Polyps and Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Steven H. Erdman and Edward J. Hoffenberg

The most common gastrointestinal tumor in children is the benign single juvenile polyp. Single juvenile polyps are relatively common and do not infer an increased risk of colorectal cancer at any age. In contrast, findings of 5 or more hamartomatous polyps, one or more adenomas, or abnormal dysplastic histology suggest a diagnosis of one of the rare hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. A family history of early cancer or polyps affecting multiple relatives over several generations is also consistent with a hereditary cancer syndrome.

The manifestations or expression of hereditary colorectal cancer/polyposis syndromes can be highly variable within a given family. Most of these syndromes are autosomal dominant, with cancer-related symptoms expected in other family members. The age of presentation, polyp number, and distribution or the age of cancer development can differ among affected family members who carry the same gene mutation. New spontaneous germline mutations are seen in up to one third of newly diagnosed pediatric polyposis patients.

Adenomas are either sessile or pedunculated and can be difficult to differentiate from hamartomas by appearance at endoscopy Adenomas are by definition dysplastic having disorganized epithelial proliferation, loss of goblet cells, cellular and nuclear atypia, and represent the early formative stages of adenocarcinoma. Finding an adenomatous polyp in a child or adolescent suggests the diagnosis of a hereditary adenomatous polyposis syndrome, all of which are associated with a substantial risk of colon or other cancers, so further evaluation and surveillance are mandatory.

BENIGN JUVENILE POLYPS

Juvenile polyps are the most common gastrointestinal tumor during childhood and can be seen in up to 2% of children under the age of 10 years.1,2 These lesions can present with painless rectal bleeding during defecation, or may only present when the polyp prolapses through the anus. Colonic juvenile polyps can also present with colic-like abdominal pain, diarrhea, or unexplained iron deficiency anemia. Juvenile polyps typically present from 2 to 4 years of age but can be found at any time during childhood or adolescence. Most juvenile polyps are solitary and are found in the rectosigmoid colon. Smaller polyps appear as flat sessile mucosal elevations that with time grow into mushroom-like pedunculated lesions. Juvenile or inflammatory polyps are classified as hamartomas. Pathology reveals an overgrowth of mature orderly epithelium with dilated mucus-filled glands, varying numbers of inflammatory cells, and surface ulceration. At times, the inflammation seen in juvenile polyps described as reactive atypia can be indistinguishable from early dysplasia.

HEREDITARY HAMARTOMATOUS POLYPOSIS SYNDROMES

JUVENILE POLYPOSIS SYNDROME

JUVENILE POLYPOSIS SYNDROME

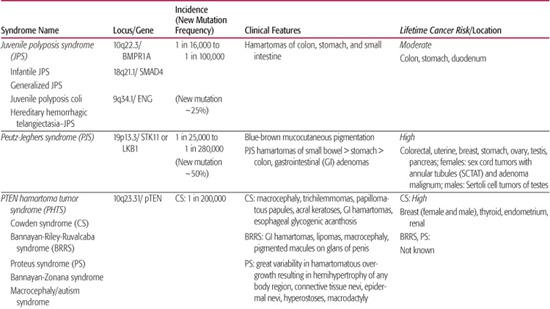

The diagnostic criteria for juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) include: the cumulative development of 5 or more colonic juvenile polyps; the presence of juvenile polyps in the stomach or small intestine (excluding other polyposis syndromes); or the presence of any juvenile polyp with a positive family history of JPS.3,4 JPS is classified as 1 of 4 presentations: JPS of infancy, juvenile polyposis coli, generalized JPS, or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia-JPS (HHT-JPS) (Table 414-1). JPS of infancy is the most severe form of this disease with juvenile polyps forming throughout the digestive tract. Infants present with rectal bleeding, chronic diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, failure to thrive, and decreased survival. Juvenile polyposis coli has polyps limited to the large intestine, whereas those of generalized JPS can be found throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.5,6 HHT-JPS presents with both vascular dysplasias of the respiratory, digestive tracts, brain, and skin, as well as gastrointestinal hamartomas.7

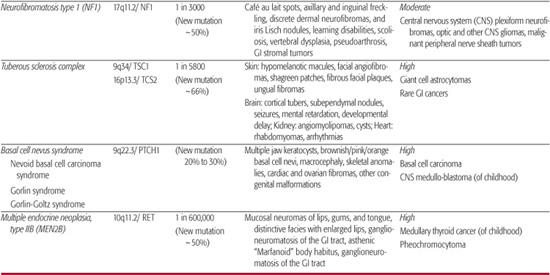

Table 414-1. Inherited Polyposis Syndromes—Hamartomatous Syndromes

JPS has been associated with at least 2 specific genes that involve the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway. Germline mutations or large genomic deletions of SMAD4, BMPR1A, and rarely ENG or PTEN, have been identified in patients with JPS.8,9 Affected, mutation-positive family members can develop polyps from early childhood to late adulthood or not at all. Patients with JPS, either with or without a known genetic mutation, have a cumulative lifetime risk of colorectal cancer approaching 50% beginning in the third decade of life.12,13 These families also show an increased risk of gastric cancer with a risk of pancreatic cancer or duodenal cancer of less than 1%.

Most patients with JPS are identified because of symptoms. At colonoscopic surveillance, all significant polyps should be removed and retrieved for histologic examination. Repeat surveillance colonoscopy with polypectomy should be done yearly until no additional polyps are found, at which time surveillance colonoscopy can be decreased to every 3 years. In some patients, the polyp burden or the presence of dysplastic changes may necessitate the need for subtotal colectomy. For asymptomatic mutation-positive patients, surveillance endoscopy should begin at 15 years of age.12,14

PEUTZ-JEGHERS SYNDROME

PEUTZ-JEGHERS SYNDROME

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (PJS) is characterized by the presence of mucocutaneous macular pigmentation, gastrointestinal polyps, and a dramatically increased lifetime risk of cancer (Table 414-1). The distinctive blue-black macules are most commonly seen at the vermillion border of the lips (95%), buccal mucosa (65% to 85%), and the hands and feet (Fig. 414-1 and eFig. 414.1  ). The classic lesions tend to fade with age, and PJS has been described without mucocutaneous pigmentation. The polyps of PJS are multiple and commonly found in the small intestine (64%), colon (53%), and stomach (49%) (eFig. 414.2

). The classic lesions tend to fade with age, and PJS has been described without mucocutaneous pigmentation. The polyps of PJS are multiple and commonly found in the small intestine (64%), colon (53%), and stomach (49%) (eFig. 414.2  ).6,15 However, polyps can also be found in the nasopharynx, bronchi, and urinary tract. These pedunculated lesions can vary from being diminutive to 5 cm in diameter and can cause gastrointestinal hemorrhage, iron-deficiency anemia, protein-losing enteropathy, or intestinal intussusception.16,17 Although described as hamartomas, the polyps of PJS are histologically distinct from juvenile polyps because of their arborizing abundant smooth muscle extending throughout the polyp toward the surface. PJS is associated with an 11-fold lifetime increased risk for malignancy in multiple organ systems (Table 414-1). During childhood, cancers may develop, including unique ovarian sex cord and testicular Sertolli cell tumors; sexual precocity and male gynecomastia may be the presenting features. Recent studies suggest a cumulative lifetime risk of any cancer exceeding 90% by the age of 65 years.6,18,19

).6,15 However, polyps can also be found in the nasopharynx, bronchi, and urinary tract. These pedunculated lesions can vary from being diminutive to 5 cm in diameter and can cause gastrointestinal hemorrhage, iron-deficiency anemia, protein-losing enteropathy, or intestinal intussusception.16,17 Although described as hamartomas, the polyps of PJS are histologically distinct from juvenile polyps because of their arborizing abundant smooth muscle extending throughout the polyp toward the surface. PJS is associated with an 11-fold lifetime increased risk for malignancy in multiple organ systems (Table 414-1). During childhood, cancers may develop, including unique ovarian sex cord and testicular Sertolli cell tumors; sexual precocity and male gynecomastia may be the presenting features. Recent studies suggest a cumulative lifetime risk of any cancer exceeding 90% by the age of 65 years.6,18,19

PJS management in children focuses on the control of small intestinal and gastric polyps that cause significant morbidity from bleeding, intussusception, and bowel obstruction.20 Recent advances in capsule endoscopy, double balloon enteroscopy, and other imaging techniques offer new diagnostic and therapeutic options (Fig. 414-2). The appropriate role of these newer technologies in the diagnosis and management of PJS in children is not yet certain.

FIGURE 414-1. Macular pigmentation of the lips with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

PTEN HAMARTOMA TUMOR SYNDROME

PTEN HAMARTOMA TUMOR SYNDROME

The PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) encompasses a spectrum of disorders associated with a germline mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene. Inheritance is autosomal dominant with variable penetrance and expression. The disorders include Cowden syndrome (CS), Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS), and Proteus syndrome (PS).6,21 The clinical features of CS, BRRC, and PS are listed in Table 414-1. The gastrointestinal polyps of the PHTS can show marked histologic variation displaying features of adenomatous, hamartomatous, and ganglioneuromatous polyps. CS is associated with an increased lifetime cancer risk; however, the risk for gastrointestinal cancers is not clear.21 Colorectal cancer has been described in an adolescent with CS.22 Guidelines recommend that all CS patients with germline PTEN mutations should undergo surveillance screening. Current diagnostic criteria and surveillance guidelines for CS are available through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Web site (http://www.nccn.org).23

OTHER RARE HAMARTOMATOUS POLYPOSIS SYNDROMES

OTHER RARE HAMARTOMATOUS POLYPOSIS SYNDROMES

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 This disorder, also known as Recklinghausen disease, is associated with neurofibromas of the skin and other organs, cutaneous café au lait spots, and skeletal abnormalities. Patients with neurofibromatosis Type 1 can develop intramural or subserosal neurofibromas, throughout the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery in up to 25% of patients.24 Along with gastrointestinal neurofibromas, inflammatory fibroid polyps or ganglioneuromatosis can also develop resulting in abdominal pain, constipation, protein-losing enteropathy, intussusception, and intestinal obstruction or bleeding. Hormone-secreting duodenal carcinoid tumors, pheochromocytomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and mesenteric arterial vasculopathy are associated lesions and findings.25,26,27

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex This disorder can be associated with hamartomas of the liver, pancreas, and intestinal tract—most commonly the rectosigmoid colon. Colonic papillomas, leiomyomas, adenomas, and adenocarcinomas have also been described in adolescents with tuberous sclerosis complex.28,29

Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome This disorder is known for the development of multiple cutaneous basal cell carcinomas and uncommon development of incidental gastric hamartomas.30,31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree