Placenta Previa and Abruption

Helen H. Kay

All bleeding during pregnancy should be investigated by an examination and imaging studies. There are many etiologies for bleeding in pregnancy, but the most clinically significant are placenta previa and placental abruption. These conditions can lead to serious fetal compromise and maternal death. Other causes of bleeding that should be excluded are cervical lesions such as carcinoma or polyps, vaginal lacerations from trauma or carcinoma, other uterine bleeding such as dehiscence of a prior cesarean section scar, and premature cervical dilation, although these usually do not present with large amounts of blood loss. The presence of either placenta previa or placental abruption places the patient in a high-risk situation that warrants close monitoring. A definitive diagnosis is extremely important because in many cases, both commit the patient to a prolonged period of bed rest and hospitalization.

Placenta Previa

Incidence

Placenta previa is encountered in approximately 0.50% to 1.00% of all pregnancies and is fatal in 0.03% of cases. Formerly, the diagnosis of milder degrees of placenta previa without hemorrhage may have gone unnoticed by clinical exam, but now with the widespread use of ultrasound scanning, the incidence appears to be rising. It is more common in multiparous than in nulliparous women, occurring in only 1 in 1,500 nulliparas and in as many as 1 in 20 grand multiparas. The incidence in the United States is declining, probably in part due to the smaller number of grand multiparous women.

Definition

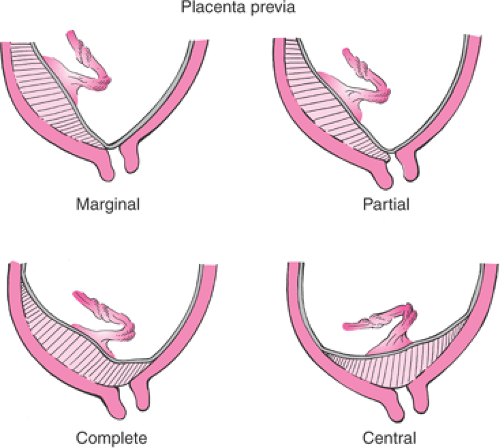

The definition of placenta previa has been complicated because the original descriptions referred to the location of the placenta in relation to a dilated cervix (i.e., in labor) determined by digital exam. By this diagnostic methodology, a complete previa is present when the placenta extends over and beyond the internal os. A partial previa refers to a placenta with its edge partially over the dilated cervix, meaning that if the cervix were visualized with a speculum, placental tissue would be seen over some part of the dilated cervical area but not all. The last type of previa, the marginal previa, refers to a placenta where the edge lies very close to and up to the edge of the os but does not cover any of the dilated cervix. In those original descriptions, the distance between the placental edge and the internal os was never defined in terms of centimeters (Fig. 21.1). However, with the advent of transvaginal ultrasound imaging, the cervix can be routinely imaged, even when not dilated, and the internal os is seen as a point, not a dilated cervix—hence the confusion over the terminology. In today’s practice, any suspected low-lying placenta seen by transabdominal scan should be further evaluated by a transvaginal scan to determine the distance between the edge of the placenta and the internal os (Fig. 21.2). Those cases where the placental edge completely covers the cervical os are labeled as a complete previa. Those with the placental edge at the cervical os should be labeled as partial or marginal (partial/marginal), as it is impossible to determine whether those placentas will remain covered over the dilated cervix during labor or whether they will remain at the edge of the dilated cervix. The cases in which the placental edge is located within 1 to 2 cm of the internal os are the most confusing. Studies that have evaluated the situation where a placental edge

is <1 cm from the cervical os tend to result in cesarean sections because clinically, they are most like those found in placenta previa patients (i.e., with bleeding, and these are delivered by cesarean section). Patients with a placental edge >2 cm from the cervical os are considered to have normal placentas that are not previa. Patients with the placental edge between 1 and 2 cm of the internal os, however, remain in the gray zone. These patients will benefit from either a double setup at the time of labor or close observation in labor and an attempt for a vaginal delivery if there is no bleeding.

is <1 cm from the cervical os tend to result in cesarean sections because clinically, they are most like those found in placenta previa patients (i.e., with bleeding, and these are delivered by cesarean section). Patients with a placental edge >2 cm from the cervical os are considered to have normal placentas that are not previa. Patients with the placental edge between 1 and 2 cm of the internal os, however, remain in the gray zone. These patients will benefit from either a double setup at the time of labor or close observation in labor and an attempt for a vaginal delivery if there is no bleeding.

Pathophysiology

Placenta previa is a condition of abnormal implantation (i.e., into the lower uterine segment rather than the corpus or fundal region). The exact pathophysiology is unknown, but because it is seen more frequently in patients who tend to be older, multiparous, and have had prior cesarean sections or prior uterine curettage, it is thought to result from scarring in the endometrium. This is theorized to lead to abnormal endometrial tissue, poor vascularization, thinner myometrium, and a less favorable location for implantation. Presumably, the embryo is attracted to healthier tissue, which would be the unaffected endometrium of the lower uterine segment. By this rationale, the anterior uterine segment after cesarean section would appear to be an unfavorable site for implantation, but for uncertain reasons, the uterine trauma from cesarean sections actually increases the risk of previa by as much as sixfold.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors have been found that are associated with placenta previa (Table 21.1). The most significant is a prior cesarean section (approximately 1 in 200 deliveries; the incidence is higher if a woman has undergone two or more cesarean sections). Black or minority patients seem to be at higher risk, as are women over 35 years of age. Other risks include increased gravidity and parity and cigarette smoking, with a 2.6- to 4.4-fold increase. Interestingly, meta-analyses have shown a preponderance of male

gender among the fetuses with placenta previa. The mechanism for this is unknown. Previous abortion has not been consistently shown to be associated with an increase in risk for previa.

gender among the fetuses with placenta previa. The mechanism for this is unknown. Previous abortion has not been consistently shown to be associated with an increase in risk for previa.

TABLE 21.1 Risk Factors Associated with Placenta Previa | |

|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of placenta previa can be made by transabdominal ultrasound. With the advent of the curvilinear probe, the cervical and lower uterine segment is much better imaged, and the relationship of the lower placental edge to the internal cervical os can be routinely visualized. However, the most common diagnostic pitfalls include a distended bladder and a lower uterine segment contraction that can lead to misdiagnosis. Of those placenta previas diagnosed in the second trimester, 90% to 95% resolve by the third trimester due to further development of the lower uterine segment, also referred to as “migration” of the placenta. However, if the placenta covers the internal os by 20 mm or more, meaning that it crosses the os by 20 mm, there is a 100% sensitivity rate for detection of previa at delivery, which requires a cesarean section. Three-dimensional scanning may further increase prenatal detection, but this technology remains a new investigational technique for previa at this time. Therefore, it is imperative that follow-up scanning be performed to determine if there is resolution of what appears to be a placenta previa. Marginal and partial placenta previa are significantly less likely to persist into the third trimester (i.e., <5% chance).

Although initially thought to be contraindicated in patients with suspected placenta previa, transvaginal scanning can be performed safely with the appropriate level of caution. In many cases, the relationship between the placental edge and the internal os can be difficult to assess, and only a close-up view with a transvaginal approach can make a definitive diagnosis (Fig. 21.3). This approach to scanning has been studied carefully and does not appear to lead to increased vaginal bleeding, in part because it is technically impossible to introduce the probe through the cervix. Another alternative approach is with translabial scanning, which has been reported to be 100% sensitive for detection of a previa. However, on occasion, bowel gas can interfere. When a clear diagnosis of placenta previa is made by a transabdominal or translabial scan, there is no need to perform a transvaginal scan. However, when a partial/marginal placenta previa or low-lying placenta is suspected, a transvaginal scan should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and measure the distance between the internal os and lower placental edge. Both types of scanning have greatly reduced the false-positive rate by transabdominal scanning alone, which is reported to be as high as 25%.

Figure 21.3 A transvaginal ultrasound image of a complete placenta previa. The arrow points to the internal os. (P, placenta; B, bladder.) |

It is debatable whether transvaginal scanning has made the double setup examination obsolete, because the relationship between the placenta and cervix can be identified well by experienced scanners. However, likely there still is a place for the double setup exam, particularly in those patients who do not experience bleeding and have a placental edge between 1 to 2 cm from the internal os. The double setup can be used in labor to determine the relationship between the placental edge and the cervix by carefully introducing the examining finger into the cervix with the patient prepped and draped in the operating room so that if the placenta is encountered at the internal os, an immediate cesarean section can be performed, particularly when acute hemorrhage is precipitated by the exam. If the cervix is dilated, a finger can be passed through the cervical canal to the internal os, and placental tissue can be palpated as gritty, fibrous tissue in contrast to the fetal membranes that are smooth to the touch, particularly when intact and enclosing amniotic fluid. If placental tissue is palpated that covers the os or is located easily within reach,

it is considered to be a previa. In this circumstance, the distance relationship (i.e., whether it is 1 or 2 cm from the os) is insignificant since that distance is only predictive when determined by ultrasound imaging. At that point, the patient would be managed by proceeding directly with a cesarean delivery. However, if the cervix is dilated, the membranes are ruptured allowing the fetal vertex to be well applied to the cervix, thus any bleeding may be tamponaded by the fetal head, enabling the patient to continue laboring, with or without pitocin augmentation, to achieve a vaginal delivery.

it is considered to be a previa. In this circumstance, the distance relationship (i.e., whether it is 1 or 2 cm from the os) is insignificant since that distance is only predictive when determined by ultrasound imaging. At that point, the patient would be managed by proceeding directly with a cesarean delivery. However, if the cervix is dilated, the membranes are ruptured allowing the fetal vertex to be well applied to the cervix, thus any bleeding may be tamponaded by the fetal head, enabling the patient to continue laboring, with or without pitocin augmentation, to achieve a vaginal delivery.

Clinical Features

Patients with placenta previa typically remain asymptomatic until they have vaginal bleeding. Many are detected during second trimester ultrasound screening, although they remain asymptomatic. It is becoming increasingly rare to have a patient present late in the third trimester with a newly made diagnosis. There are no means to predict which patients will bleed and when they will bleed. Approximately one fourth of patients do not bleed prior to 36 weeks gestation. Usually, the first episode of painless vaginal bleeding occurs without any precipitating event, although intercourse and strenuous physical activity by the patient may be inciting factors. Complete previas are more likely to present with vaginal bleeding earlier than partial or marginal previas. In most cases, the thinning lower uterine segment tears into the intervillous space of the placenta. This bleeding can bring about uterine irritability and, occasionally, preterm contractions. The amount of blood lost in this first bleeding episode tends to be variable, from slight to heavy, although usually it is unlikely to be heavy enough to prompt delivery. However, the amount of subsequent bleeds tends to be increasingly heavier as the cervix and lower uterine segment change as the pregnancy progresses. Blood seen on a patient’s shoes is the classic indication of heavy vaginal bleeding.

Most patients stop bleeding with bed rest, particularly those in the second trimester. Many are placed on bed rest either at home or in the hospital until resolution of the bleeding. The episode of bright red bleeding usually ends as a brownish discharge. However, the amount of bleeding increases in the third trimester, and delivery often is prompted by one massive bleed following multiple earlier lighter bleeding episodes. The blood typically is of maternal origin, and therefore the fetus usually is not in jeopardy. In cases with massive bleeding, however, the fetal heart rate tracing may show signs of distress, usually with repetitive late decelerations.

Patients with placenta previa are at increased risk for placental abruption, cesarean delivery, fetal malpresentation, and postpartum hemorrhage. Although fetal growth restriction formerly was thought to be an outcome of placenta previa, more recent studies do support an association when comparisons are made with a well-matched control group adjusted for gestational age at delivery. Although it is impossible to predict which patients will bleed and when, one report suggests that patients with elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) levels >2.0 multiples of the median (MoM) have a 50% chance of requiring hospitalization for bleeding before 30 weeks gestation, a preterm delivery before 34 weeks, and to be delivered for pregnancy-associated hypertension before 34 weeks. MSAFP elevations did not predict those with placenta accreta or emergent cesarean hysterectomy. Careful note of the MSAFP levels in the second trimester may help in targeting those patients who need to be cautioned more specifically about adverse outcomes in the presence of a placenta previa.

Management

Patients diagnosed in the second trimester should be cautioned about the possibility of experiencing bleeding. Intercourse should be avoided unless a follow-up scan reveals further migration of the placenta. Otherwise, patients may be allowed their usual activities but should avoid strenuous physical exertion. Approximately every 4 weeks, a repeat scan should be performed to determine the persistence or resolution of the previa. If further scans reveal resolution, no further evaluation is necessary. However, if follow-up scans show persistent placenta previa into the third trimester, the patient should be counseled further regarding her chances of bleeding and the need for a cesarean section. Decreased physical activity would be advisable and travel away from home discouraged.

Every patient who bleeds needs to be evaluated and the fetal status documented. Depending on the amount of bleeding, intravenous fluids should be started and blood should be cross matched or, at a minimum, typed and screened. Subsequently, continuous availability of cross-matched blood does not appear to be necessary, as few antepartum patients require emergent transfusion. Rh status should be checked, and RhoGam should be administered if patients are Rh-negative and unsensitized. A baseline blood count with hemoglobin and hematocrit should be determined to assess the degree of bleeding. These blood counts should be interpreted carefully in the context of the normal reserve in pregnancy as well as the hemodilution with intravenous hydration. Because pregnant women have a significant reserve, their vital signs and laboratory values may not directly reflect their vascular compromise until they have had a large amount of bleeding. Their status may be deceptively stable until they approach serious cardiovascular decompensation. If signs of hypovolemia are present, such as hypotension and tachycardia, the patient more than likely has had severe hemorrhage—significantly more than was clinically observed. Since it is rare to develop a coagulopathy with a bleed from a previa, a coagulation profile is not necessary at the onset. A Kleihauer-Betke test for fetal red blood cells in maternal blood also

is not necessary, as it is rare to find an abnormal test result.

is not necessary, as it is rare to find an abnormal test result.

If the fetus clearly is previable, continued monitoring and stabilization of maternal hemodynamics is the appropriate course. Blood can be transfused as needed to maintain the maternal blood count in a normal range (hematocrit >30) until fetal viability is reached. In patients who decline transfusions, erythropoietin may be a good option. In addition, the use of autologous blood donation in these patients may be a safer option in some parts of the world if the blood supply is not routinely tested for infectious disease. If bleeding ceases, the patient may be a candidate for continued outpatient bed rest. Outpatient expectant management has been analyzed, and the cost–benefit ratio has been favorable, with no outcome difference between those managed as outpatients versus those managed as inpatients. Antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity should be administered between 24 and 34 weeks gestation.

In the third trimester, the threshold for discharging the patient should significantly be higher. A period of prolonged bed rest and observation is warranted, and it is not unreasonable to consider hospitalization until delivery. If it appears that immediate delivery is not necessary, patients with intact membranes should be given a course of antenatal steroids from 24 to 34 weeks. Continuous fetal monitoring should be carried out until the bleeding is stable, then daily fetal assessment is appropriate. Additional episodes of bleeding, despite full bed rest, are not uncommon. Approximately 70% of patients treated expectantly will have a second episode of bleeding, and 10% will have a third bleed. Unless acute bleeding mandates an immediate preterm delivery, the patient can undergo semielective amniocentesis after 36 weeks and delivery if fetal lung maturity can be documented. Approximately 25% to 30% of patients will achieve 36 weeks gestation. If significant bleeding occurs after 34 weeks, a decision to proceed directly to delivery without amniocentesis is justified.

In the event of severe hemorrhage on admission, the medical team should prepare for immediate delivery if the fetus has reached a viable gestation. The anesthesiologist and neonatologist should be notified immediately. Two large-bore intravenous lines should be established, and blood should be cross matched promptly. A Foley catheter should be inserted to monitor urine output. A coagulation panel also is warranted. Continuous fetal monitoring should be performed while preparing for delivery and any decompensation should hasten the delivery process.

In about 20% of the women with placenta previa associated with bleeding, the uterus contracts and the additional problem of managing preterm labor needs to be confronted. A transvaginal or translabial ultrasound scan can be performed to assess the status of the cervix if bleeding is not too heavy. If fetal lung maturity is not documented or unlikely, efforts to arrest the labor should be attempted in order to begin a course of antenatal steroids. However, the use of tocolytics is considered controversial, and no studies have confirmed their benefit in these women. The choice of tocolytics should be weighed carefully. β-Mimetics produce maternal tachycardia and hypotension and generally are contraindicated unless the bleeding appears to be stable. Calcium channel blockers can cause hypotension. Indomethacin generally is not recommended after 32 weeks because of possible premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus. Magnesium sulfate is a popular choice and is the most widely used.

Delivery should be by cesarean section for all categories of placenta previa when documented by transvaginal scan with an undilated cervix in the third trimester regardless of whether it is a complete, partial, or marginal previa. However, if the diagnosis cannot be established definitively, such as when vaginal scanning is unavailable, or there is a suspected marginal or partial previa between 1 to 2 cm from the os without any bleeding, a double setup may be considered during or before labor. If no placenta tissue can be palpated, the membranes should be ruptured and the patient may be allowed to labor. Rupturing the membranes and allowing labor to progress could bring the fetal vertex down and tamponade any placental bleeding.

In the majority of cases, a low transverse uterine incision can be achieved, particularly with a posterior placenta and with a well-developed lower uterine segment. A transverse incision can be accomplished in skilled hands even when an anterior placenta is encountered by cutting quickly through the uterus and placenta and delivering the fetus as swiftly as possible before there is significant bleeding and a risk of fetal exsanguination. In a good percentage of cases, the placenta previa causes a fetal malpresentation such as transverse lie. In those cases, the best uterine incision would be a vertical, or classical, one.

Regional anesthesia may be used successfully for patients with placenta previa. It has been reported that the management of blood pressure for hemorrhage is not a problem and may be the preferred choice due to the lowered amounts of intraoperative blood loss compared with general anesthesia. With heavy bleeding preceding delivery, however, many anesthesiologists still opt to use general anesthesia because regional anesthesia in the presence of major hemorrhage may exacerbate hypotension and block the normal sympathetic response to hypovolemia.

Complications

Complications from placenta previa include a longer hospital stay, cesarean delivery, placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, fetal malpresentation, and maternal death from uterine bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Placenta Accreta

Significant complications of placenta previa include placenta accreta, increta, and percreta, particularly with a prior history of a cesarean section. Placenta accreta refers to

the placenta being directly attached to the myometrium, without intervening decidua, but not invading the muscle; increta is noted when the chorionic villi invade the myometrium; and percreta is present when the chorionic villi penetrate through the entire uterine wall and invade into the bladder or rectum. The presence of placenta previa in a patient with a prior cesarean section is associated with accreta in 10% to 35% of cases. With multiple cesarean sections, the risk may be as high as 60% to 65%.

the placenta being directly attached to the myometrium, without intervening decidua, but not invading the muscle; increta is noted when the chorionic villi invade the myometrium; and percreta is present when the chorionic villi penetrate through the entire uterine wall and invade into the bladder or rectum. The presence of placenta previa in a patient with a prior cesarean section is associated with accreta in 10% to 35% of cases. With multiple cesarean sections, the risk may be as high as 60% to 65%.

During antenatal ultrasound scans, the lower uterine segment should be scrutinized for any evidence of a disruption in the demarcation between the placental fibrinoid base known as the Nitabuch layer and the uterine decidua basalis. Color Doppler assessment can be helpful by demonstrating marked or turbulent blood flow within the placenta and extending into the surrounding tissues, which is also described as lacunar flow. Similar, and perhaps better, scrutiny can be offered by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can demonstrate placental tissue extension through the uterus (Fig. 21.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree