. In the major U.S. clinical trial, three cases of endometrial cancer were observed, but, in each case, pre-existing carcinoma was later detected when the initial biopsy samples were more extensively examined.253 Nevertheless, a second large 2-year trial was conducted, the THEBES Study, and no endometrial hyperplasia or cancer occurred in the tibolonetreated groups.281

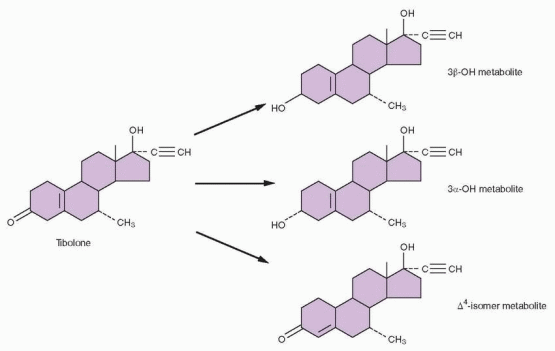

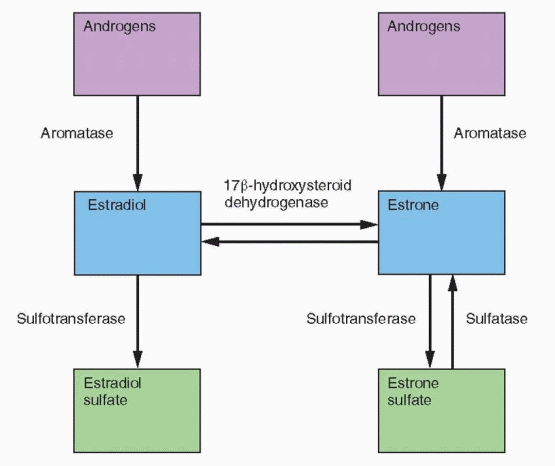

and its 3-hydroxymetabolites increase the conversion of estrone back to estrone sulfate by increasing the activity of sulfotransferase.297 Tibolone and all three metabolites inhibit the conversion of estrone to estradiol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.294 Although these effects resemble progestin activity, tibolone is more potent. Tibolone increases aromatase activity in stromal cells but only at high concentrations that are beyond in vivo levels.295 These tibolone-induced enzyme changes would lower the active estrogen concentrations in breast tissue.

|

the previous 5 years.306 The study was designed to demonstrate that tibolone was superior to placebo, but when the drug monitoring safety board notified the sponsor that there appeared to be an excess of breast cancers in the treated group, the trial was canceled July 31, 2007, 5 months before its scheduled end. The median duration of participation and treatment was about 3 years, with a wide range from a few weeks to almost 5 years. The participants used a variety of adjuvant treatments, mostly tamoxifen, 66.8%; 6.5% used aromatase inhibitors. The dose of tibolone was 2.5 mg daily. Final numbers for analysis were 1,556 women in the treated group and 1,542 in the placebo group. The women ranged in age from under 40 to 79, with a mean age of 52.7 years. 57.8% had positive lymph nodes and 70% had a tumor stage of IIA or higher. Estrogen receptor status was known in 2,808 women in whom the tumors were estrogen receptor positive in 77.8%. In the intent-to-treat analysis, the hazard ratio for recurrent breast cancer in the tibolone-treated women was 1.40 (CI=1.14-1.70). The absolute risk for tibolone was 51 cancers per 1,000 women per year, and 36 in the placebo group. The increase occurred only in women with estrogen receptor-positive tumors. There was no difference in mortality rates between the two groups during the 5-year study period. There were no differences in cardiovascular events or gynecologic cancers, and not surprisingly, vasomotor symptoms, quality of life measures, and bone density improved with tibolone treatment.

estrogenic metabolites acting through the estrogen receptor because it is blocked by an antiestrogen but not by an antiandrogen or an antiprogestin.313 In a large, U.S. dose-response study with doses ranging from 0.3 to 2.5 mg daily, only the 1.25 and 2.5-mg doses produced progressive bone density increases in the femoral neck.253 Indeed, the impact on bone was essentially the same for the 2 highest doses, 1.25 and 2.5 mg. Although the 1.25-mg dose is acceptable for the prevention of bone loss, the 2.5-mg dose is more effective for the alleviation of hot flushes.228 Tibolone prevents the bone loss associated with GnRH agonist treatment (and the side effect of hot flushing).290,314

Women prescribed tibolone in Europe more often had chronic breast disease, a personal history of breast cancer, previous dysfunctional uterine bleeding, hypertension, and previous uterine operations. Most importantly, more women prescribed tibolone had a history of previous treatment with unopposed estrogen. Thus, clinicians were more likely to prescribe tibolone to women they believed were at higher risks for these two cancers, and this would yield higher rates in treated groups compared with control groups.

Drugs For Hot Flushing-Randomized Clinical Trial Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

hormones. Bioidentical hormones are now the focus of a political, financial, and legal conflict. Bruce Patsner, research professor in the Health Law & Policy Institute at the University of Houston Law Center, has written what is, in our view, a masterful analysis of the problem, with suggestions for its resolution.358

Internet-based. The Petition’s major allegation was that these pharmacies were essentially manufacturing new drugs and should be subject to new drug regulations. On January 9, 2008, the FDA announced it would take action against seven pharmacies providing prescription bioidentical hormones, and issued warning letters that potentially could be followed by seizures of drugs and injunctions against production.

clinician because ultimately a prescription is still required. The traditional view of compounding, therefore, is one of personal relationships with patient, clinician, and pharmacists. This becomes a totally different story when a large Internet pharmacy responds to thousands of prescriptions with no knowledge of the patients. What happened to the “individualization” aspect of compounding? Is it practicing medicine by the pharmacy to have a registered clinician employed by the pharmacy to interpret hormone levels and adjust doses?

salivary testing is an appealing idea that has not been addressed scientifically, and given the variability in salivary hormone levels, it is unlikely that clinical studies would yield useful information.

Isoflavones (Genistein, Daidzein, Glycitin) soybeans, lentils, chickpeas (garbanzo beans)

Lignans

flaxseed, cereals, vegetables, fruits

Coumestans

sunflower seeds, bean sprouts

reported in 1999.379,380 Neither demonstrated a significant difference compared with the placebo group. In 1 of the reports, 4 times the recommended dose (4 tablets daily) also had no effect.380 On the other hand, an appropriately designed Dutch study, 2 tablets daily, detected a significant reduction of flushing in a 12-week period of time.381 A large placebo-controlled trial randomized 252 women with severe hot flushing to either Promensil (2 tablets daily) or another red clover extract Rimostil (2 tablets daily for an intake of 57 mg isoflavones).382 The quantitative reduction in flushing (about 41% in 12 weeks) was identical in the Promensil, Rimostil, and placebo groups, although Promensil had a very slightly faster response. In another randomized clinical trial, the effect of red clover (a daily intake of 128 mg isoflavones) on vasomotor symptoms was no better than placebo treatment.383 The best evidence indicates that the impact of red clover on vasomotor symptoms is the same as placebo treatment.

to an increase in bile excretion. The soy peptide binds bile acids and prevents resorption. Alcohol extraction removes the isoflavones from soy protein and causes a loss of the beneficial effect on atherosclerosis in monkeys.411 Thus, both the isoflavone portion and the protein component are required for a full cardiovascular effect. Non-alcohol-washed soy protein extract has been extensively studied in monkeys. This preparation lowers total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol, and raises HDL-cholesterol,412,413 produces coronary artery vasodilation,414 inhibits reduction in coronary flow after collagen induced platelet aggregation and serotonin release,415 and inhibits atherosclerosis but not as robustly as estrogen.408,413

in the spine and femur, with perhaps a modest bone-sparing at the femoral neck with 120 mg/day of isoflavones after adjustment for age and body fat.435 A 1-year clinical trial could detect no impact of soy intake on bone mineral density in either equol producers or nonproducers.436 Flaxseed supplementation had no effect on biomarkers of bone metabolism.437 The difference between hip fracture incidence in Japanese and American women may be due to structural and/or genetic differences not dietary intake.438

Summary of Phytoestrogen Clinical Effects | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

how effective the subsequent protective exposure to a progestin will be.521,522 and 523 It is prudent to assess the endometrium in these patients prior to changing from unopposed to combined therapy. Clinicians should maintain a highly anxious state of mind with patients who have been treated previously with unopposed estrogen.

findings should reduce missed cases of pathology to nearly zero.538 In this circumstance, hysteroscopy is recommended.

of estradiol into the forearm potentiates endothelium-dependent vasodilation, and there is a dose-response effect.580,581 Similar brachial artery dilation has been reported with 0.3 and 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens.582 Comparing brachial artery responses in women who are long-term hormone users (with or without progestin) with nonusers, improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation could be observed with standard doses.583 In careful, randomized studies, the addition of norethindrone acetate or medroxyprogesterone acetate did not reduce the beneficial effect of estrogen on peripheral artery blood flow.584,585 However, not all studies agree; a Danish assessment of brachial artery responses demonstrated no difference between postmenopausal women on long-term combined estrogen-progestin therapy compared with postmenopausal women receiving no treatment.586

|

dose of conjugated estrogens had no effect on hemodynamic responses to treadmill exercise.602 In the monkey, the vasodilatory response to acetylcholine required a blood level of estradiol higher than 60 pg/mL.603 Studies with transdermal estrogen treatment that indicate no effects on endothelial function need to be standardized according to blood levels of estradiol.

unopposed conjugated estrogens to the usual sequential and continuous regimens of conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate, no differences in the treatment groups were observed in the favorable decreases in fasting insulin levels.555 Nonoral administration of estrogen has little effect on insulin metabolism, unless a dose is administered that is equivalent to 1.25 mg conjugated estrogens.625,628 Because a lower oral dose produces a beneficial impact, this suggests that the hepatic first-pass effect is important in this response, at least in normal women; reports with transdermal hormone therapy have indicated improvements in insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, but no effect in women with normal insulin sensitivity.629,630 In double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled studies of postmenopausal women with type 2, noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, estrogen treatment improved all glucose metabolic parameters (including insulin resistance), the lipoprotein profile, and measurements of androgenicity.631,632

fibrinogen, factor VII, and PAI-1 have been observed in premenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women, and oral estrogen alone or combined with a progestin prevents the usual increase in these clotting factors associated with menopause.645,646,647,648 and 649 This would be consistent with increased fibrinolytic activity, a possible cardioprotective mechanism probably mediated, at least partially, by nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Platelet aggregation is also reduced by postmenopausal estrogen treatment, and this response is slightly attenuated by medroxyprogesterone acetate.574 In a randomized 1-year trial, the addition of medroxyprogesterone acetate, either sequentially or continuously, produced a more favorable change in coagulation factors compared with unopposed estrogen.650

The proliferation and migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells in response to growth factors are inhibited by estradiol, and. importantly, this inhibition is not prevented by the presence of progestins.663,664 Nitric oxide, which is regulated by estrogen, also inhibits smooth muscle proliferation and migration.665 Imaging studies have documented a reduction in intimal thickening in postmenopausal women who are estrogen users compared with nonusers, and this beneficial effect is not compromised by the addition of a progestational agent to the treatment regimen.611,666,667 and 668 Thus, postmenopausal hormonal therapy can bring about a reduction in atherosclerosis, and this effect is comparable with that produced by a lipid-lowering drug.666,669

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree