Pleural Effusions

Angela Lorts

INTRODUCTION

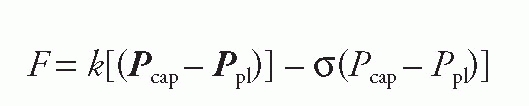

A pleural effusion is an accumulation of fluid between the parietal and visceral pleura. Normally, fluid is produced by the capillaries of the parietal pleura and absorbed by the capillaries of the visceral pleura; only a trivial amount of fluid is left within the pleural space. The Starling relationship governs the net flow of fluid at each capillary bed:

A larger difference between capillary and pleural hydrostatic pressure, or a smaller difference between capillary and pleural oncotic pressure, results in a larger amount of fluid left in the pleural space. Lymphatic drainage normally removes excess fluid from the pleural space. Accumulation of a pleural effusion may result from increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, decreased hydrostatic pressure in the pleural space, decreased capillary oncotic pressure, capillary leak, lymphatic obstruction, movement of fluid from the peritoneal space, or a combination of these factors.

Pleural effusions are classified according to their etiology as transudative or exudative. Pleural fluid analysis can often distinguish a transudate from an exudate and serves as the first step in the differential diagnosis.

Transudative effusions are usually secondary to increased capillary hydrostatic pressure or decreased capillary oncotic pressure. The most common etiology of a transudative effusion is congestive heart failure.

Exudative effusions are typically seen in diseases that injure the capillary membrane, result in increased capillary permeability, or impair lymphatic drainage. A broad differential diagnosis is implied by an exudative effusion and may require more extensive workup.

Transudative Effusion

Cardiac

Congestive heart failure

Increased pulmonary arterial pressure

Superior vena caval obstruction

Constrictive pericarditis

Pulmonary

Acute atelectasis

Hepatic

Cirrhosis

Hypoalbuminemia

Renal

Peritoneal dialysis

Nephrotic syndrome

Iatrogenic

Extravasation from subclavian or jugular central venous lines into the pleural space

Endocrine

Hypothyroidism

Exudative Effusions

Infectious

Bacterial infection (Most common—Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus)

Viral infection (Most common—Adenovirus)

Mycoplasma infection

Fungal infection

Parasitic infection

Neoplastic

Hematologic neoplasm

Cervical teratoma

Pleural mesothelioma

Pheochromocytoma

Wilms tumor

Metastatic sarcoma—Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Bronchogenic carcinoma

Gastrointestinal Disease

Esophageal rupture

Sub-diaphragmatic abscess

Pancreatic pseudocyst

Acute pancreatitis

Intrahepatic abscess

Pulmonary Disease

Pulmonary embolism

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Chronic atelectasis

Hemothorax

Collagen Vascular Disease

Rheumatologic—rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and Wegener granulomatosis

Sjögren syndrome

Lymphatic

Traumatic chylothorax

Obstruction of lymphatic drainage

Congenital lymphangiectasis

Noonan syndrome

Lymphedema

Iatrogenic

Radiation therapy

Surgery

Esophageal sclerotherapy

Extravasation from subclavian or jugular central venous lines

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION

If the etiology of the effusion is unclear, the distinction should be made between a transudate and an exudate by thoracentesis and pleural fluid analysis.

Transudative Effusions

Transudative effusions usually resolve with treatment of the underlying disease process.

Exudative Effusions: Infectious Causes

Parapneumonic Effusions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree