Posterior Compartment Defects

Oz Harmanli

Keisha Jones

DEFINITIONS

Constipation—The following criteria must be present for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis and must include two or more of the following being present during at least 25% of defecations: straining during defecation, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage, manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor), or fewer than three defecations per week. Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives. There are insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

Defecatory dysfunction (DD)—A heterogeneous term used to describe any difficulty with defecation, excluding anal incontinence. DD is often used synonymously with constipation.

Defecatory dyssynergia—A phenomenon whereby the puborectalis and external anal sphincter muscles contract paradoxically during defecation or fail to relax.

Defecography—A dynamic evaluation that provides a twodimensional view to assess defecation in real time, using fluoroscopy. It may identify a rectocele, sigmoidocele, rectal intussusception, and rectal prolapse and can help to exclude pelvic floor dysynergy.

Endopelvic fascia—A network of connective tissue composed of collagen, elastin, and nonvascular smooth muscle strands that connect pelvic support structures.

Incomplete emptying—Complaint that the rectum does not feel empty after defecation.

Midline plication/traditional posterior colporrhaphy—The operation that plicates the posterior vaginal wall fibromuscular layer, usually from the vaginal apex to the perineal body.

Pelvic diaphragm—The muscular support structure, which forms the pelvic floor posteriorly and laterally and includes the levator ani and coccygeus muscles that originate from the pubic and ischial rami at the level of the arcus tendineus levator ani.

Pericervical ring—The location where the endopelvic connective tissue connects to support the structures surrounding the cervix and vaginal apex.

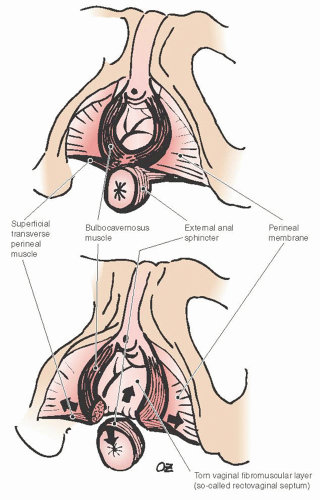

Perineal body—A midline, fibromuscular confluence between the urogenital and anal triangles where perineal membrane and several muscles including the bulbocavernosus and deep and superficial transverse perineal and external anal sphincter muscles are attached.

Perineal descent—A bulge in the perineum where the perineum descends greater than or equal to 2 cm below the ischial tuberosities at rest or with straining.

Perineal membrane—The inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm, which is dense and instrumental in the stability of perineal body and support of the rectum. Some recent anatomic descriptions have begun using the terms, perineal membrane and urogenital diaphragm, interchangeably.

Perineorrhaphy—Reapproximation of torn dense perineal connective tissue including the bulbocavernosus and perineal muscles in an effort to restore the perineal body.

Rectocele and enterocele—The terms used historically to describe protrusion of rectum (rectocele) and other intestines (enterocele) through posterior vaginal wall defects. This is no longer the preferred terminology as the examiner cannot identify the origin of the prolapse accurately with physical examination alone.

Rectovaginal septum (RVS) or fascia—A misnomer for the dense fibromuscular layer of the vaginal wall between the vaginal epithelium and the rectal wall. This structure, which is not a true histologic fascia or septum, is dense distally and becomes adipose with bundles of fibrous tissue and elastic fibers toward the vaginal apex.

Site-specific repair of the posterior vaginal compartment—Identification of the specific defects of the posterior vaginal wall and subsequent repair of these localized defects.

Splinting/digitation—Complaint of need to digitally replace the prolapse or to otherwise apply pressure, for example, to the vagina or perineum (splinting) or to the vagina or rectum (manual evacuation/digitation) to assist voiding or defecation.

Urogenital diaphragm—The fibromuscular structure that spans from one ischiopubic ramus to the other. It is divided in the middle by the genital hiatus, which contains the urethra and the vagina. Urogenital diaphragm includes deep transverse perineal and sphincter urethra muscles and is covered by fascia on both sides like other muscles in the body.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pelvic floor disorders are a prevalent problem that increases cumulatively with age. It is the indication for over 400,000 surgeries annually, representing only a small fraction of those affected by prolapse. The reported prevalence of rectocele varies from 13% to 20% depending on the population studied. Posterior vaginal wall descent is found in approximately 80% of women who have documented prolapse, with isolated rectoceles occurring in 7% of women. Posterior compartment repair is performed in about 40% to 70% of all pelvic floor repairs.

Posterior compartment prolapse can present with symptoms of impaired structure and/or function. Structural abnormalities may manifest as bulge symptoms or sensation of pressure, while functional disorders will usually include defecatory dysfunction (DD). DD is generally used synonymously with constipation, the prevalence of which is estimated as 10% to 15% in most studies and between 9% and 60% in women seen in urogynecology practices. Anal incontinence may also be present but is not typically related to posterior compartment prolapse. The term anorectal dysfunction includes anal incontinence and DD. For the purposes of this chapter; we will focus on DD because anal incontinence is not a typical symptom of posterior compartment prolapse.

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse, the recommended term for bulging that presents in the posterior wall of the vagina, could potentially lead to a protrusion of the anterior wall of the rectum into the vagina (rectocele), small bowel (enterocele), perineal body (perineocele), or the rare entity of the sigmoid colon (sigmoidocele). Bump et al. recommended the term posterior vaginal wall prolapse as the examiner cannot identify with certainty the organs that are protruding through the posterior vaginal wall. This distinction can generally be made once the patient is brought to the operating room.

HISTOLOGY

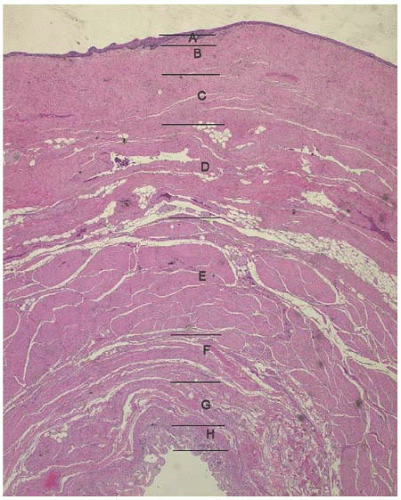

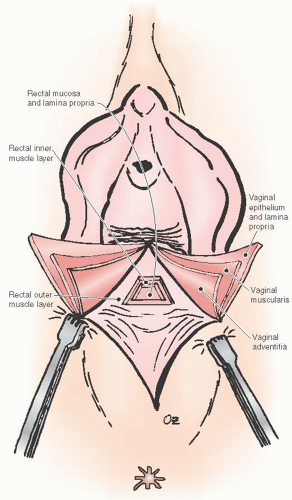

The vaginal wall is comprised of four layers: a nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium; subepithelium, which contains collagen and elastin; lamina propria, a smooth muscle layer; and a loose connective tissue layer, the adventitia. Multiple researchers have investigated the potential alterations that occur in collagen that may result in prolapse; studies have variably concluded that there was overall a lower amount of collagen or a change in the predominant type of collagen in patients with prolapse. In addition, the smooth muscle content of the posterior vaginal wall is disorganized and significantly reduced in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

Histologic studies of the posterior vaginal wall reveal that the rectum with its outer and inner muscular layers, lamina propria and rectal mucosa, lies immediately adjacent to the vaginal adventitia. There is no evidence of a continuous sheet of dense collagen that would qualify histologically as fascia (Figs. 38.1 and 38.2). The layer that supports the vaginal walls is the fibromuscular layer of the vagina, which is rich in elastin. Though technically inaccurate, it has been commonly named “rectovaginal fascia,” “rectovaginal septum,” or “Denonvilliers fascia.” In the proximal vagina, this so-called rectovaginal septum contains mostly adipose tissue, while the most distal 3 to 3.5 cm is dense connective tissue without a true cleavage plane.

ANATOMY

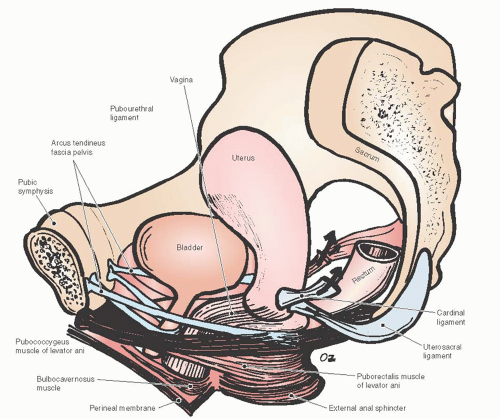

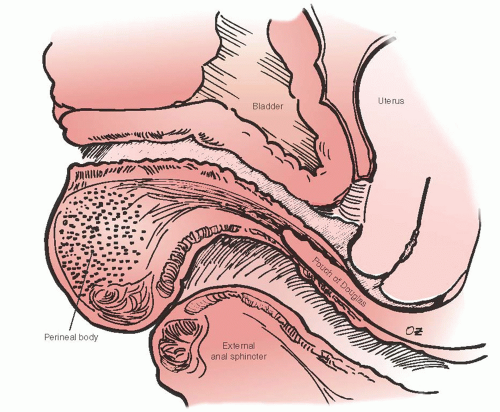

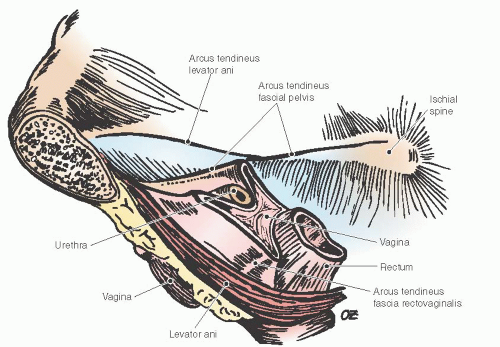

Due to the interdependent nature of the tissues of the pelvic floor, a thorough understanding of the anatomy of posterior vagina is prudent for the gynecologic surgeon planning repair of the posterior compartment. Identification of all anatomic defects is essential when planning surgery for durable outcomes. Pelvic organ support is provided by the vagina, which is supported by the physiologically complex interactions between the levator ani muscles, surrounding fascia, the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, the uterosacral ligaments, the connective tissue attachments of the vagina to the bony pelvis, the perineal body, and the perineal membrane (Fig. 38.3). The network of connective tissue that envelops the pelvic structures including the vagina is known as the endopelvic fascia. Its integrity is critical for pelvic floor support. It is made of collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle fibers. The smooth muscle strands in the endopelvic fascia are long and wavy unlike those that form part of the intestinal and bladder wall. The pelvic diaphragm provides the muscular support and includes the levator ani muscles and coccygeus muscles, which originate at the pubic rami at the level of the arcus tendineus levator ani and create the pelvic floor posteriorly and laterally.

In the presence of normal support, the vagina is pulled posteriorly toward the sacrum by uterosacral ligaments and to a lesser degree cephalad by cardinal ligaments, resulting in an almost horizontal orientation in its proximal two thirds (Fig. 38.4). Damage to any of the apical vaginal support will lead to a more vertical position of the vagina over the levator ani muscles, predisposing to abnormal distribution of pressures to the these muscles, and the subsequent development of prolapse.

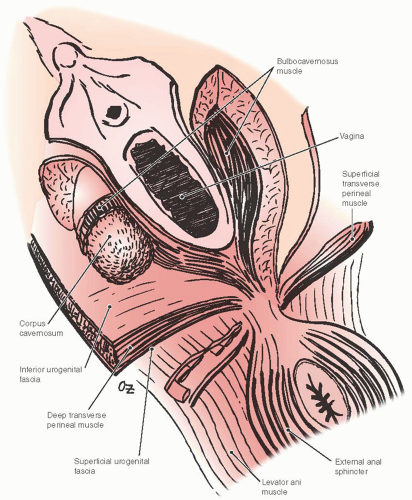

The urogenital diaphragm closes the anterior portion of the pelvic outlet. It spans from one ischiopubic ramus to the other and is divided in the middle by genital hiatus, which contains the urethra and the vagina. The urogenital diaphragm, which includes deep transverse perineal and sphincter urethra muscles, is covered by fascia on both sides similar to other muscles in the body. The fascia on the superior surface is thin and unremarkable, whereas the inferior fascia is dense and deserves a specific name, the perineal membrane (Fig. 38.5).

As described by DeLancey, support of the posterior vaginal wall can also be divided into three levels. The perineal body and its lateral attachments make the most distal level, level III. The perineal body is the key anchoring point where

the perineal membrane and deep transverse perineal muscles attach from each side. There is a debate among anatomists whether deep transverse perineal muscles truly exist because it is difficult to dissect a distinct striated muscle in the dense connective tissue of the urogenital diaphragm, which contains significant amount of smooth muscle fibers as well. The distal rectum lies against the dense connective tissue of the perineal body. The fibers of the perineal membrane contract and resist further displacement when the distal rectum is subjected to increased downward force. The structural integrity of the perineal body is crucial in maintaining resistance to downward displacement as it connects the right and left sides of the perineal membrane. When the perineal body is attenuated, as is often seen following obstetrical trauma, the distal rectum becomes vulnerable to pressure and may prolapse (Fig. 38.6). The bulbocavernosus muscle, which in some anatomic descriptions is referred to as the urethrovaginal sphincter, is a thin, flat muscle with an about 5-mm width that extends dorsally along the lateral vaginal introitus immediately deep to the cephalic edge of the vestibular bulb. Its fibers interdigitate with its counterpart dorsal to the vagina within the perineal body, and as a result, level III support maintains a U configuration. Individual muscles of the perineum are not always easy to identify even in a nulliparous woman. The perineal body is thickest at the distal end of the vagina, but continues as a substantive structure for a distance of approximately 2 to 3 cm cephalad to the hymenal ring (Fig. 38.7).

the perineal membrane and deep transverse perineal muscles attach from each side. There is a debate among anatomists whether deep transverse perineal muscles truly exist because it is difficult to dissect a distinct striated muscle in the dense connective tissue of the urogenital diaphragm, which contains significant amount of smooth muscle fibers as well. The distal rectum lies against the dense connective tissue of the perineal body. The fibers of the perineal membrane contract and resist further displacement when the distal rectum is subjected to increased downward force. The structural integrity of the perineal body is crucial in maintaining resistance to downward displacement as it connects the right and left sides of the perineal membrane. When the perineal body is attenuated, as is often seen following obstetrical trauma, the distal rectum becomes vulnerable to pressure and may prolapse (Fig. 38.6). The bulbocavernosus muscle, which in some anatomic descriptions is referred to as the urethrovaginal sphincter, is a thin, flat muscle with an about 5-mm width that extends dorsally along the lateral vaginal introitus immediately deep to the cephalic edge of the vestibular bulb. Its fibers interdigitate with its counterpart dorsal to the vagina within the perineal body, and as a result, level III support maintains a U configuration. Individual muscles of the perineum are not always easy to identify even in a nulliparous woman. The perineal body is thickest at the distal end of the vagina, but continues as a substantive structure for a distance of approximately 2 to 3 cm cephalad to the hymenal ring (Fig. 38.7).

FIGURE 38.3 Pelvic floor support demonstrating the levator ani muscles and the lateral attachments of the vagina. |

The support of the posterior midvagina (level II) is continuous with the level III support. Level II support is provided by the endopelvic fascia fibers that extend from the superior surface of the pelvic diaphragm on either side of the rectum. Tension generated by these fibers in a dorsal direction creates bilateral posterior vaginal sulci and a W configuration in level II posterior compartment. Together with the levator plate formed by the pubococcygeus component of levator ani muscles, these endopelvic fascia fibers keep the posterior midvagina in a horizontal plane. A rectocele may form if these fibers are detached, as may occur with birth trauma. Any damage to the levator muscles may also result in rectocele by weakening these lateral attachments. Finally, the upper portion of the posterior vagina is attached to the lateral condensations of the endopelvic fascia, namely, the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments or level I support. The final shape of the vagina is determined by the interaction of these three levels of support.

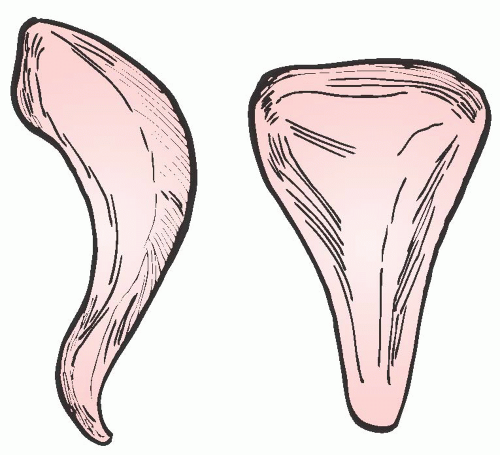

Contrary to the general perception, the vagina is not a cylinder. Level I support makes the vagina wider at its proximal end. The vagina becomes narrower as it extends distally. Its upper two thirds is flattened horizontally due to the intricate balance of the forces controlled by level II support. In addition, the bulbocavernosus muscles practically behave almost as a sphincter at the introitus, making the distal vagina the narrowest portion. Pendergrass and her colleagues demonstrated this well by casting the vaginas of women without pelvic floor defects. Most women were shown to have conicalshaped vaginas with a width of 5 to 6 cm at the apex and 3 cm at the introitus (Fig. 38.8). The average vaginal length is 10 cm with a range from 9 to 12 cm, and it is distensible to approximately 11.5 cm.

Through cadaver studies and clinical analysis, Richardson identified various locations in the posterior vaginal wall where breaks were commonly observed. He concluded that breaks of the fibromuscular network would cause pelvic

organ prolapse (Fig. 38.9). Rectoceles were formed as a result of discrete “rectovaginal fascia” tears at various points along the posterior vagina. His work demonstrated that the most common defect was a transverse separation of the rectovaginal fascia from the perineal body, resulting in a low (distal) rectocele. With similar frequency, he and other researchers identified midline vertical defects that were caused by poorly repaired or healed lacerations or episiotomies. In addition, a high (proximal) rectocele or an enterocele may result from detachment of the vaginal fibromuscular layer from the pericervical ring.

organ prolapse (Fig. 38.9). Rectoceles were formed as a result of discrete “rectovaginal fascia” tears at various points along the posterior vagina. His work demonstrated that the most common defect was a transverse separation of the rectovaginal fascia from the perineal body, resulting in a low (distal) rectocele. With similar frequency, he and other researchers identified midline vertical defects that were caused by poorly repaired or healed lacerations or episiotomies. In addition, a high (proximal) rectocele or an enterocele may result from detachment of the vaginal fibromuscular layer from the pericervical ring.

FIGURE 38.9 The formation of rectocele most likely results from discrete tears occurring in the rectovaginal fascia at various points along the posterior vagina. |

The anatomic findings of Richardson’s work correlate well with the different types of rectoceles encountered in clinical practice. Identification of these defects intraoperatively is paramount for a lasting, successful repair. Defects in midvaginal support can give rise to a rectocele, which may occur in the middle of the vagina despite normal levator function and an intact perineal body. This condition must be addressed not by plicating the rectovaginal fascia but by retrieving and reuniting the separated fibers of the perineal body. If the perineal body has separated from the level II support, they must be reunited.

EVALUATION

History

Pelvic organ prolapse is usually mildly symptomatic or even asymptomatic. It is often discovered by the gynecologists during a routine visit or an encounter for another reason. Prolapse generally becomes symptomatic once it has passed the hymenal ring. Severely symptomatic prolapse usually represents only a small group of patients.

Prior to the first visit, all patients in our practice are sent an intake form for general information including medical history, medications, previous surgeries, obstetrical and gynecologic history, and social history along with standardized condition specific questionnaires. This is reviewed by the physician prior to the patient encounter. Obtaining initial patient data through these forms facilitate the discussion at the first visit as patients with pelvic organ prolapse often have a difficult time discussing some of their symptoms and concerns due to their sensitive nature.

Patients with posterior vaginal wall prolapse usually complain of a sense of pelvic pressure or bulge and difficulty with initiating and completing evacuation. They often report a need

for digitation for bowel movements and pressure on the posterior vagina or perineum in an effort to complete rectal evacuation. Pain during intercourse may also be a consequence of a posterior vaginal wall prolapse.

for digitation for bowel movements and pressure on the posterior vagina or perineum in an effort to complete rectal evacuation. Pain during intercourse may also be a consequence of a posterior vaginal wall prolapse.

Symptoms of DD should be carefully delineated in all women with pelvic organ prolapse, especially in the posterior compartment. When the patient reports constipation, a thorough understanding of stool frequency and consistency is important as the definition of constipation can vary. When evaluating a patient with DD, one must first exclude systemic causes including metabolic, neurologic, endocrine, or psychiatric abnormalities. In addition, if a functional disorder, that is, dysmotility, irritable bowel syndrome, colonic inertia, or functional constipation, is suspected, the appropriate studies should be performed with referral to a gastroenterologist. In cases of obstructed defecation, it is prudent to exclude gastrointestinal abnormalities that could result in these symptoms including rectal prolapse, colorectal tumors, hemorrhoids, or fecal impaction. Defecatory dyssynergia should also be ruled out in patients with a functional abnormality. On defecography or anal manometry, the findings would include contraction or failure to relax the puborectalis and/or the external anal sphincter muscles with attempted defecation. The gynecologic surgeon is then left with a patient with obstructed defecation that is likely due to the anatomical abnormalities associated with posterior compartment prolapse. In many cases, symptoms generally do no correlate with the severity of prolapse. It is not unusual to see a severely symptomatic woman with only mild anatomic defects. A recent cross-sectional study failed to identify an association between symptoms of incomplete evacuation and straining. In addition, the patient should understand that surgery may not improve chronic constipation, and, in fact, constipation may contribute to the return of a rectocele if not managed aggressively after surgery.

Information regarding fecal incontinence, which may present with pelvic organ prolapse, is not always volunteered due to embarrassment. When it is present, the physician must consider appropriate investigation to rule out dysfunction of the anorectal sphincteric mechanism, neurologic abnormality, a bowel lesion, or a rectal mass. Patients may also describe coital discomfort or a sensation of obstruction in the vagina by their partner. This can be due to prolapse in any compartment, but may often be seen when the couple attempts intercourse in the presence of a rectocele and hard stool in the vault. It is important to remember that pelvic organ prolapse is frequently complex; in addition to a careful history of DD, a complete history of any urinary voiding dysfunction should be obtained.

Physical Examination

Physical examination should begin with a brief mental status exam, assessment of cranial nerve integrity, and cerebellar control. Deep tendon reflexes and muscle strength should be assessed in the lower extremities. Once this is complete, the remainder of the exam takes place in a dorsal lithotomy position. Sensory function may be quickly evaluated from dermatomes L2 through S3 by testing for sensation to pinprick or light touch. The integrity of S3 is elicited by swabbing the perineum and observing for a contraction of the external anal sphincter. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse-Quantification exam is performed using a measuring spatula, which can be marked with centimeter markings to improve precision. First, the genital hiatus and perineal body are measured. Then, a lubricated speculum is inserted in the vagina for inspection of the entire vagina and the cervix. At this time, the measuring spatula is placed in the posterior fornix to measure total vagina length when the patient is at rest. The patient is then asked to perform a Valsalva maneuver with the spatula in the vaginal apex to quantify vaginal apical descent. This is followed by inspection and measurement of the descent of each vaginal wall under maximum Valsalva effort when the posterior blade of the split speculum is used to support the opposite compartment.

The examiner should avoid excessive support, especially apically, as this can lead to underestimation of the extent of the prolapse. A bimanual examination is then performed to assess the size and position of the uterus and the adnexa; this can also be used to reassess apical descent as it is of paramount importance in any surgical planning for pelvic organ prolapse. Before the fingers are removed, they are rotated 180 degrees to evaluate the integrity and strength of the levator muscles. The patient is asked to perform a “Kegel” contraction for assessment of the patient’s ability to control these muscles. It is important that the patient believes that the extent of prolapse demonstrated in the office is consistent with what she feels on a regular basis. If the examiner is unable to elicit the maximum extent of her prolapse, the exam should be repeated in a standing position with Valsalva. It may sometimes be helpful to leave the patient alone in the room for her to reproduce a physical activity or position that aggravates the prolapse. If these efforts fail, the exam can be repeated on a different day.

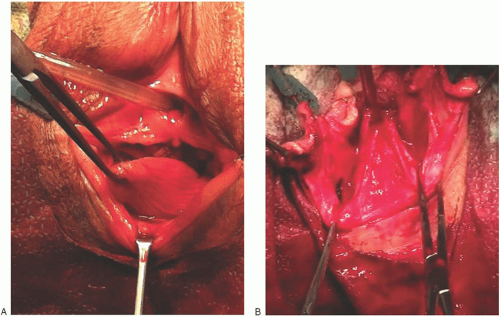

Once the maximum descent of each compartment is ascertained, the focus is turned to delineate exact location of the defects of each compartment. Typically, smoothening and loss of rugae in any part of the posterior wall may indicate an area that lacks fibromuscular support. As reviewed in the anatomy section of this chapter, a common defect seen in the posterior compartment occurs because of separation and retraction of perineal muscles and disruption of so-called rectovaginal septum from the perineal body. This is reflected on physical examination as a finding of skin-fold-like perineal body that has lost its fibromuscular elements including bulbocavernosus muscles in the midline; formation of a dimple between this fold and the most protruding part of the distal posterior vaginal wall; and, commonly, an increased genital hiatus measurement, which often occurs at the expense of perineal body (Fig. 38.10). A longitudinal defect along the rectovaginal fascia, with lateral disruption of the fascia on either side, may present itself as a false and asymmetric longitudinal sulcus. Proximal posterior vaginal wall prolapse, which is a result of an apical detachment of the rectovaginal fascia from the pericervical fascia, also causes loss of rugae and flattening of vaginal surface in the defective area. The perineum is then carefully examined at rest and with straining. If a 2-cm or more descent of the perineum below the ischial tuberosities is identified, there is perineal body descent. A shortened distance between hymenal ring and rectum indicates perineal body deficiency.

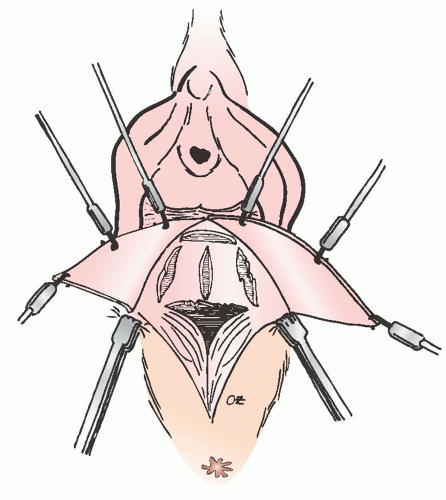

Posterior vaginal wall examination is incomplete until a thorough bimanual rectovaginal examination is performed. Rectal examination begins with inspection of the anus. Then, the examiner inserts one index finger into the rectum first to assess the internal and external anal sphincter tone. Identification of any incidental rectal masses or lesions is crucial. The rectal examination should also include palpation of the rectal wall with simultaneous palpation and observation of the posterior vagina with the other index finger (Fig. 38.11). If the rectal-examining finger contains the entire posterior vaginal bulge, a rectocele is likely present. However, a significant defect above the examining finger likely represents an enterocele or possibly a sigmoidocele.